What ‘home’ means isn’t an abstract question in a pandemic. It becomes a concrete matter of where, and with whom, you wish to be confined – if you’re lucky enough to have the choice, that is.

I flew from London to my hometown of Forlì in northern Italy in mid-December. I was 35 weeks pregnant at the time. Despite living and working abroad for 15 years, I felt the pull to return, as I had before the birth of my first child two years ago. The plan was to reap the benefits of the excellent Italian healthcare system, as well as the presence of my extended family, before returning to my university job in the United Kingdom in May.

The Christmas holidays came and went, and in mid-January we welcomed our second son. We paid little attention to reports of the emergence of a novel coronavirus in China. We were occupied with our new arrival, and wanted to believe what the World Health Organization (WHO) was saying about the possibility of containment.

Spring was doing its best to distract us, too. Forlì sits in the centre of Emilia-Romagna, bordering Veneto to the northeast and Lombardy to the northwest. Tucked between the foothills of the Apennines and the Adriatic sea, the farmland around Forlì is the fruit basket of Italy. By late February, the white, pink and fuchsia blooms of cherry, peach and apricot trees had begun to appear, and temperatures had climbed above 20 degrees Celsius. I spent the afternoons watching my two-year-old clamber on play equipment in local parks, chatting to other parents and allowing my little one to soak up some vitamin D.

One morning, I went down to the café below our apartment and ordered an espresso, before settling in to read one of the communal newspapers. Standing shoulder to shoulder with the other patrons at the bancone, I scanned the news about the coronavirus outbreak in Lodi, a town in Lombardy about 260 kilometres from where I was standing. Patient zero was allegedly a 38-year-old man, who’d fallen ill after meeting a friend who’d recently returned from China. Though we were all a bit fidgety about the news, my neighbours were trying to take it lightly. Experts quoted in the newspaper compared the symptoms of COVID-19 – as the disease caused by the virus was now known – to the symptoms of seasonal flu, just a little bit stronger.

In the next 48 hours, the number of cases in Lombardy doubled, and the region recorded its first fatalities. The Italian government closed the borders of the affected towns, and began tracing with whom sick people had been in contact. In the café, the consensus was that the reaction was ‘over the top’. We’re not like China, we said to one another, where people can be locked up in their homes. It was Carnival season; that Sunday, we had a neighbourhood party. Our older son dressed up as King Arthur, with a red mantle and foam sword, and enjoyed throwing streamers and confetti along with dozens of other kids.

Events from the past two months here in Italy now seem like they happened a year ago. What was so recently inconceivable has become the norm in societies around the world. At the time of writing, schools, universities, museums, libraries, theatres, cinemas and gyms are all closed; parks and playgrounds are cordoned off (and patrolled by drones); all businesses and restaurants have been shut down except for grocery stores, pharmacies and some essential factory production lines; walks and runs for leisure, even alone, are banned; gatherings of any size, in public or private, are prohibited. You need to fill out a form to self-certify why you are going outside. Policemen patrol the streets. Benches in the local square are roped off, to deter people from sitting in the warm sun and leaving traces of a virus that we now know can survive for days on certain surfaces.

