I am not a gardener. A few square metres of paved back yard offered me little scope for horticulture as a London child. Faced with a larger square of neglected lawn that came with a later house, my parents were helpless and I absorbed their bafflement. Yet I am passionate about gardens. They promise escape and comfort, a place to read and heady pleasures for the senses. In however small a space gardens offer a connection to the larger natural world for which we hanker. As a non-gardener in a garden, you take your ease; but you also journey back to some more demanding, instinctive self who requires a glimpse of a lost paradise — ‘the flowery lap of some irriguous valley’ — as the poet John Milton had it, when Adam and Eve walked with God in the evening.

The British, of course, are mad for gardens — a hunger that is fed by countless gardening centres, gardening books, television programmes and newspaper columns, besides BBC Radio 4’s peerless Gardeners’ Question Time. So it is bewildering to note quite how disappointing many prize-winning gardens are. I’ve felt brutally let down by the annual Chelsea Flower Show in London, to which I’ve traipsed several times, only to find myself surrounded by bursting blooms, overcrowded and overripe, governed by a rebarbative design aesthetic. Once I stumbled upon Tom Stuart-Smith’s evocation of a hazel coppice in spring, a grove of flowering dogwoods with woodland plants beneath — phlox, tiarellas, pale-blue cranesbills and others I cannot name. But that was a daring exception to the dreary rule.

Chelsea’s show gardens appeal to the botanist and box-ticker, rather than to the lost souls of urban England

Chelsea is not an appropriate forum for the kind of planting and landscaping that you find at large country houses — like Rosemary Verey’s garden at Barnsley House in the Cotswolds, with its blend of formal lawns and ancient meadows; or Christopher Lloyd’s extended cottage garden, with its immense mixed borders and flowering meadows surrounding the manor at Great Dixter in East Sussex. But I’m puzzled that the poetry of gardening seems so elusive in formal contexts such as Chelsea. Gardening is an art, certainly, with rules and disciplines and many different tones, philosophies and styles. But there must be room for mystery, too, for what is artfully hidden as much as what is on display. It seems to me that the show gardens at Chelsea appeal to the botanist, the box-ticker, the admirer of individual species, rather than the lost souls of urban England looking for a solace provided by gardens that heal the rift between nature and man, or between the busy mind (eager to seize on geometries and concepts) and the dreaming subconscious.

So what is the hidden hunger that drives us all, not just the professional botanist, into the garden? What fantasies are we playing out in our various idealisations and realisations of gardens?

I‘ve been to gardens where my heart quickens and I recognise what I am looking for. A corner where old-fashioned rambling roses fly blowsily about a careful arch constructed from tangled sycamore, beech and ash; a meadow full of paint-bright wild flowers; a crooked line of worn stone steps fringed with ivy, running beside a silvery stream leading to a chilly pond with yellow flag irises and marsh marigolds; a colourful border with scented stocks and potentilla, delphiniums, peonies and cistus flaring for the day; parades of purple lavender blowing a French summer towards you.

There’s the majesty of a classical 18th-century garden such as Stourhead in the autumn, and the nostalgic floribundance of Sissinghurst, created in the 1930s by the writer Vita Sackville-West. There is a delight in a neat vegetable garden leading from cabbages to courgettes to the crossed bamboo canes training runner beans, and beyond, under nets, the raspberries. There is the beguiling allure of wayward profusions of nasturtiums spilling from a window box, or a sequence of square box hedges in the mist, the dew at their ankles hinting at the mysteries of all plant growth — from water and earth to these silent sentinels. Such gardens hint at stories, summon memories, suggest without hectoring; and in all of them the landscaping, the curves of shrubbery in a lawn, the terracing or layout of paths, the walls and gateways are as significant as the planting. These seem spaces entirely created to serve an inner hankering.

