You walk into an art museum. In the first room there is a huge block of chocolate that someone has chewed on. The sign says not to touch it, but out of the corner of your eye you catch another visitor taking a bite. Further on is a pile of wrapped hard candy, surrounded by viewers. Someone else walks over, takes a candy, unwraps it, and pops it into their mouth. People look around uncertainly. The guard seems indifferent. A few gingerly take a candy from the pile before moving on.

Gnaw (1992) by Janine Antoni; 600 lb chocolate cube and 600 lb lard cube gnawed by the artist, 45 heart-shaped packages of chocolate made from chewed chocolate removed from chocolate cube and 150 lipsticks made with pigment, beeswax and chewed lard removed from lard cube; 24 in x 24 in x 24 in each. Installation view from the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles © Janine Antoni. Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York

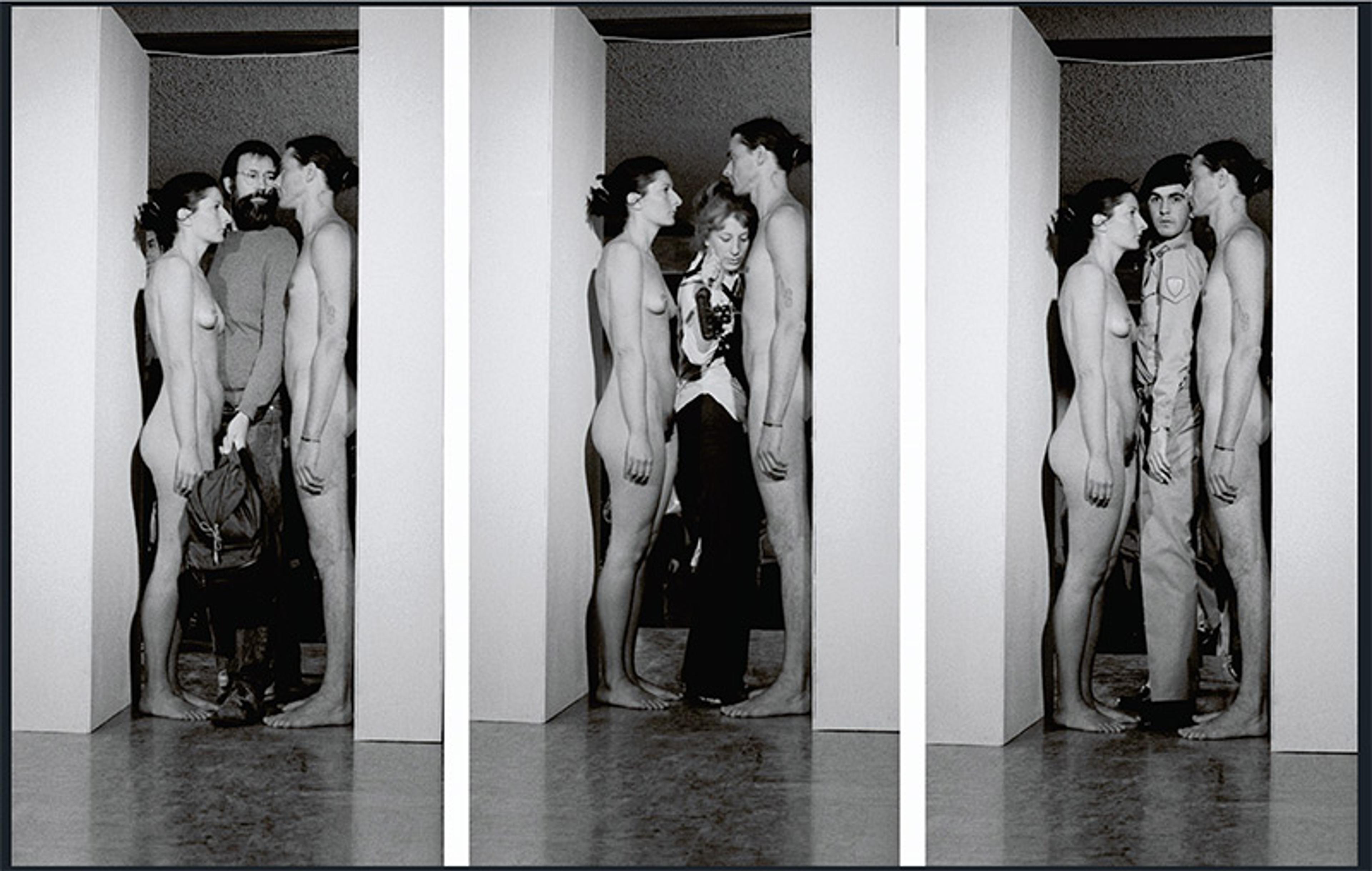

Above the entrance to the next room, a text on the wall says: ‘In order to enter the room, you must hum a tune. Any tune will do.’ A guard stands there watching, listening. Turning to a different doorway, you find another obstacle: two naked people facing each other. The only way to pass through is to turn your body sidewise and squeeze between them. You choose the humming.

Imponderabilia (1977) by Marina Abramović and Ulay, Bologna, Italy. From the series Works with Ulay (1976-88) © the artist. Fair use

In the next room, you encounter a hut made of repurposed garbage, embellished with handwritten notes and a garland of hanging plastic tampon applicators, with two people sitting on the floor inside, having a chat. Should you go in? Or is the chat something you are just meant to observe from the outside?

Finally you see an enormous sculptural wall hanging: several panels made of crushed, metal bottle tops connected with wire, like a chunky tapestry. You’re sure you’ve seen it somewhere before. But it is hung differently this time: new folds have been introduced, some panels are rotated 90 degrees, and the display even turns a corner of the gallery. Is this the same work you saw before? Did someone hang it wrong?

Usually, we know what to do when we go to a museum. Beautiful, finely crafted objects are available to be looked at, and otherwise left alone. We admire the subject matter and the artist’s unique way of representing it. The works afford experiences of visual and intellectual enjoyment. We may return to the same works again and again, finding new elements to enjoy even as the work’s features remain largely unchanged. But this experience prepares us poorly for ‘conceptual’ art, so-called based on the proposition that it features ideas as much as physical stuff.

