On 22 July 2011, a 32-year-old man, disguised as a policeman, parks his van below the Regjeringskvartalet, a complex housing several offices of the Norwegian government, then walks off, abandoning Oslo city centre for his next – true – destination. Minutes later, a bomb detonates from within the vehicle. The explosion whips through the grounds, killing eight people and leaving many others critically wounded. But the man is already en route to the island of Utøya, a short boat ride away, where a children’s state-sponsored summer camp is underway. Here, over the next 90 minutes, his bullets mow down dozens of unsuspecting victims: 69 more people die, half of them minors.

Anders Breivik’s shooting spree was painstakingly planned and, in the manner of an old-style righteous revolutionary, extensively justified – in writing. In a manifesto running to 1,500-plus pages, Breivik couched his ethnocentrism within a re-tooled Nordic tradition and Aryan mythos that passed for ideology: at Utøya, his rifle and pistol bore inscriptions of the names of Thor’s hammer and Odin’s spear. Breivik’s makeshift philosophy may have been spun from ideological ponderings, pseudoscience and inflated statistics, but he aimed for an authoritative platform – a historic pairing of literature and action.

Action is central to the manifesto, but the notoriety that action receives is what makes or breaks its potential for impact. Where violent manifestors like the Unabomber Ted Kaczynski held the US media in his thrall, spurring a nationwide hunt and endless editorialising devoted to unravelling his psyche and writings, the manifesto by the shooter who killed 51 people across two mosques in Christchurch in 2019 is neither widely available nor deeply analysed. New Zealand’s then prime minister Jacinda Ardern urged against the use of his name, encouraging a media-wide ban, which denied the killer the oxygen that Kaczynski thrived on and the legacy he continues to enjoy (even in death).

The manifesto, then, is not a platform for creation, but for destruction; its author attains fame and influence on account of what they obliterate. If there’s nothing to show for their violence, they’ve been unsuccessful.

Breivik’s manifesto 2083: A European Declaration of Independence (2011) is a sprawling patchwork of disparate information, much of it plagiarised, that jumps from reactionary claim to dense theoretical history to practical guidelines for action. It is riddled with contradiction. Quotes from academics, such as the French political scientist Olivier Roy, bleed without distinction into Breivik’s own words; and he elides political Islam with Osama bin Laden’s brand of fundamentalist terrorism.

Breivik is chiefly concerned with the scorn in which social justice warriors hold fellow Europeans who suggest ‘that the traditional social roles of men and women reflect their different natures, or that homosexuality is morally wrong’. ‘What was their crime?’ he asks, and answers: ‘Contradicting the new EUSSR ideology of “Political Correctness”.’ Leaning on tried and tested ‘Red scare’ tactics, he writes: ‘Political Correctness is Marxism, with all that implies: loss of freedom of expression, thought control, inversion of the traditional social order, and, ultimately, a totalitarian state.’

Breivik intends his exhausting document to be a manual for actual violence

So far, Breivik’s rant is not much different from my uncle using Facebook to share pseudo-intellectual clickbait about the ‘woke agenda’. But his manifesto has a deceptive structure. Breivik’s way of forcing in ‘evidence’ – he claims that violent crime is disproportionately committed by Muslims; that AIDS is mostly acquired voluntarily – is a specific rhetorical move; what the scholar Jenny Rice calls ‘accumulation’, or simulating a sense of quality through sheer quantity. In Awful Archives (2020), she writes that the pile-up is there to ‘allow genocide to appear as bloodless bureaucracy … [to] give a shimmer of moral correctness to immoral acts.’

Still, roughly halfway through Breivik’s exhausting document, it is clear that he intends it to be a manual for actual violence. Everywhere his militant section-headers stress know-how: ‘Using terror as a method for waking up the masses’; ‘Avoiding suspicion from relatives, neighbours and friends’; or ‘Armour Phase – KT guide to ballistic armour’. He writes about how to acquire chemical weapons and how to bomb press conferences while evading capture. His manifesto is a sloppy mess of a document, thorough to a fault, misguided in its claims and irresponsible in its treatment of evidence. It would neither have been read nor commented on to any appreciable extent without the terrorist’s publicity stunt as its bat signal. Breivik’s rallying cry was a hail of bullets – and, whether literal or figurative, such bullets are the connecting thread between history’s most memorable manifestos.

