In the mid-1990s, a novel wedding tradition became popular among African Americans: ‘jumping the broom’. As the couple is pronounced legally wed, they turn to the crowd, clasp hands and jump over a broomstick placed on the floor. One couple explained the ritual’s attraction. ‘It’s traditional,’ they said, ‘and we need to bring it back to our culture. Every Black person should do it.’ For them, as for many, culture and tradition were intimately linked to group identity, and jumping the broom symbolised racial and ethnic unity among those descended from enslaved people in the United States. Indeed, couples who did not jump the broom prior to its widespread revival often expressed regret that they were unaware of the custom when planning their wedding.

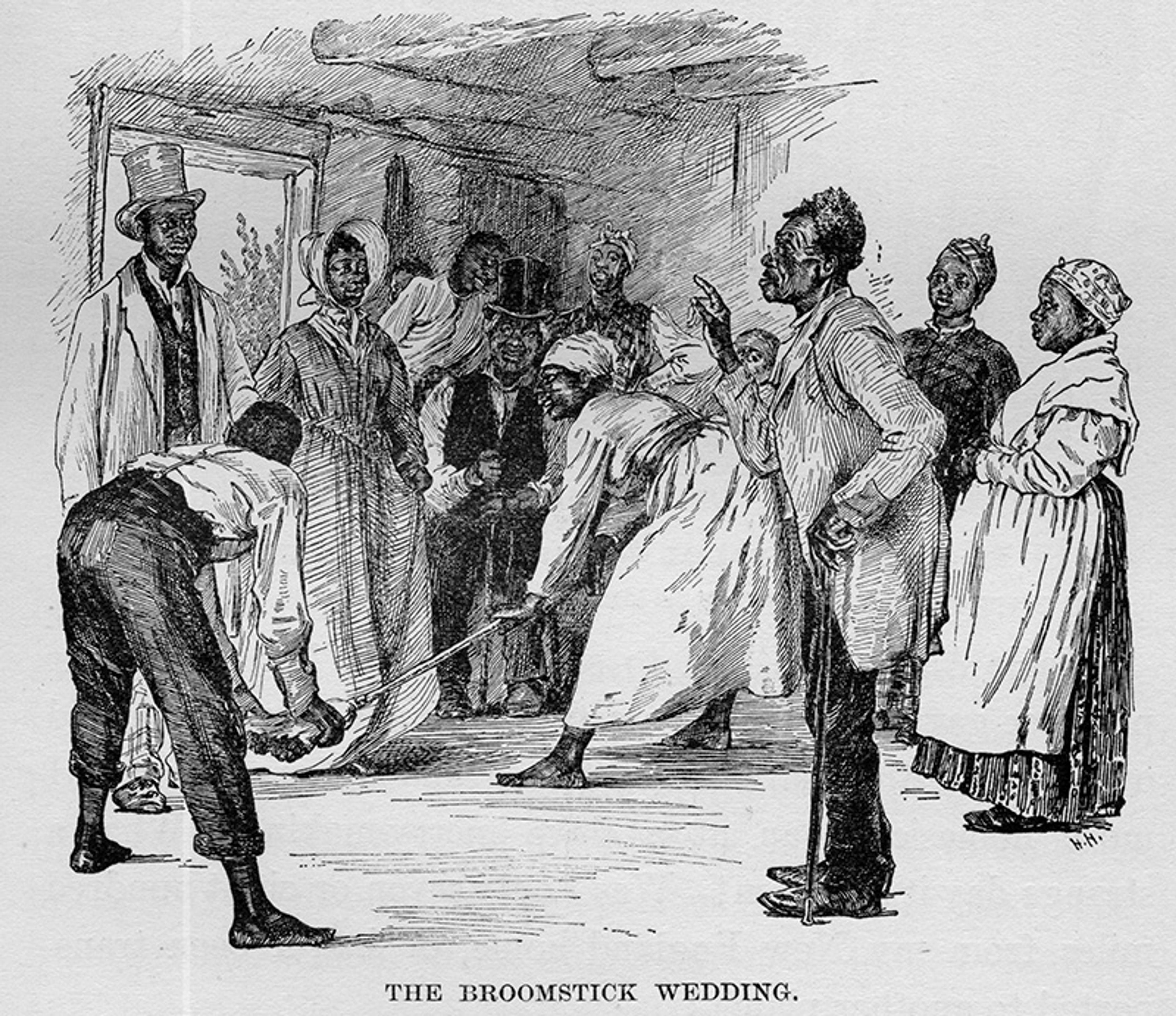

‘The Broomstick Wedding’ (1840s) from My Life (1897) by Mary Ashton Rice Livermore. Image courtesy slaveryimages.org

