Donald Trump’s presidency has made the dominance of strongmen elsewhere only more vivid: in Russia, Thailand, Hungary, Brazil, Nicaragua, the Philippines and many other countries. Since around 2016, the question of where the strongman phenomenon comes from has been a constant issue for political theorists. What allows these men to rise? And why now? The answer is often wrapped up in some idea of ‘populism’. ‘The people’, so the thought goes, have gained control of ‘the elites’. This is a view of populism as essentially thuggish and anti-intellectual. The people are insurgent, and with great bluster and bravado the leader claims to speak for them.

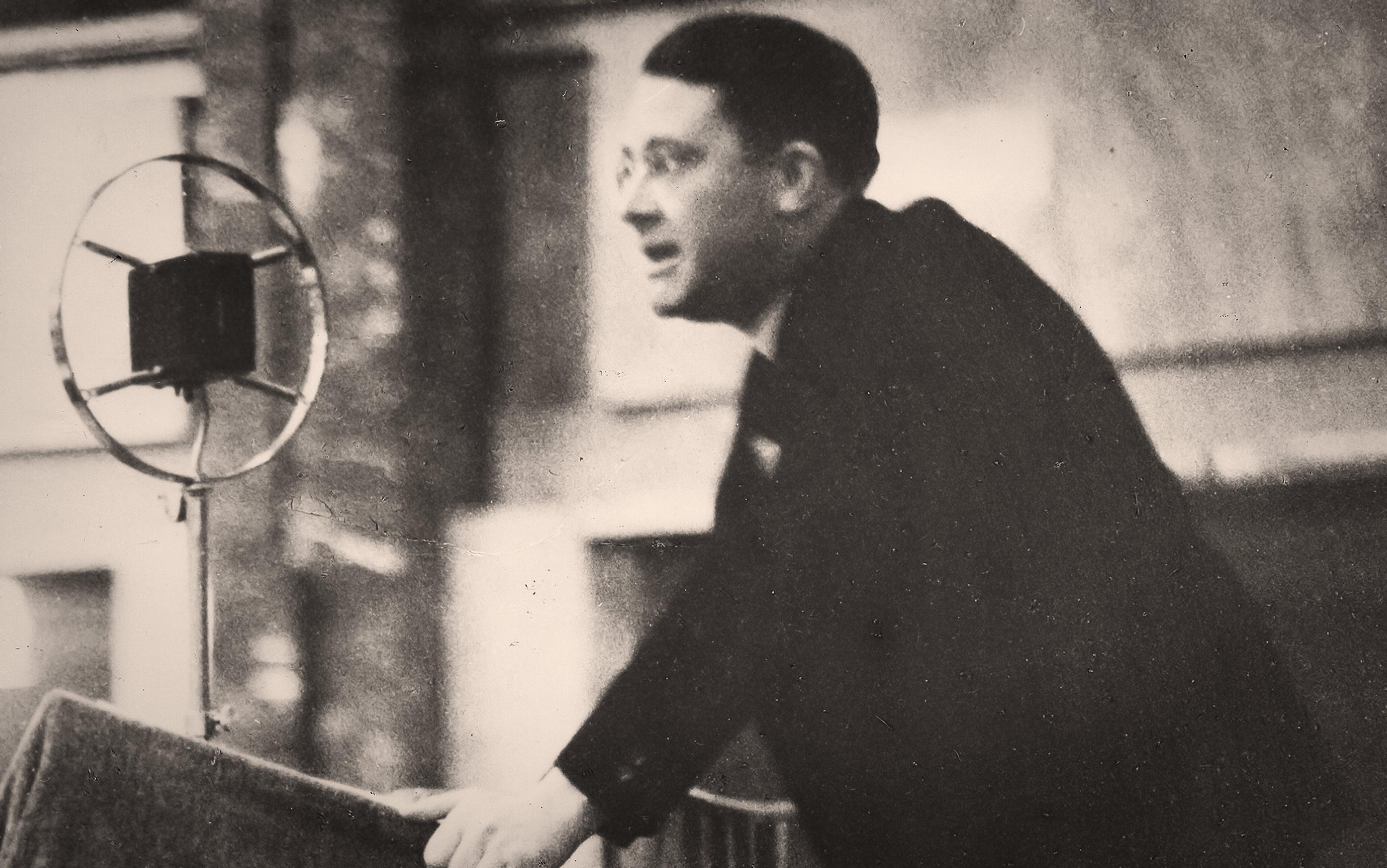

But there is, in fact, a robustly intellectual foundation for strongman politics. Populism is not just a bull-in-a-china-shop way of doing politics. There is a theoretical tradition that seeks to justify strongman rule, an ideological school of demagoguery, one might call it, that is now more relevant than ever. Within that tradition, one thinker stands out: the conservative German constitutional lawyer and political theorist Carl Schmitt (1888-1985). For a time, he was the principal legal adviser to the Nazi regime. And today his name is approaching a commonplace. Academics, policymakers and journalists appeal to him in order to shed light on populist trends in the US and elsewhere. A recent article in The New York Review of Books argues that the US attorney general William Barr is ‘The Carl Schmitt Of Our Time’. The Oxford Handbook of Carl Schmitt (2017) came out in print the year after Trump’s election. After decades as a political rogue, forced to launch his attacks on liberalism from the sidelines, Schmitt’s name has returned to prominence.

He was the great systematiser of populist thought, which makes him useful for understanding how populist strategies might play out in politics, as well as in the legal/constitutional sphere. In The Concept of the Political (1932), he claimed that fundamental to ‘the political’ is the distinction between friend and enemy – who is in the political community, and who is out – and that what matters in politics is only whether some ideological proposal stands a chance to be successful, given the historical context.