Manifestos demand violence, whether sanctioning it, valorising it or gesturing towards it. In New York City, Valerie Solanas self-published the SCUM Manifesto (1967), her clarion call for brutal social change. ‘SCUM’ stands for Society for Cutting Up Men, and the manifesto calls for their extermination. Solanas’s manifesto can easily be read as a brilliant feminist satire, but then, in 1968, she walked into the artist Andy Warhol’s studio, shooting and almost killing both him and the art critic Mario Amaya. Suddenly, her manifesto, like Breivik’s the moment he parked that van beneath the parliament offices, became manifest. By ‘making good’ on her words, her words take on new meaning. Can we still read the SCUM Manifesto as satirical? Earnest? Or a manual for genocide? It’s quite possible that all these readings are now plausible, and Solanas’s influence has lingered on.

Even in its seminal literary and artistic forms, the manifesto has allowed political actors to spearhead revolutionary upheaval and radical action. In ‘Toward a Revolutionary Feminist Pedagogy’ (1965), bell hooks devised a teaching approach that, when used as a ‘tool’ by teachers, aimed to dismantle the hierarchies embedded in classroom dynamics. With The Communist Manifesto (1848), Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels provided a socioeconomic treatise that’s been foundational to countless activist initiatives and worker rebellions. Its closing passage declares that:

[The Communists’] ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions. Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communist revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains.

You might think the Surrealist manifestos – which tapped into childhood instincts, psychoanalysis and the symbology of dreams to kickstart an artistic revolution – were gentler creations. But their author André Breton claimed in 1930 that ‘the simplest Surrealist act consists of dashing down into the street, pistol in hand, and firing blindly, as fast as you can pull the trigger, into the crowd.’

The Dada Manifesto was performed as a provocation to reject all unoriginal ideas from previous centuries

The manifesto’s form seems to necessitate forceful upheaval. The manifestor wants to tear down an ‘old order’ and supplant it with something entirely new, always through extreme measures. For hooks, the old order is the barrier between professor and student; for Marx and Engels, the enemy is the upper class; for Breton, the constraints of reality. They all hate an existing thing, and use the manifesto to call for its demolition. The manifesto has always been a hate document. And where there is hate, there is violence.

