In the 1st century CE, Boudica, warrior queen of the Iceni people, led an army of 100,000 to victory against the mighty Roman Empire. So complete were Boudica’s triumphs that Rome was in danger of losing control of her province. Riding high on a war chariot, daughters behind her, she led her Britons in a vengeful fight for freedom. But what did freedom mean for an Iron Age queen and her people, and what were its limitations under empire?

To appreciate Boudica’s place in the Roman world, it is necessary to understand something about ancient misogyny. The Romans viewed women warriors as indicative of an immoral, uncivilised society, and this attitude helped to rationalise their subjugation of other peoples. Nevertheless, these women became legends.

Ancient Rome prided itself on the power of its patriarchy, and was quick to condemn women who broke boundaries and encroached upon the rights, privileges and positions of power held by men. The voices of these women were silenced, their stories transmitted by men, their characters exaggerated for literary effect. Juvenal, for example, composed an entire satire devoted to denigrating women. Considering female gladiators, he asks: ‘How can a woman who wears a helmet be chaste? She’s denying her sex, and likes a man’s strength.’ Juvenal blames luxury and riches, the ‘evils of a long peace’, for producing such ‘monsters’, women who adopt male roles. Juvenal’s label reveals a deep-seated fear of female power and autonomy that permeated Roman society.

In imperial Rome, law, family and society combined to restrict a woman’s participation in public life, based on traditional morality and an understanding of what was best for members of a sex considered weak and unwarlike by nature. Women who appeared in military situations were anomalous in this system, although exceptions did occur. In the early days of Rome, the legendary Sabine women rushed on to the battlefield between the Romans and Sabines, demanding peace between their husbands and blood relatives. These women were successful because they acted on behalf of their families, without taking up arms. By contrast, in the early 1st century CE, Agrippina the Elder, a member of the ruling family, was severely criticised for taking on the responsibilities of a general in supporting her husband Germanicus’ retreating troops. Plancina, Agrippina’s contemporary, broke the bounds of female decorum by observing the practice exercises of her husband Piso’s cavalry. The Roman senate even debated whether women should be allowed to join their husbands on provincial governorships. What if they became more powerful than their husbands in the home, the forum and the army?

Women warriors epitomised these fears. Legends of the Amazons proliferated in the ancient world – women warriors of the Steppe who travelled on horseback and cut off one breast so that they were not impeded from drawing back their bows. Penthesilea, queen of the Amazons, led her women into the midst of the Trojan War, and was admired by Achilles for her ferocity: he sought her out in battle, and even at the moment of her death, their eyes met and he fell in love. Thus sexuality and the warrior woman became intertwined. The pattern persists in Roman literature.

