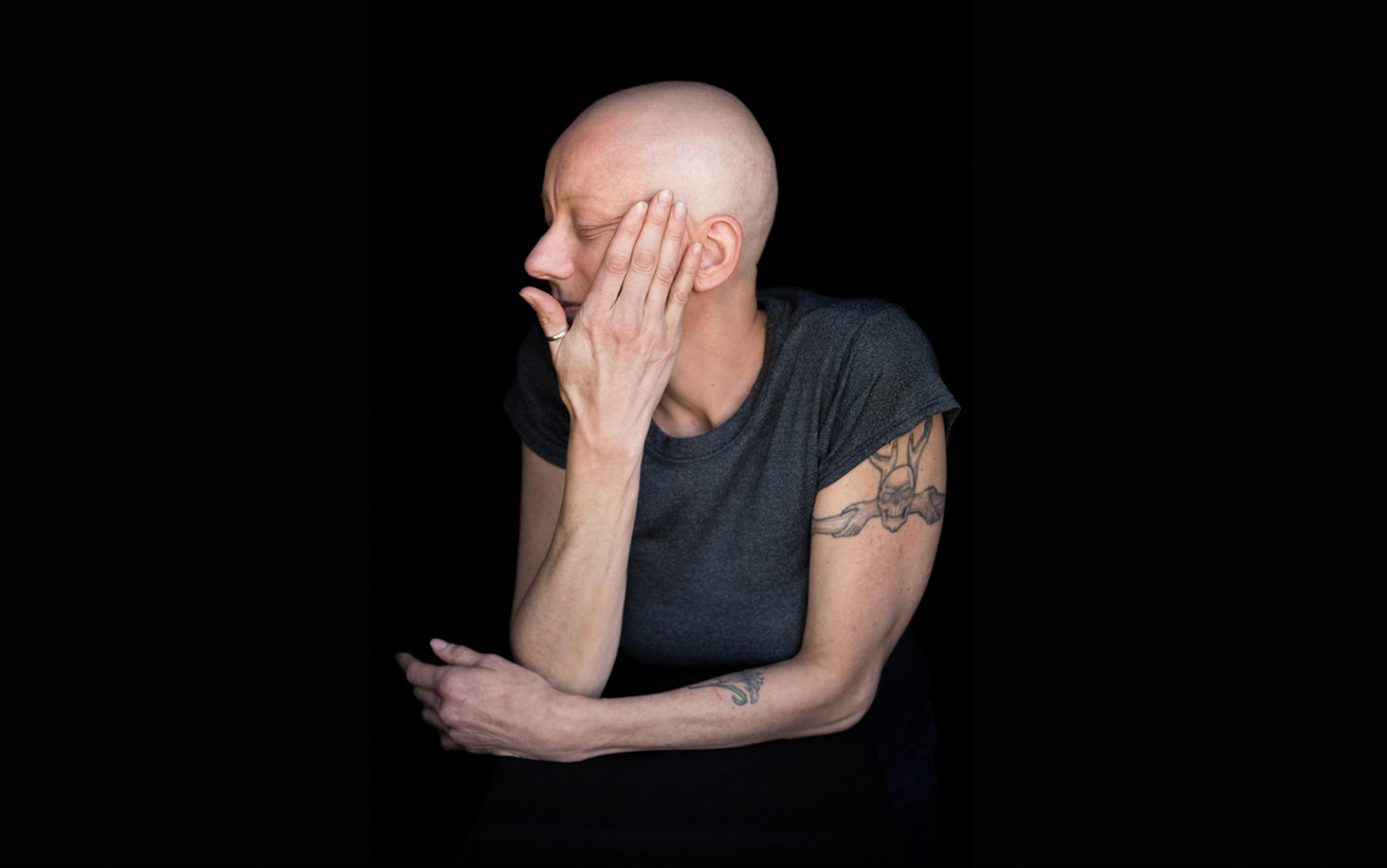

One evening, on the way home from a tiring conference, the philosopher Havi Carel, a professor at the University of Bristol, fell into conversation with her taxi driver. He was curious about the oxygen cylinder she carried. I have a chronic lung condition, Carel explained, the tubes of the cylinder hissing in the still night air. When they pulled up at her house, the driver, a devout Muslim, promised to pray for her. ‘I pity you,’ he said, kindly.