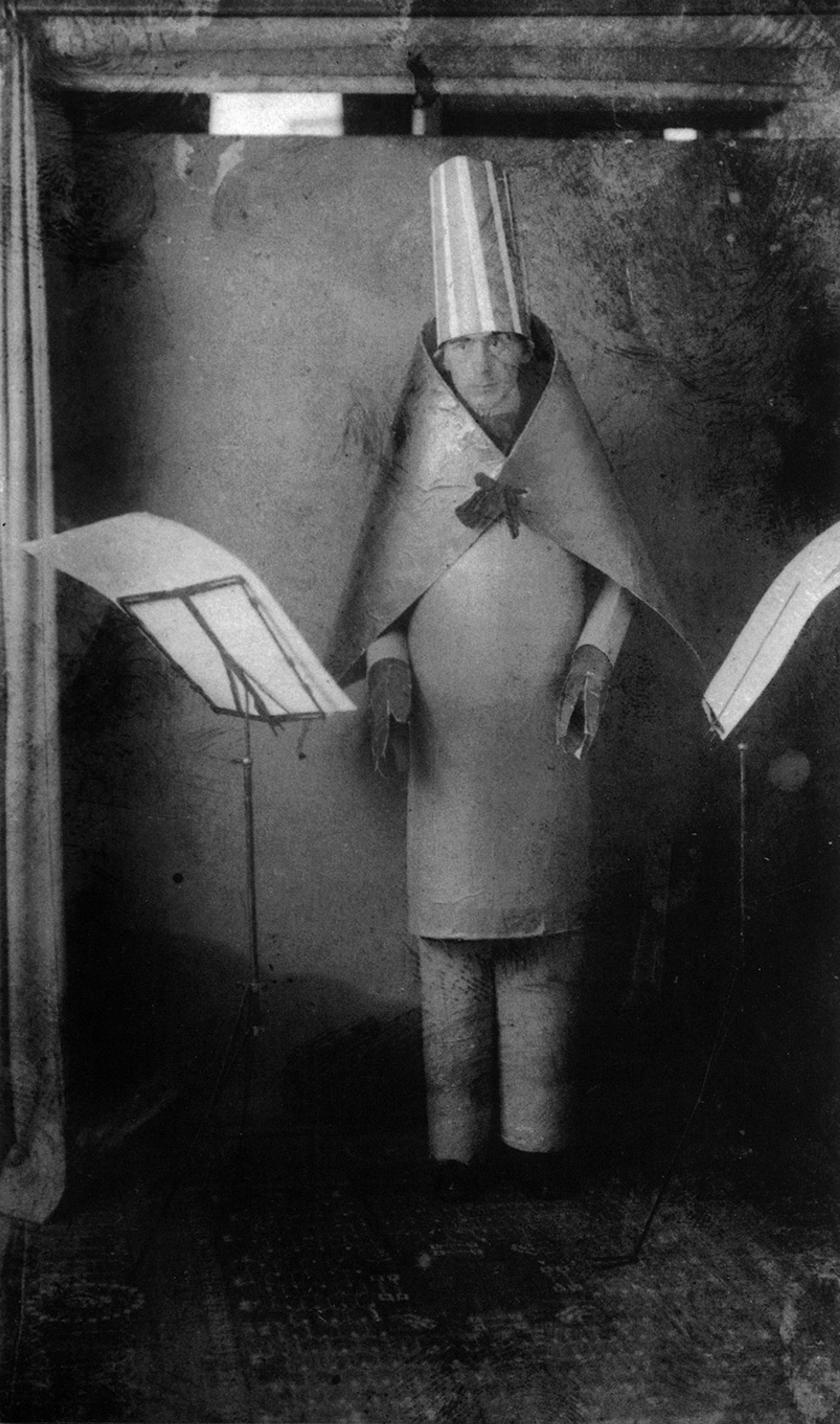

Hugo Ball (1886-1927), a Dadaist writer and poet, wearing a cubist suit made by himself and Marcel Janco for a recitation of his poems at Cabaret Voltaire, Zurich, Switzerland, 23 June 1916. Photo by Apex/Getty

Hugo Ball, author of the ‘Dada Manifesto’ (1916), called for nihilistic absurdity in the visual and material arts. His tumultuous performances of sound poetry and cabaret provocations unsettled critics and spectators alike. In one instance, he orchestrated a fake press release promising a showstopping duel between fellow Dadaists (and authors of other popular Dada manifestos) Tristan Tzara and Jean Arp. In another, Ball’s manifesto was performed to a Dadaist gathering as a provocation to reject all unoriginal ideas inherited from previous centuries. Marcel Duchamp would later put Ball’s principles to the test with his readymade piece ‘Fountain’ (1917) – a public urinal exhibited in an art gallery. Take that, art snobs!

The Futurist Manifesto (1909) by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti becomes progressively more exclamatory through its handful of pages, moving from itemised demands to multiple statements that end with exclamation marks and passionate cries for a new revolution in art. ‘We want to glorify war – the only cure for the world,’ says Marinetti, and: ‘We want to demolish museums and libraries, fight morality, feminism and all opportunist and utilitarian cowardice.’ Futurist hijinx included gluing spectators to seats, sprinkling dust in the theatre to cause sneezing, and selling multiple tickets for a single seat to generate fights. The Futurists are frequently criticised for revelling in the horrors of war; valorising guns, planes and steel, and the aerial technologies that made violence-at-a-distance possible; and for being precursors to later iterations of fascism and accelerationist ideas.

There is a tangible sense of blunt force – of bullets – to the manifesto. But if we examine it as a genre with clear, traceable patterns in rhetoric and composition, the manifesto may be seen as a device. Through the dynamic application of stylistic flourishes, the frantic pulling from different wells of information, and the continual experimentation with structure and genre, manifestors disperse their fiery claims across a hybrid document. The more they bombard our senses, the more open we become to their potentially bloody ultimatums. This is why Breivik always circles back to his hatred of political correctness, building to each condemnation using a barrage of stylistic tropes: long-winded stretches of history or theory; tedious lists of equipment procurements down to the precise measurement; biographical digressions on leaders in Marxist thought through the ages.