The history of conceptual art is often traced back to the early 20th-century work of Marcel Duchamp, who presented everyday objects like a snow shovel or a bottle rack as his own artworks, raising questions about the nature of art and proposing that artistic creativity need not involve skilled fabrication. Hard-edged conceptual art, which sometimes involved no material objects at all, had its heyday in the 1960s and ’70s, captured by the artist Sol LeWitt’s statement in 1969 that ‘Ideas alone can be works of art; they are in a chain of development that may eventually find some form. All ideas need not be made physical.’

Bottle Rack (1914; 1959 replica) by Marcel Duchamp. Courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago/Wikipedia

In Advance of the Broken Arm by Marcel Duchamp (1915; 1964 replica of the artwork from the Galleria Schwarz edition). Courtesy Wikipedia

Subsequent decades have seen the proliferation of a movement of conceptual art more broadly construed in which the object, even if sometimes carefully constructed and essential to the work, points beyond itself to an idea or conceptual framework that may not be readily evident. When encountering the works I’ve described – all of which are real – we may experience increasing perplexity. What is going on here? What should we do with these works? What values are they pursuing? Are they any good? Above all, how would we start on getting answers to these questions?

It is not just that we don’t know what the rules are, but that the rules themselves have been withdrawn

The decline of traditional artistic media has helped to pull the rug out from under us. Artists have chipped away at, and sometimes abandoned wholesale, the conventions and boundaries that previously oriented us. Take painting, a medium that was long governed by conventions so obvious that it would have seemed silly to list them: a painting involves paint applied to a surface, presented so that the representational content is the right side up and facing away from the wall, and such that the painted surface is to be preserved for future appreciation. But artists have toyed with this model: Georg Baselitz makes paintings whose content is to be presented upside down; Fiona Banner made a painting whose primary marked surface is displayed facing the wall; Saburo Murakami made paintings whose paint was designed to flake away over time; and Gerald Ferguson made paintings that the purchaser is authorised to repaint if they wish to perform aesthetic ‘maintenance’.

