Saul Villeda, who leads a stem-cell research lab at the University of California, San Francisco, is not concerned about a black market for baby blood. ‘You sound like my mother,’ he told an anxious reporter for the New York public radio station WNYC’s science programme Radiolab in an interview last year. ‘She’s worried that all of a sudden 16-year-olds are going to go missing.’

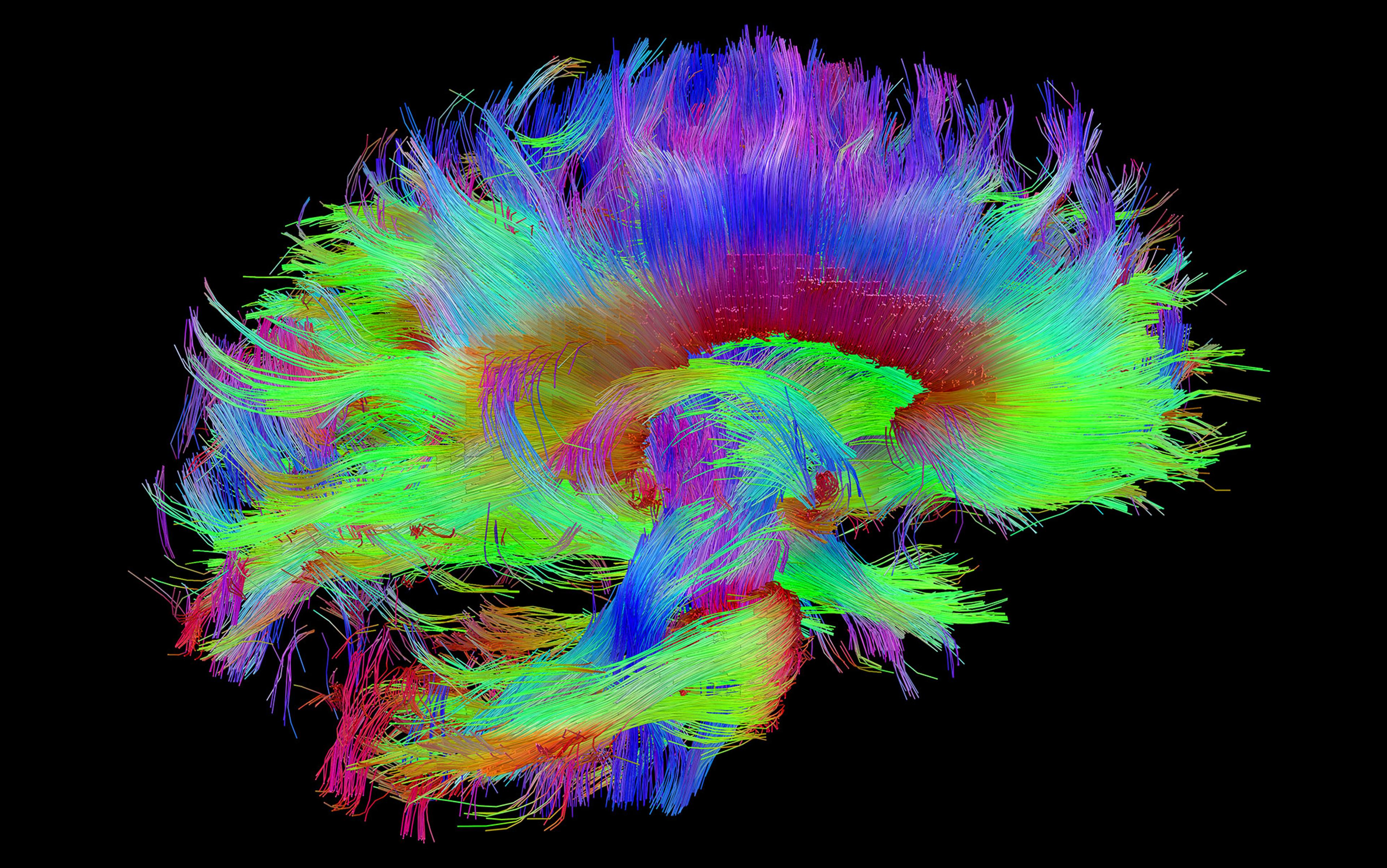

Villeda’s mother has reason to worry, sort of. Her son’s research has found that blood from young mice can improve the learning and memory of old ones, and she’s certainly not the only one to wonder what this could mean for humans. In his lab at UCSF and his postdoc lab at Stanford, Villeda and colleagues injected old mice with blood plasma from young mice, and vice versa. They found that the senescent rodents learned quicker and grew more neurons after infusions from young blood, while the juvenile mice got correspondingly worse at learning new tricks. On Radiolab, after the reporter Lynn Levy explained just how much the young blood revitalised rodent brains, you could just picture the host Robert Krulwich, who is in his 60s, swivel his head menacingly towards his younger co-host Jad Abumrad. ‘Jad?’ he purred. ‘Come a little closer.’ Abumrad, laughing hysterically, yelped: ‘Stay away from me!’

