My history with bubble universes began in 1968 when I met Robert Kirshner while we were both undergraduates at Harvard in Massachusetts. He was a lively, funny, interesting fellow. We met up again a few years later, when he was a graduate student at Caltech in California and I was a new postdoc there. At Caltech, he had a piece of good luck that changed the direction of his career and, ultimately, helped reshape modern cosmology.

While he was at Caltech, a bright supernova (an exploding star ending its life) became visible, and Kirshner was able to study it using the huge 200-inch-diameter Hale telescope on Palomar Mountain. Combining his findings with some innovative contemporary methods, he developed a clever way to measure its distance. The distance scale of the Universe was poorly known at the time, and getting more accurate numbers was critical to developing a better understanding of cosmic structure and evolution.

Beginning in the mid-1990s, now as a member of Harvard’s faculty, Kirshner started a group using supernovae to measure the expansion rate of the Universe – a particularly telling indication of how the cosmos is changing over time. Astronomers presumed that the expansion had been slowing down ever since the Big Bang, running down due to the gravitational pull between galaxies. The big question was: how quickly was this cosmic deceleration happening?

To get an answer, Kirshner and his team measured distances to supernovae near and far away, and compared those distances with their velocities of recession. In essence, they were using supernovae as standard lampposts of known intrinsic luminosity, whose distance you could ascertain from their apparent brightness. Then you could look at how much that light had been stretched (shifted toward the red end of the spectrum) by cosmic expansion, and compare the rate of expansion for supernovae of different distances.

