In 1969, when the design guru, futurist and consummate bullshit artist Buckminster Fuller’s new book about the future prospects for humanity came out, he’d called it Utopia or Oblivion. It appeared on bookshelves and in college students’ backpacks just as three decades of unparalleled growth, prosperity and modernisation in the United States came to a grinding, confidence-eroding halt. Jump ahead just a few years, and it seemed pretty clear to most people which path society had placed itself on. Despite today’s sheen of Day-Glo nostalgia, the 1970s were saturated with dark, doomy and unsettling currents. Survival supplanted revolution as the new decade’s vital watchword.

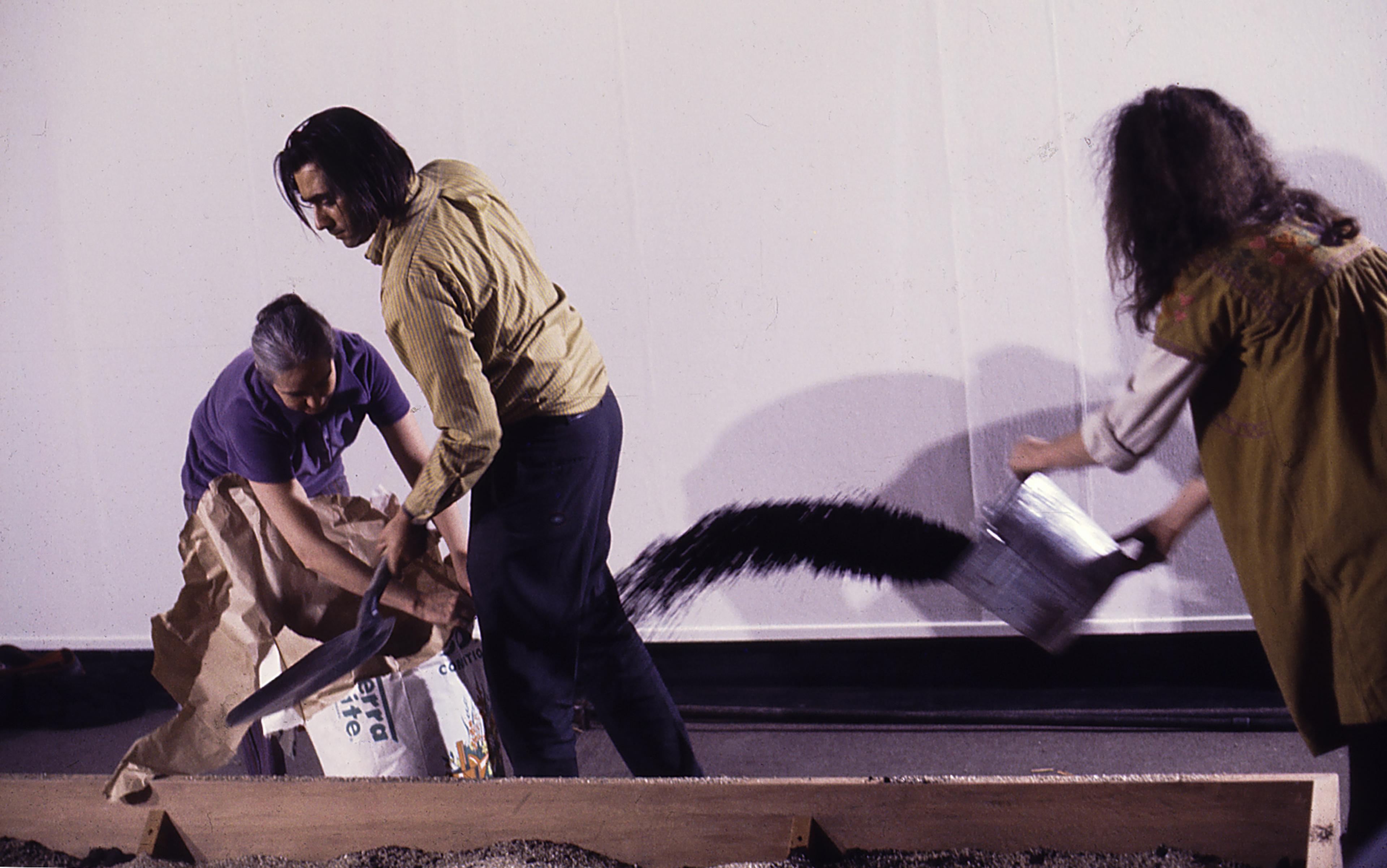

Survival Piece VI: Portable Farm (1972), at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, Texas. Photo by Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison

Americans found themselves grappling with existential threats on two fronts. The first was economic. Starting in the summer of 1971, the Richard Nixon administration enacted a series of economic reforms designed to stabilise the dollar. At that time, inflation and unemployment rose to about 6 per cent. The subsequent ‘stagflation’ that resulted was fuelled further by the 1973 oil crisis. When Gerald Ford replaced Nixon as US president in 1974, inflation had risen to around 10 per cent, unemployment to around 5.6 per cent, and a powerful recessionary wave hit the US and rippled outward through other countries’ economies. Not captured in bloodless statistics, however, is the surge in divorce rates, mortgage foreclosures, repossessed cars and other personal hardships and humiliations. I grew up outside of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and have distinct memories of food banks, shuttered mills and handouts of ‘government cheese’ that began during the Jimmy Carter years and continued into the 1980s.

The second push toward pessimism flowed from Americans’ anxiety about the deteriorating quality of the environment in the US and throughout the world. Throughout the 1960s, politicians, scientists and activists saw the planet as analogous to a spacecraft, a fitting comparison during the Apollo era. The idea that the Earth was, as the poet Archibald MacLeish wrote in 1968, a ‘tiny raft in the enormous empty night’ contributed directly to a profound sense of the planet’s fragility, which had taken hold by the early 1970s. While photos of the Earth from space showed a small blue marble floating in the inky blackness of space, environmental doom-saying that approached apocalyptic millenarianism surged underneath this sense of wonder and awe.

The biologist Paul Ehrlich, via his bestselling book The Population Bomb (1968) and in television appearances with Johnny Carson, forecasted that millions of people in deprived nations would be starving worldwide by the 1970s. Intimately connected with 1960s-era fears of uncontrollable population growth were alarmist predictions of a future marked by dwindling natural resources. Petroleum prices shot up and bureaucrats enacted new rules to govern a scarcity society. In the US, this meant gas rationing, year-round daylight saving time and national speed limits. The country appeared, as the cover of Newsweek put it in November 1973, to be ‘Running Out Of Everything’. Predictions of millions of people clamouring to enter the US, and a future marked by dwindling natural resources, were understood by many Americans as a potential menace to their way of life and their national security.

In response to the twin threats of economic and environmental danger, a distinct survivalist subculture emerged. A flurry of exclamatory books and pamphlets professed apocalypse soon. In his newsletter The Survivor, the author Kurt Saxon observed that ‘society is collapsing due to overpopulation, mental cripples, pollution, changing climate, and scarcity of resources’. In 1975, the former Green Beret Robert K Brown began publishing Soldier of Fortune magazine out of an office in Boulder, Colorado. It soon included articles about weapons, skills and products aimed at the militant survivalist community. By this point, Theodore Kaczynski had already moved to rural Montana, becoming a self-taught survivalist before finding infamy as the Unabomber.

The survivalists had a kind of cousin in the community of enthusiasts for sustainable living. This paisley-patterned social movement was catalysed and informed by publications such as the Foxfire books and, most famously, Steward Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog (1968-98). Hundreds of thousands of communards, tool freaks and ‘hippie modernists’ coalesced under their geodesic domes into a spectrum of back-to-the-land experiments by early 1970s. While the political ideologies of commune-dwellers differed from the survivalists, they too shared a distinct preoccupation with self-reliance and readiness.

Well before survival emerged as a dominant theme for the 1970s, a few professional artists were already attuned to existential threats lurking over the horizon. In San Diego, Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison reacted to the array of technological, economic and environmental challenges that marked the 1970s, and proposed solutions in response. Over careers that spanned more than five decades, the Harrisons made a series of artworks that functioned both as an early warning system for environmental catastrophe while also offering suggestions for surviving calamitous times.

