One day this fall, I came home from work and found, among the usual pile of bills and flyers and mass mailings pulled from the mailbox, a crisp white letter from the hospital where I’d recently had a mammogram. I am used to these letters: one appears every year, a week or two after my annual appointment, confirming my test results were normal, and that I should call to schedule another mammogram in a year.

This year the form letter deviates from script. ‘Your test results were incomplete,’ I read aloud. ‘We recommend you come back in for further imaging.’ My husband looks up from the dining room table where he’s working. ‘Is this something we should worry about?’

The modern English sense of the word ‘worry’ – to feel ‘mental distress or trouble’ – is of relatively recent origin. The original Old English word was much bloodier: wyrgen, to ‘strangle’, or to kill by biting and shaking an animal by the throat. It is the wolf going for the jugular, shaking the lifeblood out of its quarry; the dog incessantly worrying his bone. Other English words denoting mental pain or obsession have similar roots in animal acts of eating or attacking: to fret, cognate of the German fressen, ‘to eat up’. There is also gnaw and, relatedly, gnash from Old English gnagan. It comes to us via the proto-German verb gh(e)n: onomatopoeia for the act of gobbling up by little bites. We are consumed by grief; gnawed by remorse; eaten up with worry.

I glance at the diagnostic code at the bottom of my mammogram letter – ‘BI-RADS 0’ – and quickly google it. ‘A score of 0 indicates an incomplete test. The mammogram images may have been difficult to read or interpret,’ I learn. ‘Oftentimes, women 40 years and older receive scores ranging from 0 to 2, indicating normal results or that abnormal results are benign, or noncancerous.’

‘No,’ I reassure my husband. ‘No need to worry.’

Still, I dutifully return for a second test. After the mammogram, the nurse takes me to a room where I’ll have an ultrasound. I’ve complimented the staff on the upgrades they’ve made since my last visit. In the waiting room, I find iced cucumber water in a glass dispenser and, in the examining room, fluffy terry robes in place of the usual pale-blue paper slips. There is even a bowl of fruit – apples and oranges – cheerily posted on a table outside the changing stalls. ‘I feel like I’m at a spa,’ I quip to no one in particular.

Prone on the examining table, I slip my left arm out of the robe and feel the warm silicone gel slide over my breast and chest. Then the wand, swiping back and forth against my skin. The image on the screen, grainy black-and-white and grey, could be a picture of anything: riverbed, water rushing over rocks; the smear of a galaxy; the salty sea of a womb quickening with life.

As it happens, it is none of the above; rather, a clump of cells the radiologist doesn’t like the look of. A white smudge nestled against the striated black soup. It is round and smooth on one end but juts out with a jagged claw on the other. ‘What is it?’ I ask the doctor.

‘You see, a cyst or a benign mass would be perfectly round – like an egg, or a pea,’ she begins. ‘This ragged edge’ – pointing to the claw – ‘that’s what makes it suspicious.’

‘Is it cancer?’ I ask. It is only now occurring to me that it might be.

‘I’m so very sorry,’ she says.

Cancer has always been imagined as a biting, grasping, greedy beast. Hippocrates (or one of his students) is thought to be the first to name the disease karkinos, or crab, as ‘its veins are filled and stretched around like the feet of the animal called crab’. It was an image that would stick, embellished by physicians more deeply and vividly ever after, as the scholar Alanna Skuse outlines in her book Constructions of Cancer in Early Modern England (2015). Like the crab, cancer was tenacious. ‘It is very hardly pulled away from those members, which it doth lay hold on, as the sea crab doth,’ remarked one 16th-century physician. There was no use in cutting away the tumour, just as there was no forcing a ‘Crab to quit what he has grasped betwixt his griping Claws,’ despaired another observer. Cancer the disease was as sneaky as its namesake. ‘It creeps little and little,’ noted one medieval commentator, ‘gnawing and fretting flesh and sinews slowish to the sight as it were a crab.’

Cancer’s gnawing behaviour led early physicians to compare it to a worm as well as to a crab. The medieval name for the plant-devouring green caterpillar, canker worm, derived from one such metaphorical leap from biology to botany: as cankers on the skin, so cankers in the bud. And just as malignant larvae in plants had to be destroyed before they blighted the flower, so one had to ‘sley the worm’ of cancer when it chanced to rear its head in human flesh. This worm could be quite literal; the 17th-century surgeon Pierre Dionis surmised that cancer was nothing more than a ‘prodigious Multitude of small worms’ infesting its host. A common medieval remedy, the so-called ‘meat cure’, involved laying slabs of fresh chicken or veal on the ulcer, by which to lure the creature out. Could the canker worm be convinced to ingest the decoy flesh, the patient might be spared.

