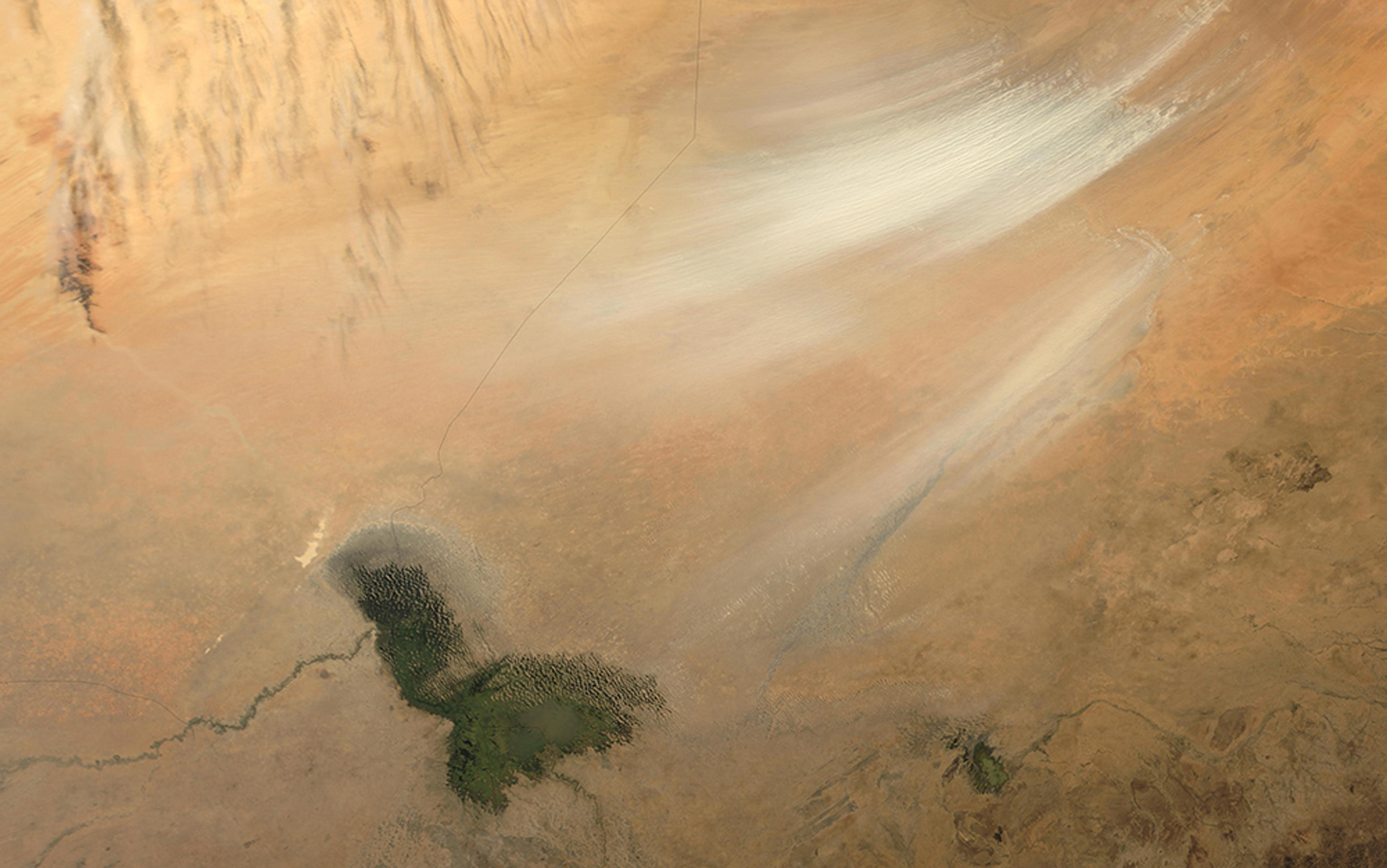

Satellite image depicting desertification in Nigeria/NASA

In June, a deadly heat wave hit Karachi, Pakistan, claiming close to 1,300 lives. As bodies piled outside morgues, and cemeteries ran out of space to bury the dead, the head of the sluggish provincial government, former President Asif Ali Zardari, flew out of the country.

