An octogenarian Christian bishop is condemned to death for his beliefs. Even while bound to a wooden stake, as Roman authorities order his immolation, the monk still refuses to blaspheme against his god. A crowd gathers to watch, including the monk’s companions, who look on with horror and reverence as the pyre is lit. But the flames fail to extinguish his life, and a dagger finishes the job. The bishop Polycarp is dead.

His companions rush to gather the body, creating a commotion so chaotic that Roman authorities must physically restrain them. They seek his remains, hoping to preserve Polycarp’s bones as relics of suffering and dedication. Through death, the monk becomes a martyr, and Saint Polycarp’s story begins to spread Christianity further across the Roman Empire. But his martyrdom represents more than the spread of a single oppressed religion: Polycarp’s sacrifice in the 2nd century CE shows what it can mean to wield death as a form of resistance. A form that will shape the ambit of political action in the millennia that follow.

The history of Christianity is filled with martyrs like Polycarp, but martyrdom is not an invention of Christianity. In the settled societies of the Mediterranean basin, martyrs challenged repressive political power. Members of various philosophical streams, prominently Stoicism, used self-inflicted and assisted death as a performance of their exalted position over a debased society. A well-known example is Socrates who accepted the death penalty for corrupting the youth of Athens during the 4th century BCE. Defying death, he reasoned, would have set a negative example to those supposedly ‘corrupted’ youth. Over the following centuries, as civilisations rose and fell, philosophers and holy men of all kinds used death to symbolically oppose unjust rule – in some circumstances, death became the sole avenue for action. But was it effective?

What may often seem a desperate and futile act can sometimes assume critical political expedience. For this reason, death’s uses have only proliferated since the days of Polycarp. Understanding the political afterlife of death, specifically through martyrdom, has become only more complex and urgent in a world of oppressive state control, colonisation, insurgency and counterinsurgency. While death inevitably brings certain processes to a swift halt, what novel possibilities can it open?

An understanding of death’s political possibilities could be informed by turning to relatively recent examples of philosophers, activists, Marxists, insurgents, paramilitary groups and Buddhist monks who have used death to achieve their goals. But there is a longer trajectory to the political uses of death, one that requires tracing the history of sacrifice in the Abrahamic traditions. Judaism, Christianity and Islam have all employed death to further their cause and rally members for political ends. The sacrality of martyrdom and martyrs in these religions cannot be overemphasised. Although these religions focus heavily on the moral direction of quotidian conduct to avoid otherworldly damnation, martyrdom is seen as an extraordinary avenue to achieve communal esteem and ethereal salvation.

One of the inflection points for this longer trajectory begins with Abraham. In the Book of Genesis, God commands Abraham to sacrifice his son, Isaac, as a ‘burnt-offering’:

Take now thy son, thine only son, whom thou lovest, even Isaac, and get thee into the land of Moriah; and offer him there for a burnt-offering upon one of the mountains which I will tell thee of.

Abraham builds the altar, lays down the wood, binds Isaac, and prepares to sacrifice his son, but God stops him – a nearby ram becomes the ‘burnt-offering’. The binding of Isaac and his potential sacrifice demonstrate the centrality of sacred death in all the Abrahamic faiths.

During the Greek and Roman empires, as Jews faced increased persecution, sacrifice became central to Jewish life and theology. The role of martyrdom was further cemented through various eras of persecution under the rule of Christians and Byzantines. Even today, the Jewish victims of the First Crusade (1096 CE) are almost unanimously revered as martyrs. However, martyrdom is not always easily incorporated. Its role has been complicated by the Holocaust: does the widespread death of Jews in the mid-20th century constitute martyrdom? According to Rabbi Shira Lander, applying the concept of martyrdom, in terms of divine judgement, to the Shoah is often considered blasphemous. However, numerous instances of collective and individual resistance during the Second World War, within concentration camps or the Jewish Ghettos, are undoubtedly viewed through the lens of martyrdom.