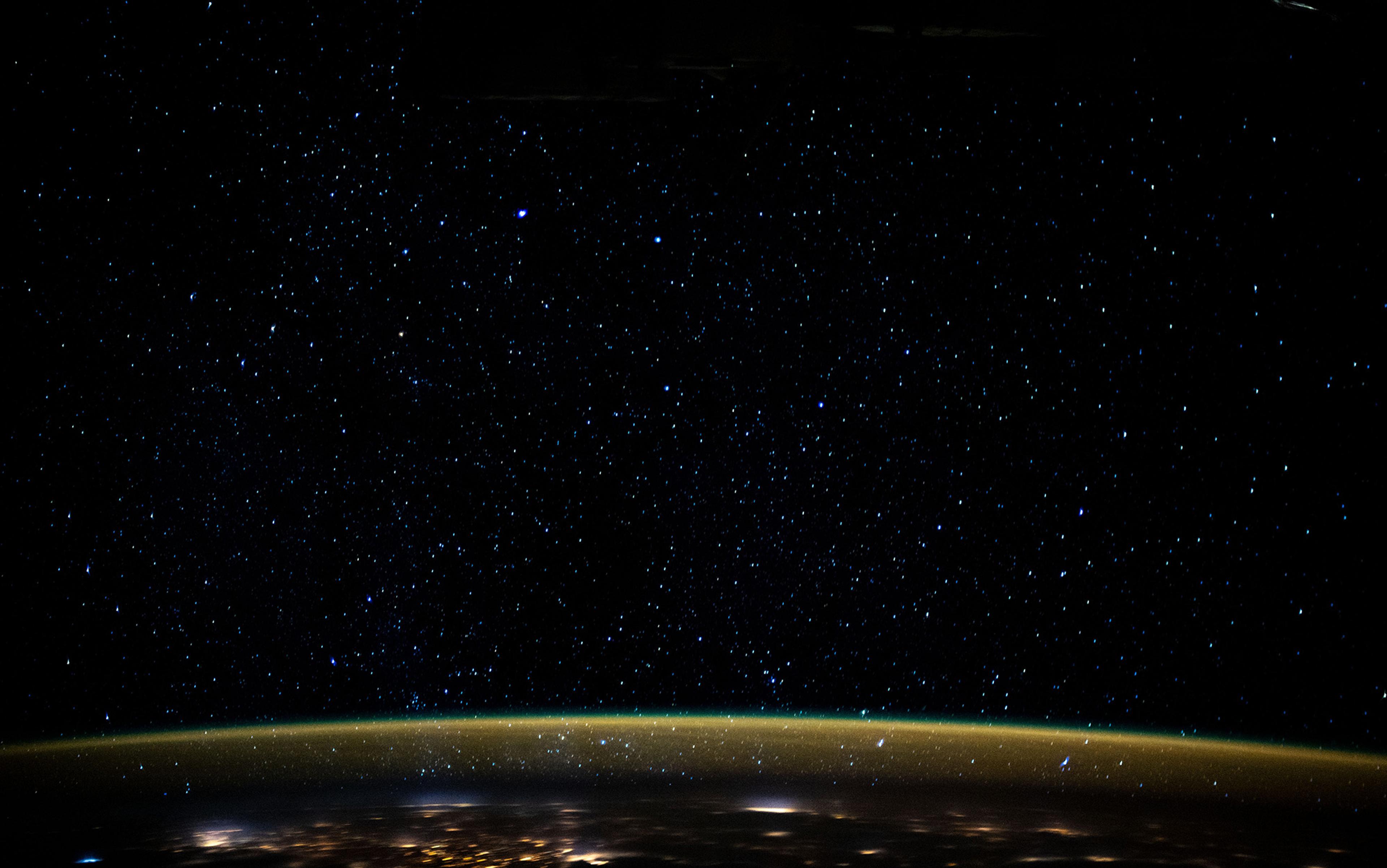

Because of the finite velocity of light, the farther out we look, the farther back in time we see. A light-year, about 10 trillion kilometres, is the distance light can travel in a year. If we look out at a distance of 65 million light-years, we would be seeing a supernova that exploded 65 million years ago, when ancient dinosaurs still roamed the Earth. Kirshner was looking back hundreds of millions or even billions of years. A competing team formed at Berkeley in California to perform the same kinds of measurements, using similar techniques.

Then things got strange. The two groups found that the expansion of the Universe is not slowing down at all, but speeding up! Kirshner’s former students Adam Riess and Brian Schmidt, as well as Saul Perlmutter at Berkeley, shared the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics for this discovery. The supernova data indicated that there was something different and unaccounted for in the make-up of our Universe. Those results also suggested something strange about cosmic geometry: the Universe that we know might be just one of many different cosmic bubbles that could live independently – or that could, under certain conditions, interact and even destroy each other.

The explanation for the accelerating cosmic expansion, surprising as it was at first, was readily available from the theoretical toolbox of physicists. It traced back to an idea from Albert Einstein, called the cosmological constant. Einstein invented it in 1917, as part of a failed attempt to produce a static Universe based on his general theory of relativity. At that time, the data seemed to support such a model. In 1922, the Russian mathematician Alexander Friedmann showed that relativity in its simplest form, without the cosmological constant, seemed to imply an expanding or contracting Universe. When Hubble’s observations showed conclusively that the Universe was expanding, Einstein abandoned the cosmological constant, but the possibility that it existed never went away.