Shy Nude (2007) by Fiona Banner. Courtesy the RISD Museum and © the artist

If the conventions of painting were suspended only for these particular works, it wouldn’t be such a big deal. But, in fact, such manoeuvres have become so pervasive as to destabilise entire art forms. And when the central project associated with the art form is undermined, this makes it more difficult for us to grasp the artist’s own project. Encountering an artwork without a sense of the art form or medium it belongs to is a bit like watching people engage in an activity without knowing whether it is a dance, a sport or unstructured play: we might enjoy watching, or not, but we will struggle to understand what they are doing or why, or offer an assessment that connects to the goals and values internal to the activity. We might be able to infer broad goals just from watching – some participants are trying to transport a ball into a zone, and others are trying to stop them – but the finer significance of their choices will remain opaque. Trying to understand an artist’s choices, when we see only the end product and not the unfolding of responsive activity, is even more difficult.

In fact, the concern about the undermining of art forms runs even deeper. It is not just that we observers don’t know what game is being played or what its rules are, but that the rules themselves have been withdrawn or weakened. There are no longer mandatory goals or structures. It’s as if we have told the team: you can try to transport the ball into the zone… or not. Perhaps you’d like instead to do something up in the bleachers or over at the concession stand, or across town? And, by the way, the ball is optional.

In many years of studying conceptually oriented works, both in the gallery and by way of files held in museums’ back rooms, I began to discern a shared structure that allows us to make sense of the artists’ projects in relation to one another and to their historical precursors. This structure is not readily visible on the surface, since it is not associated with a specific material support. There is an underlying logic and set of constraints that constitute specific choices as meaningful. While the materiality of these works is all over the place, they are bolstered by an immaterial scaffold: a set of rules that point us toward what the artist is up to and what really matters.

When artists make conceptually oriented artworks, they don’t just deliver objects to the museum. (Sometimes there is no persistent object at all.) Display and purchase of these works involves a set of instructions provided by the artist. While delivery of the instructions is sometimes ad hoc, it has increasingly been formalised: many artists prepare a packet of instructions, and museum professionals have developed protocols for artist questionnaires and interviews to ensure the systematic collection of the information needed to display and steward these works.

We are invited to participate in various ways, from contributing a small note or drawing, to coming in for tea

The rules that emerge are usually of three kinds. First are rules for display. These are the rules governing what we encounter when a work is exhibited. To display Félix González-Torres’s ‘Untitled’ (Portrait of Ross in LA) (1991), the museum must acquire a supply of the appropriate wrapped hard candies and display approximately 175 lbs’ worth in a pile on the gallery floor, available for audience members to take. To display Drifting Continents (2009) by El Anatsui, a massive wall-hung work made of liquor bottle tops connected with copper wire, the museum must come into possession of the panels painstakingly fabricated in Anatsui’s studio, but the installers have the latitude to make decisions about how to fold, drape, and orient them to best suit the space and their own taste. To display Jana Sterbak’s Vanitas: Flesh Dress for an Albino Anorectic (1987), the museum must fabricate a new dress out of salted flank steak and allow it to desiccate over the course of the exhibition. Rules for display govern both what to display – specific objects created by the artist, a type of object the artist has designated, or a physical array newly constituted for the occasion – and how to display it: whether in a very specific physical configuration, or in one of a range of ways defined by the artist’s aesthetic sensibility or by some other set of criteria.

