Who was Aaron Swartz? I never met him, though I’ve had dealings with friends of his over the years. The outline of his biography is a matter of public record: teenaged computer whizz gets rich, becomes a political activist and ends up in his 20s facing decades in jail for murky charges related to the misappropriation of academic journal articles. That much is on Wikipedia.

If that isn’t intimate enough, perhaps his character comes through in the tributes that poured onto the internet following Swartz’s suicide in 2013. The signature notes of tenderness, exasperation and awe, in reminiscences from Tim Berners-Lee, Lawrence Lessig, Cory Doctorow and many other notable mentors, certainly conjure a fleeting presence. Nevertheless, in the end, the person is irrecoverable, and those of us who weren’t lucky enough to know him never will.

‘What was Aaron Swartz?’, on the other hand, seems like both a tractable and a worthwhile question, not least because a decent answer ought to say something about where we are now. Swartz positioned himself at the exact spot where technology and politics press noses and glare at one another. It’s a Silicon Valley joke (or perhaps just a Silicon Valley joke) that every idiot with a dating app says he wants to change the world, but Swartz seems really to have meant it. He quit money the way PayPal’s co-founder Peter Thiel wants smart kids to quit college. He became a white-hat hacker among the levers of state power.

And things ended, not just badly, but dismally, in a sulphurous halfworld of G-men, prosecutorial intimidation and forced betrayals. It is, I suspect, impossible to learn anything about the young activist’s story without starting to see it as a symbol of something ominous in our present chunk of history. But what?

An all-round prodigy raised among computer enthusiasts, at the age of 13 Swartz created a website called ‘The Info Network’, an encyclopedia designed to be written and edited by its users. This was in 1999: two years before Wikipedia. The Info Network came to nothing, as did Swartz’s petition site, watchdog.net, a proto-version of change.org that he cooked up around the same time. But another project he co-authored did rather better: RSS became the standard format for online feeds (this website uses it and, if you have a site of your own, there is a good chance that yours does too). Then, in 10th grade, Swartz dropped out of high school.

While dabbling in a few different college courses around his family home in Chicago, he helped to decide the terms for Creative Commons content licences, the standard agreements under which creative works are shared on the internet. He did a stint at Paul Graham’s start-up incubator, Y Combinator, where he joined the team that founded Reddit, a commenting platform that came to be known as ‘the front page of the internet’. That site got bought out by the publisher Condé Nast, giving Swartz a sack of money and an unhappy few weeks drifting around the offices of Wired magazine. Any other young celebrity founder might have tried to repeat his entrepreneurial coup. By now, though, Swartz was interested in something bigger than mere success.

He helped to set up the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, a research organisation designed to steer US politics in a left-Democrat direction. Another group he co-founded in 2010, Demand Progress, became the centre of the campaign against the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA), a heavy‑handed attempt to prevent illegal file‑sharing by shutting down websites. Swartz was writing copiously on his Raw Thought blog: political screeds, tough-minded cultural commentary, reading lists, curious jokes. He also put his name to the ‘Guerilla Open Access Manifesto’, as pithy a statement as exists of his core political philosophy:

Information is power. But like all power, there are those who want to keep it for themselves. The world’s entire scientific and cultural heritage, published over centuries in books and journals, is increasingly being digitised and locked up by a handful of private corporations… We can fight back. Those with access to these resources – students, librarians, scientists – you have been given a privilege. You get to feed at this banquet of knowledge while the rest of the world is locked out. But you need not – indeed, morally, you cannot – keep this privilege for yourselves. You have a duty to share it with the world.

Perhaps it was in the service of this ideal that Swartz began a series of projects involving massive downloads of scholarly and legal archives. He created a script that worked through thousands of law review articles to determine whether corporate sponsorship exerted any influence on scholarly conclusions (guess). In 2008 he downloaded 2.7 million pages of federal court documents from the US Government’s PACER database and released them online. Why not? The documents were public domain anyway; the fact that the government billed you eight cents a page if you wanted to access them was rent-farming of the most obvious kind. The FBI investigated him for that, but no charges emerged. That round went to Swartz. But then there was JSTOR.