In a city plagued by constant power outages, a seemingly unlikely champion emerged: the Pakistani Taliban (TTP). The TTP issued a clear threat to K-Electric, the private electricity company responsible for the power outages. In Karachi, that usually means a bomb threat.

The TTP is banned, widely reviled, and currently at war with the Pakistani Army in various parts of the country. It is a terrorist group responsible for innumerable attacks on civilians across Pakistan, including the massacre of 145 people, mostly children, at a public school in Peshawar last year.

In this case, a reviled terrorist group was among the first to call out government inefficiency and profiteering in contributing to climate-induced disaster. But all stripes of non-state actors, even murderous ones, have been filling the vacuum created by inadequate public preparedness following climate disasters for quite a while. The interplay of the violent and the political with anthropogenic climate change is no TTP innovation.

In his book Tropic of Chaos (2011), the American investigative journalist Christian Parenti documented how climate change has amplified patterns of violence and poverty. For instance, as drought and flash flooding became exceedingly common in Northern Kenya over the past few decades, paramilitary violence and turf wars over water and cattle accelerated. Famine and devastating El Niño events swept the Karamoja region of Uganda, killing tens of thousands. Survivors took arms to war-ravaged Somalia.

Meanwhile, as the northeastern Brazil – the Nordeste – began to experience extreme drought and flooding, refugees left for the favelas of Rio. Their arrival intensified the already volatile and deadly mix of gang politics, police violence, and the drug trade.

And certainly, over the past decade, as nations quibbled over voluntary accords at Copenhagen and Cancún, the escalating frequency of storms, heat waves, flash floods, drought and desertification had already set off deadly reverberations.

The Syrian Civil War that has so far displaced more than 10 million people and caused a humanitarian refugee crisis of historic proportions is another manifestation of the confluence of war and climate change. A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA in March documented how a drought in the Fertile Crescent from 2007 to 2010 caused farmers to abandon their homes, and flock to Syrian cities. The brutal Assad regime and the 1 million refugees displaced from Iraq fuelled the uprising in 2011 and subsequent civil war together with the various other actors in the region, including ISIS – but the conflict was primed by anthropogenic climate change.

Militant groups and gangs are now vital actors to be reckoned with on a rapidly warming planet, but they are a far cry from the traditionally conceived civil society groups that have historically taken the lead in environmental discourse. NGOs, environmental activists and scientific communities – such as the Greenpeace kayaktivists protesting Shell oil rigs in the Port of Seattle, or the climate scientists on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – have long been singular forces counterbalancing intransigent political leadership, and formed the life force of activism and advocacy for major policy changes such as the Clean Air Act legislation in the US or the Forest Rights Act in India.

Even as a mass grassroots movement has emerged – from the ordinary citizens of Halkidiki, Greece, protesting mining activities that endanger their health and subsistence, to indigenous Iñupiat in Alaska facing relocation due to shrinking sea ice, or ranchers and indigenous tribes using civil disobedience to protest TransCanada’s Keystone XL pipeline – it has by and large been sidestepped by the international political community which has squandered numerous opportunities to institute broad, far-reaching policies to curb carbon emissions.

And as the international community has dithered, the TTP, and other terrorist groups such as Boko Haram and ISIS, have benefitted in its wake.

For instance, in Nigeria, battles between largely Christian farmers and largely Muslim cattle‑herders over land resources has intensified over the past few decades following a crippling series of droughts. Due to drying lakes, Nigeria’s fishing industry has collapsed. Tens of thousands have seen their livelihoods destroyed. Meanwhile, Boko Haram feeds off the ensuing chaos and desperation.

The rising importance of these violent actors speaks to the legacy of profound failure of states to mitigate climate change. An unmistakable pattern has come into focus: as climate-induced crises have begun to accumulate, they contribute to crises of governance where ‘first respondents’ offering some semblance of order, stand to benefit the most. Perhaps, as disorder intensifies in parts of the world already crippled by climate change, it is the aftershocks we should fear the most.