_by_Felix_Gonzalez-Torres.jpg?width=3840&quality=75&format=auto)

Untitled (Portrait of Ross in LA) (1991) by Félix González-Torres. Courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago/Wikipedia

The second group are rules for conservation. These have to do with which elements of a work must be preserved for the work to maintain its material integrity. Rules for conservation are important in shaping how the material components of a work will appear to future viewers, but also in identifying which elements are essential to the work’s ongoing existence. When Murakami created abstract paintings whose paint is designed to flake away over time, he embraced within the works a process of change that is normally treated as damage to be prevented and repaired. Whereas paintings have traditionally been intended to have a relatively stable surface and be conserved with the goal of maintaining it, Murakami redeploys painting as an essentially time-based medium.

Finally, we have rules for participation. These specify what, if anything, we as audience members may or must do to experience the work. The works in Jill Sigman’s Hut Project (2009-) are designed not just to be appreciated for their visual aesthetic, but to set up social situations: we are invited to participate in various ways, from contributing a small note or drawing, to coming in for tea. Paul Ramírez Jonas’s The Commons (2011), a monumental sculpture of a riderless horse atop a pedestal, offers a cork surface pierced with thumbtacks as an invitation for viewers to contribute whatever items or messages they like, making the work into a site of collective communication that papers over the object the artist supplied.

The Commons (2011) by Paul Ramírez Jonas. Materials: cork, pushpins, notes contributed by the public. This is an equestrian monument. Unusual in that it has no rider, unusual in that it implies the viewer. It is made of cork instead of bronze because cork is a material that can ‘publish’ an endless number of voices. It opposes the singular voice of the State, or the singular identity of the hero normally portrayed on the horse. The materials and interaction they imply oppose the singular and immutable inscription of the public space that bronze and stone allow. © The artist

These rules set up a certain kind of experience for us: they shape the physical elements we will encounter and how we will be invited to engage with them. They also shape what we will experience over time, if we return to the work: will the physical elements evolve, be replaced, or be preserved? Can the configuration change, or is it fixed? The rules are integral to the artist’s project and to what these works can express, so we need to know about them. While we are sometimes left to figure out the rules on our own through repeated encounters with the work, often these works are accompanied by a short instruction or explanatory text providing key information. If you see Anatsui’s Drifting Continents only once and don’t know that it can be hung differently, you still have a stunning visual array to enjoy: but learning from a wall label or website that the artist allows others to participate in constructing the display allows for a deeper appreciation of the artist’s aims.

The structure of rules allows us to identify where an artist’s project is informed by and diverges from the choices of prior artists. To see this, let’s take a deeper dive into rules for participation. Where a rule for non-participation was once the unstated default, now it is a conscious choice. Sarah Sze fills rooms with meticulous sculptural arrangements made from everyday objects. Her works, while playful, are very much about formal visual effects. In her 1998 book on Sze, the curator Linda Norden observes that Sze’s care in arranging objects, ‘stacking two red, two orange, and one yellow Starburst, and twisting each to just this angle; letting the lamp cord dangle down, not across, the desk – and not any isolated element – determine[s] the larger meanings of the piece.’ Yet the audience does sometimes contribute elements to Sze’s work, despite a rule for non-participation. ‘Some of the things I’ve found,’ Sze notes, ‘are a postage stamp, a mint Life Saver, a bus ticket, a lunch receipt, and a hair band. They’re all things that people probably had in their pocket and spontaneously decided to add.’ These intrusive elements are removed to preserve the work’s integrity.

Of course, Sze could have chosen, like Ramírez Jonas with his cork and thumbtacks, to make works where she provides the initial structure and then welcomes audience contributions. But works involving this rule for participation would be completely different from the works Sze actually makes. Specific formal effects are critical to Sze’s artistic practice, linking her to a long tradition of precise fabrication and visual beauty, even while she incorporates materials like toilet paper, cotton swabs, aspirin tablets, batteries and ladders. Works that invite viewer contributions would quickly spin away from Sze’s aesthetic. This might lead to interesting reflections on forms of play and collaboration, chaos and ruination – the way that all our finely tuned structures are repeatedly appropriated and reappropriated, added to and subtracted from, until they are submerged in the dust of future generations. But this would be entirely different from the expressive content of her actual works, which invite us to revel in visual delight and fascination with materials, their capacities, their evolution over time, and the aesthetic workings of the artist’s mind.

