I arrived in Leicester in the late ‘90s as a student, a year after losing my mother to cancer. Having little support, I worked my way through university as a street sweeper, a factory worker, a waiter, a barman, a door-to-door salesman, a cleaner, recycling operative and grill chef. I wanted to be a writer but that seemed like an unattainable dream at the time. A few years later I began working for Leicester’s library service as a literature development worker.

The first initiative I ran was a project to gather the reminiscences of senior citizens. There I was, in my mid-20s, in the meeting room of an older persons’ lunch club. I had a circle of plastic stacking chairs, paper, pens and a dozen volunteers, most of them past their 80th birthday. At the time, I could manage (as I still can) a good line in cocky arrogance. I told everyone how things were going to be and what the project was going to achieve. We were to capture voices from under-represented stakeholders in the local community, thereby encouraging social cohesion. I hadn’t yet learnt that the language of Arts Council England funding bids doesn’t mean much to normal people. Patient smiles greeted my words.

After a long pause, a woman in her 90s started to speak. She had grown up in a children’s home in Leicester, she told us. She had been abused by her father and then by another man at the home. She had worked in factories when she was old enough. Her husband died young, and so did her son. It took her half an hour to say this much. At the end, she said she’d never told anyone about her life before.

I was, in retrospect, unprepared for that project in every possible way. I spent the next fortnight doing a lot of listening and transcribing. The other stories were no easier to hear. Child abuse, abhorred in today’s media, was so prevalent in the industrial communities of England before the Second World War that it had passed almost without comment.

We published a small pamphlet of writing from the project. It seemed puny and easily ignored, but it meant a great deal to the group. There was even a small reception to launch it. A few friends and relatives and a dignitary from the local council came along to enjoy the municipally funded wine and nibbles. The storytellers themselves had all made new friends, and had kept busy instead of sitting idle in care homes. They had had a chance to speak. And a few people had listened.

It would take me the best part of a decade to really understand why that was important.

In dozens of projects and hundreds of workshops, I tried to help people to develop everything from basic literacy to advanced creative writing skills. I worked with teenagers from local schools, who loved vampire novels and wrote their own hip-hop lyrics but said they didn’t like English, until you told them that Mary Shelley was the first goth and ‘rap’ stood for ‘Rhythmic American Poetry’. I worked with groups of factory workers and people caught in mind-numbing call-centre jobs who just wanted to find something, anything, to show that they were worth more than that. I sat in on daylong symposia of Urdu verse and learnt what it is to have Hindu and Muslim communities talk to each other through poetry. I ran projects with drug users and mental health service users, often the same people. A lot of these people were young men, my own age, from roughly the same background as me. I started to see how real the gaps in society are, and how easy they are to fall through.

Any act that helps to empower a person creatively can ignite the imaginative spark without which life of any kind struggles

This all happened in a midlands city of 330,000 people. Leicester now has the third-largest Hindu community in England and Wales, as well as substantial Muslim, Black African, Somali, Polish and Chinese populations. In the late 1800s it was an industrial powerhouse, the hosiery capital of Europe. By the start of the 20th century, it was home to some of the poorest wards in Britain. Throughout the industrial revolution, it had sucked in thousands of rural labourers to man its factories. When the factories closed, that population, lacking any history of education or development, was abandoned, left to subsist on state benefits and lower-than-minimum-wage jobs on huge sink estates. Decades later, many are still there.

I honestly have no idea, beyond individual stories, if the creativity work I did had any real effect. I still get emails from one or two of the school kids I worked with: they’ve gone on to write their own sci-fi books. But there’s a guilt trap in almost any job where the aim is to help other people. Human need is infinite, and you quickly learn the limits of what can be achieved, or else you break from the pressure of attempting the impossible.