Then the Belgian physicist Georges Lemaître showed that the cosmological constant could be interpreted in a physical way as the vacuum of empty space possessing a finite energy density accompanied by a negative pressure. That idea might sound rather bizarre at first. We are accustomed, after all, to thinking that the vacuum of empty space should have a zero energy density, since it has no matter in it. But suppose empty space had a finite but small energy density – there’s no inherent reason why such a thing could not be possible.

Vacuum energy implies negative pressure because of the theory of relativity (special relativity, in this case, which describes the effects of constant motion). The vacuum of empty space should have no intrinsic preferred standard of rest. The crews of two rocket ships passing each other through empty space should each be able to think of themselves as at rest while seeing the other as moving. The only way that different rocket ships passing each other at different speeds could all measure the same value of vacuum energy density is if the vacuum also possessed a negative pressure of equal magnitude.

7 x 10-30 grammes per cubic cm is a tiny amount of dark energy but has huge effects across the vastness of space

Negative pressure has a repulsive gravitational effect, but at the same time the energy itself has an attractive gravitational effect, since energy is equivalent to mass. (This is the relationship described by E=mc2, another implication of special relativity.) Operating in three directions – left-right, front-back, and up-down – the negative pressure creates repulsive effects three times as potent as the attractive effects of the vacuum energy, making the overall effect repulsive. We call this vacuum energy dark energy, because it produces no light. Dark energy is the widely accepted explanation for why the expansion rate of the Universe is speeding up.