‘It freaks me out a little bit,’ says Levy. ‘I feel like old women will be buying vials of baby blood.’ She’s not alone. Commenters on CNN’s online coverage of the research sounded just like Villeda’s mother. ‘There’s gonna be a rash of old people kidnapping young people and harvesting their blood,’ one wrote. Another asked: ‘I wonder how long it will be before poor teenagers are disappearing.’ One budding entrepreneur offered: ‘As a young person I will sell blood to the highest bidder.’

Krulwich is probably not going to actually drink Abumrad’s blood, but that’s the first place his mind went, along with the minds of Levy and Villeda’s mom and the commenters on CNN.com. Faced with the knowledge that the bloom of youth is transmissible, they all thought: ‘But what’s to stop old people stealing it from the young?’

This lust for youth has been around for a very long time in human culture. We don’t always try to steal youth outright, of course. There are also creams, potions, diets, regimens and incantations, dating at least back to the oldest surgical treatise, a 1600 BCE document known as the Edwin Smith papyrus, but likely reaching back before written language. But there is also a long history of renewed vitality coming at the expense of the young. Pope Innocent VIII, who died in 1492, might have been the first to imbibe the blood of young boys in an attempt to stave off the inevitable. (It didn’t work – the boys died and so did the Pope – though it’s also possible the whole thing is a scurrilous rumour.) A 16th-century Italian alchemist recommended shutting children under the age of 13 in a well-enclosed room, then siphoning out the air, which would be ‘filled with the breath and expired substance of these five young virgins’ and therefore have curative powers.

Like many of our most puzzling and fundamental errors, this one is the result of cognitive bias. No matter how much a culture congratulates itself on being science-minded, we wrestle with a deep-seated tendency towards magical thinking – in this case, sympathetic magic, the idea that one can exert magical influence through contact or kinship. As described by James Frazer in The Golden Bough (1890), sympathetic magic has two forms: ‘first, that like produces like, or that an effect resembles its cause; and, second, that things which have once been in contact with each other continue to act on each other at a distance after the physical contact has been severed.’ Taking pills of powdered animal penis to cure impotence would be magic of the first type; magic of the second type might include a voodoo doll seeded with fingernail clippings from the victim.

The first type of sympathetic magic, which Frazer also calls homeopathic magic, is deeply ingrained in the history of medicine. Frazer describes sympathetic magical cures for infertility, tumours, difficult childbirth, and other medical complaints. For instance, he reports that ‘the ancient Hindoos’ wrapped jaundice sufferers in the skin of a red bull, in the hopes that they will take on its ruddy colour. Folk medicine often posits that plants and herbs treat the organs they resemble; the pendulous tubers of orchid root, for instance, were supposed to be good for testicle health. The Renaissance physician Paracelsus believed that the body was a microcosmic version of the universe, with direct analogues for each organ in the planets. In 1796, the German doctor Samuel Hahnemann invented homeopathic medicine on the principle that ‘like cures like’.

It’s only in recent centuries, as old age has become more commonplace, that we have started to venerate youth

As the Missouri State University psychologist Carol Gosselink has pointed out, this species of magical thinking also extends to the way people think about old age. ‘The largest numbers of magical thinkers about ageing,’ she writes, ‘are the countless midlife and older people who squander incalculable money, time, and energy on products and services promising that the disease of ageing can be slowed, stopped, or reversed by anti-ageing products and services.’ It’s no surprise that these new magic users are swayed by a medical finding that suggests like may truly cure like.

Most of the cultures Frazer documented in 1890 do not, at least in his description, have potions or incantations for achieving youth via sympathetic magic. As Gosselink points out, old age was so rare in less-developed societies that people who achieved it were granted a certain amount of status and even a mystical cachet. Later, the elderly might have been mocked or isolated, but age was still not seen as an illness. It’s only in recent centuries, as old age has become more and more commonplace, that we have started to venerate youth; ageing is now associated not with fortunate longevity but with decrepitude and disease. And accordingly, our magical thinking has expanded to find mystical cures for loss of vitality. That’s why a strange light appears in people’s eyes when they hear about the mouse blood experiment. We are culturally primed to look to sympathetic magic as a means for curing what ails us, and old age is now regarded as a disease to be fought.