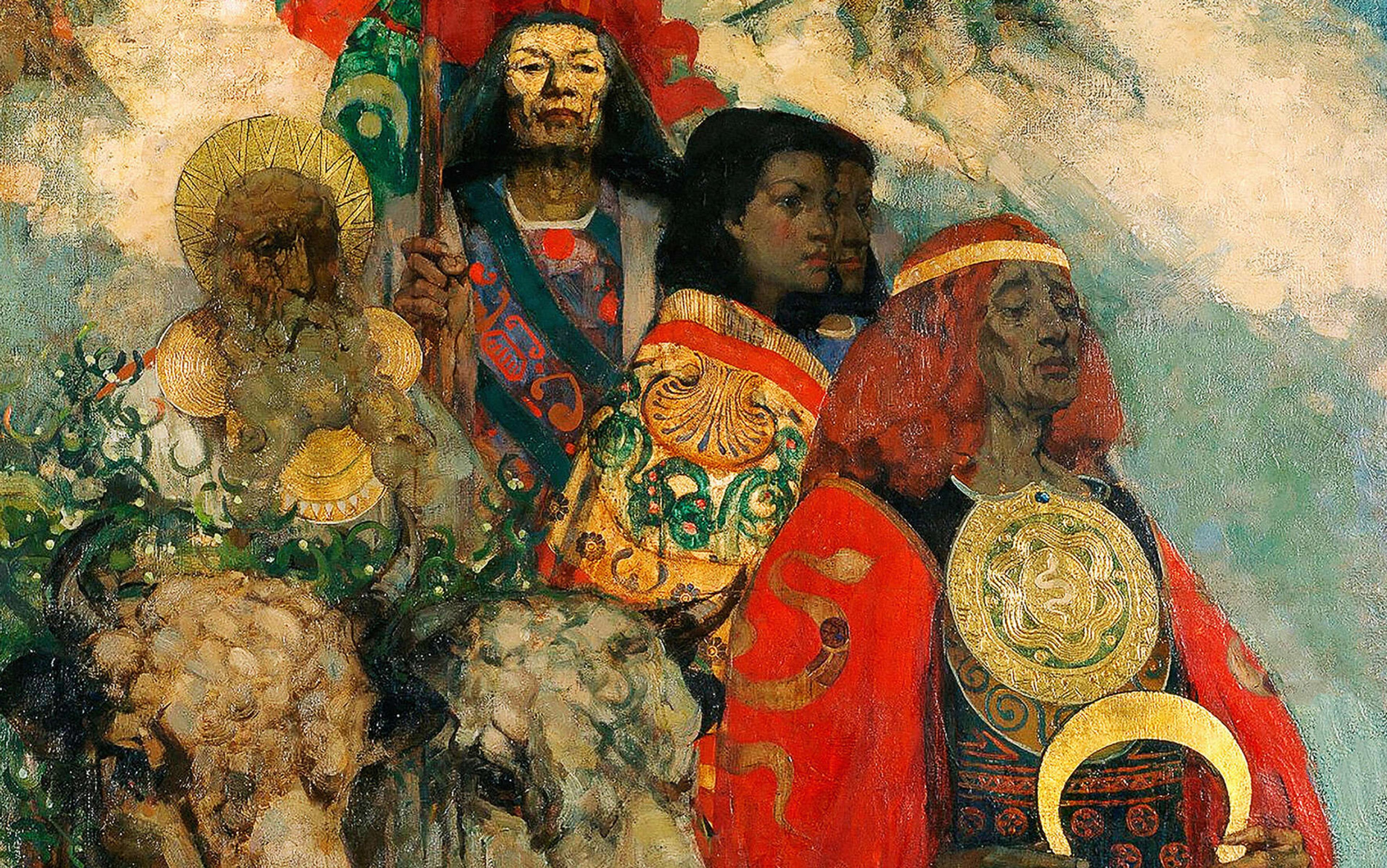

Dido of Carthage, Cleopatra of Egypt and Boudica of Britain all held positions of power that were not limited on the basis of sex. Paradoxically, Roman authors used their stories as evidence of innate female weakness and an inability to lead. Literary portraits connect these women’s sexuality to poor leadership skills. In Virgil’s Aeneid, Dido commits suicide over her obsession with Aeneas. Virgil’s contemporaries, the poets Propertius and Horace, denounced Cleopatra as a ‘whore, queen of incestuous Canopus’, and a ‘deadly monster’ drunk on wine, who enslaved Marc Antony through her cunning and irresistible charm. Images of such women minimised their ability to lead through sexualising the female form, including a personified Britannia cowering from the emperor Claudius. The representation of a province as a sexualised, dominated female body is common in monuments and on Roman coinage. In triumphal imagery large and small, a man’s domination over a woman’s body becomes analogous to Rome’s expansion of her empire and control over provinces and peoples.

Boudica (also spelled Boadicea or Boudicca), queen of the Iceni in Britain, provides a case study for the reception of women warriors. She encapsulated the idea of the warrior queen from the time of her revolt in the 1st century, and maintains a towering presence today. Boudica survives in the accounts of two Roman historians: Tacitus, writing in the late 1st and early 2nd century CE, and Cassius Dio, writing a century later. The authors differ in their details, but agree that Boudica unified the Britons as never before and led a revolt against the Romans in 60/61 CE. Her story creates a parallel between different views of gender equality held by the Romans and the Britons, and the dichotomies of empire and colony, power and subjugation. Boudica’s name means ‘Victory’ – but what exactly did she win?

In the Roman accounts, Boudica fought for freedom from the Romans, a colonial oppressor she viewed as greedy and immoral. According to Tacitus, after the death of her husband, the client king Prasutagus, Boudica’s life took a dark turn. The Romans beat her and assaulted her daughters. They enslaved her relatives and confiscated Prasutagus’ land and ancestral wealth. Boudica’s motivations for revenge are personal, but her experiences provide a case study for the broader impact of Roman imperial expansion.