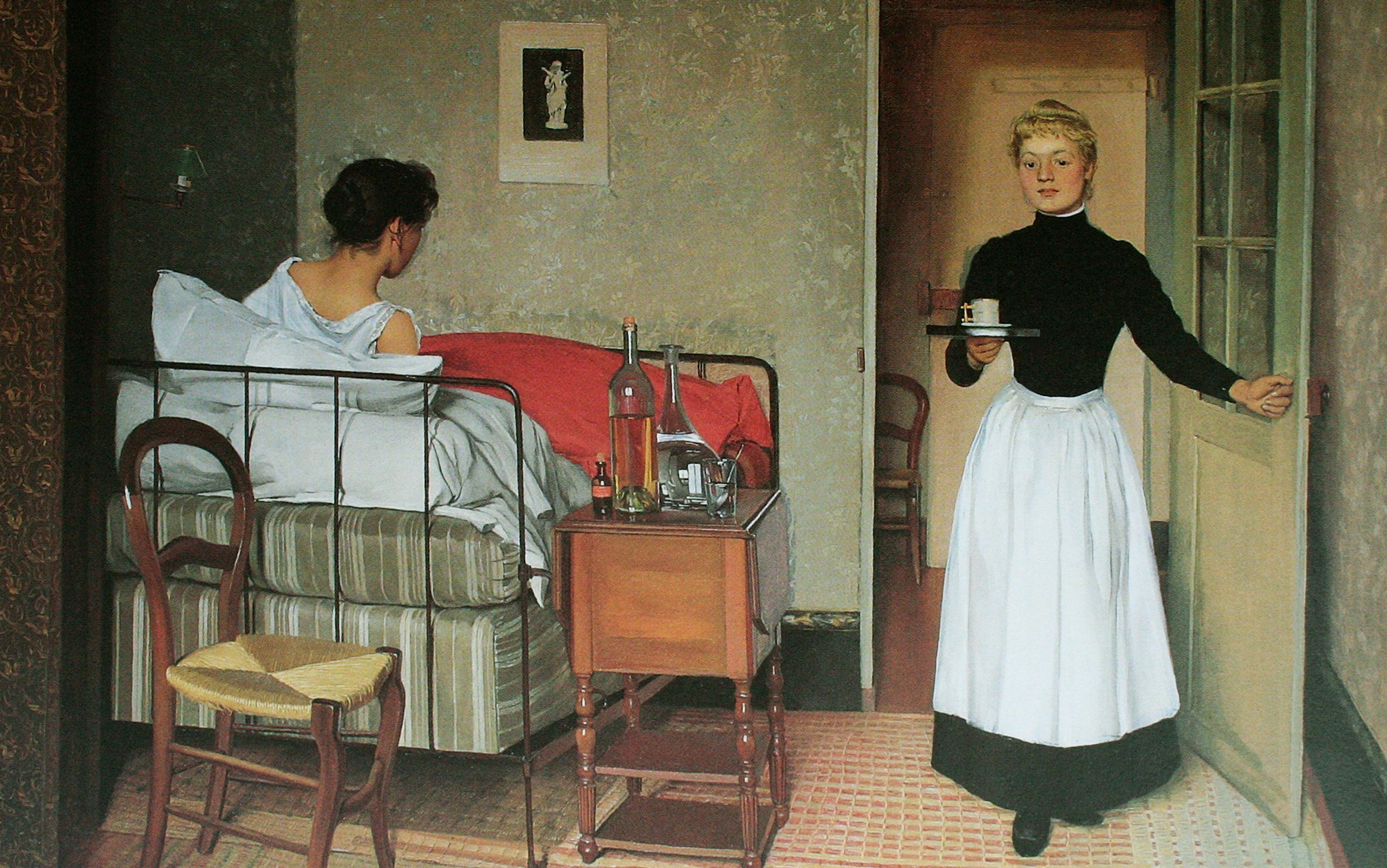

As a bioethicist, I can’t help but reflect on the situation with my professional hat on. A major ethical issue during the Italian crisis has been the fact that doctors have been thrust into a position of responsibility for allocating healthcare resources under conditions of dramatic and unexpected scarcity. After the Lodi outbreak, hospitals in Lombardy quickly reached capacity, with beds laid out in camp-like conditions, and with an insufficient number of respirators and ventilators for all the patients who required them. The Italian College of Anaesthesia, Analgesia, Resuscitation and Intensive Care tried to make the decision criteria for access to intensive care transparent, to relieve some of the pressure placed on doctors. The document they released in early March aimed to guarantee ventilators for patients with the highest probability of therapeutic success – that is, those with the ‘highest hope of survival’. The criteria adopted were utilitarian: age and pre-existing medical conditions were factors that pushed a patient down the line.

Our privilege has concealed the reality of finite healthcare resources

The document provoked an uproar. The media feasted on it, spreading the panic. The situation in Italy was certainly exceptional due to the sheer number of cases presenting themselves each day. It’s likely the first time that many of these doctors, especially the younger ones, were being faced with such harrowing choices. Yet, from an ethical point of view, the document was neither unprecedented nor revolutionary. In another context of scarce resources – organ donation – patients are routinely ranked on waiting lists using an algorithm. Standard criteria match donor organs to recipients using a calculation of the chances of the transplant’s success and the patient’s survival. More controversial criteria can apply too. For example, if someone has cirrhosis of the liver caused by drinking, their personal responsibility in causing the condition will, in some circumstances, be a factor that weighs against their receiving a transplant.