Christians understand Christ’s death as a redemptive act in the service of humanity

In contemporary times, the Jewish tradition of martyrdom is seen in the Zionist movement and the conduct of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), who have efficiently employed it in the name of territorial annexation and national sovereignty. Within their ranks, the prestige associated with sacrifice results in substituting material rewards for symbolic gain. Martyrdom dominates the imaginary of the IDF. David Ben-Gurion, the founder of the state of Israel, considered the knowledge of martyred biblical military heroes a necessary precondition for proper induction into the Israeli military. The forces operate within what the Israeli political scientist Yagil Levy calls a theocratic framework of sacrifice. But it’s important to note that Zionism and the IDF do not singlehandedly encompass either the Jewish theological doctrines or the evolution of Jewish militancy and its culture of martyrdom.

Christianity also coalesces around sacred death: the binding of Isaac foreshadows the crucifixion of Jesus. Christians understand Christ’s death as a redemptive act in the service of humanity, an ultimate sacrifice to selflessly atone for humanity’s sins. While many scholarly traditions view crucifixion as a passive act, representing victimhood, the simple fact that it continues to deeply resonate within Christianity makes it anything but passive. In the Apostolic Age, from around 33 to 100 CE – the first decades of the religion – the veneration of sacred death was further cemented. It became so central to early Christian culture, that many scholars define Christianity as the emergence of a ‘cult’ of martyrdom. Saint Polycarp’s death contributed to this view.

One of the most influential contributors towards this glorification of martyrdom was Eusebius of Caesarea, a Greek bishop, polemicist and historian who produced multiple works about Christian martyrology during the 4th century CE. His text On the Martyrs of Palestine details the stories of Christians who were tortured and killed. Its first sentence begins:

Those Holy Martyrs of God, who loved our Saviour and Lord Jesus Christ, and God supreme and sovereign of all, more than themselves and their own lives, who were dragged forward to the conflict for the sake of religion, and rendered glorious by the martyrdom of confession, who preferred a horrible death to a temporary life, and were crowned with all the victories of virtue, and offered to the Most High and supreme God the glory of their wonderful victory, because they had their conversation in heaven, and walked with him who gave victory to their testimony, also offered up glory, and honour, and majesty to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Ghost.

Early Christians who were martyred, including those described by Eusebius, became the focus of pilgrimage, as believers journeyed to see the remains or burial sites of those who had been ‘rendered glorious’ by ‘a horrible death’. From the time of the crusades to the Middle Ages, the ‘cult’ of martyrdom intensified. By the time the Christian theologian Thomas Aquinas wrote Summa Theologiae in the late 1300s, he described martyrdom as a ‘perfect’ human act – in fact, singularly perfect, as a symbol of virtue and fortitude. But for Aquinas, the ‘perfect notion of martyrdom requires that a man suffer death for Christ’s sake.’

In Islam, death became part of a central strategy. As in Judaism and Christianity, death was used to establish and proliferate the religion. In fact, sacred death played such a key role in the early years of Islam, between 622 and 950 CE, that martyrdom became a military problem. These early years were an era of contentious politics and fierce battles, in which sacrifice for God represented an ultimate authenticity of belief. There is evidence that military commanders were irritated by the abundance of self-sacrificing martyrs and the lack of prudent fighters who displayed a reluctance to die. One prominent example, according to the historian Alfred Morabia, were the muttawi’a or volunteers who readily sacrificed themselves during Muslim confrontations against the Byzantines, especially during the 7th and 8th centuries.

In the Quran, Islam’s foundational text, martyrdom is inextricably tied to the struggle for faith, and it remains deeply venerated. Martyrs are accorded an exalted status as well as a guarantee for a secure afterlife. Multiple verses attest to this, the most repeated being from the chapters Al-Baqarah and Al-Imran:

وَلاَ تَحْسَبَنَّ الَّذِينَ قُتِلُواْ فِي سَبِيلِ اللّهِ أَمْوَاتًا بَلْ أَحْيَاء عِندَ رَبِّهِمْ يُرْزَقُونَ

‘But do not think of those that have been slain in God’s cause dead. Nay, they are alive! With their Sustainer have they their sustenance …’

وَلاَ تَقُولُواْ لِمَنْ يُقْتَلُ فِي سَبيلِ اللّهِ أَمْوَاتٌ بَلْ أَحْيَاء وَلَكِن لاَّ تَشْعُرُونَ

‘And say not of those who are slain in God’s cause, “They are dead”: nay, they are alive, but you perceive it not.’