A tamer, but no less inventive example of rhetorical pile-up is found in the feminist punk movement Riot Grrrl’s guiding manifesto (1991), which makes use of ALL CAPS and ‘word collages’ in each of its declarative paragraphs:

BECAUSE we want and need to encourage and be encouraged in the face of all our own insecurities, in the face of beergutboyrock that tells us we can’t play our instruments, in the face of ‘authorities’ who say our bands/zines/etc are the worst in the US …

The Riot Grrrl community applied these ideas by shunning traditionally patriarchal recording and publishing outlets to focus on DIY zine-making and underground performance. Band members inscribed misogynistic language like ‘SLUT’ onto their bodies in protest at the music industry’s treatment of female artists. Their actions were as large and combative as their conjunctions and capitalised phrases on the page.

Be it up in flames or surgically removed, the manifesto’s target will have a fight on its hands

A manifestor’s engagement with violence, whether it’s aggressive language sharpied onto the body, or the gunning down of children, is a premeditated rhetorical act. It’s what makes the manifesto itself a performance as opposed to a static object: it possesses the power to communicate something of its own and stop an audience in its tracks. An act of violence amplifies the ethos of the writer and the legitimacy of their cause, adding flesh and bone (often literally) to mere words. Without the rhetorical effect of direct violence, the manifesto is just a literary rant.

Manifestos are not your usual five-paragraph essay, or editorial thinkpiece or essayistic article like the one I’m writing at the moment. They’re not even measured, posturing political speeches; as Breanne Fahs notes in ‘Writing with Blood’ (2019), manifestos are ‘wild-eyed calls to arms intended to provoke radical social change, often moving at breakneck speed and invoking the collective “we” as they envision a new world order.’ There is always a dimension of spleen and spite, an ‘us’ vs ‘them’, or ‘it’, or ‘everything’. And it all has to go. Be it up in flames or surgically removed, the manifesto’s target will have a fight on its hands.

Here is the explosive recipe we’re working with as we approach the manifesto’s present-day incarnation:

- Demonstrate a burning desire for change.

- Identify a clear target of blame.

- Remain committed to the intended goal, no matter how extreme the proposed solutions.

- Experiment with style and form for the sake of impactful rhetoric, expressivity and wresting attention from the reader.

- Promote ideas off the page through direct action.

A contemporary equivalent of the traditional manifesto doesn’t really exist. Did its recipe disappear? Has it been replaced by a new one? Not quite. It’s migrated online, reverted to the shadows, stretched like smooth taffy across the ether to grow less identifiable with each click. The modern manifesto is no longer a singular, blatant document touting a megaphone, but an underground extremist network fronted by professional interests.

Starting out in academia, figuring out my ‘niche’, I knew that there was this world of digital platforms and experimental ways through which to spread turmoil on the internet but, as a writing instructor, I was not yet fully exposed to it. I was setting up lesson plans on activist writing and hate writing, focusing on where to pinpoint logical fallacies, or discern argumentation that is productive, versus that which is destructive. I had been so entrenched in blatantly discriminatory content – media produced by televangelists such as Jim Bakker, literature like Thomas Dixon Jr’s novel The Clansman (1905) – that I almost missed the more expertly digitised hate content hiding in plain sight.

I’ll admit that researching manifestos is emotionally draining. The particularly noxious ones are so militant in their aims, so monastic in their commitment, that they double down on repetition, name-dropping and political rhetoric with a hammering intensity. Reading manifestos like these is like being programmed by a cult: there is no room for questioning. You either desensitise or break under pressure. A very likely reason as to why I didn’t catch the more subtle cases right away.

I stumbled upon a group called Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF), a purported ‘legal advocacy organisation’, when I was looking into activist content. Its website was reminiscent of an official US government webpage, with photography taken straight from a stock photo album, and hotlinks to its other pages on family growth and life events. It took a deeper dive to find that the ADF was borrowing list-format, reactionary rhetoric and fabricated data from the hate manifesto tradition. The organisation attempts to make a legal and biological case for why children raised by queer parents are doomed to mental illness or emotional immaturity. And it structures its FAQs to deter critics who might accuse them of ‘hate’.