The body obliges, unwittingly nourishing the assassin nestled in its heart

One tale that found its way into an early 18th-century medical manual – acknowledged by most to be apocryphal – told of a cancerous ulcer inhabited not by worms, but by a wolf. A witness vowed that once, in applying a slice of meat to a patient’s tumour, she saw that ‘a Wolf peeps out, discovering his head, and gaping to receive it.’ The existence of a literal cancer-wolf within the body might have strained belief. Still, the analogical force of these animals was strong: both the worm and the wolf made their way into the apothecary’s shop as treatments for cancer. Following the homeopathic principle that ‘like cures like’, one early recipe for a cancer-fighting salve included powdered ‘wolf tongue’ among its ingredients. More common were tinctures that called for ground and powdered worms. Worms harvested from tree bark, then ‘stamped and strained with Ale’, were brewed into a potion eagerly quaffed by cancer sufferers.

Early modern physicians were not entirely wrong in imagining cancer as an eating disease. As the cancer grows, it needs more food. The cancer cells release chemical signals to the surrounding capillaries and veins coaxing them to create new blood vessels, to branch out like a coral forest, delivering life-giving nutrients and oxygen to their blooming colony. The body obliges, unwittingly nourishing the assassin nestled in its heart.

Hippocrates’ karkinos would extend its spindly legs outward through the centuries, its metaphors spreading like creeper vines across the pages of the medical texts that sought to describe and contain it. Cancer is a crab; no, it is a worm; no, it is a wolf. As if the symbol that originally stood in for the disease could not help but mirror the proliferating, perambulating logic of the very thing it named. Words (cells) gone dizzy with division, malignant blooms without borders.

After the mastectomy, after the biopsy, the surgeon tells me she excised the one visible tumour but that the tissue extracted still showed a ‘positive margin’, meaning that they discovered additional cancer cells – ones that hadn’t shown up on the mammogram – at the edge of the cut tissue. ‘The margin is described as negative or clean when the pathologist finds no cancer cells at the edge of the tissue, suggesting that all of the cancer has been removed,’ says the US National Cancer Institute’s dictionary of cancer terms. ‘The margin is described as positive or involved when the pathologist finds cancer cells at the edge of the tissue, suggesting that all of the cancer has not been removed.’

The scalpel is clean and gleaming and precise, everything the cancer is not. It will slice through and extract the cells, like a paring knife scooping a bruise out of a fruit. But my cancer has evaded both the X-ray and the knife, the eye and the blade: a slip of a fish sliding off a hook, a mercury bead scattering at the touch of a finger.

Now the fugitive cells could be anywhere, or nowhere. They elude detection. Absence of ocular proof is no reason at all to believe that the cancer isn’t there; on the contrary, absence multiplies the paranoid suspicion of its lurking presence, as Othello well knew. The surgeon sends my cancer cells back to the genetics lab to measure the chance of recurrence.

So we will bring in the big guns, my doctor tells me, the chemicals and the lasers, to roust this worm from its secret perch. ‘O Rose thou art sick,’ writes William Blake in Songs of Innocence and Experience (1794). ‘The invisible worm,/That flies in the night/… Has found out thy bed/Of crimson joy:/And his dark secret love/Does thy life destroy.’ I imagine the maniac cells coursing through my veins, caustic threshing of rosy flesh, seeking out the crimson bed of my liver, my bone marrow, my brain – plotting their return.

We couldn’t help but laugh at nature’s indifference to our tender rite

A memory: the summer we went to Crete, my daughters and I gathered shells at the sea’s edge. They were beautiful, flashes of white against a bank of shiny dark pebbles. We found miniature conch shells, pulsing orange and pink; lavender sea urchins the size of a baby’s fingernail. Their spongy inhabitants had long since melted back into the saltwater whence they came, leaving behind these bony memorials. When we got home and spread the shells out on the grass, one of them began to shake, made a hairsbreadth lurch, started to crawl: one among the haul was not mineral but animal; not husk but home. A tiny hermit crab had donned a stranger’s skin, a twice-born shell. Its ragged claws peeked out and immediately retreated upon the lightest touch.