By taking careful measurements of supernovae and other indicators, cosmologists can now plot the expansion rate of the Universe accurately as a function of time and, using Einstein’s equations of general relativity, determine the value of the vacuum energy. The latest measurement is that it is 7 x 10-30 grammes per cubic centimetre. We can also determine the ratio of the pressure to the energy density in dark energy today: -1.008 ± 0.068. (This result is from the Planck satellite team, using a fitting formula developed by my student Zachary Slepian.)

That ratio indicates how dark energy changes over time, and how the Universe changes with it. Within the observational uncertainties, the measured value is equal to -1. If it is exactly -1, then the vacuum energy will remain at its current constant value into the far future; 7 x 10-30 grammes per cubic centimetre is a tiny amount of dark energy but it has huge effects across the vastness of space. It is sufficient to cause the visible Universe to double in size in the future every 12.2 billion years: 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1,024 times its current size, and so on.

As far as we know, this doubling could go on forever. Distant galaxies will flee from us because of the stretching of space between us and them. After a sufficient number of doublings, the space between them and us will be stretching so fast that their light will no longer be able to cross this ever-widening gap to reach us. Distant galaxies will fade from view and we will find ourselves seemingly alone in the visible Universe.

Vacuum energy is not just a recipe for cosmic loneliness. It could also be an agent of change, destruction and rebirth. The value of vacuum energy depends on the values of different fields permeating empty space. One of these is the Higgs field that endows normal particles with mass; that field is associated with the recently discovered Higgs boson. Nima Arkani-Hamed, a physicist at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, has shown that the Higgs field creates a vacuum state that is unstable on a timescale of 10130 years. If the field decays, it could form bubbles of lower-density vacuum state – a different form of empty space, in essence.

10130 years is a very long time. Our Universe is currently only 13.8 billion years old. Still, the theoretical implications are fascinating. The emergence of altered vacuum-energy states is analogous to boiling water on the stove. Bubbles of lower density (steam) form in the liquid, only in this case the liquid is the ever-inflating sea of dark energy. Another big difference: bubbles of lower density vacuum would expand at nearly the speed of light.

An encounter with one of those bubbles would be disruptive, to put it mildly. The value of the Higgs field inside the bubble is different than outside. This means that the masses of the particles in your body would be different inside, too, and therefore the particles in your body would not be able to pass to the inside of the expanding bubble. The bubble wall would hit you and squash you like a bug hit by a car windshield, according to Arkani-Hamed. It would literally be like smashing into a windshield, because light beams are made of massless photons that would not be affected by the change of the Higgs field. They could pass inside the bubble, just as light passes through a glass windshield, whereas the bug does not.

Life would be hard inside the bubble, too. Within these bubbles, vacuum energy is large and negative, with a large positive pressure. Because pressure dominates, there is an overall strong gravitational attraction, which has a crushing effect. Any object like Earth that you might imagine forming inside the bubble would be squashed quickly, due to the big overall gravitational attraction of the negative vacuum energy.

If a bubble formed inside the 28-billion-light-year radius, we would die as surely as that fly on the windshield

These bubbles would form with a minuscule radius of about 10-16 centimetres, smaller than the radius of a proton. Inside would be a negative vacuum energy accompanied by a positive pressure. The bubble wall would therefore see a positive pressure inside and a slight negative pressure outside. The positive pressure would push the bubble wall outward, and the slight negative pressure outside would also pull it outward. As a result, the bubble would blow up like a balloon. Within 10-26 seconds or so, it would accelerate to an outward velocity approaching the speed of light.

At that speed, you would have no warning if a bubble wall were about to hit you. Light signals from the bubble wall would not reach you appreciably sooner than the wall itself. You’d feel it pretty much the same moment that you saw it coming. Fortunately, the accelerating expansion of the Universe offers some protection.