Born in New York City in 1927 and 1932 respectively, Helen and Newton married in 1953 and arrived at the University of California, San Diego in 1967. Helen had studied education and psychology and worked in the school’s administration. Newton earned degrees in fine art from Yale, before being appointed a professor in the school’s visual arts department. Early in his career, he worked in sculptures and paintings. But the first Earth Day, held in April 1970, prompted the Harrisons to begin shifting into survival mode. ‘I want to know how I will survive,’ Newton said, ‘how we’ll all survive.’ Their growing fascination with local and global ecosystems drove their transition to a new kind of art-making and a new professional identity of working collaboratively as ‘the Harrisons’.

The existential fears that beset the Harrisons were shared by the small communities of survivalists who had taken to hoarding gold and guns in anticipation of societal collapse. But the Harrisons rejected a purely negative view of the future. ‘We took up the issue of survival,’ Helen later said, ‘and introduced utilitarianism.’ Here, they were, in their own self-directed way, following Brand’s suggestion that ‘when a species is in a bind’ the solution was to ‘multiply alternatives’. As Newton Harrison described: ‘I abandoned the concept of myself as an artist. I began to think of myself as a problem solver instead.’

Starting in 1970, the Harrisons executed and exhibited a series of projects they called Survival Pieces. The first of these installations – subtitled Hog Pasture – was commissioned by the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. It started with soil that Newton had handmade as a form of ecological ritual. This was used to fill a large planting bed over which they scattered a seed mixture labelled as ‘Annual Hog Pasture Mix’ purchased from a garden catalogue (thus giving the piece its name). Under overhead light boxes, their project grew quickly into a lush indoor pasture. However, when the Harrisons requested permission to include an actual pig with the work – Newton envisioned the installation as a ‘protein production site’ nourished by hog droppings – the museum staff refused. But visitors to the midwinter show still could enjoy the sensory input that Hog Pasture provided. ‘The pasture smelled delicious and was beautiful,’ Newton recalled. ‘People gathered around it in a circle.’

Hog Pasture marked a turn in the Harrisons’ thinking toward sustainable food production. ‘What if everything went away?’ Newton mused. ‘How would I survive? It was then I decided to become a farmer.’ They saw it as an alternative, and possible successor, to the modern supermarket, which ‘disrupts man’s intuitive contact with his biological sources’. Their new direction linked the Harrisons’ evolving artistic practice with both the pragmatic ‘back-to-the-land’ communards and the darker methods of the survivalists.

The result was a living ‘colour field’ painting akin to something Mark Rothko might have produced with paint