From pangs of compassion to undisguised horror and sheer coldness – the emotions that healthy people express in the presence of disease can seem like natural responses to its awfulness. Being unwell is usually treated as a categorically negative experience. Health is linked to ideas of agency, capability, freedom and possibility, standard entries in the roll-call of human flourishing. Illness, by contrast, comes with constraint, fragility, loss and restriction, the darker dimensions of what Susan Sontag called ‘the night-side of life’.

But is there something valuable about sickness? In Illness: The Cry of the Flesh (2008), Carel writes that her lung disease has brought ‘plenty of bad, but also, surprisingly, some good’. Philosophers tend to celebrate humanity’s sense of truth, goodness and beauty as our most defining and elevated features. But it might be truer to say that our existence is characterised by dependence and affliction. For sure, we think, speak, create and love, but we also age, sicken and eventually die. And as humans live longer, the prospect of many years of incapacity looms larger.

‘Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick,’ Sontag wrote in Illness as Metaphor (1978). ‘Although we all prefer to use only the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.’ If philosophy is about the pursuit of the good over the course of a human life, surely there’s an obligation to examine what’s worthwhile in the near-universal encounter with illness.

Bookshops are already filled with memoirs, diaries, accounts and letters by, for and about the ill. We seem to be living through a veritable ‘golden age of pathography’, as the historian Thomas Lacqueur observed recently. The desire for life lessons from writers in extremis is certainly part of the appeal. But Lacqueur notes that asking deep questions isn’t the same as being able to answer them, or even being able to write well. That’s true of thinking, too. So our enthusiasm should not be for pathography or even illness in itself, but for those aspects of the experience that promise to yield moral growth.

Am I rose-tinting or romanticising something that’s inherently unpleasant? No doubt such upbeat talk might comfort ill persons and their carers, you might say, but ultimately sickness robs us of what we need to live well. Epicurus advised that the main ingredients of a happy life are friendship, freedom and tranquility of mind – but these are often the first things to go during chronic illness. Former friends stop calling, freedom of body and mind disappear, and tranquillity is forever banished by pain and frustration. The writer Barbara Ehrenreich skewered the cultural placebo of positive thinking in her book Smile or Die (2009), where she attacked the ‘near-universal bright-siding’ of breast cancer in the developed world. It’s difficult to escape the triumphalist talk of illness as a journey, she says, destined to end in the revitalisation of one’s life, career, relationships and character – a narrative that excludes those who don’t witness much personal growth, or those who don’t recover.

Yet is it possible to defend the idea that illness can be a positive thing, while also acknowledging its destructive power? Yes: I think we can find a balance between bright-siding and despair. What I want to show is that illness can be edifying, for certain people – conducive to the cultivation and exercise of various virtues. If this is right, then it is indeed a life-transforming process that genuinely contains some good.

Illness isn’t absent from the history of philosophy. The Buddha arrived at the Noble Truth that ‘existence is suffering’ after encountering three men, one ill, one aged and one dead. Long periods of poor health can emancipate us from what St Augustine called ‘the frailty of the flesh’, with its lusts and hungers. Or force an appreciation of the brutal truths of the world, and ‘give birth to our thoughts out of pain’, as Friedrich Nietzsche claimed. But the problem with these suggestions is that they rely upon specific conceptions of what it means to be human – as ‘conditioned’ beings in a world of impermanence, say, or as ‘fallen’ creatures aspiring to union with God. Some ill persons might subscribe to these, but not all do, could or should.

Even in the absence of complex philosophical or theological systems, personal testimonies of illness often speak of it as morally improving. There is talk of having learned important lessons about life, ‘deep truths’ essential to living well that only charged confrontations with one’s felt mortality can provide. Many ill persons talk of becoming kinder, gentler, more appreciative, less egotistical. The thought is that being unwell somehow enabled the person to acquire or develop these qualities.