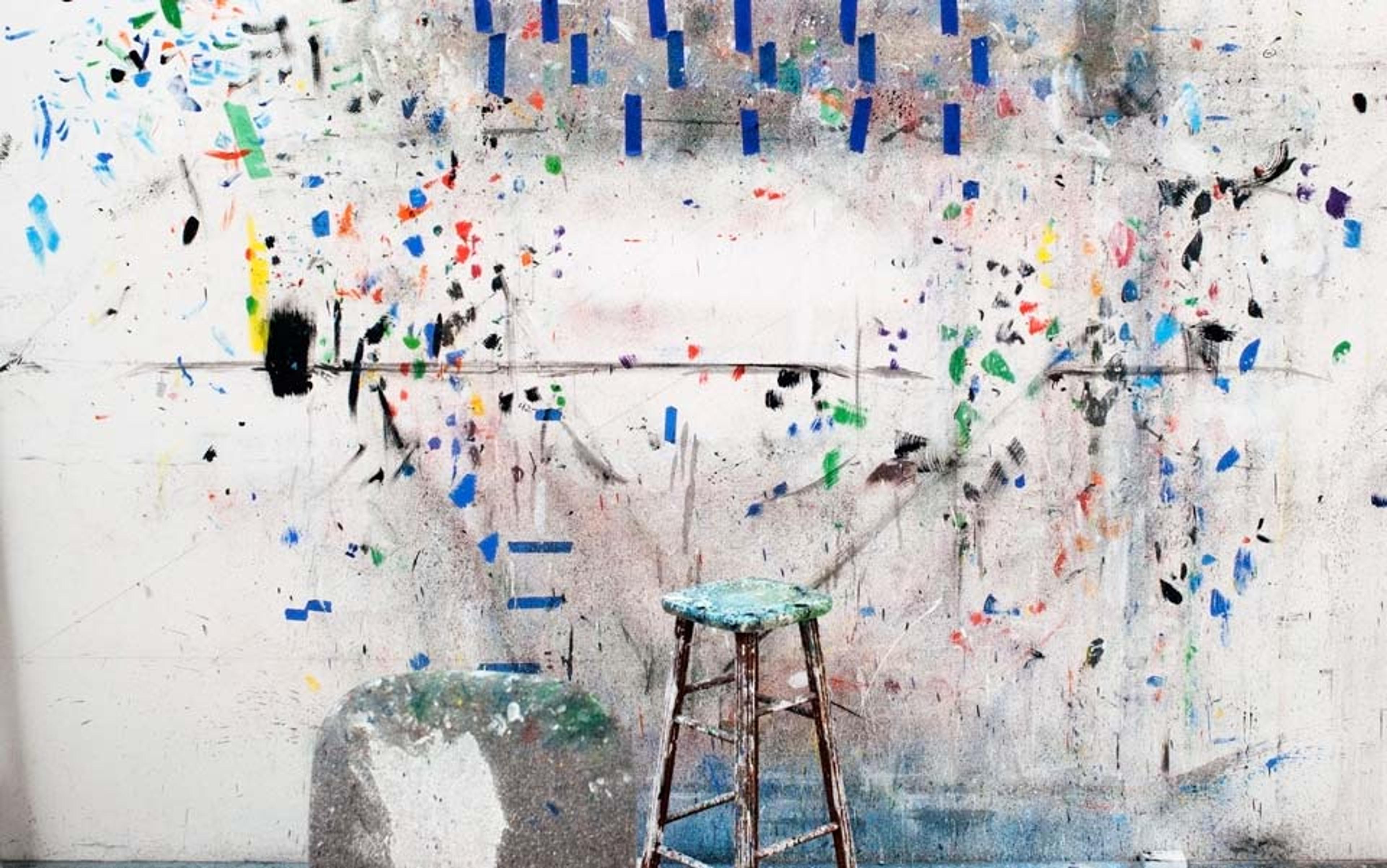

Even so, what I did see again and again was the real difference that a sliver of creative life can make, even to people in the worst circumstances. I saw it most often through the discipline of writing, and I think that the written word makes a good route for many people. But any act that helps to empower a person creatively can ignite the imaginative spark without which life of any kind struggles — and in many senses fails even to begin.