In his book Arcadia: England and the Dream of Perfection (2009), Adam Nicolson notes that this kind of gardening was born in Mesopotamia around 4000BC, alongside the earliest urban civilisations. Besides towns, temples and ziggurats, the ancient Sumerians built irrigation channels which brought water from lush marshy areas to the dry flatlands where cities grew. Succeeded by the Akkadian (c. 2380BC), Babylonian (c. 1900BC) and Assyrian (c. 1400BC) empires, the Sumerian vision was preserved in the evocations of gardens and groves found in the Akkadian Epic of Gilgamish. These enclosed outdoor spaces became images of watered perfection within the imperfect hubbub of the city. Indeed the Persian word for ‘an enclosure’, pairidaeza, is the source for our word ‘paradise’. We use gardens to cultivate food and medicine, and to extend interior design into the ‘outside room’, but for more than 2,000 years gardens have also allowed us to pursue a notion of abundance, ease and sensual beauty, where the cares of the world can be temporarily forgotten — even if the garden is as far removed from the realities of raw wilderness as from the human jungle of civic society.

Nicolson is a grandson of Sackville-West and the husband of the gardener Sarah Raven; together they live at Sissinghurst Castle. In his thoughtful book he explains how the idea of Arcadia fused a Greek vision of bucolic, pipe-playing innocence, with the evocation, by the Roman poet Virgil, of a beneficent, sensuous pastoral landscape, available to his leisured shepherds and shepherdesses as a setting for love and poetry. In England, the idea of Arcadia reached its ripest expression in the Renaissance. It is there in the poetry of Edmund Spenser and Sir Philip Sidney, whose prose work Arcadia (1580) was written for his sister, Mary Herbert, the Countess of Pembroke, while he was staying at her idyllic country estate, Wilton in Wiltshire. Here the idea of Arcadia was embodied as much in the landscape and gardens of the estate as in the conduct of life — the apparently timeless feudal relations between the lord of the manor and his tenants.

Peonies reach globed perfection just before they fall apart. As we lie in a flower-bordered dell, the midges come to bite

The idea persists in Shakespeare’s play As You Like It, as in the writings of Ben Jonson. And, at the tail end of its brilliant trajectory, Andrew Marvell writes in his poem ‘The Garden’ (c. 1650) how ‘the mind, from pleasures less,/Withdraws into its happiness … Annihilating all that’s made/To a green thought in a green shade.’ Marvell wrote the poem in the seclusion of his patron’s house at Nun Appleton, in Yorkshire — where the Commonwealth-supporting Lord General Fairfax had retired temporarily from the bitter political fray. Marvell’s garden is thus a place of refuge and healing from the psychological trauma of civil war. By the time Milton published Paradise Lost in 1667, our mortal link with this Arcadian vision had been broken. This ‘happy rural seat’ in Eden — where ‘Flowers worthy of Paradise, which not nice Art/In beds and curious knots, but Nature boon/Poured forth profuse on hill, and dale, and plain’ — was irrecoverable.

This highly wrought imaginative ideal was always fragile. And that, Nicolson notes, was part of its charm. The French Baroque painter Nicolas Poussin arranged his handsome shepherds in their golden landscape around a tomb with the enigmatic words inscribed, Et in Arcadia Ego, reminding us that even in Arcadia there is death.

Gardens are at their most delicious at sunset, just as the light turns fiery and fades. Peonies reach globed perfection just before they fall apart. As we lie in a flower-bordered dell, the midges come to bite. It is no wonder that it is so hard to find the garden that matches our imagination. As soon as you think you have it, reality — often dark, sometimes predatory — kicks in. In 1819, John Keats, sitting in a Hampstead garden, recorded that it was only while the nightingale sang that he could sustain the mental picture:

I cannot see what flowers are at my feet,

Nor what soft incense hangs upon the boughs,

But, in embalmed darkness, guess each sweet

Wherewith the seasonable month endows

The grass, the thicket, and the fruit-tree wild;

White hawthorn, and the pastoral eglantine;

Fast fading violets cover’d up in leaves;

And mid-May’s eldest child,

The coming musk-rose, full of dewy wine,

The murmurous haunt of flies on summer eves.

