The YouTube video is grainy and little more than 90 seconds long. A group of men sit under olive trees on a hill, in a scene that would resemble a cheery picnic were it not for the rifles resting at their feet. Digital pixelation dances across their faces in an effort to keep their identities hidden, though one fair-skinned young man with a reddish beard is clearly visible. He looks directly at the camera, a big smile spreading across his face. His sunny demeanour and chunky frame invoke the strip malls and Dunkin’ Donuts of his native Florida. But when a building in Syria’s Idlib province exploded in a cloud of dust on 25 May 2014, it turned out that this young man might have been responsible. He died, as was his wish, a martyr in a holy war.

The Reuters voiceover tells the story from scratch: this joyful American took the Arabic name Moner Mohammad Abu-Salha and set out to die for his beliefs. But why would someone from a middle-class background in the United States, who could have led a tranquil life, sacrifice himself for a cause?

In a breakthrough paper published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology late last year, the psychologist Jocelyn Bélanger and team at the Université du Québec à Montréal identified the personality traits of those with a ‘psychological readiness to suffer and sacrifice’ his or her life for a cause. The result, a Self-Sacrifice scale, could be a boon to anti-terror operatives across the globe, especially in the wake of attacks on sites ranging from Paris and Copenhagen to Peshawar and Nairobi – places where terrorists have this century claimed thousands of lives.

The new scale, based on eight integrative studies, emphasises the significance of idealism and love of a cause, by contrast with previous martyrdom profiles. One of the samples studied were incarcerated terrorists – other population samples were tested on the relationship between personality traits, commitment to a cause and preparedness to sacrifice for that cause. Former martyrdom profiling, based chiefly on demographics, focused on young men with poor education alienated from mainstream society. Some painted would-be suicide terrorists as mentally unstable, as was the case with Man Haron Monis, who launched the attack in a Lindt chocolate café in Sydney last year. But Bélanger and his team say that outward markers such as race, age, level of employment, even emotional health, mean little compared with the individual proclivity to ‘attribute greater importance to their cause than [to] their own lives, even the lives of others’.

Eliciting martyrdom in psychological tests presented a dilemma. ‘Obviously,’ said Keren Sharvit, a psychologist at the University of Haifa and one of the researchers on the studies, ‘due to ethical concerns, we were not able, nor did we want, to induce people to actually sacrifice their lives under laboratory conditions.’ In one part of this set of studies, a simulation asked 119 college student participants of varied background to name the causes they believed in, from animal rights to cancer research. Then, to test the strength of the volunteers’ commitment, the researches offered to pay $1 to that charitable cause for each teaspoon of Tabasco sauce that the participant drank.

How painful can drinking Tabasco sauce be? So painful that even the LA Beast, a professional competitive eater and YouTube entertainer who prides himself on performing acts of ‘digestional derring-do’, struggles to drink the stuff. When Bélanger’s team member Julie Caouette, a psychologist at Carleton University in Canada, indulged, she reported that ‘eating Tabasco sauce by the spoonful is quite painful! And to keep eating a spoonful one after another for the sake of a cause requires a certain sense of self-abnegation and a willingness to forego personal well-being.’

Even if blowing oneself up were instantaneous and the individual didn’t feel physical pain, adds Caouette, there is still great psychological duress. ‘This is not mentioned in our paper, but suicide bombers usually go through a long preparation to make them ready to become suicide bombers.’ They have to say goodbye to or cut off contact with their families, who might not approve of their actions. ‘In the end,’ she said, ‘martyrdom can take many forms of self-sacrifice, whether feeling pain or losing one’s life.’

The Self-Sacrifice scale creates an unprecendented psychological test of the degree to which individuals are willing to give up ‘their wealth, their important personal relationships, and then their life’ for something they value more highly. As the researchers point out, such traits can have intensely pro-social outcomes as well as destructive ones. Contrary to the idea that martyrs don’t value their life and are depressed, the study found that these individuals were usually constructive and motivated. Still, they were simply willing to sacrifice their closest relationships for something that mattered more – their cause.