The body is central to this connection between illness and virtue. Carel distinguishes between the ‘biological body’ (the organism as described and treated by biomedical science) from the ‘lived body’ (the entity we experience as the self, and with which we have a troubled and changing relationship). No one experiences one’s own body as a collection of flesh, bones and fluids, even if that’s how medicine tends to view the matter. Instead, one’s body is lived. It is not an incidental component of our personal identity, but the locus of our agency, activity and concerns.

a life consists of thousands of small things, and each of these small acts is its own modest opportunity for the exercise of virtue

When you are healthy, the biological body effortlessly realises your commands, and offers few obstacles to your will. But in illness, the body strains, resists. Desires cannot translate into action and the world seems to wither, becoming uncanny and oppressive. When you are unwell, you understand, in a radical way, how your experience is contingent upon your embodied self. A medical description of the dysfunctions of the biological body does not exhaust what it is like to be ill, says Carel. No one experiences only the physical reality of diminished lung capacity. They feel frustration at being unable to quickly nip upstairs, or anxiety at everything seeming to shrink and cave in on itself. Dreams and ambitions dissolve as the fragility of one’s aching lungs protest. Sickness is not just the experience of pain and malaise, but also of acute vulnerability in a hostile world that refuses to accommodate itself to your struggles.

Illness, then, is the seam that runs between the biological and the lived body. Disease is a dysfunction of the biological body, while illness is the felt experience of those dysfunctions, of the cold realisation of one’s mortality and fragility. But acknowledging this link can be an opportunity for moral growth, Carel argues. When disease splits apart the ‘flawless correspondence’ of the two bodies, a person comes to realise a set of truths about her being-in-the-world. This demands a host of different sensibilities and responses, even when medical treatment is successful. Chemotherapy might remove a cancer patient’s tumours, but not her sense of alienation from a body she now feels has ‘betrayed’ her. Surgery can restore an organ, but not a lost sense of the world as a space of possibilities. This is where the experience of illness might afford distinctly moral goods.

Adaptability and creativity are two qualities that Carel’s own illness brought to the fore. She avoids steep gradients and multiple trips up and down stairs. She finds new routes for walking the dog, and learns to schedule all the week’s meetings for the same day, at the same end of the university campus. Such exercises are inextricable from and internal to the experience of her condition, Carel says. Adaptability is a direct response to her changing bodily capacities, while creativity takes place within her practical and social world conditioned by her lung disease. This daily rhythm might lack some of the metaphysical drama described by the Buddha, Augustine or Nietzsche. But a life consists of thousands of small things, and each of these small acts is its own modest opportunity for the exercise of virtue.

Critics of the claim that illness can be edifying fall into two groups. The writer Gina M Shaw, who survived breast cancer, argues that talking about the redemptive potential of illness creates perverse incentives to induce, exacerbate or prolong disease. Shaw derides talk of cancer as a ‘gift’, because such language disguises the horrible physical and emotional realities of life with cancer. A gift gives, whereas cancer, she says, is ‘the thief that keeps on taking’. Since illness will take more and more from a person the longer and the worse they have it, anything that might smear a positive gloss on the experience – of virtues, truths or whatever – should be rejected.

Learning to be rude was an essential strategy for shrugging off the insensitive stares and intrusive questions of strangers

It’s true that some people have pushed for the active pursuit of illness. Diogenes, one of the Cynics of ancient Greece, reportedly rolled in hot sand in summer and walked barefoot through the snow in winter, insisting that virtues such as self-sufficiency and discipline could be developed only by enduring hardships. (The cause of his death was said to be either eating raw octopus, an infected dog-bite or holding his breath by choice.) Nietzsche, who admired the Cynics, said that, while great suffering might not make us better, it certainly makes us deeper – and is the ultimate liberator of the spirit, exposing our true ‘energies’ occluded by the ease of wellbeing.