Rooted in American slavery, the ritual was often dismissed by the formerly enslaved shortly after the American Civil War. Many Black couples renounced it in the post-bellum period, seeing it as a vestige of slavery. Knowledge of the tradition waned until 1977, when it was reintroduced through the Roots television miniseries, which featured a broomstick wedding performed by an enslaved couple: the protagonist Kunta Kinte and his wife Bell. Then, in 1993, Harriette Cole’s book Jumping the Broom: The African-American Wedding Planner was published, which spurred mass embrace. Cole argued that the broomstick wedding was used by enslaved couples to reclaim dignity within a system that denied them legally recognised marriage. She speculated on attachments to African cultural beliefs about brooms, providing an origin story that highlighted the ingenuity of enslaved people who retained elements of their African heritage.

Then there was the pushback. Not everyone was thrilled about reviving a ‘slave-era’ ritual. Afrocentric leaders such as Maulana Karenga criticised Black couples who used it, arguing that it didn’t originate in Africa, but was actually introduced by slave owners. Jumping the broom, he asserted, reduced a couple’s commitment to one another because they performed the act ‘over an instrument of labour’. Did enslaved people take the ritual from slaveowners, as Karenga suggests? Or is it a celebratory innovation developed by enslaved Africans under extraordinary circumstances? As with the history of many rituals, how it came to be is far more complicated than it might seem.

Different renditions of jumping the broom exist in both historical and contemporary accounts: the broom can be held by guests, the couple can jump backwards or jumpers can alternate their leaps, and so on. But the custom called ‘jumping the broom’ follows a similar process among its various practitioners – and its practitioners are various indeed. Though associated with African Americans, the custom actually has historical ties to many communities, who, on the surface, seem to have little in common with each other. If one journeyed to the Appalachian Mountains of Kentucky in the early 1900s, one might have heard residents talking about a marital practice called ‘jumping over the broomstick’, which they believed to be unique to their own community. In Louisiana, marrying Cajuns called their broomstick wedding ‘sauter l’balai’. And across the Atlantic, communities throughout North Wales used the phrase ‘priodas coes ysgub’ to describe their own broomstick marriages in the 19th century. In 18th-century England, some authors even mocked their Scottish opponents by declaring that such a ceremony was simply a ‘Scotch wedding’. A similar ritual was popular among British ‘gypsies’, an ethnic group of Romani travellers ostracised within the British body politic. From the plantations of the Old South to the swamps of Louisiana to the smooth, green hills of Wales, one could find couples who announced their love and their commitment to one another by jumping over a broom.