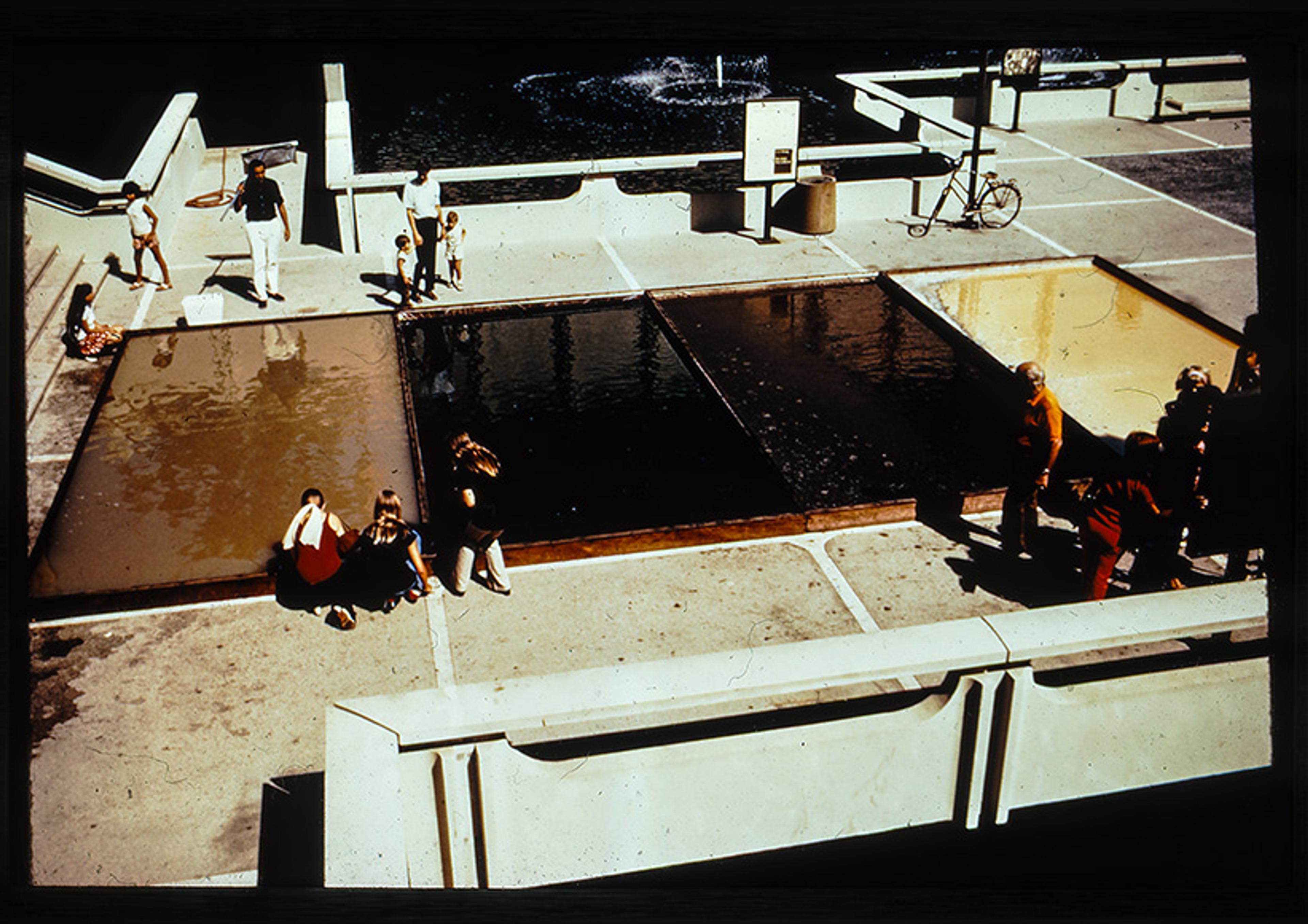

In 1971, in front of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), the Harrisons exhibited their second Survival Piece. Subtitled Notations on the Ecosystem of the Western Saltworks with the Inclusion of Brine Shrimp, it was inspired in part by their conversations with marine biologists at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego. Newton learned that certain species of algae would change colour as the salinity of the ambient water varied. At the same time, brine shrimp could exist with the algae in very salty water. With this knowledge – Helen, at this point, did much of the research while Newton tended to build their installations – the Harrisons created a shallow pond, divided into four 10 ft x 20 ft sections, each filled with water of varying salinity.

Survival Piece II: Notations on the Ecosystem of the Western Saltworks with the Inclusion of Brine Shrimp (1971), at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, California. The right pond is ready for salt harvest; the left pond, for brine shrimp harvest. Photo by Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison

There was some irony in that the Harrisons placed their installation between two similar ponds that LACMA staff rigorously treated with algae-killing chemicals. The Harrisons stocked their pond with home-grown algae and, as the carotene in the single-celled creatures varied, different colours emerged, ranging from blue-green to yellow-green to a brick-coloured red. The addition of brine shrimp, which ate the algae, altered the colours as well. The result was a living ‘colour field’ painting akin to something Mark Rothko might have produced with paint. To this they incorporated a twist drawn from conceptual art – when the exhibition was about to close, they allowed the water to evaporate, collected the salt, and then sold it at below-supermarket cost. And the brine shrimp? The Harrisons made a fish stew – by Newton’s candid account it tasted terrible – and, with the generous addition of capers and anchovies, a spread they put on crackers and shared with compliant guests.

Dinner at the Hayward Gallery, London 1971. Photo by Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison

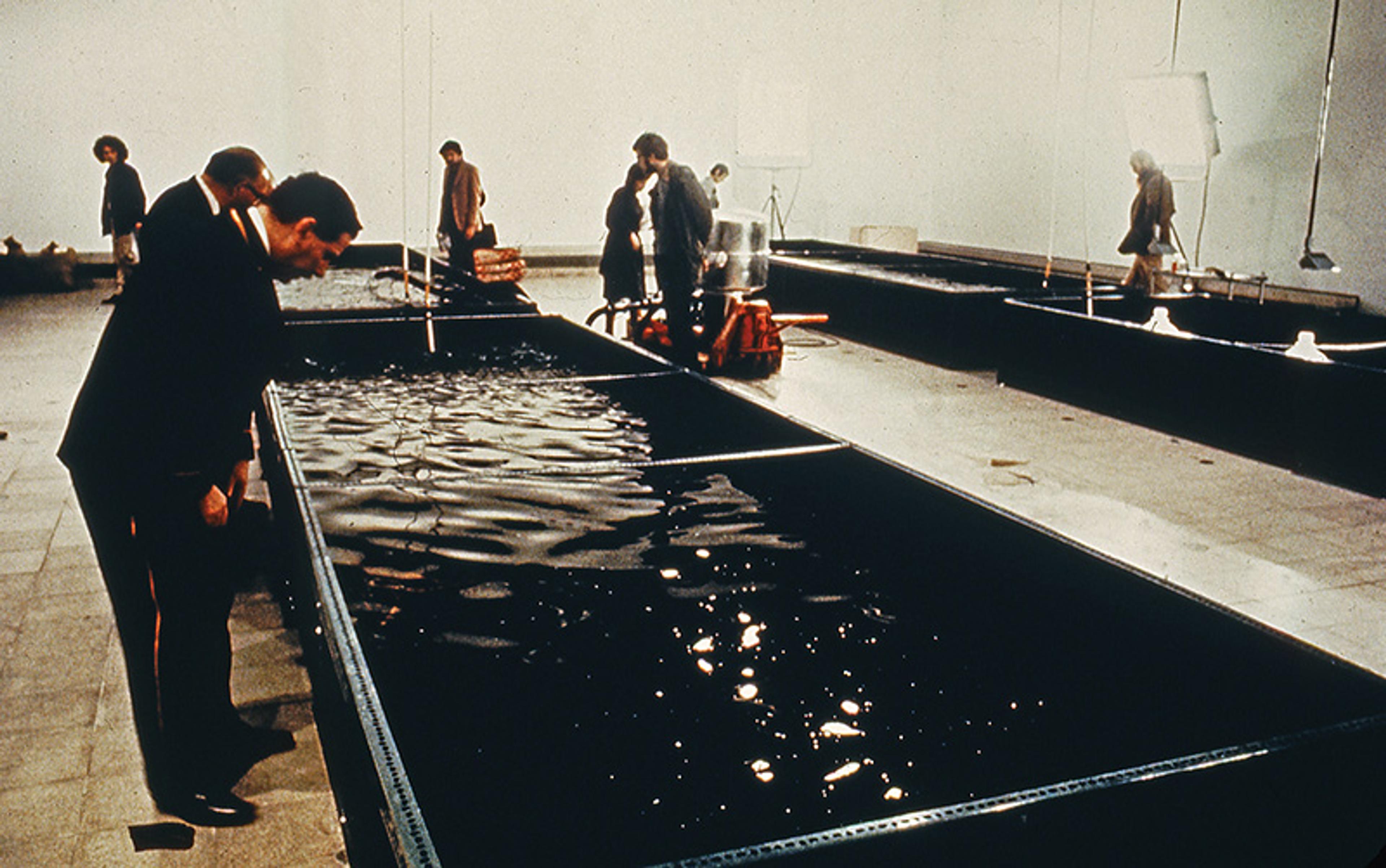

About six months later, the Harrisons exhibited their third Survival Piece, titled Portable Fish Farm. Created for the show ‘11 Los Angeles Artists’ at the Hayward Gallery in London, the installation used catfish as the basis for a sustainable food-producing system. Newton Harrison began with a series of detailed schematic drawings of the sort one might find in the pages of Popular Mechanics (or survivalist newsletters). These laid out the designs for six large rubber-lined tanks, three of which would hold catfish in various stages of development, from fry to fingerlings to mating size, bringing the whole cycle full-circle. Another tank would hold brine shrimp and algae, while oysters and lobster would be raised in the remaining two tanks. In keeping with the Harrisons’ focus on ritual – and following the tradition of conceptual art – their proposal also contained detailed instructions for preparing a series of meals, including bouillabaisse and zuppa di mare, for up to 250 gallery visitors. As Newton recalled, the piece was ‘actually about backyard farming … to bring into everyday life, fish farming as a protein source’. But it also added social commentary as an ingredient, serving bottom-feeding fish ‘to the elite and (sometimes) noble British art public!’

