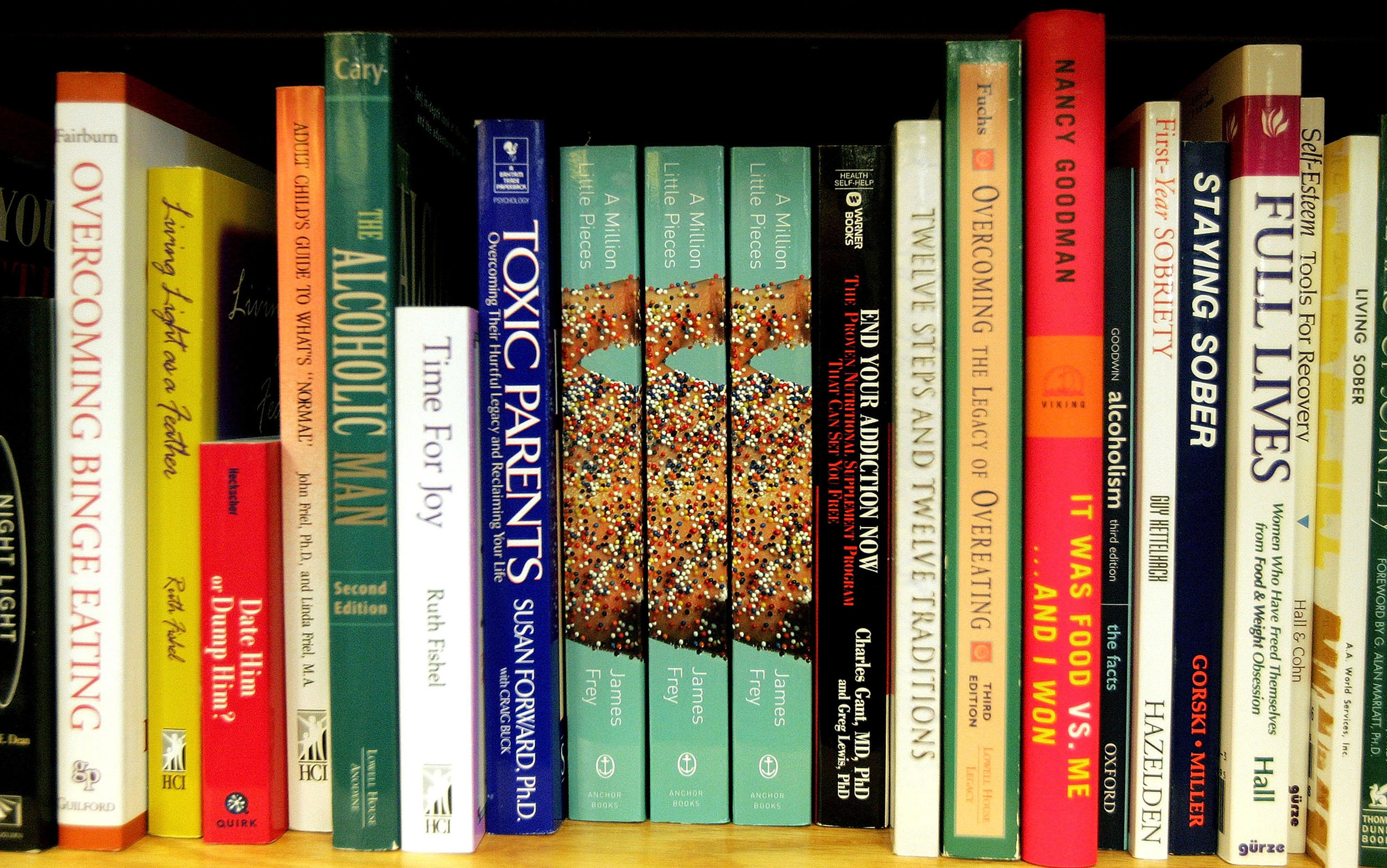

Most people enter the self-help realm while planning a personal improvement project, a kind of steam-cleaning of the soul. I fell into it by mistake. Maybe the allusion to a familiar poem was what made me pull M Scott Peck’s The Road Less Travelled (1978) off my parents’ shelf as a young teen. In any case, I was hooked. Beset by typical middle‑school problems – bullies, fickle friends, chronic wallflower-dom – I was intrigued by the claim of this psychiatrist from Connecticut that suffering could have a noble and necessary purpose, as long as you showed the fortitude to tackle your issues head-on. ‘When we avoid the legitimate suffering that results from dealing with problems,’ Peck wrote, ‘we also avoid the growth that problems demand from us.’