There’s no escaping such dilemmas in our healthcare system, which will always have finite capacity. As bioethicists, we are trained to think about how to develop appropriate criteria, to ask what fairness requires, and to reflect on what features, if any, make a particular case similar or dissimilar to another. In the current situation, there’s admittedly a striking difference between allocating the scarce resource of an organ and the use of scarce ventilators: while patients can live for years on dialysis if their kidneys are failing and they need a transplant, many people with serious COVID-19 symptoms will die imminently if they can’t breathe. This distinction is what makes it so difficult for physicians, and so difficult for the public to accept that, nonetheless, such decisions must be made. However, there’s nothing intrinsically appalling about the use of criteria – indeed, it’s appropriate and even comforting to know that doctors are accountable to objective standards when deciding who should be at the front of the queue for treatment.

The fact that we Italians think that these decisions are exceptional reveals the ways that our privilege has concealed the reality of finite healthcare resources. One of my bioethics students, Caitlin Gardiner, is also an Accident and Emergency (A&E) doctor in the UK. She reminded me that, in her native South Africa, such balancing acts are the norm. There, as she told me, only the tiniest fraction of patients who are ‘not too sick’ – that is, not too old, not living with HIV/AIDS, not too ill or too premature, if they’re babies – get to receive intensive care. And death from tuberculosis (another infectious respiratory disease), after being denied access to intensive care, is entirely normal. There are lessons to be learnt from the Global South, such as how to have humane but open discussions about prioritising patients. It’s best to have this kind of conversation in a non-emergency situation, when the emotions of patients, relatives and clinicians aren’t running quite so high. Arguably, we should talk not just about whom to intubate, but also about when to withdraw ventilation if a patient with a better chance of survival were to arrive. Beyond the context of a pandemic, developed countries don’t typically face these quandaries, which explains the moral distress on the COVID-19 wards in northern Italy, where doctors and nurses have been reported weeping in the hallways.

My last social engagement was a dinner on a Saturday evening in early March, at the home of one of my oldest friends. I’ve known this particular group of women since we were children playing ballgames together in the street, as the shadows lengthened during the long summer afternoons. However, the congenial mood that night was spoiled by news leaked to ANSA – the Italian equivalent of Reuters – that more draconian lockdown measures were to follow the next day. Parts of Lombardy, Emilia-Romagna and Veneto had been under various restrictions for the past fortnight, but now we learnt, chillingly, that people would be prevented from entering or leaving the worst affected regions – a move that seemed unprecedented and surreal in a democratic state such as Italy. While Forlì had been spared for the moment, we knew it was only a matter of time before we, too, would acquire ‘red status’, and have restrictions placed on our movements. We said goodbye, not knowing when we’d see each other again. Forlì registered its first case of COVID-19 that weekend; by Tuesday, the whole country was in lockdown.

The crisis has revealed fresh aspects of the Italian national character. It’s particularly interesting that the epicentre of the outbreak is in the north, striking those regions that stereotypes hold to be hardworking and industrious. In a turning of the tables, the south of Italy can finally blame the north for its problems – quite literally, as people rushed to take the last trains heading south from Milan, Bologna and Turin on the Saturday of the lockdown, spreading the virus as they went. Historically, it has been the opposite, with northern Italians blaming southerners for wasting the resources accumulated by their labour.

The abandonment of this greeting is nothing less than the unlearning of a lifelong, embodied instinct

Italy is not a particularly patriotic place – at least, not until now. My American husband was surprised, on his first trip, to note that we Italians don’t tend to hang flags from our homes or apartments, and almost never sing the national anthem (except at the football World Cup and, even then, we don’t know the words). Now, for the first time in my life, I routinely see Italian flags sprouting from windows, sometimes accompanied by a European flag, sometimes by the red-and-white crest of the city of Forlì. People are singing the national anthem, as well as arias from Verdi or Puccini operas, from their balconies. Perhaps, most miraculously, we Italians have finally learnt how to wait in line (and a spaced one, at that).

But social distancing also comes at the cost of certain national habits. Handshakes and kisses as a way of greeting have become taboo. The abandonment of this traditional greeting is no minor thing; for an Italian, it’s nothing less than the unlearning of a lifelong, embodied instinct, something that goes to the heart of Italian sociality. First impressions might be misleading, but my grandmother taught me never to trust someone with a weak handshake.

I’ve been wondering what my grandmother would say about COVID-19, if she were still alive. Although she didn’t experience the H1N1 influenza pandemic (or Spanish flu) of 1918-19, she grew up in its aftermath; it’s estimated that at least 30,000 people died in Emilia-Romagna alone. My grandmother took an active role in raising her grandchildren, as do many grandparents in Italy today. One of the saddest features of the pandemic is the rift it’s created between the generations, as grandchildren have become potential vectors for the disease to infect the elderly and vulnerable.