One day in the early 17th century, the recently widowed Hungarian countess Elizabeth Báthory went for a ride with a suitor and spotted a withered old woman. Báthory playfully asked her admirer: ‘What would you do if you had to kiss that old hag?’ ‘God save me from such a hideous fate,’ he said. This pleased Elizabeth, until the old woman looked her way and warned: ‘Take care, O vain one, soon you will look as I do.’

The countess was in her 40s at the time, and she began to fret obsessively about encroaching old age. When, sometime later, she struck a servant, the girl bled, and Báthory noticed that her own hands became smoother and younger where the blood touched them. This gave Báthory, who was a particularly vicious master and whose servants were only peasants, an awful idea. She would kill her servants and take daily baths in their blood to keep herself young.

This is a total myth, of course. Elizabeth Báthory did murder girls – between 40 and 650 of them, depending on which account you trust – but there’s no evidence that she was turning them into wrinkle cream. While the accomplices and witnesses examined at Báthory’s trial did not stint at giving gruesome testimony about her crimes, not one of them mentioned the famous baths of blood.

A person who kills in order to steal her victims’ youth is, to some shameful corner of the brain, understandable

Nevertheless, the legend of Báthory’s ghastly toilette was stated authoritatively by the scholar László Turóczi in 1729, repeated as fact by historians in the 18th and 19th centuries, and still persists today, even after the witness accounts were made public. The introduction of Valentine Penrose’s book The Bloody Countess (1962), one of the first works to focus on Báthory, begins: ‘This is the story of the countess who bathed in the blood of girls’ – even though the book excerpts some of the very testimony that proves she likely did not. Gore-soaked Báthory avatars have appeared in fiction and film, including Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), which was probably inspired in part by the countess. Why is this image so indelible? Though Báthory’s murders were sensational, she has more hold on us as a proto-vampire than as a mere serial killer. The notion of stealing youth is so magnetic that it transcends fact.

The idea of the countess lounging in a bath of blood is no more dramatic than any of the true details of her crimes, which include a suspended cage full of knives, and an iron maiden decorated with real pubic hair. It persists not because it’s unusually lurid, but because it’s unusually plausible. A person who kills out of pure cruelty is a terrifying psychopath. But a person who kills in order to steal her victims’ youth is, to some shameful corner of the brain, understandable – which is, in many ways, more terrifying still.

If Báthory had been said to bathe in the blood of lambs instead of girls, would she be considered a monster? In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, she might have been lauded as a genius. In 1890s Paris, Charles Édouard Brown-Séquard promised rejuvenation – not to mention the reversal of many diseases – thanks to injections of ‘testis extract’. The testicles were thought to secrete a hormone that promoted youth, health and vigour. Some fashionable surgeons – notably Eugen Steinach, whose patients included the poet W B Yeats – advocated cutting the vas deferens to maintain these secretions in the body, but others, such as the surgeon Serge Voronoff, would physically remove healthy testicles from young animals, or even humans, and implant the glands into their patients. The vitality provided to a goat or monkey by his testicular secretions could supposedly be rerouted into the body of a human, with near-miraculous revivifying effects.

The idea of stealing youth, irresistible since before Báthory’s time, had no less appeal when the donor was an animal. (Though they weren’t always – in early experimental gland grafts at San Quentin prison in California, testicles from executed prisoners were implanted into living ones.) The medical profession might have been cautious (whether the donors were goats or convicts), but the public was convinced. People were so persuaded of grafting’s efficacy that the ethical discussion about the San Quentin experiments centred not on whether the procedure would work – of course it would work! – but on whether it was acceptable to extend a prisoner’s life. Meanwhile, in 1927, a Hungarian insurance company refused to pay an old-age annuity to a graft recipient, claiming that the operation had made him effectively younger than his physical age. One patient, Arthur Evelyn Liardet, intimated to The New York Times that, with the help of a few more monkeys, he might live to 150.