For gardeners wrestling with the brute circumstances of rough earth, weeds, insects, and weather, it is impossible to compete with the images conjured in poetry. Yet these images are largely responsible for shaping our hopes of what gardens might be. Even Keats, whose brother was dying, knew only too well that Arcadia is not possible on any patch of our Earth: gardening, like poetry, offers a brief respite from ‘the fever, and the fret’ but no permanent escape.

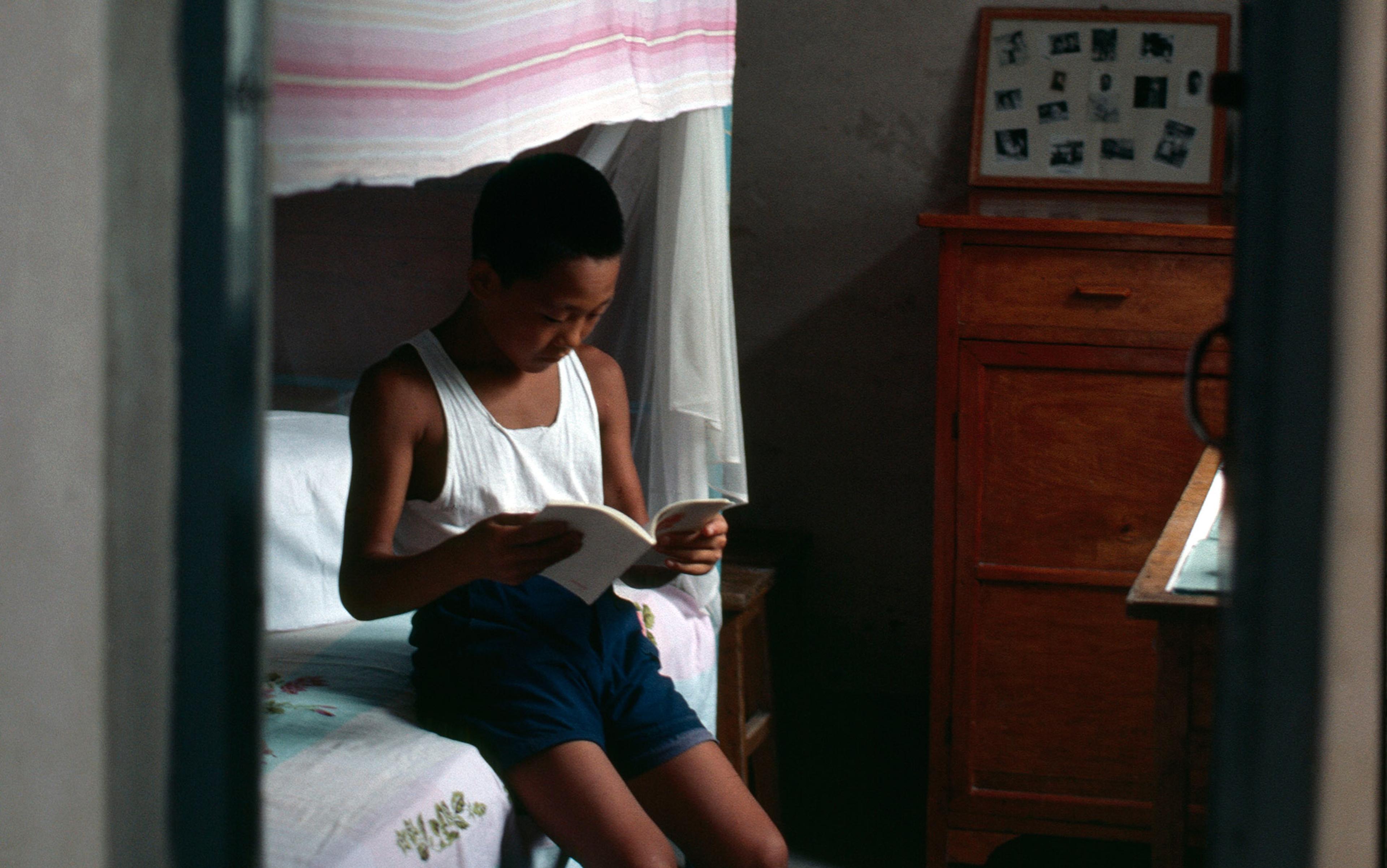

In the writings of the psychoanalyst Carl Jung, the Garden of Eden represents childhood — a period of life when nature and instinct give unstintingly. Gradually however, through childhood, adolescence and early adulthood, nature gives us over to consciousness and culture, effectively turning us out of the garden in a secular echo of the biblical fall. As Jung described the process in his 1930 essay ‘The Stages of Life’; ‘we are forced to resort to conscious decisions and solutions where formerly we trusted ourselves to natural happenings. Every problem, therefore, brings the possibility of a widening of consciousness, but also the necessity of saying goodbye to childlike unconsciousness and trust in nature.’

Jung believed that we are culturally haunted by this loss: ‘The biblical fall of man presents the dawn of consciousness as a curse.’ And so we long to return to the garden: ‘Something in us wishes to remain a child, to be unconscious or, at most, conscious only of the ego; to reject everything strange, or else subject it to our will; to do nothing, or else indulge our own craving for pleasure or power.’

Undoubtedly, gardens offer just such an opportunity for some people, where gardening is a kind of play — a chance to fashion an entire kingdom to suit your own unfettered fancy. For others, it is about a darker kind of subjugation. For the Victorian critic John Ruskin, gardening was certainly about the desire to return to his childhood and recreate the experience of Edenic bliss. In Modern Painters, Volume III (1860), Ruskin wrote: ‘The first thing which I remember as an event in my life was being taken by my nurse to the brow of Friar’s Crag on Derwentwater.’ This was the childhood memory to which he clung when, in 1871, he bought the paradisiacal, but dilapidated, Brantwood estate on Coniston Water in the Lake District — ‘near the lake-beach on which I used to play when I was seven years old’.