Survival Piece III: Portable Fish Farm (1971), Hayward Gallery, London. Photo anonymous

However, what caught the attention of the British art world – and brought the Harrisons their first major burst of international notoriety – was their inclusion of a seventh tank where catfish would be killed via electrocution before being eaten (and their entrails subsequently fed to the lobsters to emphasise the sustainability of the work). As the artists learned, small catfish were often sold as pets to British aquarium aficionados, while electrocution was seen as a barbaric and all-too-American punishment. British newspapers ran a flurry of articles about the controversy cooked up by the Harrisons’ art installation, and the comedian Spike Milligan, who championed environmental causes, broke a window of the Hayward. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals also protested vocally, despite explanations that electrocution was a quick and common method to dispatch catfish. (Newton had adopted the method after catfish farmers in southeastern California had taught him how to grow, breed, kill and gut the fish efficiently.)

Meanwhile the Harrisons repeatedly appeared on British radio and television to explain their work. They noted that killing catfish was just one part of an artwork devoted to showing a particular system for survival. ‘Each of [our] works is becoming a prototype,’ Newton Harrison said, ‘an analogue for a natural system.’ As Newton recalled, it seemed odd to be upset over the ethics of killing some catfish in an art gallery when millions of animals were regularly slaughtered and eaten in Britain. Instead, he redirected conversations toward the ‘unethical implications of [his] country’s behaviour in Vietnam’.

The controversy over Portable Fish Farm continued right up to the show’s opening date (scheduled for September 1971), and overshadowed the other artists whose works were also on display. Two reporters standing outside the gallery were overheard debating whether electrocution or hanging was the preferred means for killing a fish. ‘But you can’t really hang a fish, can you?’ one of them asked, ending the discussion. Then, just a few hours before the gallery was to open, the Arts Council chairman Arnold Goodman inspected the show and warned that they could shut down funding. In response, Maurice Tuchman and Jane Livingston, the LACMA curators who put the show together, essentially said: ‘No fish. No show,’ while the Harrisons protested the attempt at censorship. The museum’s directors briefly delayed the opening, and the whole situation wasn’t resolved until the next evening. By then, the Harrisons had generated support from the geneticist and Nobel laureate Maurice Wilkins who, in turn, enlisted the Arts Council member C P Snow. The author of The Two Cultures (1959) decreed that the Harrisons’ work illustrated the sort of links between science and the humanities that he had long championed. In the end, the show proceeded as planned only after the Harrisons agreed to not kill any catfish in view of the public.

The international attention generated by Survival Piece III: Portable Fish Farm provoked enduring introspection and assessment from art critics. To start with, the Harrisons were hard to place, both geographically and categorically. Like today, the general perception was that Manhattan remained the centre of the art world. But the Harrisons were based in self-contained San Diego, about as far away from Gotham as one could get, and relatively isolated by mountains, desert and the Mexican border. Geography as well as the city’s innate political conservatism – defence industries and military bases were an important part of the regional economy – set the Harrisons’ working environment apart from the ‘hippie modernism’ that characterised West Coast art in the US. Moreover, their work was neither detached nor cool in the manner of many southern California artists who were part of the ‘light and space’ and ‘finish fetish’ movements. Rather, it engaged with and confronted societal needs and ecological peril. Their work was also more dialogic and didactic in nature, running counter to the object-oriented preferences of many art critics. Finally, the Harrisons were based at a large and growing top-tier university that prioritised science research. Similarly, their art practice – what one critic branded ‘The Image Maker as Eco Freak’ – was research intensive. Their secure university positions meant that they could afford to work outside the gallery and museum complex.

One of the first questions critics asked – one encountered by many conceptual artists whose work was as much about ideas as it was about object-making – was what sort of art the Harrisons made. Their focus on ecology prompted some critics to categorise them, at least early in their careers, as part of the Land Art movement. But the Harrisons’ work was strikingly different in scale and method from monumental works in the genre, such as Michael Heizer’s Double Negative (1969) or Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970). ‘Think of the vast energy that goes into big cuts and shapes in the desert,’ Newton said in 1980. ‘They are transactional with museum space, not with the Earth.’ Moving hundreds of thousands of tons of earth and rock via bulldozers might entail modifying the environment, in other words, but it by no means revealed deep ecological relationships.