Within the logic of Islam, martyrdom is legitimised when it advances the aims of the faith. However, according to Mahmoud M Ayoub, an influential Lebanese scholar of Islam, in some branches of Islam a martyr with secondary motives – including the desire to claim material reward, display bravery or defend their wealth, family or land – is no less legitimate, as long as faith is the primary motive.

Muslims slain in prolonged battles against the occupying US military were virtually accorded the status of saints

When a Muslim dies, their body is washed and wrapped in a shroud before burial. But Muslim martyrs are displayed in an open casket wearing the clothes they died in. According to the Islamic tradition, they have already been purified by their death – by a selfless act in service of the faith. Special rituals and occasions are also associated with the remembrance of the martyrs’ sacrifice, especially for those slain during the formative years of Islam. When a Muslim becomes a martyr, their family members and acquaintances are discouraged from mourning. Instead, they must express gratitude. According to the Quran, martyrs are not dead. In a temporal sense, the continued ritual performances of remembrance keep them alive in the afterlife.

These performances may take place at the burial sites of martyrs, which are often positioned away from regular graveyards. The graves of martyrs hold reverential status within Muslim societies.

In 2002, the veteran war correspondent Robert Fisk visited a martyrs’ graveyard in Kandahar, Afghanistan. He describes the way that those buried there – Muslims slain during prolonged battles against the occupying US military – were virtually accorded the status of saints by locals:

The people of the Taliban’s former caliphate tended the graves in their hundreds. On Fridays, they came in their thousands, travelling hundreds of miles. They brought their sick and dying. Word had it that a visit to the graveyard of bin Laden’s dead would cure disease and pestilence. As if kneeling at the graves of saints, old women gently washed the baked mud sepulchres, kissing the dust upon them, looking up in prayer to the spindly flags that snapped in the dust storms.

I grew up in India-administered Kashmir, a region marred by decades of conflict, popular insurgency and ferocious counterinsurgency. Here, the idea of politicoreligious sacred death remains a pervasive and omnipresent feature of daily life. Those believed to have been slain for the cause of Kashmir’s freedom, and Islam, are popularly revered within the social milieu as their families receive increased social acceptance and status. Before burial, the bodies are displayed openly in large funerary processions. After attempting to touch the feet, face, beard or torso of these bodies, the mourners caress their chests or faces, as if to gather piousness. The bodies are then buried in special graveyards that are spread across Kashmir’s towns and villages. During these funerals, family members apply henna on the hands and feet of their slain kin, in addition to showering them with sweets. This is done in imitation of the rituals that are generally carried out during elaborate marriage ceremonies in Kashmir. The performance that follows death is a mix of celebration and mourning. They celebrate because the dead have received the highest level of spiritual salvation that can be accorded to a Muslim: Jannah (paradise).

The history of martyrdom in the Abrahamic traditions shows the strategic role that sacred death played in the formation of these faiths – a ‘strategy’ that furthered spiritual and political aims. Through these traditions, death became discursively understood not only as a ‘perfect’ act in the present, or a way of living forever, but also a means of resisting oppression and creating change. But, in Kashmir, sacred death takes on an explicitly political register. Often, the only dissentious politics that can be performed in Kashmir revolves around death.