A budding skeptic confronted with an array of belief systems, I felt that Peck’s emphasis on dedication to truth helped to ground me. And when I was tempted to nurse crushes as an alcoholic might a sloe gin fizz, Peck was there to remind me that true love involved a conscious choice to nurture the other partner’s wellbeing. Seekers in past generations might have found refuge in Rainer Maria Rilke or the Bible; I turned to the fatherly Peck, a remote but magnanimous presence who advocated self-discipline as the path to growth and happiness.

In the following years, I adopted other adolescent bibles, including Reviving Ophelia: Saving the Selves of Adolescent Girls (1994) by the psychologist Mary Pipher. The book decried a toxic, sexualised culture that, as Pipher wrote, ‘limits girls’ development [and] truncates their wholeness’, arguing for new cultural ideals valuing all young women’s gifts. I obsessively re‑read Ophelia in the spirit of self-help, to gain insight into my new, foreign-feeling body and mind, and was cheered by its message that my looks didn’t have to determine my destiny.

Standard-bearers such as Peck and Pipher made me feel that I could read my way to a better life. And as it turns out, my teenage conviction might not have been too far off the mark. Studies show that self-help books can resolve readers’ depressed moods, change ingrained thought patterns, and instill a renewed zest for life – as long as the advice within is scientifically sound.

For many patients, so-called ‘bibliotherapy’ seems to work as well as talk therapy or drugs such as Prozac. In an ideal world, says the psychologist John Norcross at the University of Scranton, self-help books would be tried early in the course of therapy; medications and other intensive treatments would be a last resort, reserved for more serious cases. With ‘psychosis, suicide, emergencies, you get immediately to the professionals. But for most people, why not start with a book?’

Its New Age veneer aside, the self-help genre has been evolving and thriving for millennia. Canonical books of all cultures are full of advice on how to live a more moral and satisfying life. The Upanishads, written by Hindu sages from an ethnically diverse Indian society, emphasised the necessity of treating others with tolerance and respect. ‘For those who live magnanimously,’ one book states, ‘the entire world constitutes but a family’ – advice that continues to help readers navigate today’s pluralistic India. The Jewish thinkers who wrote the Bible’s Old Testament in the 7th century BCE advised the narrow yet fulfilling path of strict adherence to God’s commandments, which seemed a fitting, unifying maxim for a people often beset by empires waging attack.

One of the earliest self-help guides in wide circulation was Marcus Cicero’s De Officis (On Duties), which the Roman politician wrote as a letter to his son. Cicero advised the younger Marcus to focus on meeting obligations to others, even if it required great sacrifice, and warned him away from shallow sources of gratification. ‘Brave he surely cannot possibly be that counts pain the supreme evil,’ Cicero wrote, ‘nor temperate he that holds pleasure to be the supreme good.’ This advice was rooted in Roman mos maiorum (ancestral custom), which emphasised loyalty to the empire above one’s own wellbeing – an ironclad moral code that fuelled the empire’s expansion for many years.

Centuries later, farmers, tradespeople and politicians laboured mightily to establish the still-young United States as an economic and social power. The new country’s citizens – who often lived off the land and took pride in stalwart self-sufficiency – found kindred spirits in self-help spokesmen such as Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, both of whom emphasised the sacrifice and struggle required to lead a meaningful life. ‘A great man is always willing to be little,’ Emerson opined in an 1841 essay. ‘When he is pushed, tormented, defeated, he has a chance to learn something.’

But by the mid-20th century, such self-abnegation was no longer in vogue. The prosperous Western economy was fuelling a generation of opportunists obsessed with maximising and flaunting their talents. A flurry of self-help books arrived to mark this transition, including Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People (1936).

Peck’s pull-no-punches opening sentence: ‘Life is difficult’ delivered an old message of discipline and restraint that was striking a new chord

Overnight, it seemed, personal agency and self-insight had become hot commodities – Freudian psychoanalysis was all the rage – and the new self-help titles initially seemed to offer a painless shot at a certain kind of lasting change, one based on consciously shifting your thought patterns. In the 1950s, Norman Vincent Peale’s The Power of Positive Thinking (1952) ruled bestseller lists with its promise that changing your inner monologue could boost the quality of your life. ‘Think positively,’ he wrote, ‘and you set in motion positive forces which bring positive results to pass.’

Thomas Harris’s classic I’m OK, You’re OK (1969) taught readers that when they put their minds to a realistic assessment of their personal worth, their lives and relationships would improve. Harris went as far as to say that many of the world’s problems could be better tackled if more people would speak to each other as reasonable adults, rather than unthinkingly allowing past childhood wounds to colour everyday interactions.