If a bubble were to form more than 28 billion light-years away from us, its bubble wall would never reach us. That’s because the space between us and the bubble is stretching like a rubber band, doubling in size every 12.2 billion years. Special relativity says that you can’t pass another rocket through space at speeds faster than the speed of light, but nothing says that the space itself cannot expand faster than light. For those very distant bubbles, the bubble wall could never cross the ever-widening gap separating you from them. But if a bubble formed inside that 28-billion-light-year radius, its bubble wall would hit us and we would die as surely as that fly on the windshield.

If Arkani-Hamed is correct, the risk of such destruction is very low. Statistically speaking, it’s not likely to happen for another 10130 years, because the rate at which bubbles form is so exceedingly slow. There are more pressing threats to human existence. A vacuum-energy bubble could hit us before next year, but the chances of that are just 1/10130. Put another way, the bubbles are forming so far apart that they do not percolate to fill the space like the froth on the top of a beer. Rather, they are like bubbles in an eternally fizzing, infinitely expanding Champagne bath – if you can imagine such a thing.

Things get especially interesting in the intermediate case: not inside or outside the bubble, but right on its surface. Now imagine you are a massive elementary particle sitting on the outside of the bubble just after it forms. For example, you might be one of the WIMPs (weakly interacting massive particles) we think make up most of the matter holding clusters of galaxies together. Such particles might have masses of order 1,000 times that of a proton. The bubble wall is accelerating outward, pushing you faster and faster. You would feel an acceleration of 1034 times the acceleration you feel sitting on the surface of the Earth, or 1034 Gs. Astronauts can stand only about 10 Gs acceleration in their spaceships. But being an elementary particle, you are tough.

According to Einstein’s equivalence principle, acceleration due to motion (as in a rocket ship firing its engines) and acceleration due to gravity (as on the surface of the Earth) are indistinguishable. You, the hardy WIMP particle, could think you were sitting not on an accelerating glass-like vacuum bubble, but on a massive glass-ball planet with a radius of 10-16 centimetres. If then you were to apply Newton’s laws, from your acceleration of 1034 Gs and your measured radius of 10-16 centimetres, you would deduce that your glass-bubble planet has a mass of 1.5 million metric tons.

As the bubble wall pushed you outward, closer and closer to the speed of light, your clock would tick slower and slower, lengths along the direction of motion would contract, and your ideas of simultaneity would change. (These are more effects of special relativity.) As you moved closer to the speed of light you’d feel as if the current time was still simultaneous with the time the bubble was created. Also, because of length contraction, you’d think you were no further from the centre of the bubble than when you started.

Strange as it sounds, you would not experience the expanding bubble at all. You could think the bubble was static, and that you were sitting on a massive glass planet of fixed radius.

You might be curious and try to run some experiments. If you sent a light beam outward, it would escape to infinity, because it would still outrun the expanding bubble wall. But if you sent a light beam horizontal to the surface of the glass planet, you’d see it skim along the surface as if it were orbiting; the expanding bubble would keep up with the beam as it moves outward. If you threw a ball upward from the surface at less than the velocity of light, you’d eventually catch up with it as the bubble wall continues accelerating outward. Sitting on the bubble surface, this would look to you like tossing up a ball on the surface of Earth and catching it as it fell back down under the planet’s gravity.

As the bubble expands forever, the volume of this universe would increase without limit

This scenario describes what would happen under the laws of physics as we understand them today. But Arkani-Hamed thinks that there might be additional effects in play at extremely high energies, far beyond anything that physicists can probe using the Large Hadron Collider, which discovered the Higgs particle. If so, we might be safe from a bubble disaster for much longer than even the previous calculation indicated. According to the cosmologist Andrei Linde at Stanford University, we might see bubbles forming inside our visible Universe only after 10 (raised to the power 1034) years. That’s a 1 followed by 1034 zeros, a number far too large to write out.

The additional high-energy physics effects would also change the conditions inside the bubbles, in a rather intriguing way. In this case, we expect the vacuum energy inside the bubbles to be less than the current vacuum energy density of 7 x 10-30 grammes per cubic centimetre, but it might be greater than zero. Such a bubble would still expand forever. The positive density inside the bubble would be less than outside, and the negative pressure inside would be less negative than the negative pressure outside, so the more negative pressure outside would still win and pull the bubble wall outward forever. The wall would again quickly accelerate to nearly the velocity of light.