JSTOR (for Journal Storage) is an online repository of scholarly articles. It charges for access but – and this is the bit that sticks in the craw of open-information activists – contributes nothing to the content it hosts, which is the work of uncompensated academics. Nevertheless, the content is not public domain: copyright usually rests with the publishers.

he was smart: the kind of patient, brutally practical intelligence that actually accomplishes things

In the autumn of 2010, Swartz snuck into the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), a university of which he was not a member (presumably he would have had an easier time at Harvard, where he held a research fellowship), and set up a laptop to download as much of JSTOR as he could grab. Someone found the computer in a service closet and, oddly, set up a spycam to record its owner on his return. Swartz had to go back to switch a hard drive. And so he was caught on camera, and a little later, in the flesh.

It was never clear exactly what he intended to do with the documents he had obtained. On the face of it, his biggest crimes were trespassing and violation of MIT’s computer policy. Yet somewhere in the recesses of the law-enforcement apparatus, it appears Swartz’s card was marked. He learned that he faced charges of breaking and entering with intent to commit a felony; projected sentence: 35 years. MIT tried to wash its hands of the affair, but the prosecutor was implacable. The legal defence swallowed his Reddit money. Federal agents intimidated his loved ones.

Swartz had suffered from depression at intervals throughout his life. He seems, for example, to have considered suicide shortly after he left Wired, writing a story on his blog about a person called Aaron who kills himself after losing a job. The story is disconcerting, but Swartz freely admitted to an angsty streak in his creative writing, once referring derisively to his own ‘old tortured-psyche fiction pieces’. However, in 2013, at the age of 26, he actually went through with it. It was no longer possible to know Aaron Swartz.