But as the era’s optimism and hippie excess faded, the tenor of self-help books shifted accordingly. The Road Less Travelled attracted a new, larger following in the no-nonsense 1980s, when the book hit the New York Times bestseller list for the first time. Peck’s pull-no-punches opening sentence: ‘Life is difficult’ delivered an old message of discipline and restraint that was striking a new chord.

These days, the self-help landscape seems to be split in two. On the one hand, the culture’s growing insistence on empiricism has left a clear stamp on the genre. Gone is the relatively freewheeling prose of How to Win Friends and Influence People and even The Road Less Travelled, which mainly espouse the authors’ personal views rather than particular scientific theories or schools of thought. They’ve been succeeded by books such as David Burns’s Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy (1980), Martin Seligman’s Learned Optimism: How to Change Your Mind and Your Life (1990), and Carol Dweck’s Mindset: The New Psychology of Success (2006), all of which cite one scientific study after another to bolster their recommendations for behavioural change. Many of today’s popular science books also advertise some sort of self-help takeaway. Malcolm Gladwell’s David and Goliath (2013), marshalls research describing how people can turn perceived weaknesses (dyslexia, childhood trauma) into strengths – a message tailor-made for self-improvement boosters.

Yet alongside the science-backed titles are those that peddle unsupported, even unhinged, claims. The bestselling The Secret (2006) by the TV writer Rhonda Byrne asserts that our thoughts send vibrations into the universe, which affects what happens in our lives. Good thoughts, the theory goes, create good outcomes, while bad thoughts create bad ones. ‘If any events or moments did not go the way you wanted, replay them in your mind in a way that thrills you,’ Byrne writes. ‘As you recreate those events in your mind exactly as you want, you are cleaning up your frequency from the day and you are emitting a new signal and frequency for tomorrow.’

Discerning researchers have started calling out the woo-peddlers in recent years, proving that a self-help principle’s popularity is no guarantee of its quality. In a 1999 study at the University of California, Los Angeles, students who visualised themselves scoring high on an upcoming test actually scored lower and devoted less time to preparation than students who did not visualise this outcome. And in a 2009 study, the psychologist Joanne Wood at the University of Waterloo found that people who had low self-esteem to begin with actually felt worse after parroting positive statements about themselves. So the power of positive thinking touted in books such as The Secret can be little more than a mirage. ‘Concluding that it works based on personal experience does not constitute rigorous research,’ Wood says.

Other advice commonly dispensed in self-help books – such as that venting your anger will diminish it or, if you’re feeling down, you should fill your mind with happy thoughts – have likewise failed to stand up to scientific scrutiny, as the psychologist Jeremy Dean points out. But as wayward as some self-help guidance can be, the genre also offers advice that is strikingly on the mark, even transformational. A handful of recent studies have underscored bibliotherapy’s potential to help create positive life change, as long as the book’s underlying tenets are sound. Depressed people in a 2010 trial at the University of Nevada thrived when they read Feeling Good, which navigates readers through the process – endorsed by cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) – of identifying their negative thoughts, assessing whether those thoughts were distorted, and if so replacing the thoughts with more logical, reality-based ones. Study participants in the bibliotherapy group showed as much mood improvement as members of another group who received ‘usual care’, including antidepressant prescriptions.

Self-help readers can maximise mental-health benefits by demanding at least some proof that the books they choose deliver on their promise

And in a 2013 study at the University of Glasgow, depressed subjects who used Chris William’s workbooks on overcoming depression were compared with subjects who received standard depression treatment, which included monitoring, antidepressants and referral to a psychologist. Four months after the start of the study, members of the bibliotherapy group scored several points lower on the Beck Depression Inventory than did members of the standard-care group.

Norcross endorses the idea that the right self-help books could serve some patients better than antidepressants or other psychoactive drugs, and without such common side effects as mood blunting, sleeplessness and sexual dysfunction. ‘Antidepressants are horribly over-prescribed. It’s particularly true for mild disorders that we know respond to self-help,’ he says. ‘We endorse a self-care approach. You start with the least expensive, most accessible materials.’

Norcross is well aware that the self-help canon is a lot like the patent medicine industry of the late 1800s, replete with products promising personal transformation, few of them offering proven effectiveness. So should self-help books be held to a scientific standard of proof? Norcross thinks so. ‘There should probably be some regulation. I’m one of those people that believes there needs to be an FDA [US Food and Drug Administration] equivalent for this.’