In pictures and videos, the insurgent is seen touting a gun, pointing the index finger of his right hand to the sky

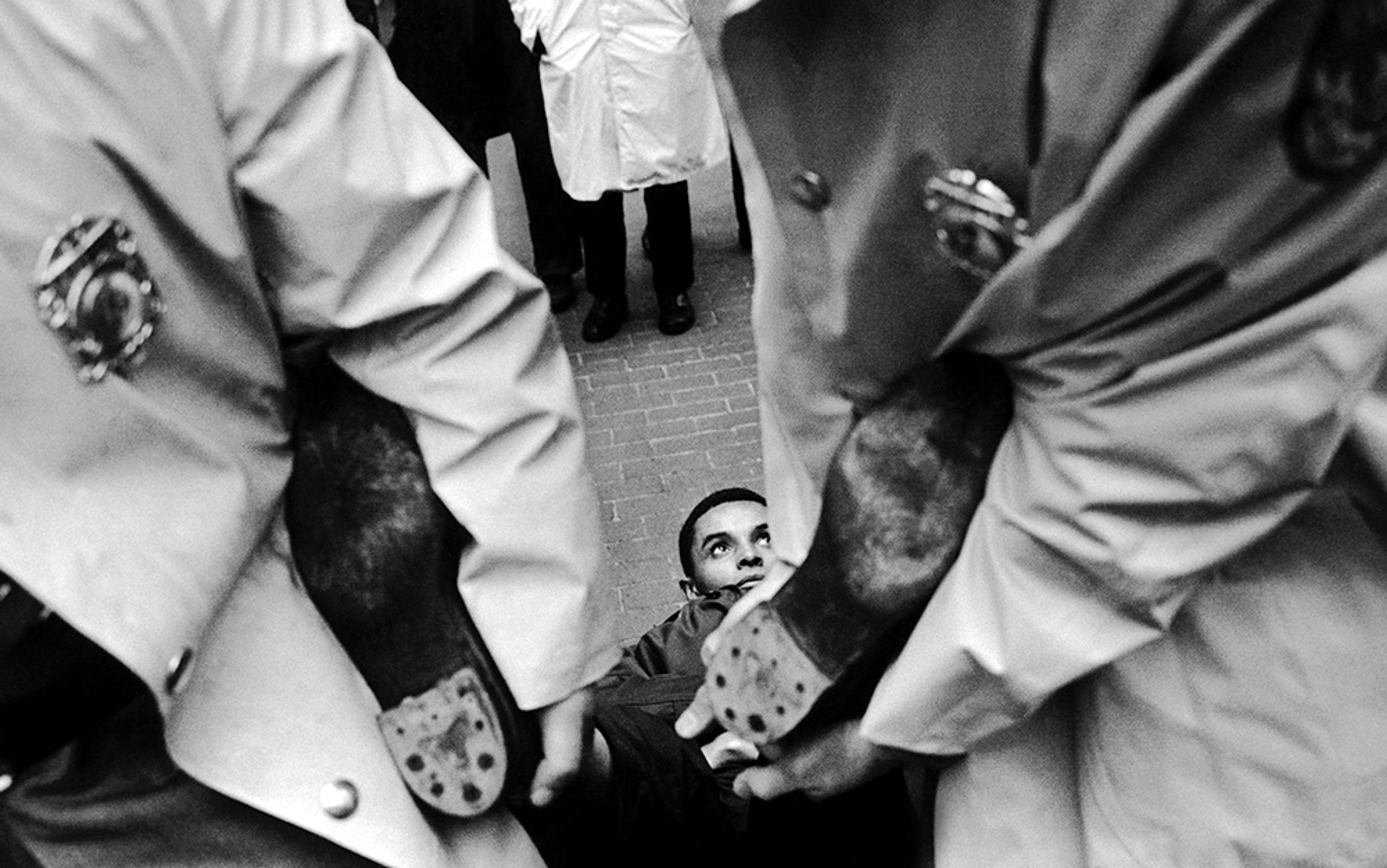

On university or college campuses, where unionising and campaigning remains virtually banned, students often organise funeral prayers for those who they believe are martyrs. However, state authorities have now put an end to these funerary processions by refusing to return the bodies of slain Kashmiris to their families. Instead, they are buried discreetly in faraway border areas. Halting this performative culture of martyrdom was seen as a strategic victory by one of the region’s top-ranking police officials because the observance of large-scale funerary processions significantly enabled recruitment within insurgent ranks. The seizure of bodies by state officials and the performative culture of martyrdom used by Kashmiris to express political resistance reveal the critical position of death within the region’s politics.