My American in-laws flew over to Italy to meet their second grandchild just a couple of weeks before the lockdown began. When we picked them up from the airport in Bologna, we joked and riffed on the lyrics from ‘Hotel California’, saying that they might check out of Italy, but they’d never be able to leave. Soon it became a reality: their flight home was cancelled, and they went back and forth about whether to return at all. We worked through the scenarios, considering the various possible familial distributions of health and illness, togetherness and separation. In the end, my in-laws decided to go home earlier than planned, for reasons similar to those that had drawn me back to Forlì before each of my sons was born. When imagining oneself vulnerable, one wants to be surrounded by familiar people and places.

This act of separation made me reflect on the intergenerational ethics of how countries have responded to the crisis. COVID-19 appears to be relatively mild in children, according to the data available so far, while the more serious and life-threatening symptoms cluster disproportionately (though not exclusively) among older people, and those with underlying conditions. This sets it apart from the Spanish flu pandemic, in which both young children (under five years old) and people over 65 were among the worst affected. Even more unusually, the Spanish flu also struck down people between the ages of 20 and 30 years old, predominantly men, for reasons we don’t fully understand. However, the current lockdown measures treat everyone the same way. Some countries, including the UK at the beginning of the outbreak, proposed policies that focused on isolating the vulnerable, however these have largely been abandoned in favour of blanket prohibitions. In my own town, police vans patrol the streets with megaphones, reminding me of the dystopian future that I never dreamed I would live in.

There’s no such thing as a value-free model – the longterm effects of lockdowns must be accounted for

When confronted with epidemiologists’ models showing that particular measures will save X number of lives, it’s hard for politicians not to implement them – especially if other countries are already doing so. Saving lives in the short term by shielding the healthcare system and flattening the curve of infections is obviously a vital goal. However, it cannot be the only one. The social lockdown has very real economic and mental health repercussions for large sections of the population. The damage and deaths it causes will be more difficult to quantify than those directly caused by COVID-19, but they will still exist. As the Italian statistician Maurizio Bettiga has argued, this isn’t just a scientific question, but also a moral one about which values we should prioritise.

There’s no such thing as a value-free model. Self-isolation and quarantine are much heavier physical and mental burdens for those who live alone. John Ioannidis, the professor of medicine at Stanford University who exposed the ‘replication crisis’ in social psychology and beyond, has argued since the beginning of the pandemic that the economic, social and mental health implications of lockdowns must be accounted for in cost-benefit public health calculations – including the deaths caused by disruption to the social fabric. We might end up looking back on coronavirus, Ioannidis said, as a ‘a once-in-a-century evidence fiasco’. There’s currently little evidence that the most aggressive measures work, and if they continue, they could end up causing more harm in the long term than riding an acute epidemic wave. However, discounting the future is a typically human bias – as health economists know well from studies of how people think about the consequences of smoking, drinking or failing to exercise.

In the absence of robust data, blanket policies could be justified with resort to the ‘precautionary principle’ that it’s better to be safe than sorry. This could also be the basis for continuing the lockdown for an extended period of time. But even with these caveats, a lockdown policy isn’t the only solution to the outbreak. Sweden has experimented with limiting freedoms for only the most at-risk segments of the population, and has kept schools, bars and restaurants open. Research carried out at University College London has shown that the benefits of closing down schools are very limited when compared with the longterm economic and social costs. Rather than limiting free movement, one approach aims to reduce travel at certain times of the day only, by creating a timetable for staggered opening hours and work shifts, to avoid crowding on public transportation. This policy was used with some success in New York City during the Spanish flu.

These policies rely on the available (although partial) data that show that particular, identifiable groups are most vulnerable to the disease. They’re also based on a ‘principle of proportionality’, by which the severity of restrictions should be consonant with the likelihood and gravity of the risks they’re offsetting – especially if the measures will be in place for a while. This principle is one of the core ethical standards that guide the management of emerging infectious disorders, as set out by the WHO, the Nuffield Council on Bioethics in the UK, and by the German Ethics Council. My three younger brothers, all in their 20s, have little reason to be scared about COVID-19 from the perspective of their own health; on the basis of the available evidence, the infection fatality ratio (the percentage of infected people who die) is directly correlated with age, and mortality in the 20-29-year-old category is 0.1 per cent in Italy, at the time of writing. That doesn’t mean that people under 30 can’t die of COVID-19, but that it’s extremely unlikely.