But few philosophers seriously entertain such austere notions of what moral cultivation looks like. The virtues that Nietzsche and the Cynics prized were muscular, martial ones, such as courage and self-control – while today, ill people talk just as frequently of learning patience and empathy. More broadly, the fact that illness can be edifying does not, in itself, mean one should seek out or worsen disease. While virtue matters, so does health, and a prudent person does not necessarily seek the former at the expense of the latter.

A second set of detractors observes that illness does not make everyone morally better. Illness can edify, but it can also tarnish. It can make people less kind, less patient, more self-absorbed. It might build vices, not virtues, and erode what virtues we had in the first place. The psychotherapist Kathlyn Conway, in her memoir Ordinary Life (1997), describes how, as the symptoms of her breast cancer grew, her compassionate concern for others shrunk – not least because coping with illness demands so much energy. Certain vices might even be necessary in these circumstances. Carel found that learning to be rude was an essential strategy for shrugging off the insensitive stares and intrusive questions of strangers. If so, talk of the ennobling effects of disease might just make the whole experience harder.

So am I just putting a fresh burden on the shoulders of the unwell by talking about the morally transformative powers of illness? Such projects are difficult enough at the best of times, let alone when one is struggling like a ‘half-crushed worm’, to use Simone Weil’s vivid description of suffering and sickness. The expectation that she be optimistic enraged Christina Middlebrook and turned her ‘ugly as Medusa’, she wrote in Seeing the Crab (1996), her memoir of dying, published before her death in 2009 from metastatic breast cancer.

It’s true that the ideology of ‘positive thinking’ condemned by Ehrenreich and others ignores the complexity and diversity of what it’s like to be ill. Sometimes the end is restored health. But sometimes it is a painful death. Sometimes one adapts with courage, but sometimes one falters and loses all hope. My approach appears to imply that those who weren’t edified by their illness have somehow failed, that perhaps they regain their health but not a set of consolatory virtues.