Simply giving us lovely things to look at was not Clark’s project: she invites us to relate to the work creatively

While Sze’s artistic project rules out audience participation, the projects of other artists require it. Lygia Clark’s Bichos (Critters) (1960-66), abstract sculptures made from pieces of sheet metal connected by hinges, were designed to be manipulated by audience members. Often small enough to hold in one’s hands, they can be folded and opened out into different geometric shapes, though they don’t necessarily comply with the user’s wishes. Clark stated that ‘Each Bicho is an organic entity that fully reveals itself within its inner time of expression,’ and our encounter with a Bicho ‘is a body-to-body between two living entities’. People who have played with the Bichos describe a very particular sort of experience:

Clunky and awkward, they refuse to lie flat but don’t really stand up, either.

– Jessica Dawson in The Wall Street Journal, 2014

You push the Bicho one way and it resists, another and a whole part of the sculpture flops over, swinging around with a flap and bang.

– from The Uses of Art (2022) by Sal Randolph

[I]f one does not work with the logic of the beast’s interlocking parts, it will refuse to hold the appropriate shape; indeed, more than this, it will very noisily collapse in a heap, underscoring the participant’s failure to enter into a satisfactory relationship with it.

– from Visualising Feeling (2014) by Susan Best

The opportunity for audiences to engage physically with the works was crucial to Clark’s project and, as the curator Guy Brett wrote in 1994, during her lifetime Clark fought for this opportunity to remain available when collectors and institutions tried to restrict it. Though these works can be painstakingly arranged in static displays to highlight a triumphal, upward-reaching character, simply giving us lovely things to look at was not Clark’s project: she invites us to relate to the work creatively, engage multiple senses, and experience the Bicho as infused with a being that operates in relation to our own – responsive to us but not merely submitting to our will. Exploring the potentiality of these quirky objects, and our own responses of frustration, trepidation, victory and relief, is key to appreciating these works fully.

Whereas physical engagement with Clark’s Bichos is essential for full appreciation, a rule for participation may instead function as a permission, perhaps even reluctantly extended. Romy Owens spent 43 hours installing her work Beauty Is Transformed Over Time, and Not Without Destruction (2020) by driving hundreds of nails very precisely into a gallery wall and connecting them in an elaborate pattern with coloured thread. She then hung scissors nearby with a wall label reading:

This art is not intended to be interactive, but it does present you with a choice. You have permission to choose whether to use the scissors. Leave the string as presented so others can experience the work the same way you have, or cut the string, permanently altering the art, and the experience for everyone else.

Owens has set up an ethically charged situation that engages our thinking about value-laden matters of stewardship and destruction, evolution and preservation, authorial voice and public collaboration, playful participation and prudish withholding, order and disarray.

Opportunities for participation occasionally extend to museum staff but not to the public. With his sculptural wall hangings made of liquor bottle tops, Anatsui adopts a rule for non-participation for audience members but invites installers, whose tastes are typically subordinated to those of the artist, to contribute to the work’s visual aesthetic by choosing how the works will be oriented, folded, and draped. In an interview in 2006, Anatsui describes this as a nomadic aesthetic that he adopts with the aim of ‘giving others the freedom or, better still, the authority to try their hands at forming what the artist has provided as a starting point, a datum.’

If I see this work again, will it look the same? Do I have an option to do something more than look?

Of course, we always have a choice about whether to touch, manipulate or destroy an artwork. Museum files, and occasionally news articles, are full of stories of illicit participation. But a painting by Vincent van Gogh doesn’t come to be about climate activism when soup is thrown on it, and an early 20th-century fresco doesn’t become an essentially time-based work with no fixed appearance when someone ineptly repaints it. These actions are external to the work and what it expresses. On the other hand, when artists incorporate rules for participation within their works, this is part of the artistic project of setting up a kind of experience for us. Choices in this realm have expressive import just like choices about which shapes and colours of paint to apply to a canvas.