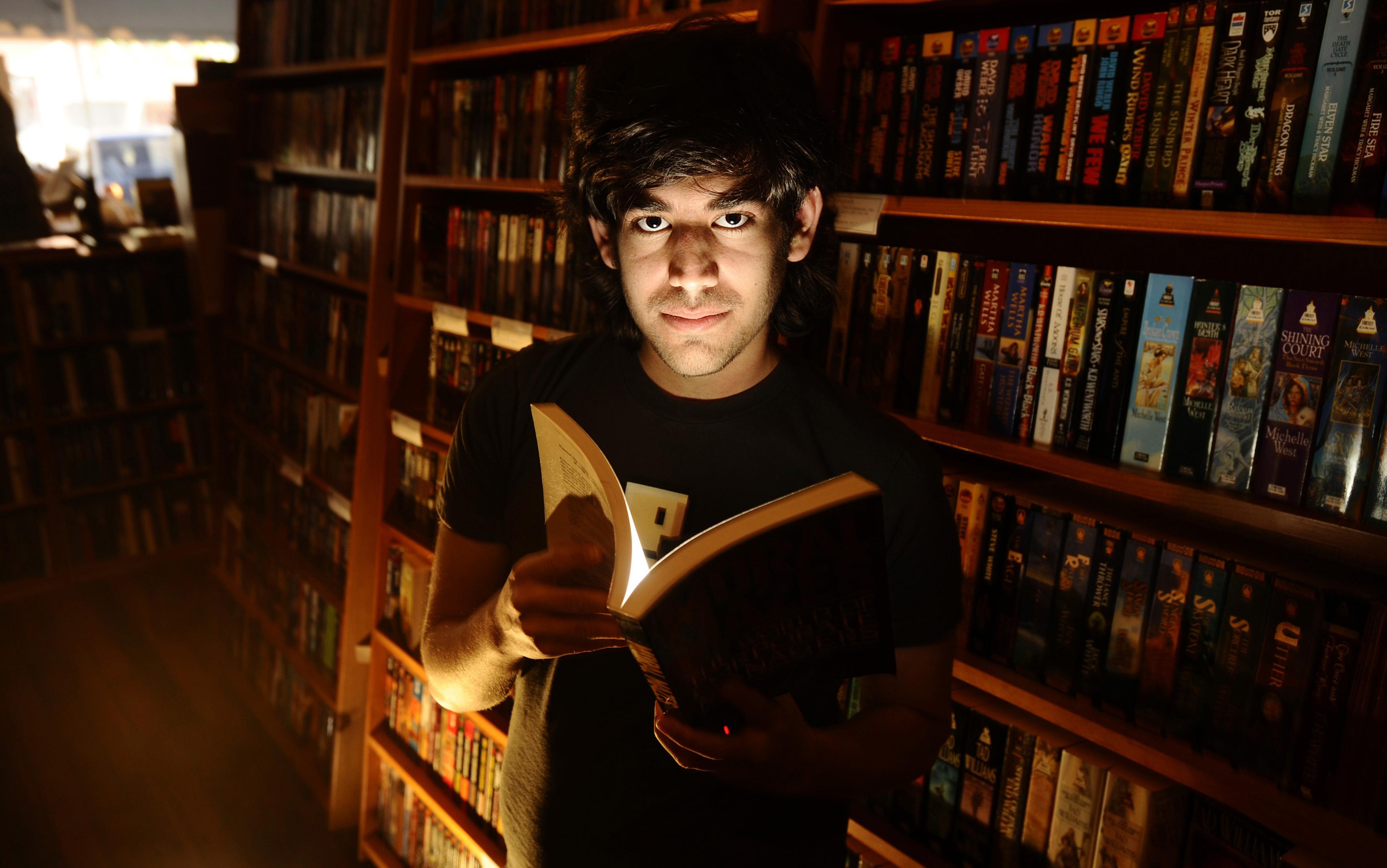

‘Growing up, I slowly had this process of realising,’ Swartz announces, gazing at the viewer with hypnotic self-assurance, ‘that all the things around me that people had told me were just the natural way things were… weren’t natural at all. They were things that could be changed. And they were things that, more importantly, were wrong and should change.’

This line, quoted close to the beginning of The Internet’s Own Boy (2014), Brian Knappenberger’s remarkable documentary about Swartz’s life, seems to contain our first key to the meaning of the whole. At first sight, it just sounds like ordinary youthful idealism. If we wanted to peg it on any specific political temperament, perhaps there’s an echo of old-style Fabianism – think George Bernard Shaw’s ‘When will we realise that the fact that we can become accustomed to anything… makes it necessary to examine carefully everything we have become accustomed to?’ And to a certain extent, the cap fits: Swartz surely does sit in that muscular reformist tradition.

But look at his autobiographical statement again. What is the implied sequence of discoveries? First, that things could be changed, and only then that they should be changed. Can precedes ought, not merely in the logical sense, but developmentally. I suspect that, for Swartz, this was really how it happened. He wasn’t, in the first instance, a dreamer who sought the tools he might need; he was a technologist who noticed some affordances and began to plot a course. He might have been naïve in various ways, but he wasn’t wishful.

‘The trick,’ he once wrote on the general theme of ambitious projects, ‘is to set yourself lots of small challenges along the way. If your start‑up is eventually going to make a million dollars, can it start by making 10? If your book is going to eventually persuade the world, can you start by persuading your friends? Instead of pushing all your tests for success way off to the indefinite future, see if you can pass a very small one right now.’ In short, I think Swartz is best understood as a very driven and ambitious sort of engineer.

Knappenberger’s film for the most part paints him as two rather different, and rather more familiar, sorts of protagonist. The first is the little guy, broken by an inhuman (or regrettably human) system. The second is the implacable revolutionary, boldly facing the future. Neither characterisation seems false, exactly, but they both miss the important thing.

Take the first. For the supposed crime of downloading academic papers without permission, Swartz really was facing 35 years in jail and $1 million in fines. He was an emotionally fragile 26-year-old with powerful enemies. The FBI was cruising around his neighbourhood, scaring him silly. The prosecutor wanted to make an example of him. Poor kid, right?