But Norcross knows it’s wishful thinking to expect clinical trials for self-help books, so he developed a less labour-intensive way to assess the books’ mettle. He surveyed a group of more than 2,500 psychologists, asking them to rate the effectiveness of self-help titles their clients had tried. Feeling Good emerged on top of the heap, with an average score of 1.51 on a scale from -2 (worst) to 2 (best). A handful of autobiographies scored almost as well, including William Styron’s Darkness Visible (1990) and Kay Jamison’s An Unquiet Mind (1995), perhaps because they outline concrete coping strategies while also helping mood-disorder sufferers feel they’re not alone.

Since Norcross conducted his survey, the UK’s National Health Service has given bibliotherapy a real-world road test. Through a programme called Reading Well Books on Prescription, patients with mild to moderate depression borrow library books such as Burns’s The Feeling Good Handbook (1990) or Frank Tallis’s How to Stop Worrying (1990) on doctors’ orders. Health authorities have endorsed all the books in the programme as offering evidence-based benefits, and it has good reviews from the reading public. In one survey of the Warwickshire region, three in four respondents ‘strongly agreed’ that Books on Prescription had improved their wellbeing.

Norcross’s research and the Books on Prescription results suggest that discriminating self-help readers can maximise mental-health benefits by demanding at least some proof that the books they choose deliver on their promise. This might mean that experts confirm a book contains valid principles, that the author cites peer-reviewed studies to support key points, or that the book has demonstrably helped a significant number of people. (Norcross’s studies have found no correlation between a book’s popularity and its effectiveness, so he warns against surface criteria such as sales numbers and celebrity endorsements.) Bibliotherapy is probably best undertaken with the guidance of a trained therapist – someone who can help readers assess how well the approach is working, offer advice on how to put self-help principles into practice, or recommend stronger treatment if appropriate.

When we pore endlessly over self-help titles, we’re groping for something more profound – to infuse our plodding lives with new texture and meaning

Once a particular book meets basic effectiveness benchmarks, the final verdict is more dependent on each seeker’s unique sensibilities. Self-help’s empirical shift has been a boon: readers can now proceed with more confidence that the end results will be worth the effort invested. But this shift has also given rise to many books that aim to help readers solve specific, bounded problems (depression, pessimism, relational conflict, social anxiety) rather than offering broader insights about how to live. Decades ago, when educated people regarded psychotherapy as a basic tool for carving out a fulfilled existence, it was only natural that self-help books such as Harris’s and Peck’s tracked the zeitgeist, guiding people to achieve the deep-rooted life satisfaction Aristotle called eudaimonia. Nowadays, therapy tends to focus more on healing well-defined mental pathology, and much recent self-help literature does the same.

Still, through all these changes in intellectual fashion, our desire for eudaimonia remains as strong as ever. In his writings, Norcross has pegged the self-help movement as part of the ‘human quest to understand and conquer behavioural disorders’, but many readers would find that description incomplete. When we pore endlessly over self-help titles, most of us aren’t just looking to resolve our problems one by one, with a to-do list mentality. We’re groping for something more profound – to infuse our plodding lives with new texture and meaning.

That’s why the psychologist Susan Krauss Whitbourne at the University of Massachusetts thinks it’s important to approach each self-help title with subjective attention to whether the content resonates on a deep level. ‘You want to look at: Is this something that’s going to work? What do I see in there that relates to me personally?’ It’s that sense of connection with a book, Whitbourne believes, that lets readers forge a therapeutic alliance with the author, boosting the odds that a literary meeting of the minds will spur genuine change.

Having dipped into self-help books with a strong empirical bent, I can attest that the benefits are real. I’m convinced that Feeling Good, with its well-vetted techniques to combat negative thinking, helped lift me out of a stubborn bout of depression. As someone prone to descend into spirals of dark thought, I also benefited from the advice of Burns’ colleague, psychiatrist Aaron Beck, who recommends keeping a ‘Daily Record of Dysfunctional Thoughts’. Writing down my exaggerated thoughts, identifying the errors they contained, and rebutting them with more logical thoughts helped keep my problems in perspective. The thought-challenging exercises reinforced a critical truth – I didn’t have to buy into everything my sometimes-overheated brain was telling me. My book-inspired course of self-therapy, I now believe, helped me as much as my sessions with a psychologist.

Even so, when I encounter a future crisis of the soul, the eminently practical Feeling Good won’t be the only book I reach for. I might also pick up The Road Less Travelled, with its time-tested wisdom about finding meaning in struggle. Or I might open Darkness Visible, the unforgettable testimony of a writer who found the way back from his own personal hell. When it comes to achieving eudaimonia, we are all lone cosmonauts fumbling our way. The literature we choose to guide us should supply proven advice we can trust. But it should also, as Franz Kafka wrote, be ‘the axe for the frozen sea within us’, bludgeoning us in ways that awaken us to the extraordinary.