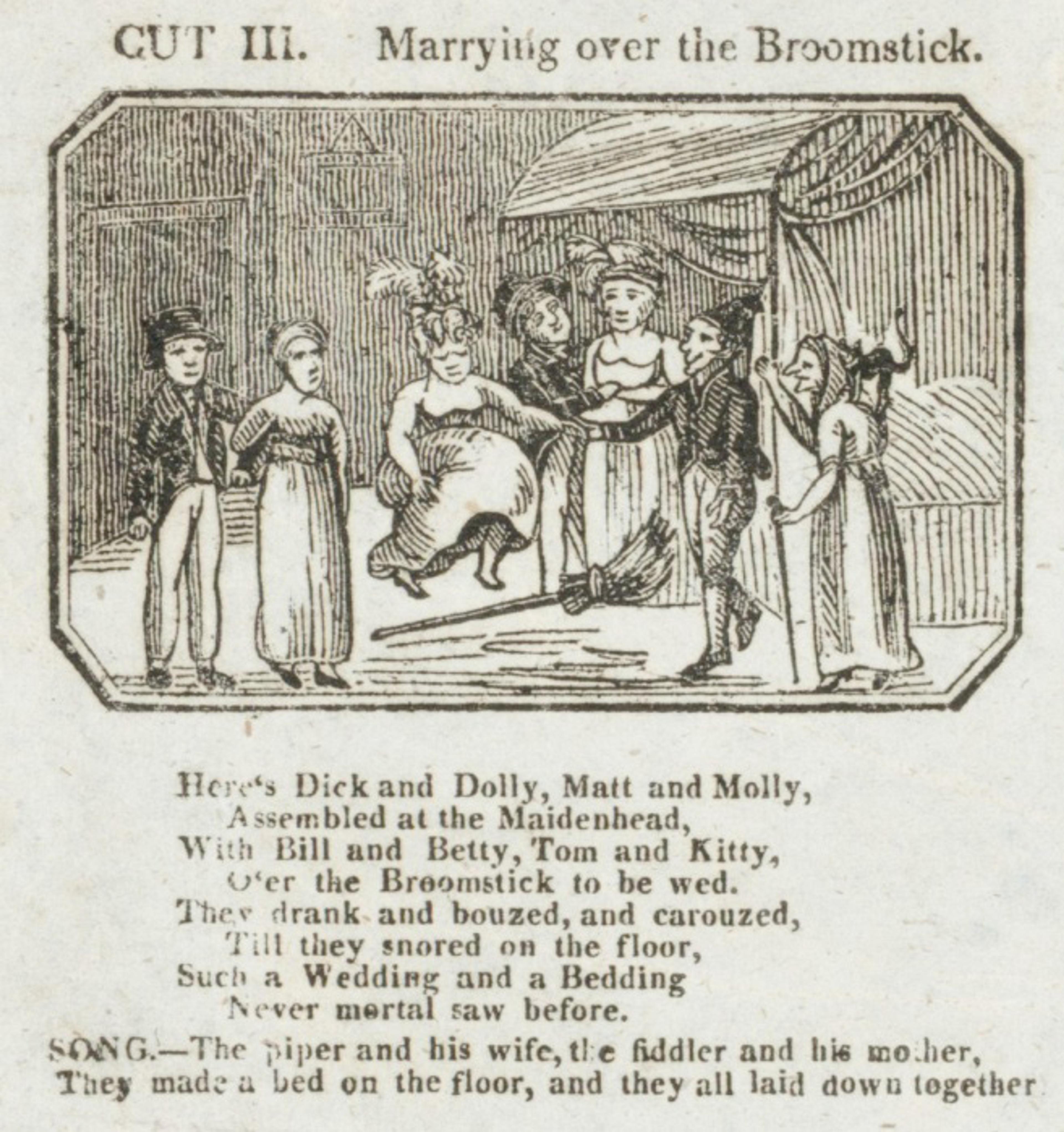

From The Marriage Act Displayed in Cuts and Verse (1822) by James Catnach. Courtesy the Walpole Library, Yale University

The broomstick wedding, in all its varieties, has often been viewed in opposition to the Christian wedding, causing its practitioners to be the target of scorn among those hoping to preserve matrimonial orthodoxy. Critics of the broomstick wedding – overwhelmingly represented by societal elites on both sides of the Atlantic – claimed it was an inferior and immoral representation of the marital covenant, and found it no surprise that it was used among marginalised people. Though such criticisms were full of ethnocentrism and classism, the critics were correct in one respect: the broomstick wedding was largely embraced by oppressed groups and those who lived on the margins of society. It provided them with a ceremonial process for securing their marital bond when few other options were available to their communities.

What else did its practitioners have in common? They were all members of what is today commonly referred to as the ‘Atlantic world’, a term used to describe how western Africa, western Europe and the Americas became linked during the early modern era through unprecedented rates of transoceanic travel. Historians have employed the ‘Atlantic world’ concept for decades, hoping to subvert the overemphasis on the nation state and show how the economies and peoples of apparently disparate countries and colonies were actually interconnected by transoceanic trading systems. The Atlantic world was produced and amplified through the transatlantic slave trade and the colonisation of the Americas, forever changing the landscapes of western Africa, western Europe, the Caribbean, South America and North America. Scholars of the African diaspora argue that a ‘Black Atlantic’ is a particularly relevant concept for understanding cultural developments throughout the western hemisphere.

Why jump a broom for matrimony? Why jump anything at all?