Their projections of the present into the future are morality tales about who will survive (and how)

Another attempt to understand the Harrisons’ work situated them alongside conceptual artists interested in ‘dematerialising’ the art object, an assessment that they accepted to a degree. For conceptual artists such as Sol LeWitt, the finished ‘product’ might just be the artist’s ideas for the piece, perhaps preserved in accompanying documentation, rather than a discrete objet d’art that could be displayed and sold in a gallery. Here, critics could appeal to the tradition of the Dadaist Marcel Duchamp whose displayed and labelled urinals and bicycle wheels prodded viewers to think about what art was. According to one art writer, the Harrisons functioned likewise, provoking viewers into thinking about what they would need to survive impending ecological collapse. In response to the oft-asked question ‘Is it art or science?’ Newton Harrison countered: ‘When you read Dostoyevsky, why aren’t you calling it social science?’ The Russian novelist took ‘transactions with the world and transposed them into images and stories. We do the same. The best description we can make of ourselves is as storytellers of a sort.’

However, the Harrisons’ emphasis on dialogue and storytelling closely paralleled one of the characteristic traits of the fringe survivalist movement. This community’s literature abounds with stories about how society collapsed, and provided a necessary prelude to detailed narratives about how prepared individuals kept themselves and their loved ones alive. As the sociologist Richard G Mitchell noted after his participant-observation studies of survivalists and preppers, the heart of their endeavours is ‘constructing “what if” scenarios in which survival preparations will at once become necessary and sufficient’. Creative and artful in their own grim way, these ‘survival scenarios’ are, Mitchell wrote in Dancing at Armageddon (2001), ‘akin to contemporary legends told in future tense’. In a sense, their projections of the present into the future are morality tales about who will survive (and how) a coming catastrophe caused by nuclear war, economic collapse, communism or natural disaster.