In the Weimar period, during which a rickety republic governed interwar Germany from 1918 to 1933, Schmitt took it as a basic fact that democracy was the sole principle of legitimacy capable of garnering mass support. So, for this supreme anti-liberal, the challenge of the times was to reinterpret democracy into authoritarian terms. Any ideology based on an idea of the ‘substantive homogeneity’ of the nation would do – a secular substitute for the religious basis on which political legitimacy had been founded in the past. Schmitt yoked that idea to his claim that the sovereign is ‘he who decides on the state of exception’. Sovereignty is revealed in a situation of crisis, when the identity of the political community is at stake. In the circumstances of post-First World War constitutionalism, Schmitt located the bearer of sovereignty in the figure at the apex of the executive branch of government (in Weimar, the president of the Reich) because only he could rise above the fray of partisan politics and represent the political community.

Now, not only did Schmitt achieve prominence as a legal adviser to the Nazis, but he had no principled basis for rejecting Nazi ideology since it represented a powerful form of anti-liberalism and could be seen as the realisation of the ‘true’ form of democracy, if the latter consists in the unity that arises in following the leader who embodies the authentic community. He was a virulent antisemite as well. But it is a mistake to describe him, as contemporary discussions often do, as a ‘Nazi legal theorist’. His most important contributions were made during the Weimar Republic, when he was allied to conservative forces deeply opposed to the Nazis; and he could subsequently never become enough of a Nazi to stay in their favour for long.

The identification with Nazism obscures Schmitt’s argument, couched in constitutional terms, which concludes that the chief executive is the real ‘guardian of the constitution’ and so the ultimate legal authority. This argument is the most significant component of Schmittean logic. It is important to understand it because the policies of today’s strongmen are often criticised as an assault on the rule of law. However, their legal adviser and the judges they appoint to their appellate courts understand their approach to law – one that gathers ever more power unto the leader – as constitutionally required, not wilfully against the law. While these lawyers are often deeply opposed to the administrative state because they regard it as the legal arm of the welfare state, they venerate the executive political office at the apex of the state hierarchy. Their mindset is the product of a highly successful attempt to educate conservative lawyers in such views.