After asking younger people to do so much, perhaps we ought to give them something in return

Younger generations have been asked to make huge sacrifices for older generations, with the expectation of only very limited benefits for their own health – and some big repercussions for their own physical and mental wellbeing, including the closure of universities and loss of opportunities to work. This is also the generation that will have to pay off the bulk of debts we’re now accruing to pay for government assistance packages. Beyond family ties, the moral basis for this request isn’t obvious. On the one hand, we’ve asked a lot from younger people, without really making the case for those policies. On the other hand, when younger generations make demands of older generations – for example, about climate change and the future health of the planet – older people in power seem to have a hard time accepting them. After asking younger people to do so much for the elderly during this crisis, perhaps we ought to give them something in return.

The ethics of how to prioritise certain lives over others, and on what basis, go beyond finding justifiable criteria for how to allocate scarce healthcare resources. One of the very tangible, if under-recognised, repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic is the near-total shutdown of the clinical trial industry, as hospitals near capacity and labs mobilise to find and fast-track new drugs to inoculate and treat COVID-19. For people with other life-threatening conditions, who have exhausted their treatment options, the shutdown of the clinical trial industry is a disaster. Entering into a trial for an ‘experimental’ or ‘investigational’ drug might be their best chance of leading a bearable life – or of having any life at all. A friend of mine in the United States, who has metastatic Stage 4 breast cancer, has been on a trial for more than a year already. Now the pandemic has made it impossible for her to visit the research hospital where the trial is taking place, because she would be too vulnerable to experiencing severe symptoms if she contracts COVID-19.

Another ‘victim’ of the crisis is the delay or cancellation of routine child immunisation programmes in countries around the world, as governments try to stop the spread of the disease. As a mother of an infant, I want my child to be vaccinated against measles, rubella, polio and the plethora of infectious diseases that pose a tangible threat to a newborn. There might be justifications for prioritising people suffering from COVID-19, however as a society we at least need to have an honest conversation about the human price we’re paying for that care.

At the time of writing, these are the things I can do: go to the pharmacy or the shop for groceries, provided I go alone and wear a mask (masks are now compulsory when going out in Forlì); take my children for a walk within the vicinity of home; and walk a dog, if I had one. I cannot go out for a run, my preferred form or exercise – this was banned among increasing social and social-media pressure to do so. A friend who lives alone in Milan, and is also a runner, told me that people had started yelling insults at her from their balconies even before the ban came into place; more worrying still, news reports are emerging of attacks on joggers around the world.

Neighbours have become invigilators, taking it upon themselves to enact the law. People are looking for an untore (a spreader) – a scapegoat, somebody to blame – as they’ve done in previous pandemics. The 19th-century Italian writer Alessandro Manzoni explored the phenomenon in his novel The Betrothed (1827), set during an outbreak of the plague in Lombardy in 1630; the mob believes that some young Frenchmen, found to be touching a screen and pews inside the cathedral of Milan, were deliberately spreading the disease, and they turn violent and suspicious toward all foreigners.

When I’ve discussed the ban on running with my friends, looking for sympathetic outrage, I’ve been surprised to find that several of them agree with it. On what basis? I ask. There’s no scientific foundation for the claim that people spread this virus by simply going for a run or walk. Isn’t that an unjustified restriction of people’s basic freedom? According to most public health and ethics scholars, it would be. Having access to the outdoors helps relieve pressure in a situation that’s extremely psychologically taxing, and public health policies should take into account the implications of the lockdown on their citizens’ mental health. However, my friends had remarkably similar answers: we stay home out of respect for the doctors and nurses on the frontline; we are all in this together; we are sacrificing our individual freedom for the public good; we need to show respect. To go running or walking outside shows a lack of respect, they say.

I remain unconvinced. Most countries allow (or encourage) at least a daily run or walk while under lockdown. From the point of view of public health, the Italian ban falls far short of the criterion of proportionality, and lacks the evidentiary basis for a public health intervention in the context of an outbreak of an infectious disease. All in all, am I going for a run? I am not. Not because I agree with the prohibition, but because the experience would be ruined, knowing that someone could report me to the police.