Forcibly taken from their homelands to labour as enslaved captives in the burgeoning plantation colonies, West Africans accounted for four of every five people who migrated to the Americas from the 16th century to 1820. This forced migration has a lasting legacy on the cultural, political and economic developments of each country tied to Black chattel slavery. Every country connected to the Atlantic slave trade owes much of its cultural dynamism to people of African descent, even if enslaved Black people made up a minority of the population as in the US. Despite the brutal conditions of chattel slavery, the West African people carved out their unique cultural identities through their interactions with Europeans and the Indigenous peoples already inhabiting the Americas. The cultural exchange impacted every facet of life for people of African and European descent, especially those born in the Americas.

It is in the broad context of the Atlantic world that we need to locate broomstick weddings. The ritual has a similar cultural genealogy to most customs of this era, in that it influenced multiple communities on both sides of the Atlantic, many of whom appear to have had no previous cultural attachments to the ritual. First documented most prominently among ostracised and marginalised people throughout the British Isles, the broomstick custom is a product of this Atlantic exchange, in which it was brought to a new location, acquired by different communities and reimagined by them according to their unique needs. Even when groups appear isolated or entirely disconnected from one another – such as white Appalachians and Louisiana Cajuns, or English labourers and the British Romani – we find similarities in their reasons for using the custom and in how they practised it, fracturing the imagined cultural borders that are often assumed to divide different groups.

All iterations of the ritual shared its most important feature: the actual jump over a literal broom, which signalled the ceremony’s completion. Is there a broader cosmology attached to the broomstick that was operating within these individual communities? Why jump a broom for matrimony? Why jump anything at all? Such questions require the researcher to sift through sources that can be both complementary and contradictory. Considering that broomstick traditions were often transmitted through oral testimony, the ceremony acquired different meanings to descendants who either embraced or rejected its utility. These sources can appear scattered and disarticulated if each group is analysed in isolation, but by examining the custom as a product of transatlantic exchange, we can produce a cultural genealogy that ties its many practitioners together.

Netherlandish Proverbs (1559) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Gemäldegalerie, Berlin/Wikipedia

The exact moment a couple first ‘jumped a broom’ and were declared married is impossible to know for certain. But the historian Lizzie Marx has uncovered an early visual account connecting matrimony with broomsticks. In 1559, the Flemish artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder made Netherlandish Proverbs, an odd and amusing painting. He represented Dutch proverbs and phrases literally so that, for example, the idiom ‘to bang one’s head against a brick wall’ – that is, trying to achieve the impossible – is rendered as a man actually smashing his head against a wall. There are about 126 such mini-scenes crowded into the frame and, if one looks closely, toward the painting’s upper-left corner, there’s a couple kissing beneath a broomstick protruding from the window of a house. The privacy of this kiss suggests it was undertaken clandestinely by a young couple intent on hiding their affections. Marx argues that this represents a phrase called ‘marrying under the broomstick’. Though this symbolic act of marrying under the broomstick is visually different from the act of jumping over a broomstick, Bruegel’s portrayal suggests that, by his time, there was an established association between the broom (a phallic object, note) and extralegal forms of marriage that preceded the more thoroughly documented jumps taken in the British Isles.

Choosing the broomstick as the matrimonial object also likely extended to omens and symbols of witchcraft popular in early modern Europe. The British Romani believed that the broomstick was ‘emblematic of evil, the insignia of a witch’, according to the folklorist Louise Jordan Miln, and a couple’s successful leap over the object suggested that their love could overpower malevolent forces. Testimonies from the enslaved in the US occasionally mention similar ideas, asserting that a successful leap over the broomstick ensured that evil wouldn’t trouble their domestic space. Oral traditions throughout Appalachia reveal that the broomstick was often placed at the doorstep of the newlyweds’ new residence to prevent witches from entering their home. The only group that doesn’t broadly associate the custom with metaphysical necessities is the Louisiana Cajuns, who seemed to use it for practical purposes if a minister was unavailable, or as a symbol of resistance against an overbearing Catholic Church.

The proverbial leap over the broomstick held various meanings among English-speaking communities in Britain and the US. Many used the expression ‘jump the broom’ as a colloquialism for ‘get married’, specifically when they wed outside ecclesiastical or state authority. To ‘jump the broom’ simply meant that a couple married in a quick ceremony undertaken to save the bride’s reputation in the case of a pregnancy occurring before the marriage. The colloquialism was used so often that scholars such as Rebecca Probert has questioned if ‘jumping the broom’ was meant literally, or simply as an expression that described ‘ersatz’ couplings. In a series of interviews conducted in 1926, one folklorist even doubted the authenticity of claims that jumping over the broomstick actually occurred among the ‘English Gypsies’, encouraging researchers to ‘proceed warily’ when examining such descriptions.