Between the years of 1914 and 1930 the psychiatrist and founder of analytical psychology Carl Gustav Jung undertook what he later termed a ‘voluntary confrontation with his unconscious’. Employing certain techniques of active imagination that became part of his theory of human development, Jung incited visions, dreams and other manifestations of his imagination, which he recorded in writing and pictures. For some years, he kept the results of this process secret, though he described them to close friends and family as the most important work of his life. Late in his career, he set about collecting and transcribing these dreams and visions.

The product was the ‘Liber Novus’ or ‘New Book’, now known simply as The Red Book. Despite requests for access from some of the leading thinkers and intellectuals of the 20th century, very few people outside of Jung’s close family were allowed to see it before its eventual publication in 2009. It has since been recognised as one of the great creative acts of the century, a magnificent and visionary illuminated manuscript equal to the works of William Blake.

It is from his work on The Red Book that all of Jung’s theories on archetypes, individuation and the collective unconscious stem. Of course, Jung is far from alone in esteeming human creativity. The creative capacity is central to the developmental psychology of Jean Piaget and the constructivist theory of learning, and creativity is increasingly at the heart of our models of economic growth and development. But Jung provides the most satisfying explanation I know for why the people I worked with got so much out of discovering their own creativity, and why happiness and the freedom to create are so closely linked.

Jung dedicated his life to understanding human growth, and the importance of creativity to that process. It seems fitting that the intense process that led to the The Red Book should also have been integral to Jung’s own personal development. Already well into his adult life, he had yet to make the conceptual breakthroughs that would become the core of his model of human psychology. In quite a literal sense, the process of creating The Red Book was also the process of creating Carl Jung. This simple idea, that creativity is central to our ongoing growth as human beings, opens up a very distinctive understanding of what it means to make something.

Increasingly, the real benefit that money buys is the time, freedom and power to act creatively

Anyone who has performed any significant creative feat, whether writing a novel or founding a business, will acknowledge the element of inner transformation inherent in the act. The person who attends a writing class in her 20s isn’t the same person who completes a great novel in her 50s, and it isn’t only day-to-day life that shapes her in the meantime: the creative process itself will have been at work. The growth that comes from progress through the stages of any artistic discipline provides a backbone for our intellectual and emotional development as human beings. And it is as a framework for growth that our creative endeavours should be judged. Commercial success more often than not follows growth, but it can become a fatal distraction from it, as we see in the trajectories of celebrities who ape creativity to achieve fame but remain stunted as human beings.

This point raises difficult questions about our society. Much about the way we have chosen to organise our lives, often with the goal of maximising material comfort, is bad for creativity. These problems are most pronounced for the bulk of the population who work inside the structures that support the creativity of others: the factories, offices, shops and other parts of the system of consumer capitalism.

If you are a production line worker at a Foxconn factory in China, a retail operative at Walmart or a call-centre assistant at the Next offices in Leicestershire, the chances of finding any measure of creativity in your work are slim. They are sure to be less than those of the graphic designer using the Apple iPad, the billionaire inheritors of the Walmart fortune, or me sitting here typing this essay on my laptop. As much as our social hierarchies are about limiting and controlling access to wealth, they are also about limiting and controlling access to creativity. Increasingly, the real benefit that money buys is the time, freedom and power to act creatively.

And yet, perhaps internal factors are the greatest barrier to creative fulfilment for most people. We are driven creatures. While our lust for status, money, power and sex can be harnessed towards creative ends, it is more likely to block any spark we might have had. Our consumer culture is happy to cater to these drives. We lose decades of our lives chasing money to buy luxury goods and climbing through artificial hierarchies in the workplace. We struggle with the health problems caused by high-calorie, high-fat diets. We become caught in webs of addiction, trying to distract our minds from the emptiness left by our lost creativity. The novelist Don DeLillo wrote that ‘longing on a large scale is what makes history’. Our longings shape our lives and they shape the world around us. But it is our longing to create that is our deepest drive, and the one that makes us the most human. We ignore it at our own cost.