Ruskin set about restoring the house and gardens. There had been formative visits to the Lake District with his parents when very young, which burned that landscape on his imagination, but otherwise he had grown up in south London, at Herne Hill and Denmark Hill, in houses with substantial gardens that he and his mother tended. Years later, he reported that, aged four, this ‘little domain answered every purpose of Paradise to me’.

At Brantwood, Ruskin set about the combined strategy of creating a wild flower and rock garden (William Robinson had just published his hugely influential book, The Wild Garden, in 1870) and importing the apple trees and cherry trees that he had loved in Herne Hill. As he succumbed increasingly to mental breakdown, Brantwood became his sanctuary.

But gardens can also be a place for discovering the dark and the strange, the ‘not-I’ that must become the ‘also-I’. Think of such classic novels for children as The Secret Garden (1911) by Frances Hodgson Burnett, or Tom’s Midnight Garden (1958) by Philippa Pearce, where gardens are places for cultivating adult resourcefulness as well as roses, and confronting demons as much as those dreaded weeds. As Andrew Marvell noted, the garden is like Eden because it also contains the serpent.

Now I live surrounded by the garden my husband grew up in: without a car or much alternative entertainment, this garden was his world. As he works now on the paths and hedges, on reinstating beds and lines of view, he knows that he is digging down into those memories. He laughs that he spent his childhood being nagged by his mother to help her; yet now that he is free to make the garden entirely to his own pleasing, he has unconsciously set about recreating a more pristine version of hers. This is very far from the square of paving I grew up with, but my response to it is governed by the yearnings first kindled back then. If not quite Arcadia, it has in muddy patches hints of bliss that go far beyond the sterile perfectionism of the show garden.