At the time of her revolt, Boudica’s Iceni were allies of the Romans, but did not engage in the same level of trade as other tribes in southeastern Britain. No urban centre existed in East Anglia, the area occupied by the Iceni, and archaeological evidence suggests a conformity with Iron Age expectations. Families lived in settlements of thatched timber roundhouses, not towns, and upheld an agricultural economy. Hoards of gold, silver and electrum jewellery and other items attest to their wealth, including hundreds of torcs, intricate neck rings that were markers of wealth or status; ritual deposits of this material were buried at sites of religious importance. The Iceni had their own coinage, and did not use many imported goods. Thus they were able to remain separate from the political, social and commercial activities of Roman towns and colonial settlements that cropped up in Britain after the Roman invasion of 43 CE. Their unfortified homes and decentralised areas of occupation were ripe for plunder by the invading army.

Gender expectations and social strata among Boudica’s society are not neatly defined by the ancient material. Nevertheless, it is clear that the Roman occupation questioned the authority of her family and their local position of power. Boudica’s motherhood was key to her success. Her response to the Romans followed a primal instinct to avenge her daughters. However, her call to action instigated uncontrolled violence on the part of her army, initiating a vengeful response by the Romans that endangered all Britons. The actions of her army were used in part to justify the need for Roman control.

In spreading their empire, the Romans also aimed to transform those perceived as barbarians into complacent subjects. Tacitus outlines this process in his biography of his father-in-law, Agricola, who served as governor of Britain from 77-84 CE. Agricola urged the Britons to build temples, public spaces and homes, thereby making a people formerly ‘scattered and barbarous and therefore inclined to war’ accustomed ‘to rest and repose through the charms of luxury’. The Britons also learned to desire the eloquence of Latin, to wear the toga, and to receive Roman citizenship, but were drawn to the vices of the bath and fine dining. Tacitus concludes that this acculturation was part of their servitude.

In the film Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979), Reg ponders: ‘They’ve taken everything we had … And what have they ever given us in return?’ The response – sanitation, medicine, roads, fresh water, baths, education – lists just some of the Roman Empire’s contributions to European society. But the question of servitude remains: the Romans took their dues in taxes and lives, and engineered the environment to become Roman. This imperial agenda met with particular resistance from those whose positions in society were eliminated, including Boudica, the warrior queen.

Progressive as a female leader, she is retrogressive in her desire to remain separate from Roman civilisation

Had Boudica accepted Roman rule and altered her life to suit that of her conquerors, she might have been recognised after death for her more conventional qualities. An honorific epitaph for Boudica in Roman terms would have been composed following a formula based on a Roman understanding of normative gender roles: she would have been identified in relation to a man (wife of Prasutagus), noted for her success as a mother (she bore two children), and praised for her domestic virtues (for example, that she kept house and made wool). As a figure of resistance, she requires a different memorial.

Boudica revolted in the generation before Agricola arrived in Britain. Her ancient portrait brings attention to questions of gender and power in the ancient world, as well as the impact of a colonial power on her subjects. After suffering at the hands of the Romans, Boudica united the Britons and took her revenge. While the Roman general Suetonius Paulinus was away in Wales, attacking the Druidic centre at Mona (Anglesey), Boudica formed her army. Thousands of Britons marched towards the Roman provincial capital at Camulodunum (Colchester) and burned it to the ground, before advancing on Londinium (London) and Verulamium (St Albans). They tortured their prisoners and took no spoils, perhaps aware that their victory would be short-lived. On their return from Mona, Suetonius Paulinus and his well-trained Romans defeated the Britons in a single pitched battle, and Boudica’s Iceni never recovered.

Boudica’s actions as a warrior are left to the imagination, as Tacitus attributes the destruction to a universalised ‘Briton’. Boudica’s impact is visible as she rallies her army. Before the final battle, she speaks to her warriors, using her personal injury to galvanise an entire people to action. As one woman among many, she calls for justice on behalf of all those assaulted by the Romans. She asserts that it is British custom to fight under a female leader, and proclaims the necessity to win or die trying. Even the gods are on their side, so how could they lose? Despite her exhortation, the Romans win handily, and Boudica commits suicide rather than allow herself to be taken prisoner. Her courage in death is admirable. Like Cleopatra, she would rather die than be paraded in a Roman triumph.