The notion of death remains an active core around which the insurgency coalesces. At the end of dogged gunfights between insurgents and the Indian military, dead rebel recruits are often found carrying extremely low-grade weaponry or no weapons at all. This points towards an alternative motivation, beyond material gains, that seems to drive the Kashmiri insurgency against the state’s military structures. This motivation becomes more stark in the visual material created by these young men in the immediate aftermath of joining the insurgency. In pictures and videos, the insurgent is seen touting a gun and pointing the index finger of his right hand to the sky, signifying the Shahada or ‘witnessing’ of the oneness of God. The Arabic term for martyrdom, ‘shaheed’, which appears in the Quran, literally refers to the act of witnessing. Etymologically, this is close to the English, Greek and Syriac words ‘martyr’, ‘martus’ and ‘sahda’, respectively, which all refer to the act of witnessing.

In recent times, the insurgents and their families have also recorded what are known as ‘last calls’ or ‘final calls’. In these phone conversations, an insurgent, who is engaged in a gunfight with the Indian military and has no hope of escaping alive, calls back home for a final farewell. These deeply personal and intense phone calls, which are recorded and then circulated on social media, give insight into the dynamics of the insurgency in Kashmir, illuminating the motivations that drive Muslims to fight despite facing overwhelming odds against India’s enormous counterinsurgency grid. In the calls, pleasantries are exchanged before the young insurgents emphasise their proximate martyrdom for the sake of Islam, and urge others to carry forward ‘the mission’, a euphemism for armed insurgency against the Indian state.

This practice of death as politics appears in other contemporary contexts, most prominently in Palestine. In December 2022, Palestinians mourned the killing of 23-year-old Ahmed Daraghmeh, a professional soccer player. He was killed by the Israeli military during a raid on the West Bank city of Nablus. His funeral was attended by hundreds if not thousands of people, and turned into a site of protest against the occupation. Whether it be after the killing of a Palestinian civilian or of a militant commander, funerary processions have always been potent settings for Palestinians to express political resistance to the Israeli occupation.

An important Arabic term in the context of Palestinian self-sacrifice and martyrdom is ‘Istishhad’. According to Bassam Yousef Ibrahim Banat, a Palestinian sociologist, the term denotes the act of self-sacrifice for the cause of Palestinian liberation. Banat writes:

Self-sacrificing for the sake of the group is a term expressed by Palestinians through the ‘Istishhady’ (suicide martyr) which has religious and popular significances given to the person, who with premeditation and full consciousness, makes a decisive decision to sacrifice himself.

In recent years, the Israeli authorities have actively focused on putting an end to this expression of Palestinian politics through death. The funerals of those who are conceived to be martyrs are often met with brutal military violence, and remain criminalised. This was demonstrated during the funeral of Shireen Abu Akleh, a Palestinian American journalist shot dead in May 2022 by Israeli forces while covering a military raid in the occupied West Bank. The Israeli military warned Abu Akleh’s brother against chanting slogans and displaying Palestinian flags at the funeral, and then attacked the mourners and pallbearers.

Shaban’s body was released after four months. Authorities ordered the family to complete the funeral in an hour

In an apparent attempt to halt this rallying around sacred death, Israeli authorities sometimes confiscate the dead bodies of Palestinians to use as leverage. These bodies are held for months in refrigerated mortuaries and released only after protracted negotiations with Palestinian families. The conditions of release often hinge upon how the subsequent funerals will be organised by these families. Israeli authorities will urge them to bury their dead in the middle of the night, with minimal visibility. For the social scientist Suhad Daher-Nashif, this ‘colonial management of death’ complicates the Palestinian experience of mourning and turns it into a ‘spiral’ rather than a ‘linear’ phenomenon. Through an interview in 2016 with the father of a killed Palestinian named ‘Basel’, Daher-Nashif shares the pain of being denied closure:

My son was held for 75 days; every day we heard something different; they played with our emotions. On the day my son [was] killed, two more also were killed. … Death became part of our daily life; we became 18 families; this distracted me from my own trauma and [I] felt that it was a trauma for the whole community. We began to create pressure to get the corpses back. After 45 days of waiting I couldn’t stand it anymore. I couldn’t work. One Thursday we received the news that they would release them the next day, Friday. They chose that day because a snowstorm was expected. They chose it especially to prevent us from having an appropriate funeral.