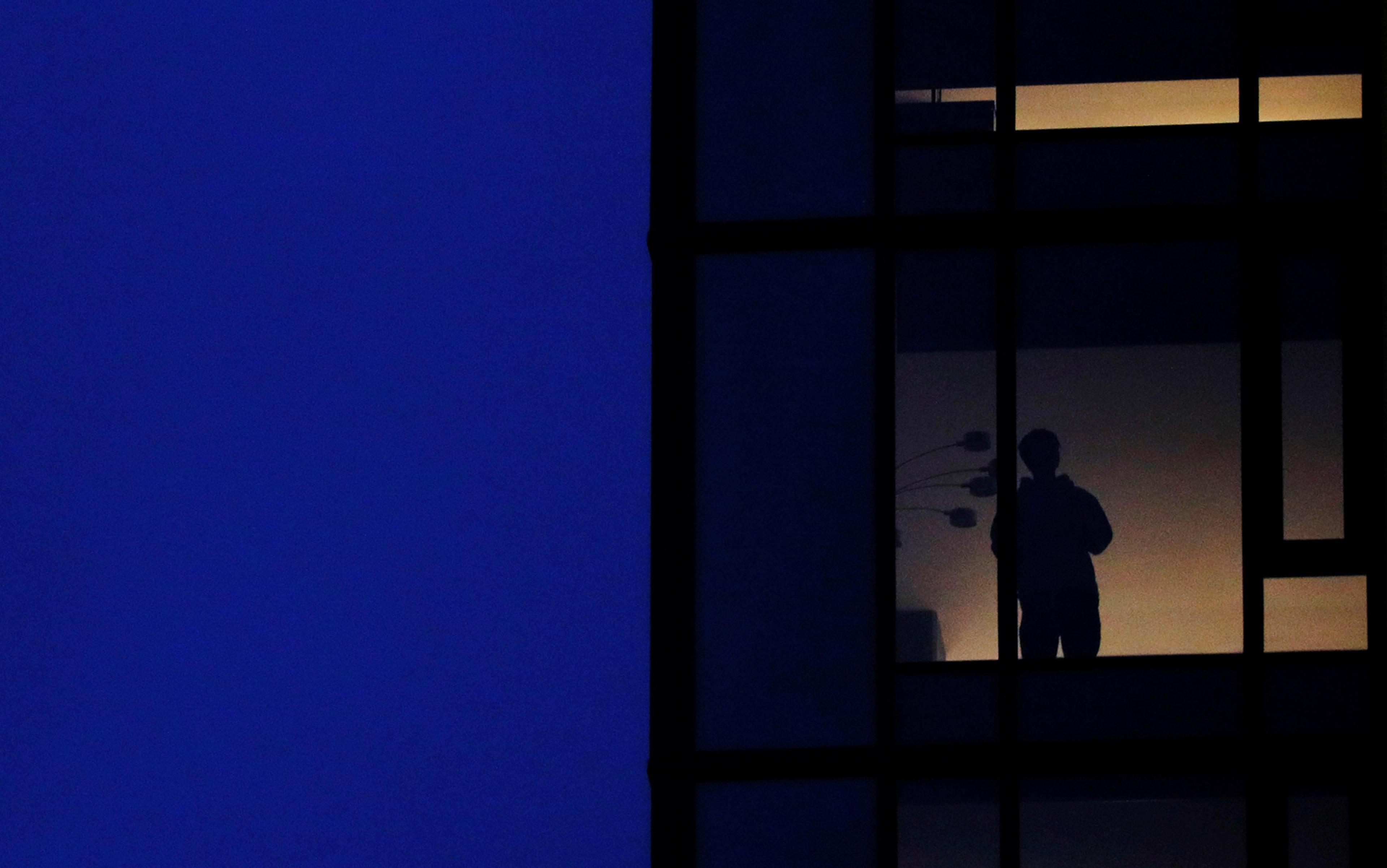

I find myself in the privileged position to be isolated with my family of four, with access to a garden. I imagine telling my younger son about how we spent the first few months of his life. The world that my children are set to inherit will have a very different social texture to the one that I grew up in, playing unsupervised in the cobbled alleys of Forlì. COVID-19 will become a hiatus in our lives, a time that will mark a ‘before’ and an ‘after’. Do you remember when we used to go to cafés and read the communal paper? we might say to one another. Oh yes, I do, before coronavirus. And after? It’s still too early for us to make any solid predictions. I only hope it’s not a society in which we’re all wearing masks, sipping our espressos at a polite distance, video-chatting with family members and friends far away.