Enslaved people found meaning in rituals that slaveowners mocked or dismissed

The mixture of claims between researchers who argue for a literal leap and those who assert it was nothing more than a figurative expression is confusing if each group is examined in isolation. The best evidence for a literal leap over the matrimonial broomstick stems from an interconnected Atlantic paradigm, in which the cultural expressions of enslaved people and rural white people in the US are placed alongside those of communities in Britain. For those who doubt whether Romani or Welsh people physically jumped a broomstick, they must then explain why marginalised groups in North America used a similar custom. The fact is that the US version came from somewhere – and it seems most likely that it wasn’t Africa. The cultural precedents from migratory British communities are the original source.

Tracing a clear trajectory through which the broomstick wedding was brought to the US is difficult since its practitioners rarely left written accounts of their marital journeys. But one novel entitled Mr Penrose: The Journal of Penrose, Seaman, written in the late-18th century by the Welsh author William Williams, provides a reference point. Focusing on the experiences of a seaman named Llewellin Penrose, Williams imagines how British sailors passed on their cultural practices to non-white communities during the colonisation of the Americas. Penrose was a semi-autobiographical character based upon Williams’s own experiences travelling throughout the British colonies. In one episode, after shipwrecking in Central America, Penrose introduces the broomstick ceremony to his adopted multiracial community, explaining that it was used as a marriage ritual in his homeland. The novel then describes the community leaping over the matrimonial broomstick and confirming its legitimacy. Though fictional, this early reference reveals one way in which broomstick weddings arrived across the Atlantic and contextualises how they spread from the practices of British migrants.

Then, at some unknown point, enslaved people of African descent acquired the broomstick custom, and the tradition became embedded in their communities across generations. Though they shared a common thread in the physical leap over the object, no two plantations were quite the same. Documents reveal that some couples leapt over the broomstick multiple times, while others jumped backwards, or sometimes only one partner jumped. Sometimes couples faced one another during the leap, while others looked forward. Enslaved people in the US hold the largest and most diverse collection of accounts describing the broomstick wedding. The record shows how they innovated the ritual after its acquisition, revealing a cultural evolution that was unique to their circumstances in chattel slavery. Forbidden from obtaining legally recognised marriages, enslaved people found meaning in rituals that slaveowners mocked or dismissed. Reorienting the ceremonial performance was one way to assert agency under oppression.

We are still learning how the broomstick wedding impacted enslaved peoples’ cultures and how it informed their views on marriage. Like other folkloric sources, many who spoke about the ritual reflected on their own unique experiences, or commented upon those of their ancestors. It’s not uncommon, for instance, for a respondent to tell their interviewer that their parents or grandparents ‘jumped the broom’, but that they never did it themselves. Naturally, some historians such as John Blassingame have doubted that enslaved people took the custom seriously, if they performed it at all. Consequently, the broomstick wedding was relegated to the margins of scholarly research and few historians attempted to explain its cultural origins or relevancy for African Americans.

But, as noted, enslaved people weren’t the only group in the US to jump the broom. White communities in Appalachia also leapt over matrimonial broomsticks for both supernatural and practical purposes. Cajun communities in the Louisiana bayous used the broomstick wedding to challenge ecclesiastical authority, and people living in small towns throughout the American West sanctioned their marriages communally by jumping over a broomstick when a minister was unavailable. Like their counterparts across the Atlantic, these communities faced geographical isolation and social ostracism. The broomstick wedding provided communal endorsement for their marital unions that was independent of state or religious interference.

The custom’s multicultural attachments, however, remain a source of confusion – if not outright contention – for many. Since the custom was repopularised among African Americans in the late-20th century, white folklorists and popular authors have debated its origins. Because of its near-exclusive attachments to Black Americans following the release of Roots (1977), some columnists and wedding planners assumed the custom’s origins lay in Africa, with Ghana as the most referenced area. They argued that enslaved people reoriented their ancestral marriage practices under the conditions of slavery and created the broomstick wedding to symbolise their commitment in the face of oppression. Noticing that this idea was gaining popularity, professional folklorists responded by citing similar rituals existing among Romani communities in the British Isles, alongside similar traditions found in the oral histories of Welsh communities. They argued that the African-origins thesis held no empirical weight, while the European-roots thesis was backed up by transatlantic documentation. Though there are clear precedents in Europe, especially in the association between broomsticks and fertility, debate still rages in online forums and social media venues surrounding cultural appropriation and the ability of white people (specifically in the US) to respectfully engage in the ritual.