This is most prominently displayed in the US by the activities of the conservative Federalist Society, with its power to steer Trump-era judicial appointments. In the United Kingdom, the Judicial Power Project has similar aims, and the ear of the wannabe strongman Boris Johnson’s government. It informs the impending reforms to reduce the judiciary’s authority and marginalise the impact of the European Convention on Human Rights until such time as the UK exits that convention, by which it is still bound, despite its exit of the European Union (EU). The project is hosted by Policy Exchange, a conservative, anti-European and anti-human-rights thinktank that refuses to reveal the sources of its funding.

In this light, it is important to examine both the legal component of Schmittean logic, as well as the position of fellow lawyers who exposed Schmitt’s argument as pseudo-legal, and as deploying legal terminology with the aim of exploding liberal-democratic constitutional order. The best window is a court case of 1932, decided at a time when Hitler’s ascent to power still seemed not only preventable, but unlikely.

At issue in the case Prussia v Reich was the federal government’s ‘coup’ against the Land (state) of Prussia, in which the Reich took over the Prussian government by invoking Article 48, the emergency powers provision of the Weimar Constitution. By the time of the coup, German democracy was in trouble. The collapse of a grand coalition government in the financial crisis of 1929 brought an era of increasingly authoritarian rule by presidential decree, made possible by the peculiar place of the president in the Weimar Constitution. The exercise of these powers, given to the president by Article 48, required the countersignature of the cabinet; and the cabinet, while appointed by the president, had to enjoy the confidence of the Reichstag (the federal parliament). The president also had the power to dissolve that body, a power limited only by the vague requirement that he could do this ‘only once on the same ground’. This power, combined with the power to appoint the cabinet, meant that the president could for 60 days ensure a cabinet that would give him the requisite countersignature and that didn’t have the confidence of the Reichstag simply because it was not in session.

Prussia – the largest Land in the federation – was the bastion of social democratic resistance to the conservative federal cabinets of the 1930s. The coup was at the behest of the chancellor, Franz von Papen. He had prepared the way by lifting a ban on street demonstrations in Prussia from the Nazis while maintaining one on the communists, a tactic that succeeded in provoking lethal violence on the streets of Berlin and elsewhere, which the Prussian police struggled to contain. On the pretext that the Prussian government was failing to maintain order and fulfil its constitutional duties to the Reich, a decree was issued under Article 48 that ousted the Prussian government and put its machinery in Papen’s hands. The coup was the first move in a plan to get rid of the social democrats, to be followed by the communists, while Hitler would be tamed by drawing him within the control of an increasingly authoritarian cabinet. The strategy would be complete once the cabinet, having eliminated all internal opposition and obstacles (including the Reichstag), ruled Germany by decree.

At the time of the coup, the Prussian government – in which the Social Democratic Party was the dominant faction – considered armed resistance. But both because it seemed that such action would end in defeat and because – as social democrats – they were committed to legality, they chose to challenge the constitutional validity of the decree before the court set up by the Weimar Constitution to resolve constitutional disputes between the federal government and the Länder.

Schmitt argued the case before the court on behalf of the federal government. Among those on the other side was Hermann Heller (1891-1933), a Jewish socialist legal theorist and public lawyer. The case had been framed by a debate starting in 1929 between Schmitt and Hans Kelsen (1881-1973), also of Jewish origin and the leading legal philosopher of the previous century, about which institution should be the ‘guardian of the constitution’.

The court gave the stamp of legality to an executive seizure of power that laid the foundation for Hitler

The court’s decision is aptly described in Iron Kingdom (2007) by the historian Christopher Clark as ‘mealy-mouthed’. It rejected Schmitt’s argument that, first, it had no jurisdiction in such a charged political matter, and, second, that if it did have jurisdiction, it had no authority to second-guess the executive as to whether a state of emergency existed and as to the appropriate response to the state. But it also rejected Prussia’s argument, first, that there was no basis for the decree, which was as a result invalid; and second that, if valid, ousting the Prussian government was unjustified.