But inside the bubble, life would no longer be so miserable. The low positive vacuum energy could theoretically decay into particles. The inside of the bubble could become a self-contained bubble universe. As the bubble expands forever, the volume of this universe would increase without limit, and it could theoretically form an endless number of low-energy ‘galaxies’ or other objects inside. Suddenly, the bubble starts to sound less like exotic theoretical speculation, and more like the kind of physical reality that we know.

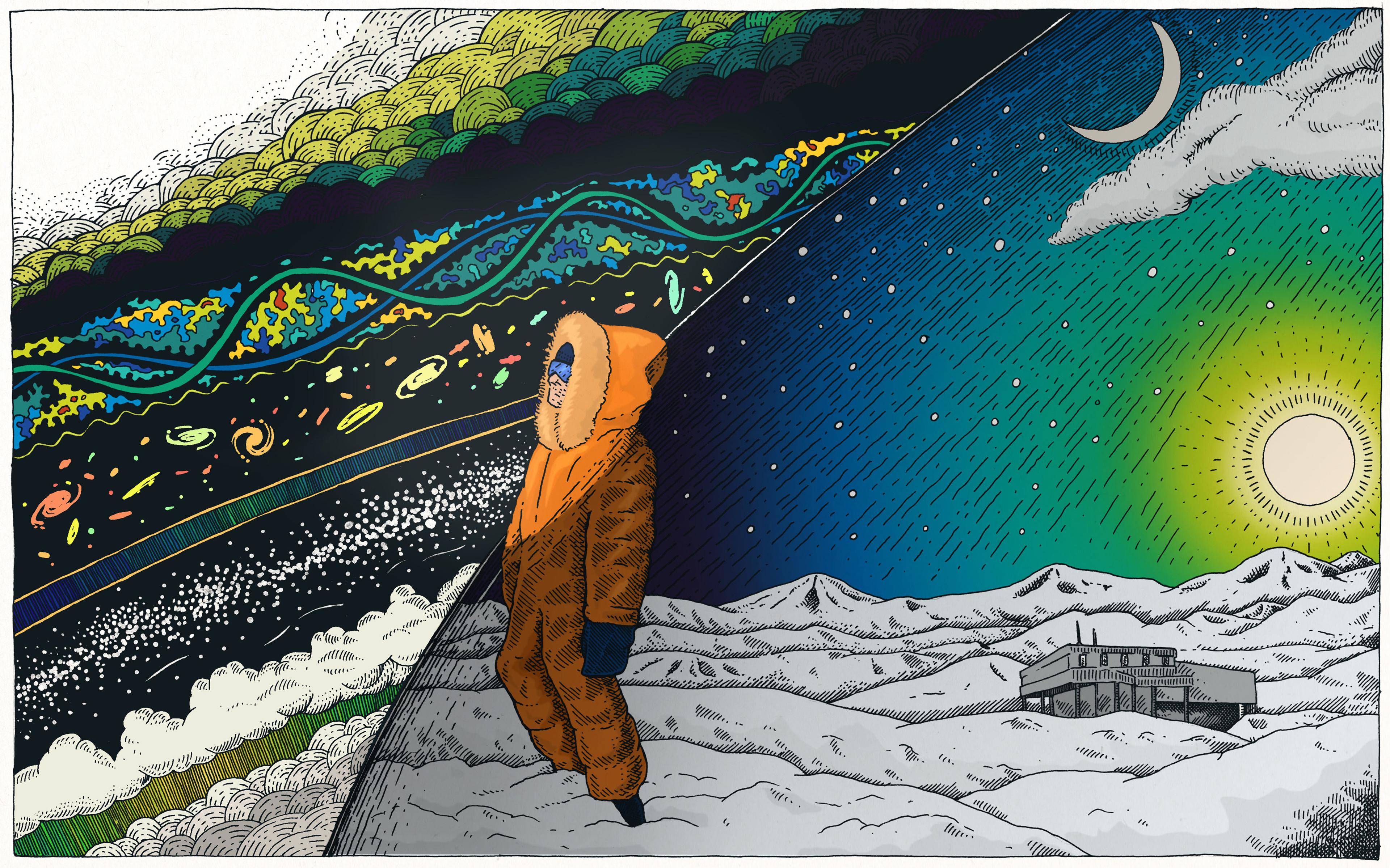

In 1981, the physicist Alan Guth at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology developed a theory of inflation which proposed that, when our Universe first formed, there was a brief period of very high vacuum energy and very high negative vacuum pressure. During that early stage, the Universe inflated very rapidly, doubling in size perhaps every 3 x 10-38 seconds. The theory of inflation solved many major mysteries in cosmology, but came with some problems of its own. Sidney Coleman at Harvard University showed that such a vacuum state would decay by forming bubbles, much like the ones we have been discussing here. An inflating sea of low-density bubbles is highly non-uniform, whereas we can observe that the real Universe is smooth overall.

A year later, I proposed a solution: perhaps our Universe is simply one of the expanding bubbles. From inside one of the bubbles the Universe would appear uniform, because we would be seeing only our own bubble and the uniform inflating sea that preceded it. Building on this idea, I proposed that our Universe was just one of myriad bubble universes forming and expanding in a high-density inflating sea. This universe of universes is now called a multiverse.