You can pick up skin cream made with sheep placenta or stem cells right here in the US

Gland-grafting fell out of favour by the 1930s, but it was replaced with cell therapy, which involved chopping up the organs of foetal animals and injecting them into the patient. Here, there were two kinds of sympathetic magic at work: the belief that healthy young animals could be sacrificed to rejuvenate humans, and that organ functioning could be boosted by injections of the same organ’s cells (a sheep’s liver shot would revivify an ailing human liver, for example). In 1953, more than 450 years after Pope Innocent VIII tried to cheat death with the blood of young boys, Pope Pius XII called on the cell therapy giant Paul Niehans to treat his fatigue and gastritis with injections made from embryonic sheep. The Pope recovered, though he later called on Niehans again to cure a crushing chest pain incurred after he tried to lift a heavy safe; Niehans diagnosed a diaphragmatic hernia, which he cured by oral infusions of specially prepared cells from full-grown Solanum tuberosum. In other words, he made the Pope eat a lot of mashed potatoes.

Niehans’s cell therapy clinic is still operating in Switzerland. For an undisclosed price, plus the cost of a hotel room, you can receive a course of revivifying injections of embryonic cells, plus ‘skin extract’ to rejuvenate your face – and for an extra fee they’ll throw in a pedicure. If you don’t want to go all the way to Lake Geneva, you can pick up skin cream made with sheep placenta or stem cells right here in the US. (‘Are these medical-miracle cells the secret to tricking ageing skin into acting young again?’ asked Elle of the stem-cell creams in February 2013. Miracle indeed.) Like Frazer’s research subjects hoping that the rosiness of bull hide would transfer to the jaundiced patient, we believe that, if we’re near youth, if we can ingest it or inject it or rub it on our skins, we’ll be able to harvest some of its power.

We might think ourselves superior to the inventors of the Báthory myth, but the idea of stealing youth still permeates popular culture today. In an episode of the US TV series The Simpsons called Blood Feud, for instance, the ancient Mr Burns is revitalised by a transfusion from 10-year-old Bart, who shares his rare blood type. After the procedure, the usually decrepit Burns glad-hands his way around the nuclear plant he owns, trilling cheerfully: ‘Hey there, Mr Brown-Shoes! How about that local sports team?’ ‘It’s funny, Smithers,’ he muses to his obsequious right-hand man. ‘I’ve tried every tincture and poultice and tonic and patent medicine there is, and all I really needed was the blood of a young boy.’