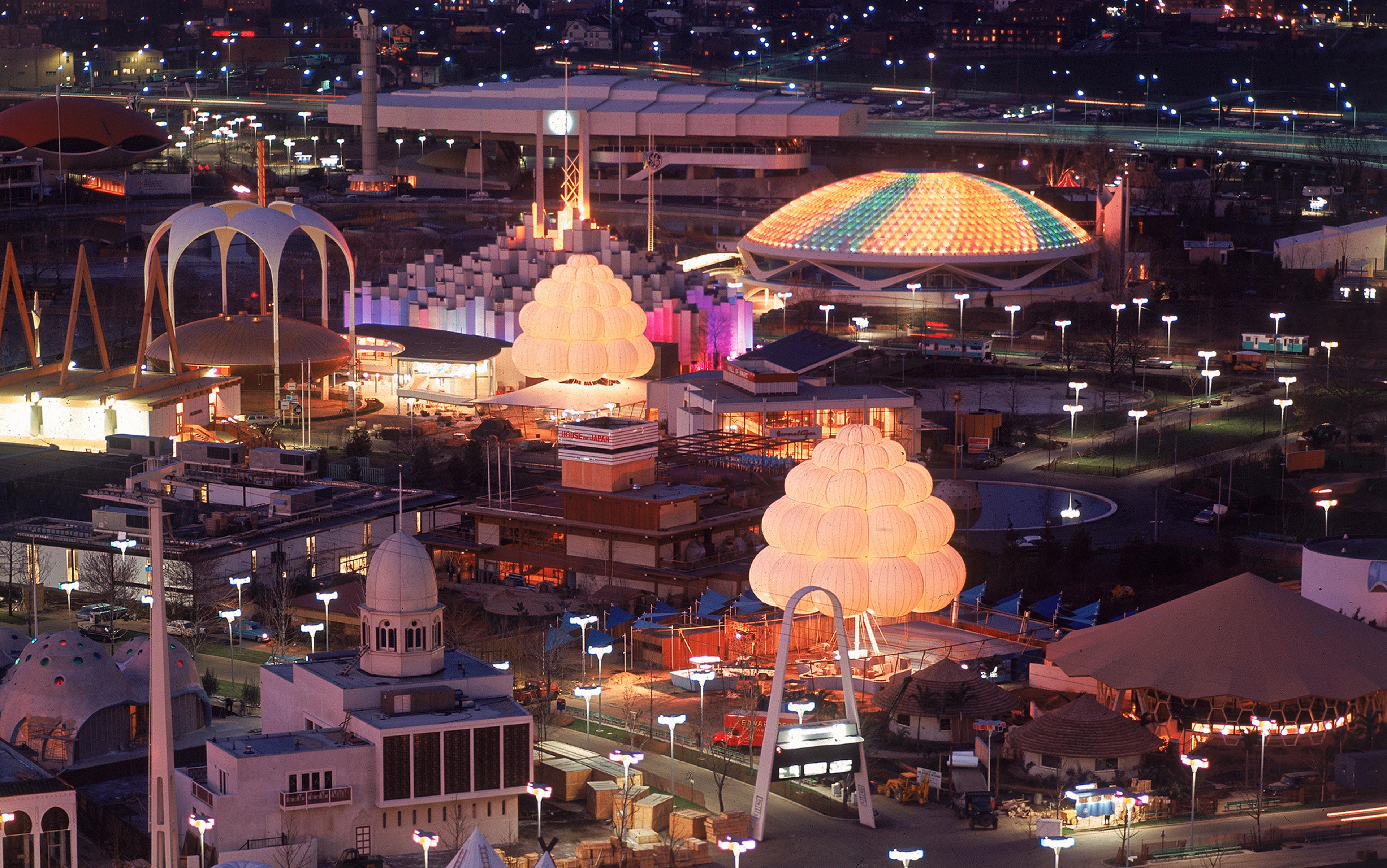

Albert Einstein once said that ‘every child is born a genius’. Educationalists ask: ‘What if every child could be made an Einstein?’ The key to unlocking our full human potential lies in our creative drive. As a writer and critic of science fiction, I am fascinated by the prospect of a world where our full human potential has been realised, and I believe that a ‘creator culture’ is the necessary next step on the path to achieving that vision. We are already well on the way; it might arrive much sooner than many of us expect. Moreover, some of our most pressing societal concerns — from economic decline to environmental collapse — exist because we are resisting the natural evolution of a more creative society.