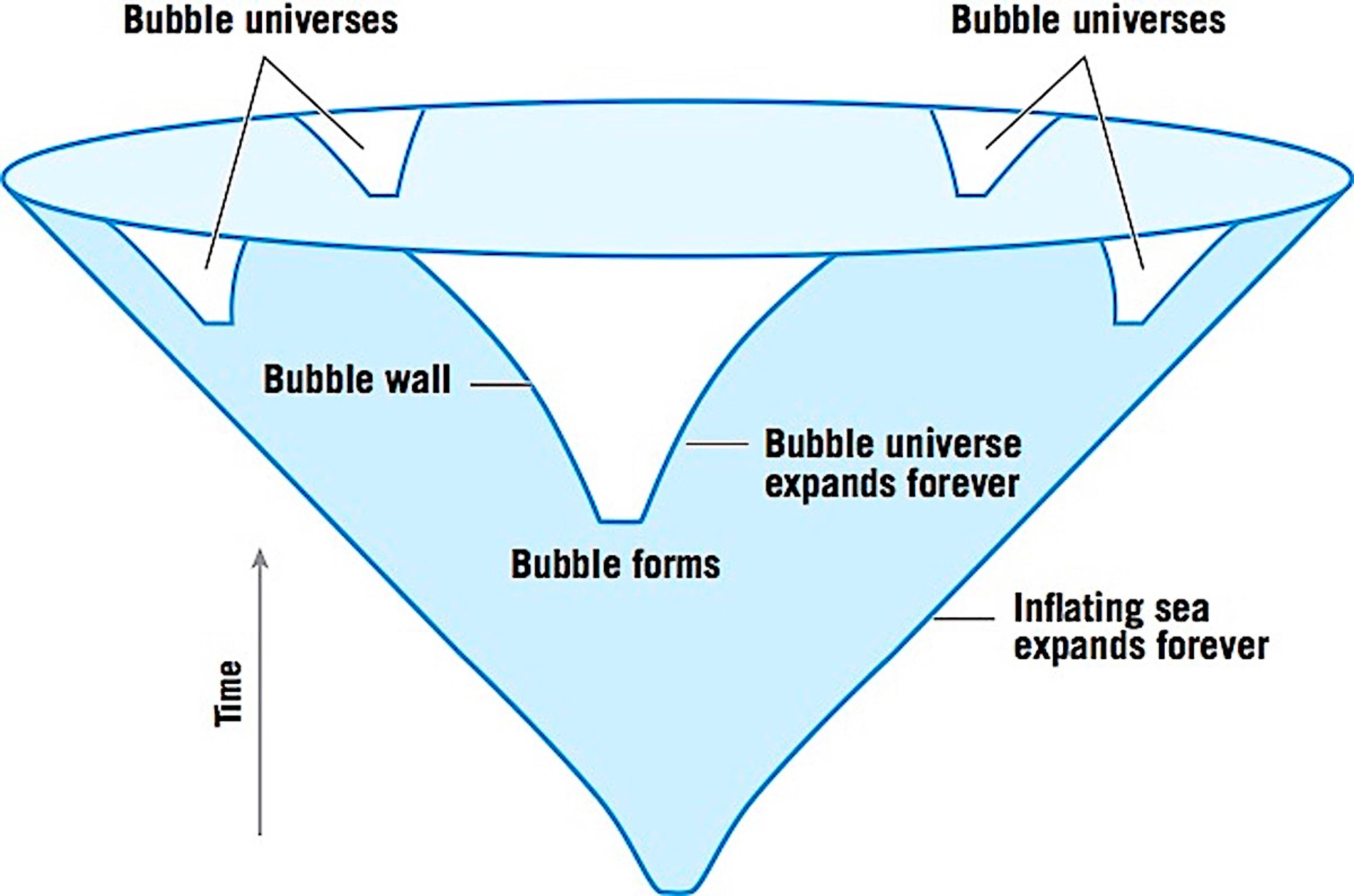

Diagram illustrating the proposed formation of bubble universes. Courtesy the author.

(Although no real observer could view the emergence of all these bubble universes, it is easy to depict the theory behind this process. In the above cartoon, the dimension of time runs vertically, with the future toward the top; one dimension of space extends horizontally, circling the circumference of the funnel. Space expands as one goes upward toward the future. Multiple bubble universes form in an inflating ‘sea’ of space, and each expands forever. Our own expanding Universe is just one of the bubbles.)

Within a short time, independent papers appeared by Linde and by two other physicists, Andreas Albrecht, now of the University of California at Davis, and Paul Steinhardt of Princeton University. They proposed detailed particle physics scenarios that would allow such a bubble multiverse to emerge. This proposal, which became known as new inflation, solved Guth’s problem.

Inflation should go on forever, creating a multiverse that will continue to spawn bubble universes eternally

Later that same year (1982), Stephen Hawking at Cambridge University wrote a paper on single-bubble inflation referencing all of our papers. He noted that a rapidly inflating bubble would produce random quantum fluctuations that would then be tremendously stretched into large-scale structures. Then in 1986 I showed (with my colleagues Adrian Melott and Mark Dickinson) that such structures would naturally lead to a sponge-like pattern of galaxy clusters connected by filaments of galaxies. That pattern has since been verified by numerous large-scale cosmic surveys; it is known as the cosmic web.

The theory of inflation in the early Universe explains how the Universe began expanding some 13.8 billion years ago, in the first moments of the Big Bang, and describes, in beautiful detail, the small fluctuations we see in the microwave background radiation left over from the Big Bang. These spectacular successes of inflation lead us to believe that our Universe emerged from a very high-density vacuum state accompanied by a negative pressure of equal magnitude. It seems pretty clear that once you get inflation started, it is hard to stop it. Inflation should go on forever, creating a multiverse that will continue to spawn bubble universes eternally.

Although we can’t see these other bubble universes, we have theoretical reasons to believe that they exist, because inflation seems to imply that our Universe is not a one-time event. But perhaps the best evidence for inflation in the early Universe is the fact that we see a low-grade version of inflation starting in the Universe now: the current accelerated expansion of the Universe.

Here our story comes full circle. Kirshner’s investigation of distant supernovae eventually led to the discovery that the cosmos appears to be accelerating under the influence of vacuum energy. Theoretical explorations of vacuum energy indicated it could create bubble universes. And the modern formulation of inflationary cosmology ties both of these ideas together.

When inflation was first proposed, no one knew whether a positive energy/negative pressure vacuum state could even exist. Now we know that it can. We know, because we are living in it! Maybe we are seeing today, in the accelerating fleeing of distant galaxies all around us, a low-density recapitulation of the physics that produced our own Universe billions of years ago. And maybe we don’t have to speculate about what life is like inside a bubble. It might be the only reality we know.