Bélanger’s theory is corroborated by the fieldwork of anthropologist Scott Atran of the University of Michigan, who interviewed would-be and convicted terrorists about their extreme commitment to their organisations and ideals. In November 2014, Atran published The Devoted Actor, Sacred Values, and Willingness to Fight for the US Department of Defense, profiling those likely to join the Islamic State, with a focus on two neighbourhoods in Casablanca in Morocco associated with militant jihad. One neighbourhood had produced five of the seven Madrid train bombers in 2004 and another produced tens of volunteers who perished in suicide bombings in Iraq and now Syria. So far, more than 2,000 Moroccans have joined jihadi groups.

For their research, Atran and his team went into those neighbourhoods and met with the families and friends of the militants. They got to know them, how they lived, and gained insight into their beliefs. Atran found that young men tend to join in a group of three to four friends who recreate a family unit through their camaraderie. They are brothers in arms, devoted to one another.

Instead of giving up family and close relationships, as Carleton’s Caouette suggested a martyr must do, Atran sees a family-like unit emerge. With martyrs willing ‘to fight unto death with and for genetic strangers’, Atran’s report suggests, there must be some inspiration, and family-like relationships could be it.

Members of human communities routinely sacrifice their own lives so that the community can go on

But believing in the cause itself was a profoundly important factor, too. Atran found that the volunteers had to believe in the sacred value of the Islamic state, including both sharia law and the caliphate, a government led by a literal successor to the prophet Muhammad. In an email, Atran explained:

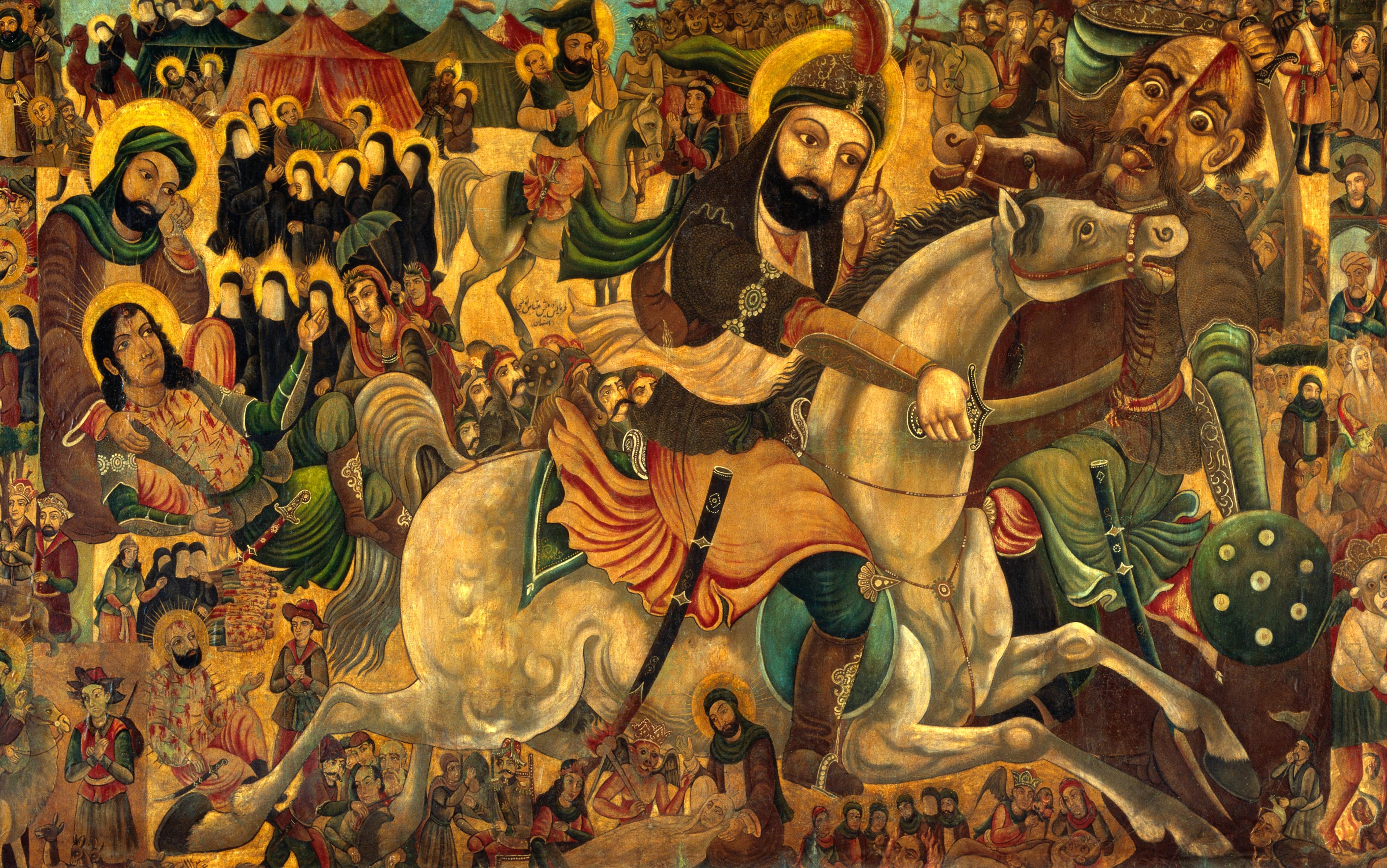

Just about every Muslim kid knows a gazillion stories about the first three Caliphs and Companions of the Prophet – the fatherly Abu Bakr, the kindly (except to Islam’s enemies) giant Omar, the benevolent billionaire Othman – who in less than 30 years brought together a bunch of fractious desert tribes under a codified consensus of what Mohammad was aiming for, to forge the then-largest empire in the history of the world … people are yearning for something in their history, in their traditions, with their heroes and their morals … That is key to understanding what is going on.

In March 2014, when the self-proclaimed emir of ISIL [the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant] Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi first floated the idea of the caliphate through thousands of Twitter hashtags and then on 30 June, he declared the caliphate, he did so to specifically address the major criticisms, concerns, gaps, fears and yearnings of the relevant audience, and he outlined a strategy against his opposition.

The symbols found in these messages could inspire martyrs for years to come. It might sound trite to say that symbolic understanding is enough to corral a formidable army, but some evolutionary thinkers believe that such symbolic reasoning is the key to the success of Homo sapiens as a species. The fossil expert Ian Tattersall of the American Museum of Natural History, for example, has argued that the ability to think symbolically is what made our ancestors different from their cousins, the Neanderthals. This could include the ability to make future plans or conjure the idea of a divine being, but it can also refer to sharing a common cause.

Atran reminds us that just as the conflict with Afghanistan in the 1980s sowed the seeds for the terrorist attacks on the West in the early 2000s, so too the conflict with the self-declared Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (or ISIS) today will engender future attacks by providing sacred values and a fighting spirit around which brothers-in-arms can rally.

Democratic institutions rarely allow for this kind of absolute belief in a sacred value, and scientists have worked to uncover the inherent self-interest of apparently altruistic behaviour. Richard Dawkins’s concept of ‘the selfish gene’ holds that organisms are motivated to pass down their genetic material. By extension, the theory goes, each person acts altruistically only to advance the cause of his or her genetic kin. Dawkins’s idea, that individuals help the group – even martyr themselves – only out of genetic self-interest, continues to commandeer mainstream thought.

The notion of the selfish gene has been challenged by the evolutionary biologists David Sloan Wilson of Binghamton University in New York and E O Wilson of Harvard University in Massachusetts, who hold that group affiliation itself can drive behaviour, sometimes more than genetic advantage. They point to the elegant, gelatinous Portuguese man o’war, a malleable marine animal known to physically attach itself to others of its species when threatened by predators. Individuals of the species take up roles of locomotion, feeding and digestion, and subsume themselves for the greater good of the bigger organism. Wilson and Wilson contend that the strategy is observable in human society when individuals come together to form a group that competes for resources with other groups. Members of human communities routinely sacrifice their own lives so that the community can go on – even when the individuals they save have no biological relationship to them at all.

We might view the caliphate as bizarre and opaque. Yet it is precisely that sacred value that allows a hodgepodge of mixed nationalities with no genetic ties (and therefore little individual evolutionary incentive) to defeat domestic police and armed forces with far more power and reach. To wit: the armies of Syria and Iraq have fraternal relationships inside their units but lack overarching sacred values that provide a stronger internal glue.

‘We underestimated the Viet Cong … In this case, we underestimated ISIL and overestimated the fighting capability of the Iraqi army,’ James Clapper, the US Director of National Intelligence told the Washington Post. ‘It boils down to the power of devotion and predicting the will to fight.’