What might a creator culture look like?

Firstly, it is not a utopia. It is much like the developed world today, with governments, businesses, financial systems, political parties, cities, nations and many other elements of modern, post-industrial life. But it is a society where human creativity has been made the first priority.

The arts and sciences are at the heart of a creator culture, but so are many other kinds of human creativity. Entrepreneurialism, community work, industry; there are many paths. The economic system will have been rebalanced to distribute wealth more fairly to all, permitting the 10-15 hour working week that John Maynard Keynes predicted nearly a century ago. While some people will still be richer than others, wealth will no longer be hoarded by a tiny minority. Poverty as we know it will no longer exist. A more equal society will allow everyone the time and freedom to follow their creative passions, without the paralysing question of whether they produce wealth.

The rise of automation in the workplace will have continued, and the physical work that remains will be distributed more fairly across society. Otherwise, employment in a creator culture will consist almost entirely of knowledge work. The rise of the knowledge worker was among the most remarkable developments of the 20th century, ushering in an era in the developed world that would already seem semi-utopian to the people of the 19th century. For software engineers, graphic designers, data analysts, writers, doctors, lawyers and a huge range of other kinds of worker, the key asset is knowledge rather than any capacity for physical labour. That will be the norm in a creator culture.

Most workers will be freelancers, and to earn a living wage, they will have to work an average of two days a week. Nevertheless, many people will work tirelessly on projects and jobs that relate to their creative interests. Networks will subsume hierarchical organisational structures. As has already happened with open-source software development, many business models will be challenged by networks of knowledge workers providing better products and services at better prices.

In the whole of that universe, humans are the only beings we know with the power of creation

Technology is foundational to a creator culture. The focus of the networked, knowledge-based workforce will be the invention and application of new technologies. The automation of most routine work tasks will provide the base of production that allows such a culture to flourish in the first place. But instead of allowing the wealth created by automation to accumulate in the hands of a few, it must be distributed to the many. We need the right technologies, implemented for the benefit of society; progress can’t be driven by purely commercial imperatives. And to turn the disruptive effects of technology into positive social change we need to think far beyond the currently limited scope of our education system.

Education is the lubricant that allows a creator culture to function. Basic education will often continue into one’s late 20s and early 30s. Most people will return to education many times between spells of employment. There will no longer be an artificial divide between the sciences, humanities and arts: all contribute holistically to a full education. The utilitarian demand for education that only leads to specific jobs will be as frowned upon in a creator culture as behavioural conditioning and corporal punishment are in our own society. The singular aim of education will be human development. Every person should be freed to achieve their full creative potential.

For many people, a creator culture will appear far from utopian. It will demand exceptional levels of independence and self-reliance from its citizens. Creativity, moreover, is always uncertain, always accompanied by the risk of failure. A creator culture will require universal lifelong education, the explicit redistribution of wealth and the deconstruction of many existing hierarchies and authority structures. These will be difficult ideas for political conservatives to accept. But it also will also demand that the structures of government, education and social care that exist to support the bottom of society are continually reformed, and that they ultimately make themselves redundant, as the poverty they serve is eliminated. That, in practice, may be equally difficult for the political left to embrace.

Such a society would also change the shape of certain environmental issues. The climb out of poverty inevitably places demands on the natural resources of our planet. Yet consumerism is built on ever-increasing demand for goods, which fuels economic growth. A creator culture would lead to a plateau in demand and a levelling of growth. The energy we invest in buying consumer goods would instead go towards our creative activities. And though it is very unlikely that our demand for resources will do anything but increase over time, a creator culture might also help us to reach beyond the limits of our own planet.