The experience of Basel’s father is not exceptional. Samah Jabr, a Palestinian psychotherapist, writes about the exhausting negotiations between Israeli authorities and the family of Ahmad Abu Sha’aban, a young Palestinian killed in August 2015. Shaban’s body was released after four months, and authorities ordered the family to complete the funeral rituals in an hour or so. This protracted crackdown against mourning in Palestine again reveals how critical death has become for political expression in the region.

How should we grapple with what is at stake in this fraught dynamic of death, power and politics? For Achille Mbembe, the Cameroonian public intellectual and critical theorist, manifestations of power and sovereignty are forms of ‘necropolitics’. From this perspective, contemporary power is the condition of wielding death: being able to apply it, withhold it, prolong it. This power, Mbembe demonstrates, has led to the creation of ‘death-worlds’ inhabited by ‘living dead’. But death and politics are tangled in complex ways. To conceptualise the subversion of necropolitics, Mbembe uses the figure of a Palestinian suicide bomber. The long history of martyrdom in the Abrahamic traditions, or Kashmir, provide other examples.

But the question remains: what utilitarian political end, if any, does death serve, especially in the contexts of unpopular rule, armed insurgency, and sovereign necropolitical death? G W F Hegel has one response. Hegel describes voluntary encounters with death as non-nihilistic, and maintains that these acts form an essential element of subject-formation. Confronting death, whether as an individual or collective, inevitably transforms the subjective experience of the living or those left behind. Terry Eagleton, the Marxist literary critic and public intellectual, has another response. In his treatise on martyrdom, Radical Sacrifice (2020), Eagleton writes about the ways that voluntary death can overcome the ‘demonic compulsion’ of the Freudian death drive and transform what appears to be a necessity into a practice of freedom. When everyday life is pervasively animated by oppressive forms of enforced death, can death itself be appropriated and turned into an act of resistance and freedom?

Death is a preferable form of political expression for people oppressed by conditions that stretch across time

Eagleton is not the only one thinking of death as freedom. In Starve and Immolate (2014), the political theorist Banu Bargu continues this thread by offering an alternative to sovereign necropolitics: necroresistance. What is striking in Bargu’s case is the way that this form of resistance overlaps with Abrahamic martyrdom. Through the example of imprisoned Marxist dissidents held in the depths of Turkey’s carceral system, Bargu powerfully shows how death, and its attendant rituals and discourses, can assume a theological character even among the supposedly nonreligious. This is not incidental. Bargu describes theologisation as a necessary precondition for necroresistance, and maintains that it has resulted in the production of a new kind of Marxism for the Communist cadre in Turkey: ‘sacrificial Marxism’, which involves martyrdom being systemically appropriated as a ‘central ethico-political value’ and transformed into a vehicle for ‘ideological and cultural propagation’. Necroresistance, when viewed in opposition to necropolitics, can become a potent force of popular political expression.

When is such expression appropriate? For Frantz Fanon, the great philosopher and anticolonial militant, death is a preferable form of political expression when people are oppressed by conditions that appear to stretch across time – an all-encompassing ‘web of three-dimensional violence’. Ending what appears to be a territorially endless and temporally eternal regime, by any means necessary, may include death.

This form of death cannot be dismissed as simply desperate and futile. Not for Fanon, for Bargu, for Kandahar’s insurgents, for Polycarp, nor those whose martyrdom became an expression of dissentious politics. For them, and others, death may not only be logical, but revelatory.