The challenge of contemporary art is that, when we see what looks like a static object, or what looks like damage, we no longer have longstanding conventions to guide us in knowing the work’s boundaries and status. A pile of candy, a cube of chocolate, a cork sculpture, an arrangement of everyday objects might – or might not – present possibilities for interaction or evolution. An object that seems damaged may need repair, or the change itself may be something to appreciate. If we see someone else touching or even making off with a physical component of the work, this might be a violation of its structural integrity – perhaps even a crime – or it might point to a possibility open to us as well. Our encounters with contemporary art may thus be infused with uncertainty, which is also a sense of possibility.

The more we know about the diverse projects of contemporary art, the more questions we may have: if I see this work again, will it look the same? Did the artist make these choices, or was someone else involved? Do I have an option to do something more than look? Answering these questions may require that we seek out information, like reading a wall label – a practice some find tedious. But there is something to be said for the value of the questioning itself. Rather than seeing the physical display as a self-contained jewel we are to gaze upon and contemplate, our awareness of its potential to be embedded within various artistic projects allows us to assess how well it serves the project it actually belongs to. If González-Torres didn’t allow us to eat the candy in ‘Untitled’ (Portrait of Ross in LA), the work would have a very different expressive character, not the generosity and celebration of simple pleasures that the actual work offers by way of the opportunity to eat the candy. Awareness of the landscape of rules allows us to contemplate the work in relation to options the artist didn’t pursue, and thereby grasp the import of the artist’s creative choices.

Like every other artistic resource, rules can be used well or poorly: sometimes they set up a situation that is simply boring or tiresome, without leading to any broader reflection. Occasionally, they seem to be expressions of ego or control more than artistic integrity, as when an artist (who shall remain nameless) expressed a post-hoc rule that, in order to display his work, the institution must refabricate the object in a much more costly material than the original. But, at other times, even a simple rule can enliven our perception, embodiment, emotion, cognition and will, leading us to an experience that feels totally fresh, or even to contemplation of broader systems and our place within them.

Back in the gallery, you might feel a bit silly as you walk toward the guard who is listening for your off-key hum, as per the rules of Adrian Piper’s The Humming Room (2012). You notice someone else resisting, irritated at the imposition, while others participate unperturbed, and still others hesitate or turn away. Pulled into reflection by your own discomfort, you might consider how this work reveals the institution’s usual logic through inversion: visitors are required to break the reverent silence of the museum and invited to make a creative contribution to the sensory landscape, regardless of competence or status; the fare to enter is in a currency, the voice, that almost anyone can pay; security guards are asked to protect the integrity of the work not by keeping you away from it but by securing your inclusion. Who benefits from the usual institutional conditions of fees for entry, silence and separation between the audience and the art? How do they enact and maintain broader tendencies of social, economic and carceral control that intimidate some visitors – and artists – or keep them out entirely?

The Humming Room (2012) by Adrian Piper. Voluntary group performance; installation view from Do It 2013 at Manchester Art Gallery, July 2013. Photo Alan Seabright © Adrian Piper Research Archive. Foundation Berlin

Rules are a technology, refined over decades of iteration and development, that allow artists to activate a situation: mobilising change over time in objects, mobilising the institution in uncharacteristic acts of creativity or generosity, mobilising us in decisions about whether to engage in acts of risk-taking (like the project Haircuts by Children (2006-) by Mammalian Diving Reflex), acts of connection (like the performance The Artist Is Present (2010) by Marina Abramović), and even acts of destruction (like the installation Helena & El Pescador (2000) by Marco Evaristti). When they are used well, rules afford powerful, fully engaged experiences of the social and material world and of our own humanity – values that art has always sought, now made available in new ways.