The middle ground the court sought was to maintain the Prussian government in its place as far as its external relations with federal institutions were concerned, while giving control of the internal affairs of Prussia to Papen until such time as order was restored. That the court preserved Prussia’s place in the federal structure was a blow to Papen and Schmitt. But the gift of its internal machinery of government to Papen was a significant victory, which is why Michael Stolleis, Germany’s leading legal historian, calls the decision a ‘milestone in the constitutional history of the downfall of the Republic’. That the court gave the stamp of legality to an executive seizure of power in 1932 by the aristocratic Right in Germany laid the foundation for Hitler’s more dramatic seizure of power the following year and for the claim that the Enabling Act of 1933, by which a thoroughly intimidated Reichstag handed him supreme and unlimited legislative power, was perfectly legal.

Kelsen, whose career had included drafting Austria’s constitution, designing the world’s first dedicated constitutional court, and sitting as a judge on its first bench, accused Schmitt in their debate of presenting a political argument camouflaged as legal. He charged that Schmitt had tried to bring the theory of the divine right of monarchs into the secular constitution with an eye to radical constitutional change in an ‘apotheosis’ of Article 48. In Kelsen’s view, a jurist should maintain a strict separation between legal argument, which he took to be argument about what enacted law and the written constitution formally required, and political argument about the substance of what ought to be the case. The issue of guardianship of the constitution depended on legal not political criteria, though he suggested it would be inconsistent with the idea of legality if the president had the task of deciding on the legal limits of his power. But, in responding to the judgment, Kelsen suggested that legally speaking there was nothing wrong with it, since Article 48 was ambiguous and the constitution had not clarified the role of the court in such disputes.

Schmitt, in contrast, reacted to the judgment with dismay because the court had not accepted his argument wholesale. However, from the perspective of his general theory of politics, the judgment could well be said to support his claim that, in politically charged situations, courts might have no option but to claim a role as the guardian of the constitution while in substance giving the executive a largely free hand.

Of the three, only Heller offered a path to preserve legality in substance as well as in form. In 1927, he had warned that Kelsen’s theory of law was dangerous because it was committed to a politically vacuous idea of formal legality. He thus sided with Schmitt in his contention that a worthwhile theory of legality must have a political point. But he rejected Schmitt’s own theory because it reduced law to politics in a bid to support making the executive sovereign, thus placing it beyond legal and democratic control.

In Heller’s legal theory, the standards for correct judgment about the content of law are legal as well as political, and these standards must govern legal interpretation. In his interventions before the court, he followed through on this position by arguing that the president’s jurisdiction under Article 48 must be limited by the very constitution that granted that jurisdiction, and so in accordance with the correct legal understanding of the presuppositions of the constitution – the fundamental legal principles that preserve the legal and democratic accountability of the executive to parliament, whose laws are the only authentic expression of the will of ‘the people’.

After the Second World War, Schmitt was prohibited from teaching because of his involvement with the Nazis. But he continued to exert a baleful influence on German public law thought. He had a small but dedicated group of devotees in the US throughout the postwar period. After the terrorist attacks on the US of 11 September 2001, he was ‘discovered’ by political theorists and lawyers, prior to his move into the mainstream media. Meanwhile, Kelsen had been summarily fired from his position at the University of Cologne in 1933, where Schmitt also taught, following the law that required the dismissal of Jews in the civil service. (Schmitt was his only colleague to refuse to sign a letter of protest. He noted in his diary that he could ‘not sign this laughable product of the Faculty’, that ‘it is a miserable society that makes such efforts on behalf of a Jew, whilst cold-bloodedly leaving a thousand decent Germans in conditions of hunger and squalor’, speculated that the dean who asked him to sign was ‘perhaps also a Jew’, and complained that he was the victim of ‘Jewish power’.)

While Kelsen made his way to the US, where he taught for many years in obscurity, Heller died in 1933 in exile in Spain of heart disease, a relic of wartime frontline service. Today, Heller’s contribution to legal and political theory is hardly known, even in Germany. But it is in fact most relevant to the debates in our time, particularly in the UK, which – with its centuries-long commitment to parliamentary democracy and the rule of law – might seem the last place where Schmittean logic could make an impact.