The next day when we woke up, the shell was still: its inhabitant tucked up inside, its fortress become a tiny tomb. My daughter wanted to give him a sea burial. She built a miniature raft of driftwood, bound together with some old string we found in the house we were renting. She wrapped the dead crab in a leaf and lodged him in a crook of the boat.

That night after dinner in town, we walked to the beach. My husband lit the funeral pyre with a match and, cupping the flame with his hand, waded knee-deep into the wine-dark sea. He placed it in a trough between two cresting waves.

He had no sooner let go than a foam-flecked swell swallowed the bark whole, downing it in one unceremonious gulp. From the shore, we couldn’t help but laugh at nature’s indifference to our tender rite. A message from the watery waste before us: no, your creature-kindled warmth is no match for me.

Cancer forces you to recalibrate your sense of danger, and the direction from which it might come. Cancer is not the wolf at the door, begging entry of the three little pigs. No; this sickness is an inside job.

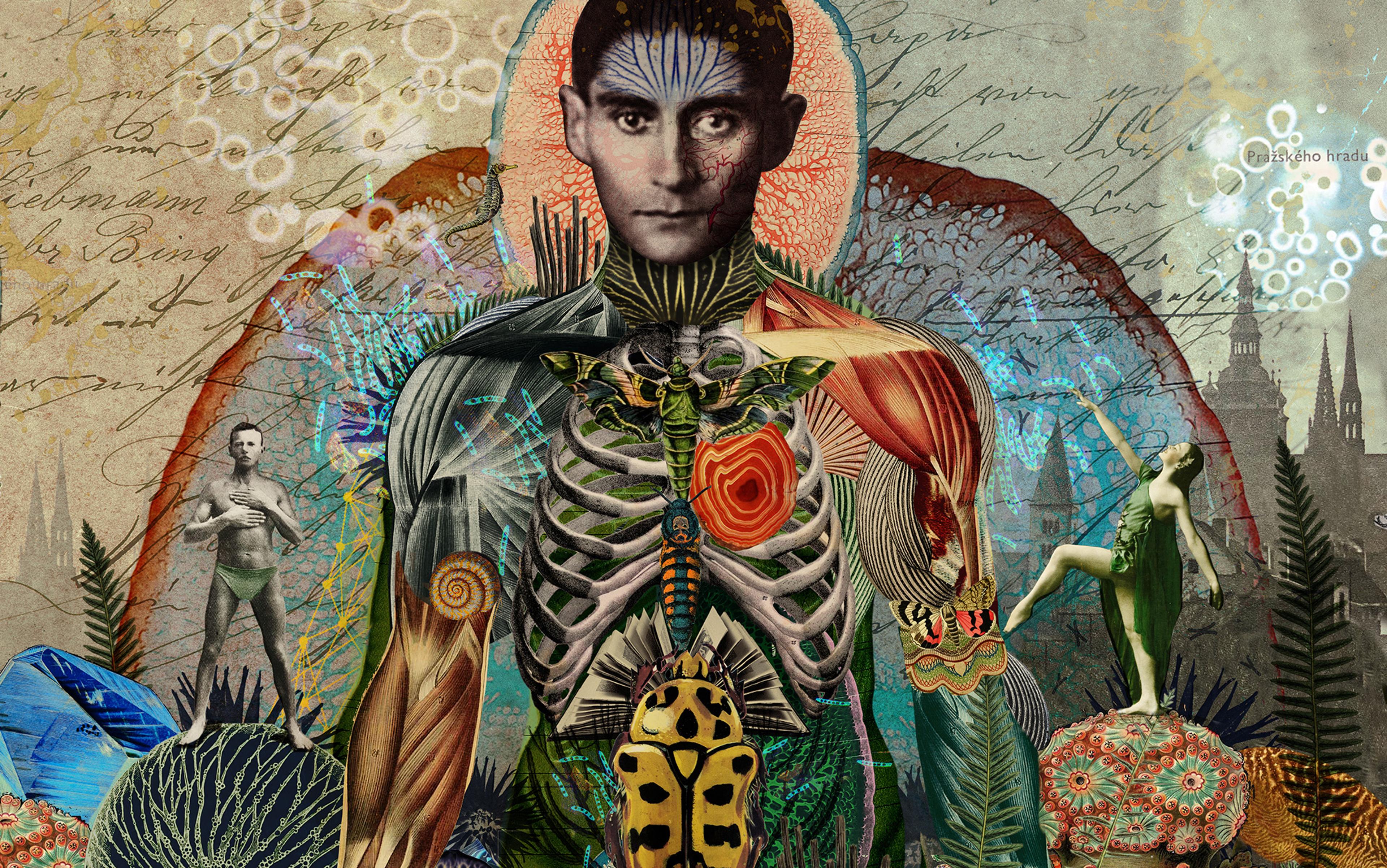

Franz Kafka’s story ‘The Burrow’ is told from the perspective of a forest animal who has crafted a perfect underground hideout to protect him from predators. His is a world of frantic quick strikes, snatching jaws, eat-or-be-eaten. He muses on the less fortunate animals above ground, ‘poor homeless wanderers in the roads and woods, creeping for warmth into a heap of leaves or a herd of their comrades, delivered to all the perils of heaven and earth!’ Tucked away in his burrow he is safe; all is still.

Then one night he is awakened by a small whistling noise coming from within the walls of his home, almost nothing, ‘audible only to the ear of the householder’. He scratches in the direction of the whistling, rifling through the soil, breaking up the lumps into tiny particles – ‘but the noisemakers are not among them.’ He steels himself; he will be methodical. ‘I shall dig a wide and carefully constructed trench in the direction of the noise and not cease from digging until … I find the real cause of the noise,’ he determines. ‘Then I shall eradicate it, if that is within my power, and if it is not, at least I shall know the truth. That truth will bring me either peace or despair, but whether the one or the other, it will be beyond doubt or question.’ But such clear-cut knowledge is not to be his. The noise seems to come from nowhere and everywhere at once. No matter where he digs, the noise persists: patient, steady, undeterred. It neither advances nor recedes. This is a threat that refuses to give him a toehold, a purchase, a vantage from which to confront it.

To accept our animal self means to look worry clear in the eye, to size it up, and then choose to wait