Dio, on the other hand, revels in Boudica’s Amazonian qualities. His Boudica is superlatively tall and terrifying to behold. She wears the golden torc of a regent and the multicoloured tunic of a Briton. Her eyes glance fiercely, and hair the colour of a lion’s mane falls down to her hips. She grasps a spear to address her troops, instilling awe in all. In her speech, she condemns the Romans for oppressing the Britons through excessive taxes. She feminises the Romans as weak and unequal to the harsh weather and rough terrain of Britain, while celebrating her society as enduring and hardy. Her people know no gender distinctions: men and women in Britain share everything in common, including glory on the battlefield. Furthermore, she celebrates Britain’s separateness: her people are ‘so separated by the ocean from all the rest of mankind that we have been believed to dwell on a different earth and under a different sky’. After their initial victories, her army treats their captives with unspeakable cruelty, impaling the noblewomen on stakes, all in the name of a goddess of Victory. When Boudica dies, the Britons honour her with a magnificent burial and disperse, regarding themselves as defeated.

In her speeches, Boudica juxtaposes Roman avarice with British freedom. She uses the promise of freedom as a motivating factor, but what does this mean? Both Tacitus and Dio took a conventional term from Roman political thought and applied it to a situation they did not participate in or even witness. Both fail to consider how Boudica’s followers would have defined freedom or how it would have looked to someone living in her society. In part, this failure is the point. Tacitus and Dio depict a Boudica who desires autonomy from Rome. Her situation can be generalised as a fight for freedom from a tyrannical force. Both authors survived the regimes of tyrannical emperors to enjoy times in which the freedom of speech existed once more.

Boudica seeks freedom from persecution and the changes forced upon her and her Britons by a colonial power. She thus presents a problem for the idea of progress. She is a progressive figure from a modern perspective, as a female political and military leader, but retrogressive in her desire to remain separate from the Romans and their conceptions of civilisation and urban development. Her celebration of the lifestyle of the Britons includes gender equality and the opportunity to share equally in valour, but such equality would require a return to the Iron Age.

Despite her powerful words, Boudica failed as a military leader. Her army was defeated in a single battle and her people slaughtered. Her revolt did not have a lasting impact or limit the Roman presence in Britain (rather, the opposite occurred), yet it left a long and varied cultural legacy. Boudica has been mythologised, redefined and pressed into service to suit varying contexts, held up as an imperial icon, guardian of national identity, and champion of women.

Her reception has been generally positive, although inconsistent. Readers might weep for her and her daughters, admire her ability to unify the Britons, and sympathise with the desire to oppose any foreign power. However, they also remonstrate the violence of her army’s revenge – is this lawlessness the result of too much freedom? Still, Boudica reminds audiences of their own struggles. She has been used to make various points about contemporary society, and inserted in discussions of gender, race and power, as well as in debates about Britain’s relationship with the rest of Europe.

Boudica could hardly have imagined her story to last for millennia, nor would she have recognised herself as a harbinger of the British Empire, a figure of nationalism, a symbol for suffragists or a supporter of Brexit. British queens and female politicians have adapted her warrior identity. Elizabeth I was compared with the outspoken warrior, and Queen Victoria embraced her as a precursor, a Celtic Victoria. In the 20th century, Margaret Thatcher was known as a political battleaxe, a ‘Boadicea in pearls’. More recently, Theresa May has become the ‘Brexit Boadicea’. Boudica’s resistance to the Romans is recast as removal from the EU, her defeat overlooked by Brexit supporters. This autumn, her story plays out on the stage of Shakespeare’s Globe in the form of Tristan Bernays’s play Boudica, perhaps warning against ‘the danger of splenetic isolation’.

In the US, Boudica has a place at a different table. In the 1970s, she became part of Judy Chicago’s installation The Dinner Party, now the centrepiece of the Elizabeth A Sackler Center for Feminist Art in the Brooklyn Museum. As one of 39 guests, Boudica is seated among women from the Primordial Goddess through to the artist Georgia O’Keeffe. Her place setting utilises Celtic imagery adapted from 1st-century evidence; her presence marks her as a feminist icon.

Boudica continues to fill a cultural need, and her story has especial relevance for today’s ‘women warriors’, those fighting for gender equality throughout the world. This includes women engaged in the struggle for equal opportunities in politics and the academy, in Title IX cases and the #MeToo and Time’s Up movements. Boudica’s reception allows us to broaden our perspective on the concept of freedom, particularly regarding gender bias and cultural conformity. Although their battlefields are different, the message of these women remains. Freedom means that women are able to live without fear of persecution on the basis of sex. There will continue to be Boudicas as long as women continue to test and redefine the limits of this freedom, until such limits cease to exist.