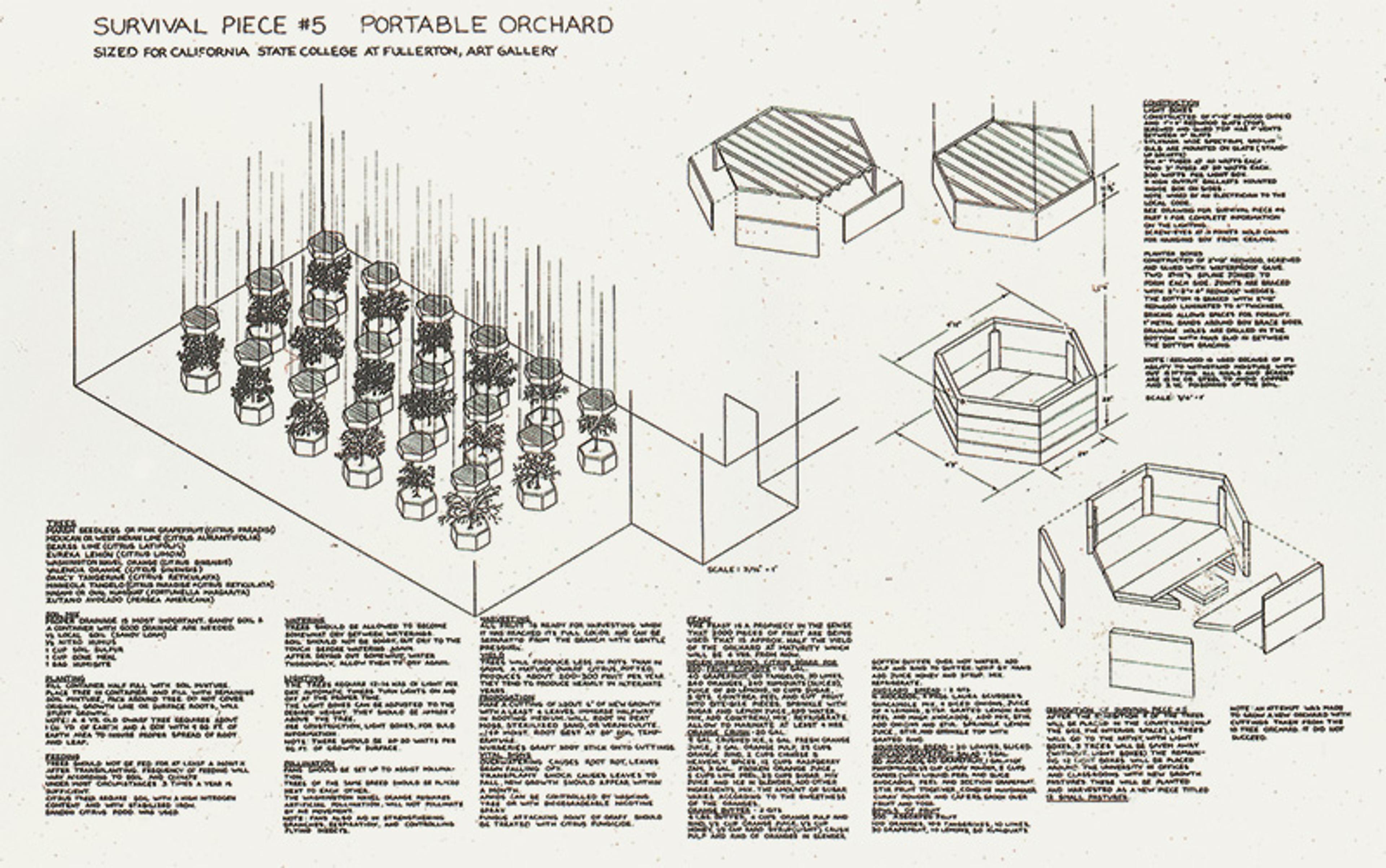

Sketch for Survival Piece V: Portable Orchard (1972), at California State University, Fullerton. Courtesy the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

The Harrisons deliberately aligned their art-making with a similar focus on preparedness. By 1974, they had made seven installations in the Survival Pieces series. Works such as Portable Fish Farm and Portable Orchard (1972) were created, the Harrisons said, to offer people ‘a self-sufficient survival resource’. Their blend of research, art-making and storytelling was predicated on fears about the future, aimed ‘to teach lessons about survival in an ecologically blighted world’. But they also contained seeds of hope for averting undesirable futures.

After the Survival Pieces series, the Harrisons grounded their artworks even more deeply in narrative and storytelling. The best example of this is their monumental installation The Lagoon Cycle. Conceived and created over a decade (1974-84), this seven-part epic – it is 360 ft long and 8 ft tall – is organised as a dialogue between two characters, ‘the Lagoon Maker’ and ‘the Witness’. The former, a devotee of technological solutions infused with hubris, proposes increasingly elaborate ways to carry out sustainable food production – what if the Salton Sea in southern California could be reclaimed, its pollution sent to the Pacific Ocean, and used as a large-scale fish farm? The Witness, in turn, reacts to these schemes, encouraging their partner to stop thinking like a technocrat and consider the real-world ecological effects of their schemes. The cycle’s final part, titled The Seventh Lagoon – The Ring of Fire the Ring of Water (1984), ends with a map of the world, its coastlines now underwater. The Witness asks of their partner:

and in this new beginning

this continuously rebeginning

will you feed me when my lands can

no longer produce?

and will I house you

when your lands are covered with

water?

and together

we will withdraw

as the waters rise

From The Lagoon Cycle, The Seventh Lagoon – The Ring of Fire the Ring of Water. Photo by Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison

If we stereotype science as the pursuit of truth, and art as the pursuit of beauty, how should we situate the Harrisons and other eco-artists? One role of art is helping us detect and perhaps reconcile ourselves to awkward truths – that our existence as a species on the planet is not certain, nor are its resources infinite. By now, it is clear that the deniers of climate change or pandemics will be swayed by neither facts nor scenes of worldly devastation and suffering. It is here that artists can assume a more prominent and vital role.

Like science, art helps us make sense of the world. But rather than telling us, as science does, what is – at this point, the basic facts regarding the reality of climate change are beyond dispute – art can help reveal what could be. The Harrisons’ art certainly depicted the grim possibilities of a future changed world. But they also contained a sense that positive change remained an option even if this was just, as the German historian Christof Mauch phrased it here, a ‘slow hope’. The Harrisons used their artworks to tell stories about the future but also to suggest paths of action. They believed that their art could function as a pragmatic tool for survival. Seen this way, art offers another avenue, outside the realm of scientific models and meteorological data, to show people the world as they haven’t seen it before, and to reveal scenarios of a changed planet and an altered future. In this future, we will all have to become survival artists.