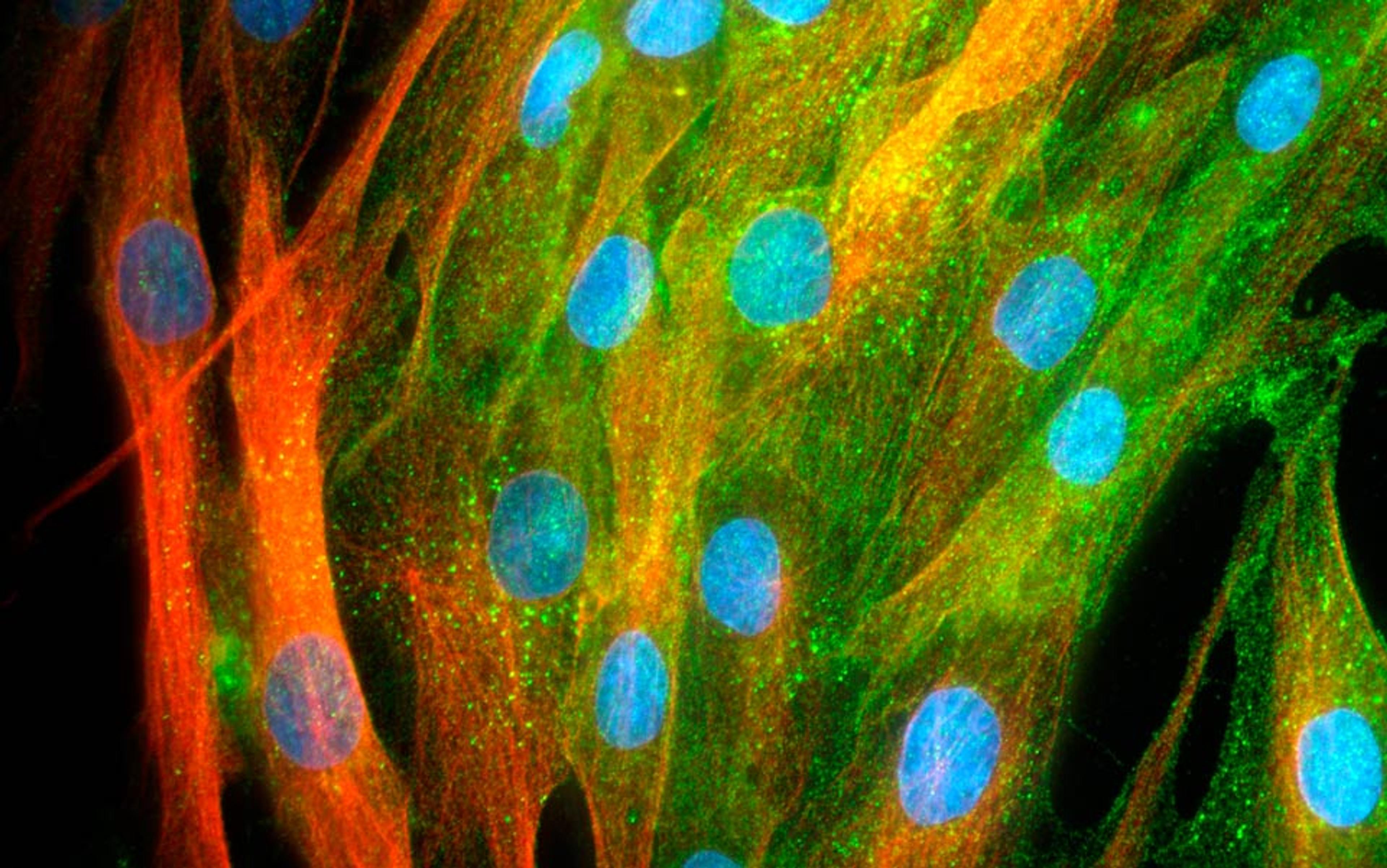

But now, there is scientific evidence that Mr Burns was right. The mouse blood studies out of Stanford and Harvard aren’t fiction, like the Báthory legend, or pseudoscience like Voronoff’s transplanted glands. They are rigorous investigations. And they suggest that something in the blood – possibly the protein GDF11, the subject of two recent Harvard studies, which is also present in humans – has the capability to reverse many of the effects of ageing. Amy Wagers, the lead author of one of the Harvard studies, discovered more than a decade ago that when old and young mice were joined via parabiosis – a procedure where the two animals are surgically attached so that they share a circulatory system – the old mice benefited while the young mice suffered. The recent studies zero in on the cause, showing that injections of GDF11 proteins can work almost as well as parabiosis, and they also expand our knowledge of which old-age ailments young blood can cure. We now have solid reason to believe that the old can become young again, at least in terms of memory, muscle strength and blood flow – but only at the expense of the young.

‘It’s better to have a good ageing rather than to become young again’

In the wake of these studies, it’s easy to imagine apocalyptic young-adult novels featuring blood farms where youth are drained on a regular schedule, or horror stories where teens are forced to literally sew themselves to the elderly. But Lida Katsimpardi, the lead author on the other Harvard paper, hastened to assure me that any medication developed from the mouse blood studies would involve synthetic proteins: ‘We don’t need actual blood.’ There will be no harvesting, voluntary or otherwise. Of course there won’t. When people are diabetic, they use synthetic insulin, not secretions ripped from the pancreas of a cow (or a person). Even therapeutic human growth hormone, explicitly marketed as ‘human’, is made in the lab through a recombinant DNA process. When we find that someone needs testosterone supplementation, we don’t force him or her to get monkey testicles implanted – at least, not anymore. The threat to the bloodstreams of tomorrow’s youth is all in our heads.

Katsimpardi has lofty ideals; when we spoke, she seemed indulgent but mildly weary of the fixation on using the research to make people younger. ‘It’s not really about rejuvenating everyone,’ she said. ‘It’s about finding factors to help with neurodegenerative diseases.’ Her grandmother died of Alzheimer’s, she told me, and while she had never seriously thought that she could discover a treatment that would prevent her from suffering the same fate, she’s long been fascinated with ageing – not how to prevent it, but how to make it happen in a healthier way. ‘It’s better to have a good ageing rather than to become young again,’ she said.

But if the new mouse research is going to help us age better, it will have to confront centuries of magic-fuelled medicine, and a folkloric and pseudoscientific literature replete with youth-stealing rites. The thought of this kind of vampirism – at once attractive and repulsive, horrifying and irresistible – is as ingrained in our psyche as any other superstition, and all the harder to banish because our fear of death and disease is so strong. That’s the challenge for anyone who eventually wants to adapt this research into something therapeutic: the ghost of Báthory on all our shoulders, whispering: ‘Youth is wasted on the young.’