The ADF’s website also has bulleted lists that pit the interests of the family against the individual’s. On the ‘Marriage’ side, they celebrate ‘A culture interested in strengthening the future with a commitment to others.’ Fantastic, that must be the side I should root for, since on the ‘Individual’ side they state that ‘individual desires trump what is best for society.’ Selfish! Further, on the ADF site, marriage means specifically a heterosexual relationship: anything outside that family type is relegated to the enemy side. In a slick embedded video, interviewees recount how growing up in a nontraditional family unit left them damaged. One man says that queer parenting is harmful to children, since he himself is bisexual and even he thinks his gay parents established an inhospitable environment in which to raise a child.

From within the funhouse mirror of these websites, the manifesto eludes accountability

The ADF doesn’t have to shoot people for publicity stunts as wild as the Futurists’ or the Dadaists’. It employs lawyers who bring legal action in the name of religious freedom. In the infamous case of Masterpiece Cakeshop in Colorado, the ADF successfully defended a bigoted cake artist who refused service to a gay couple. Hate had consequences.

What makes digital hate groups particularly insidious is that they contain recognisable manifestos – but dissolved in a soup. The tropes and structural checkpoints of the manifesto are all there but they’re collaged across webpages, massaged into embedded clips and soundbites, and rendered interactive through infographics. When a violent action occurs in the name of these digital manifestors, it’s not as easy to trace it back directly to one document as with Kaczynski (whose manifesto was published in full by The Washington Post in 1995) or Solanas (whose manifesto was out before the shooting). These groups are still radicals – let’s make that clear – but it’s no simple task to identify them as such when they’ve refracted themselves through the shiny enamel of digital tools and corporate marketing.