For such logic is currently at play in the constitutional debates about Brexit, in which a central figure is John Finnis, emeritus professor of law at the University of Oxford and the major standard-bearer of a deeply conservative, Catholic natural law tradition. Finnis might be the most influential legal scholar of our time. One of his students is the US Supreme Court justice Neil Gorsuch; another, Robert P George – a professor of jurisprudence at Princeton University – was described in The New York Times Magazine in 2009 as the ‘most influential conservative Christian thinker’ in the US.

Finnis’s major impact has been through the aforementioned Judicial Power Project. This project has published a wide range of views, but it is dominated by the agenda of Finnis and his protegé Richard Ekins, also a professor of law at Oxford. They oppose judicial review on the human rights basis required by the UK’s ratification of the European Convention on Human Rights and the subsequent incorporation of the rights through the Human Rights Act (1998). Finnis has argued for what he euphemistically calls a ‘reversal … of the inflow’ of ‘immigrant, non-citizen Muslims’. He opposes the right to same-sex marriage on the basis that ‘homosexual conduct’ is ‘intrinsically shameful, immoral, and indeed depraved or depraving’, while Ekins has objected to the protection of the rights of those affected by the actions of the UK’s armed forces.

The legal arguments in substance placed the UK executive beyond the reach of the rule of law

Judges in the UK have no authority to invalidate statutes and are confined to interpretation of the legal limits on executive action. This has made the Judicial Power Project’s mantra that the judges were undermining parliamentary sovereignty rather unconvincing. It became even more forced when the project’s focus moved to Brexit. Finnis and Ekins argued that parliamentary sovereignty was undermined when parliament sought to control attempts to exit from the EU without parliamentary sanction. On both occasions – first, with Theresa May’s government, and then with Johnson’s – the UK Supreme Court found against the government.

The constitutional issue in these cases was complicated because the government was acting under prerogative, not statutory, powers – powers inherited from a time when the monarch was the political sovereign. The case now known as Miller I asked whether the government could notify the EU of the UK’s intention to withdraw via the foreign relations prerogative. ‘No,’ answered the majority of the court in January 2017 because, on the agreed facts, the withdrawal would definitely change domestic law, and rights and duties under that law, and prerogative doesn’t allow you to do that, at least since 1688. The case known as Miller II asked whether Johnson’s exercise of the prerogative to shut down parliament during Brexit negotiations could be reviewed and, if it could, whether it was lawful. ‘Yes’ it could be reviewed, said a unanimous court in September 2019, and this exercise was unlawful because it had ‘the effect of frustrating or preventing, without reasonable justification, the ability of parliament to carry out its constitutional functions as a legislature and as the body responsible for the supervision of the executive’.

While the issues were novel in both cases, the principles were not. The lawyers for the businesswoman Gina Miller, who brought both cases, were able to build their reasoning on a firm and centuries-old foundation of fundamental legal principles. In this, they followed in the footsteps of Heller. By contrast, Finnis (whose brainchild the prorogation was) and Ekins followed, wittingly or not, in Schmitt’s footsteps by providing the legal arguments, which, while couched as claims about the proper understanding of the separation of powers under the UK constitution, in substance placed the executive beyond the reach of the rule of law.

However, while constitutional principle won the battle, it might well have lost the war. The Judicial Power Project – aptly dubbed ‘the Executive Power Project’ by Thomas Poole, a professor of law at the London School of Economics – is now driving the constitutional policy of the Conservative government. It has vowed to bring about structural legal reforms to the role of the judiciary that will free the executive of legal accountability under the guise of maintaining the sovereignty of parliament.

As Heller and Kelsen pointed out almost 100 years ago, the political stakes in these debates are immense. The terminus of Schmittean logic is not ‘the people’ asserting control of elites, but an elite asserting control in the name of a nationalistic vision, the secular substitute for the divine right of the absolutist monarch. The legal debates of late Weimar shed a troubling light on our situation.