The outside world is a noisy, chancy, clanging place, chock-full of danger. This much I acknowledge. As the burrower observes, ‘danger lies in ambush as before above the moss’. But from now on, I know – like Kafka’s animal – I will always be listening instead to that ghost of a whisper coming from inside my own walls.

Still, most days I don’t worry. To be worried to death is, quite literally, the fate of all flesh. The fretting agent might differ, but we all know how it ends: our animal cells, the sick and the well, will sooner or later dissolve back into earth, be eaten up in their turn. To accept our animal self means to look worry clear in the eye, to size it up, and then choose, instead, to wait.

When I’m feeling well, I swim outside in the Los Angeles dusk. The pool is warm, 85 degrees Fahrenheit to the ambient January 60something of this desert climate. One night recently, after I had finished my laps and popped my head up above the blue surface of the water, I heard clutches of birds singing in the surrounding bushes. A low chuck-chuck-chuck: a three-note trill, an impossibly dulcet sound that punctured the air like a plucked harp string, rising above the chatter. This wasn’t a settling-down-to-sleep song. It was a raucous, drunken chorus, like the birds had forgotten what time it was, like the Earth was spinning backwards on its axis. I crouched in the water, still except for my breath, and listened as they poured out their silken throats into the gathering darkness.

To wait is the most anodyne of verbs, a familiar no-man’s land of lost or useless time that threads itself through daily life: we wait in line at the pharmacy; we wait for a thundershower to pass; we wait for a friend to call. This waiting is empty time, a lull in the forward rush of life, of getting things done. It stops us in our tracks and temporarily suspends our power. It can make us feel annoyed or helpless. ‘There’s nothing to do but wait,’ we tell ourselves. Then the prescription is delivered, the sky clears, the phone rings – and off we go again, our power to do and to be mercifully restored.

But there is a larger waiting, a cosmic waiting that precedes and cradles within itself all the other times and modes and tenses of being. It tells us that our puny power to do and to be in this world is the exception, not the rule. Waiting is not the suspension of human business-as-usual, but rather the oldest and most elemental form of time. The modern meaning of the English verb to wait in its most banal sense, ‘to remain stationary’, derives from a trio of Old English verbs: waeccan, ‘to keep watch’; wacian, ‘to be awake’, and wacan, ‘to become awake, arise, be born’. This is waiting as sheer presence, watchfulness, the quickening spark of life. It is ruach elohim, the breath of God, moving over the face of the waters the instant before creation: time before time.

To wait in this way means simply to bear witness to breath, the gift of wakefulness, as it lights up (here, now) in this accidental vessel that is myself. It asks nothing more of the time that remains.