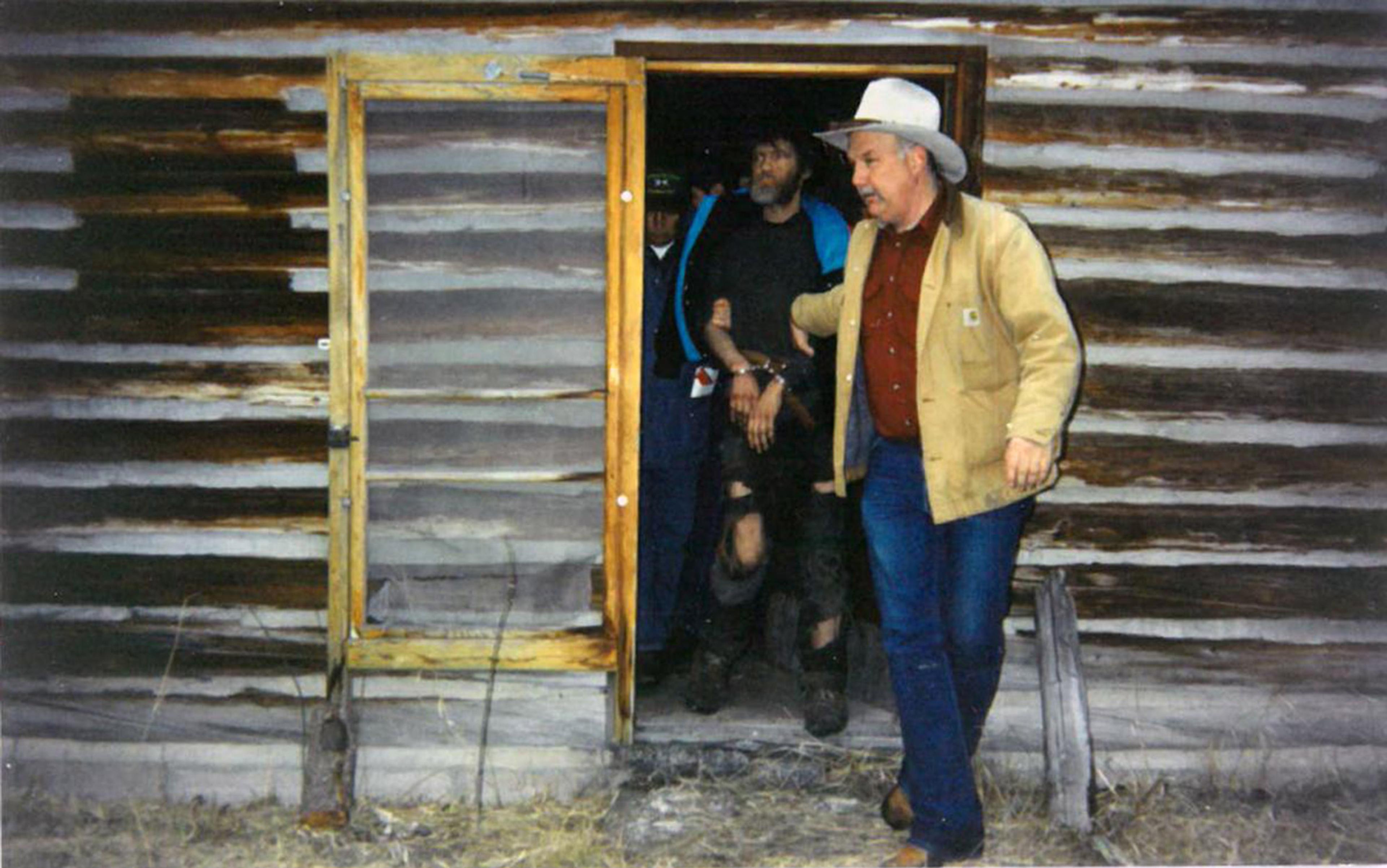

In a morbid sense, Breivik was the precursor to this. He is the ‘archetypal 21st-century terrorist’, as the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism called him – radicalised online, via the largely unregulated misogyny, racism and aggressive isolationism that characterises many chat forums and gaming communities. Breivik sprinkled his violent beliefs across an array of smart-sounding excerpts, buried his malice under piles of other people’s words, and signalled a new breed of radicals brought up on the internet’s dynamic frontier. Still, all he left was a single document. With ultra-contemporary agitators, it’s no longer ‘the Unabomber did this’ or ‘this small collective of artists started this’ – instead, we have organisations, partners, sponsors, affiliates, editorial staff, members and commenters, associated lawyers, and a rabbit hole of content to sift through. In the digital era, the manifesto remains as strong as ever, but it’s been sieved through a fine mesh. From within the funhouse mirror of these websites, it eludes accountability.

The New Black Panther Party’s website is challenging too, since it’s tied to ideas of Black liberation. Its textual content is reminiscent of a traditional manifesto (in the vein of the Riot Grrrl manifesto’s ALL CAPS words and run-on sentences creating greater emotional impact). It is also kinetic, in its big, bold font and its long, angry lists outlining the Party’s ‘revolutionary ideology’ and denouncing the age-old oppression of Black people. And yet, rhetorical oddities periodically pop up that cut right across the website’s antiracist declarations. Nestling within a critically insightful refusal for people of colour to participate in the military service of a country that is racist at its core, there is a condescending mention of the ‘Jews’ (in air quotes, just like that) having received their justice already, and several nods to antisemitic conspiracy theories linking Judaism to Freemasonry, the Illuminati, the Bolshevik Revolution, and basically world domination.

To get even more kaleidoscopic, Luxor Couture presents as a fashion boutique in Atlanta, run by women of African descent, until one realises that its website is a cover for a bookshop promoting conspiracy theories and antisemitic hate literature. They, too, draw influence from Breivik’s ‘accumulation’ methods: the more they stock their shelves with seemingly ‘antiracist’ and well-researched titles, the less it seems that they have anything hateful to say. Google the titles on offer, such as The Master’s Secrets: The Bloodlust and Religion by Malachi Z York, and you find that many of the books Luxor Couture sells contain Black liberation language that empowers people of colour at the cost of dehumanising others.

Luxor Couture also sells a title called The Fall of America (1973) by Elijah Muhammad, who led the Nation of Islam during 1934-75. The book contains long manifesto passages that sometimes call out the injustice of white America, and at other times employ misogynistic tropes:

The Black man should be sent to prison for being such a fool as to allow his wife and daughter to go out and show their nude selves to the public … Nudity originated from the white race. Now they want to say to the world that ‘I am the guide’.

As in Breivik’s manifesto, Muhammad’s perplexing statements burrow amid otherwise noble-sounding and well-intentioned passages of information. The new breed of manifestors have learnt well, using the digital space as a ‘Trojan horse’, rounded out with a smooth look and ‘progressive’ buzzwords, inside which they pack their hateful beliefs.