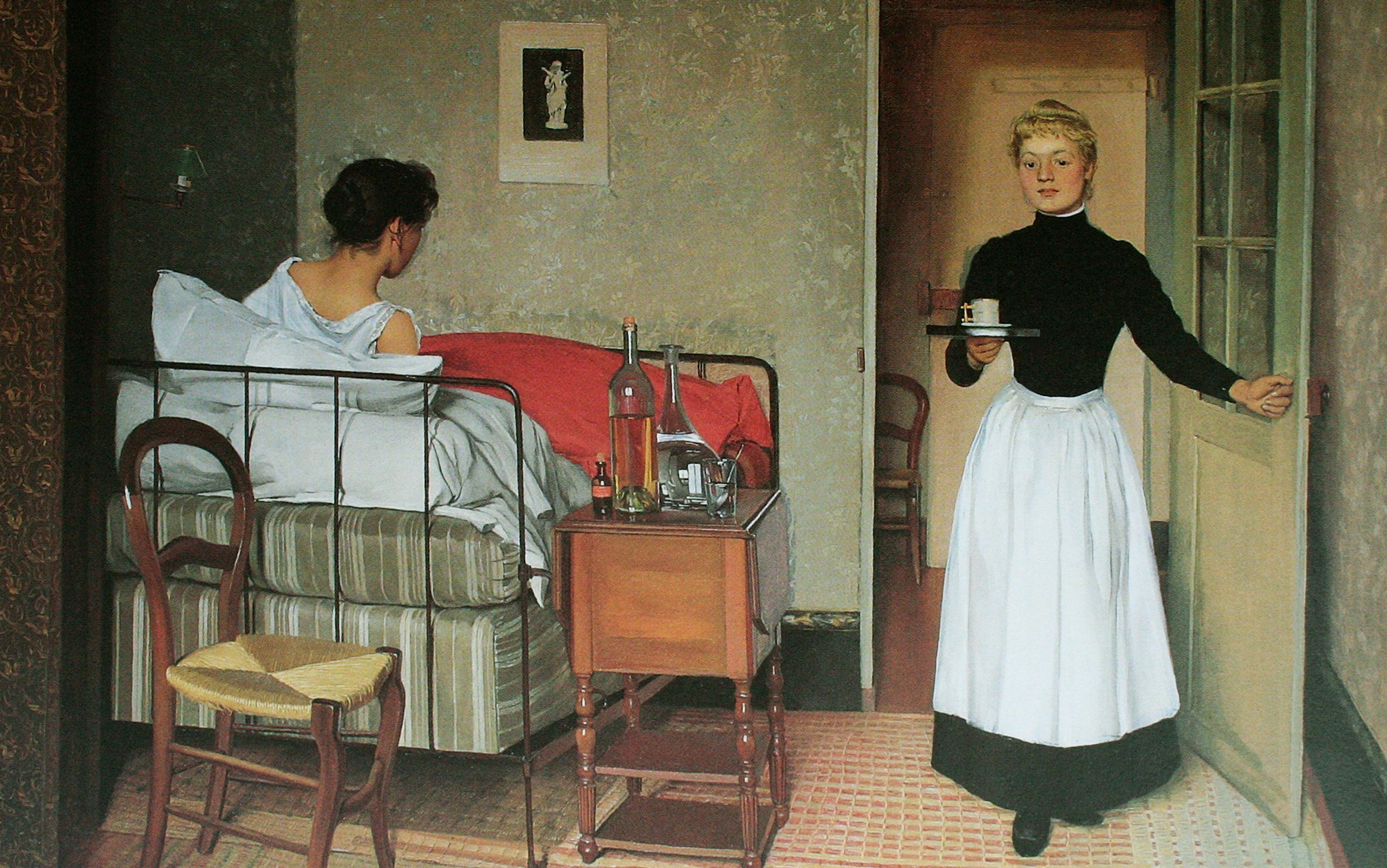

Yet I think we can reclaim the virtue-enhancing potential of illness, on two conditions. One is to recognise that edification is not always possible. Clearly, unearthing virtue in times of trial is a complex process, dependent on many things – the nature of the illness, one’s temperament, the sorts of practical and social support available. This last factor is particularly significant. As the ancients knew, cultivating personal virtue is a communal activity, because we learn about and refine our character through encounters with other people. (Think of Carel’s virtues of adaptability and creativity, both easier to develop through cooperation.)

It would be a terrible failure of empathy to demand that everyone explore the character-building possibilities for illness

So the extent to which illness can create a space for personal growth, and the extent to which it is destructive and alienating, depend in part on the wider social and political context. The testimonies of many ill persons – often poignant, often angry – perhaps indicate that the moral and social culture of Western societies is not particularly conducive to edification. Recent moves in the UK, for example, to cut funding for mental-health support groups, to demonise ‘sick-noters’ and ‘benefit scroungers’, and to tighten the criteria for obtaining disability allowance, are unlikely to help ill people find meaning in their experience.

Another humane way to retain the value of illness is to not insist that sick people seek edification. Some might choose to respond to serious illness by looking at it as a challenge, a battle to be won, an opportunity to grow. But others hate such talk. They see illness as something to be coped with or endured, an unwelcome journey to complete, rather than a race to win. It would be a terrible failure of empathy to demand that everyone explore the character-building possibilities for illness.

Empathy is, in fact, the virtue most people lack, according to Carel – especially the obliviously healthy, who take the cooperation of their body for granted. Cultivating empathy for the experience of illness means learning to think about it ‘from the inside’, from within the lived body of someone who is unwell, rather than treating that condition as a mere biological or medical problem. This means trying to see the perspective of a person battling, not only against disease, but also against others’ lack of understanding of its relentless demands – bodily, psychological, emotional and social.

Much of what is said about the philosophy of the good life presupposes health is a prerequisite. But if illness is a constitutive feature of the human condition, we must take a wider view of how the dependent, afflicted and vulnerable can flourish in the face of adversity. Looking seriously at the edifying potential of illness is a step in the right direction.