But the very obsession with origins – which is at the heart of this issue of cultural ownership – is, I’d contend, the wrong focus. It’s most important for scholars to examine how these aforementioned communities all engaged with the custom historically, and how they have viewed its importance for their identity across generations. Determining the origins of a folk custom that was used by those who left few self-authored documents is nearly impossible. In other words, if one finds the custom’s ‘first’ documented reference in northern Wales, that doesn’t mean that communities in that region were the first to use it. Cultural practices are malleable and adaptable among the groups they influence, and if those groups left few written histories, it’s less important to argue who ‘owns’ the custom, and more beneficial to comparatively examine the wide array of folklore to assess its diverse meanings across cultures. Only then can we determine how history informs the present and how we can learn from one another’s experiences.

The leap reflected a transcendent moment for those who were disenfranchised from the broader society

The broomstick wedding’s cross-cultural popularity is a direct product of its folkloric history, since it spoke to so many groups who shared a common experience of marginalisation in their respective societies. As the anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston explained:

Folklore is the boiled-down juice of human living. It does not belong to any special time, place nor people … it could be said that folklore is the first thing that man makes out of the natural laws that he finds around him.

If folk customs, as ritualised manifestations of folkloric beliefs, develop within this framework, it seems fruitless to argue origins or ownership. Neither folklore nor its customs necessarily require a cultural genesis, though tracking a tradition’s genealogy within a single group does have its benefits. Each community holds a practice that extends across generations. Even if it was introduced by outside influences, this reality is of little concern to them as the custom becomes a symbol of their identity, ancestry and cultural vitality.

Hurston further likened the broad category of folklore to a serving platter surrounded by many plates, but ‘each plate has a flavour of its own because the people take the universal stuff and season it to suit themselves on the plate … this local flavour is what is known as originality.’ Viewing the broomstick wedding as a broad category of folk practice, Hurston’s idea works in explaining the similarities and divergences of the ritual across the cultural groups that used it, even if we have little documented evidence of their cultural interactions. By comparing the many expressions of the broomstick wedding as it existed across various groups, we can understand the dynamic process of cultural exchange, even when the records don’t convey tangible interactions between those who express similar traditions.

In excavating the sources that reference jumping the broom, it becomes clear that many of the oral traditions are concerned with unpacking its cultural meanings, social contexts and symbolic qualities, both for the custom’s practitioners as well as its opponents. They rarely commented upon its multigenerational origins, but their descriptive material helps us understand its unique cultural significance for its users. Interviewed nearly eight decades after the abolition of slavery, some formerly enslaved African Americans claimed that their broomstick weddings were not only equal to their post-emancipation marriages – in which they were required to seek government recognition and formally register their marital bond – but were actually superior to them. They argued that enslaved people, whose domestic attachments could be destroyed at any moment by the predations of slaveholders, adhered to their commitments in a greater capacity than the generations who only knew freedom. As one formerly enslaved respondent put it in the late 1930s, the young people he knew were now only concerned with ‘vocin’ [divorcing]’. As the historian Tera Hunter argues, enslaved people married under unpredictable circumstances, in which their families were separated at the enslaver’s whim. Indeed, this legacy surely informed their criticisms surrounding the younger generation’s supposedly flippant approach to matrimony.

Across the Atlantic, members of the British Romani made similar assertions as they reflected upon their own broomstick marriages and the lasting devotion that was shared between spouses. No need for a church wedding, they asserted, since ‘a marriage with the broom is perfectly valid’. As an ostracised and marginalised community in the British Isles, the marital rituals used by an older generation represented their liminal status in British society. Though quick and simple, the leap over the broomstick reflected a transcendent moment for those who were disenfranchised from the broader society, regardless of the side of the Atlantic upon which they dwelled. It allowed practitioners to reimagine their own approach to performing the ritual and its unique meaning to their union. It was, to revisit Hurston’s words, the ‘boiled-down juice’ on the many ‘plates’ of populations who used this form of communal matrimony – no matter where it came from or who jumped the broom first.