Luxor Couture is not just slyly dispersing its ideology through accumulation; it’s using an archive of for-purchase manifestos as a banner under which to carry forth, in digital form, its strategically hateful legacy. Marinetti offered a provocative idea about art’s complacency in the age of mass warfare, but he also endorsed mechanised destruction, duping people into confrontation with each other, and urging them to raze museums and set fire to libraries. Breivik presented history and theoretical discussion on Marxism, but he advocated for ethnic cleansing. Luxor Couture and the New Black Panther Party boast websites condemning the systemic oppression of Black people but they also believe in a global, insidious Jewish cabal.

The digital frontier leaves room for abundance – for an overload of tools, data and information that allows messages of hate and malicious publicity stunts to sprawl. To be scattered, repackaged and contorted across virtual spaces, as well as to hide beneath glossy and stylised facades. For instance, many anti-LGBTQ+ groups call for Drag Queen Story Hour to be removed from the schedules of local libraries, and have petitions to that effect on their sites. These petitions are not static. They can be shared and hyperlinked by other websites, by social media users and, ultimately, with enough backing, they can be used as leverage by attorneys who work for organisations like ADF. I’m intentionally keeping this vague so you don’t seek them out or consider signing.

Today’s digital agitators gain traction when masses of users latch on, sign and share those petitions, subscribe to channels, newsletters or listservs, and regularly follow a website’s content. And they gain traction when networks of like-minded people initiate legal action or campaigns in line with their hate agenda. When their ideas spread faster than wildfire, they don’t have to go out and acquire weapons, or open fire on a crowd, or send homemade bombs to their targets via snail mail. They don’t even have to lift a finger to type, because voice-to-text AI can do that for them.

These manifestos are so cold-blooded, they fit almost seamlessly within accepted corporate frameworks

Their interfaces resemble the bland institutional spaces of government websites and corporate landing pages; and the language they publish, at first, second, maybe even third glance, also resembles the rhetoric we would expect of trusted organisations. With web design tools at their disposal, they can intentionally misattribute a quote, or recontextualise an image, and those actions will be replicated tenfold, becoming further removed from the original context. With this breadth of opportunity, there is no limit to the hate speech that can be dressed up, diced into digestible pieces and institutionalised. Fake news framed as noble activism. In this world, the publicity stunt becomes community outreach, and the provocateur becomes the mobiliser.

We can see what digital hate looks like when it hasn’t carefully considered the effective tropes of the manifesto in its gameplan. In the case of Alex Jones’s Infowars, the website is pure sensationalism, with crude headlines such as ‘German Government Offers Kids Book Promoting Prostitution As Way To Make Money’ (2023) and overpriced, phoney products like DNA Force Plus, once touted as a cure for COVID-19. Infowars is the textbook definition of provocation, whereas organisations like the ADF legitimise their branding to a more sophisticated extent. Presumably they figured they’d be outed if they started ranting about chemicals in the water turning the frogs gay, as Jones once did.

Is the modern manifesto a digital document fuelled by hate? The answer, I’ve learned, is more complicated than a yes or a no. What signifies as a ‘document’ in the digital space – if that space even exists, divorced from all the other content surrounding it in an open tab or window? More often than not, digital manifestors distribute their theses, counterarguments and so-called evidence across an array of webpages, interactive resources and downloadable documents. The American College of Pediatricians claims to be a ‘national organization of pediatricians and other healthcare professionals dedicated to the health and well-being of children’. Meanwhile, under the cover of pushing scientific studies as its primary sources, it argues that the mother-father parental unit (sounds familiar!) is the only ethically sound structure in which to raise a child; that abortion is detrimental; that trans and queer identities should be discredited on scientific grounds; and that ‘sexual promiscuity’ is damaging US youth. The more rhetorically complex among hate manifestors use multimedia to establish an authoritative tone, expand their reach, and leverage their prejudice through legal avenues, professional advertising and ‘activist’ organising.

This new wave of manifestos is not what Fahs would call ‘hot-blooded and full of passion, unreasonable and “unprofessional” in tone, and revolutionary in intent’. Quite the opposite: they are so cold-blooded that they fit almost seamlessly within the accepted corporate frameworks of the online spaces we peruse with limited attention spans by the hour. They might be pulling from the manifesto playbook, but they’ve actually broken it into pieces and reassembled it into a whole new monster.