That’s because, though it isn’t a utopia itself, a creator culture might eventually let us bring about the utopian visions of science fiction. Imagine our planet populated by billions of humans, educated to the standard of the greatest scientists and given the freedom to cultivate their full measure of creativity. At our disposal is any technology we can conceive and create. Within our reach is a universe of unlimited resources. In the whole of that universe, humans are the only beings we know with the power of creation. And there are only a few billion of us — a large number on a small planet perhaps, a vanishingly small one in an infinite cosmos. We’re going to need the wondrous creativity of every single human being to knock this universe in to shape. I wonder, what will we create?

We are Homo Faber, ‘Humankind the Creator’. God did not create us in his image, we created god in our image. We might only be an insignificant species orbiting an insignificant star in an infinite and impassive universe. But we have, perhaps uniquely, the power of creation. Why, then, are we trapped on this ball of rock, repeating the same patterns of self-destructive behaviour, instead of fulfilling our creative potential?

We are caught in a consumer culture that works against our innate creativity. The economic crisis of 2008 might have heralded the collapse of that culture. The consumerist economic model — itself a set of ad hoc compromises following the death of the industrial model — has reached the end of its useful existence. It evolved for a world where technology placed creativity in the hands of the few and television communicated their message to the masses, in what the entrepreneur Seth Godin has called the TV-industrial complex. Today, the internet has decentralised communications, and computers the size of an iPhone place vast creative resources in the hands of broad swathes of the population. The ongoing financial crisis is a symptom of an economy that has fallen behind its own technological capacities.

Notice how many of the new voices that are emerging through social media make creativity their central concern

The instinctive response of our leaders is to reconstruct our consumer culture. The generation holding the reigns of society are trained to think of us as passive consumers. It might take a generational shift before a world leader addresses a speech, not to the world’s consumers, but to its creators.

Yet a creator culture is emerging from the ground up, driven by creators themselves. The crowd-funding platform Kickstarter is only three years old and last year it significantly outfunded the US National Endowment for the Arts. It has allowed artists and entrepreneurs of all kinds to sidestep traditional forms of investment. Crowd-funded creativity is not driven by the commercial imperative of business or the political priorities of government, but by the creative passions of the crowd. ‘Maker’ culture resurrects the spirit of craftsmanship and combines it with technologies, such as 3D printing, that promise to do for manufacturing what the internet did for communication. The principles of ‘open source’ are now being applied far beyond the software development community, invigorating academic and scientific research, politics and government, the media and education. Notice how many of the new voices that are emerging through social media — the cultural curator Maria Popova, an ‘interestingness hunter-gatherer’ who started the Brain Pickings blog; the New York-based Big Think project to sift the ‘best thinking on the planet’; many TED talks — make creativity their central concern. All articulate our new understanding of creativity.

But the green shoots of a creator culture are only just bursting through the rubble of consumerism. Most of us are still plugged in to a mass media that equates creativity with branding and marketing and ignores its potential for human development. Businesses are still afraid of the ideas of their own employees, missing the fact that this creativity is their only hope of adapting to changing times. And our political landscape, dominated by a Left-Right dialogue that only engages with creativity as a source of economic growth, seems incapable of making the changes needed to bring about a creator culture.

In years of working with people struggling to reclaim their creativity, I learnt one very important lesson. Creation is the start, not the end, of the process of growth. We do not escape our tedious jobs, our oppressive social hierarchies, our addictive and self-destructive behaviour, and then become creative. We begin to create; then the process of growth it sets in train helps to free us from the traps that life sets.

We need to learn this lesson as a culture. We have to place the human capacity to create at the very centre of our social and political life. Instead of treating it as a peripheral benefit of economic growth, we need to understand that our wealth only grows at the speed that we can develop our creative capacities. And we must realise that we can no longer afford to empower the creativity of the few at the cost of the many. Our systems of government, business and education must make it their mission to support the creative fulfilment of every human being.