Well, yes. But at the same time, he was a good deal more powerful than that picture suggests. He had a comfortable cushion of money. His development work on RSS had given him enormous social capital among alpha nerds. Other influential friends opened doors for him in law, politics, the media. He was – you can see it in the extensive video interviews – intensely charismatic. And most enviably, he was smart: the kind of patient, brutally practical intelligence that actually accomplishes things (and this is to say nothing of his programming abilities). If it wasn’t for the precariousness of his mental state, it’s easy to imagine him beating the charges against him. Smaller Davids have beaten their Goliaths.

If not quite the little guy, then was he a revolutionary? He certainly looked like one, with his scrubby Che Guevara beard and plumes of hair. But if he was, it was of a very particular, rather technically minded sort – a far cry from the sacrificial lambs of the Arab Spring or Occupy. If he was dreaming of a better world, he was determined not to get carried away. (‘Can you start by persuading your friends?’) Swartz believed in crowds, but never leaderlessness. In fact he gave a good deal of thought to the dilemmas of command, examining, for example, the way in which companies, ‘even as they get big… betray facets of the founder’s personality’. ‘An organisation,’ he wrote in one of his final blog posts, ‘is not just a pile of people, it’s also a set of structures. It’s almost like a machine made of men and women.’ And those machines needed an intelligent engineer to make them work.

the world is changing anyway. Swartz was just one of the people who wanted to steer it

The political strategist Matt Stoller said that his friend Swartz approached politics just like he approached technology: ‘His method was as follows – (1) Learn (2) Try (3) Gab (4) Build.’ The pair hung around Congress, talking to lobbyists and policymakers. Swartz was learning the processes and the language, getting his head round the system. It was around this time that he started to talk (tongue not audibly in cheek) like the true heir to the spirit of the republic. Explaining to a TV reporter why he wanted to block legislation that would allow the government to shut down any website that hosted pirated content, he declared: ‘The principle is one that I think our founding fathers would have understood, if the internet had been around back then.’ Addressing a crowd on the same subject, he announces that SOPA would mean that ‘The freedoms guaranteed in our Constitution, the freedoms our country had been built on, would be suddenly deleted.’ Swartz was getting into character.

All the same, it’s strange to hear him presenting himself as a rediscoverer of old verities and an exposer of old lies. In reality, his domain was a sphere of near-total novelty. He was one of the people who found, or placed, a deep moral significance in the web. At stake in the battles over SOPA was ‘the right to connect’. Is there any such right? Since when? Listening to Swartz, you have the sense of a new moral order being conjured out of the confusion of the present. He was laying claims on the virgin territory of the internet, making space for concerns beyond the inevitable machinations of money and power. The naive activist wants to change the world. But that isn’t necessary: the world is changing anyway. Swartz was just one of the people who wanted to steer it.

In this, he seems much less like those sweet and hopeless Occupiers and more like one of the enigmatic, entrepreneurial operators who loom over our information politics. Edward Snowden is the obvious one; Julian Assange, too – men for whom ideology and opportunity seem inseparable. Add the (possibly pseudonymous) inventor of Bitcoin, Satoshi Nakamoto, to this list. Another who springs to mind is Mark Zuckerberg, whose claim that ‘Facebook… was built to accomplish a social mission – to make the world more open and connected’ reads as a kind of plasticky corporate take on the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto. In every case, the engineer has started to operate as a visionary improviser, seeing an adjacent world-state within the world system and instantly imbuing it with the radioactive glow of moral mission.

I admire them all, in different ways. Perhaps we need them. It can be difficult sometimes to see the internet as a collection of contingent ideas: it appears to unfold with a revolutionary logic of its own, so that the personalities of its vanguard party dissolve in the onrushing spirit of the age.

Perhaps, though, a version of what Swartz called Founder’s Syndrome applies, and the world we live in does after all ‘betray facets of the founder’s personality’, not only in the forms of our infrastructure but in the moral sense that we use to understand it all. In my list of great boy wonders, Swartz seems the most prepossessing of the lot, most animated by a consistent and recognisable politics. If nothing else, his moralising drew on a decent reading list. But as our lives are dominated ever more completely by complex computer systems, it is a little disquieting to realise that perhaps our heroes must be as alien and inscrutable as our problems.

Correction: the original version of this article stated that copyright in academic journal articles rested with authors.