An astute commentator recently suggested that Isaiah Berlin would be Riga’s greatest political thinker ‒ if not for Judith N Shklar. We are seeing the beginning of a rediscovery of Shklar and her contribution to 20th-century intellectual life, but she remains something of an insider’s reference. Who was she and what did she have to say that is so important? How did this Jewish émigrée girl from Latvia come to be regarded by many legal and political theorists as one of the 20th century’s most important political thinkers?

Shklar is most often cited as a critic of mainstream liberal thought. During the Cold War in particular, liberalism served as an ideological weapon against the totalitarian threat of the former Soviet Union and its satellite states. But Shklar was concerned about the stifling dimensions of this kind of Western intellectual defence mechanism: it served merely to protect the status quo, and was very often a mere fig leaf for the accumulation of material wealth and for other, more problematic aspects of Western culture. It didn’t ignite any critical reflection or assist any self-awareness of how the liberties of Western democracy had arrived at such a perceived high standing. It was also silent about the fact that fascism had developed in countries that had been identified as pillars of Western civilisation.

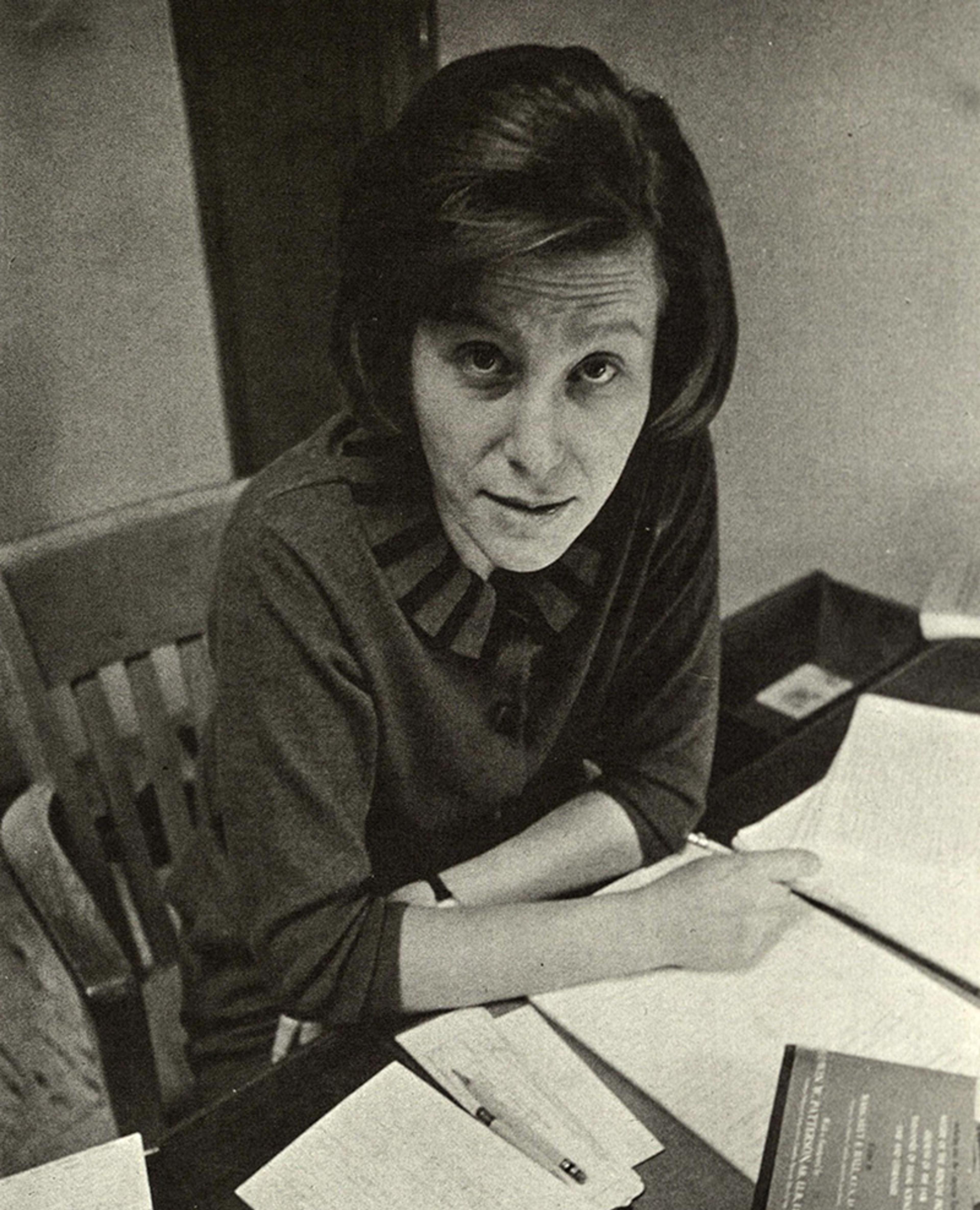

Judith Shklar pictured in the 1966 Harvard Yearbook. Photo courtesy Harvard Yearbook Publications

In contrast to such self-congratulatory rhetoric, Shklar’s criticism aimed primarily at checking the easy optimism of Cold War liberalism, which, despite challenges to its authority, continues to maintain the inflated image of Western democracies. In Shklar’s view, liberalism is neither a state nor a final achievement. She understood, better than most, the fragility of liberal societies, and she wanted to preserve the liberties they made possible. Shklar saw the increasing availability of private consumer choice and the ever-expanding catalogue of rights often propounded in the name of liberalism as threats to the best achievements of Western democracies. In contrast to orthodox liberal arguments that aim at a summum bonum or common good, Shklar advocated a liberalism of fear, which holds in its sights the summum malum ‒ cruelty. Avoiding cruelty, and the suffering it causes, is the chief aim. Other vices such as hypocrisy, snobbery, arrogance, betrayal and misanthropy should be ranked in relation to this first vice.

Both communitarians and some conservative-leaning thinkers have in the 20th century promoted a return to classical republican ideals, based on prescriptive lists of virtues, as a way to maintain or recover good societies. Think of philosophers ranging from Alasdair MacIntyre to Michael Sandel, or of modern defenders of conservative ideas such as Leo Strauss and Roger Scruton. Shklar thought that these efforts were bound to fail. Modern individualism and pluralism had made a consensus on virtues impossible, and there was no turning back. This verdict didn’t preclude her from engaging with some classic republican themes in order to spell out what was wrong with the modern vices she’d identified, but she concluded that there was no agreement about the meaning of these vices. The great exception, she maintained, was cruelty.

Shklar’s book Ordinary Vices (1984) had been largely inspired by Michel de Montaigne and Montesquieu. These two statesmen and political thinkers loomed large for her because they paid due attention to what needs to be avoided at all costs: cruelty, unnecessary suffering, brutal punishment and fear. Both French thinkers, having been experienced political animals, favoured a rather minimalist conception of politics, free from utopian ideals. Their aim and major purpose was to achieve a decent society marked by the absence of fear, not to work toward a political paradise.

Such insight, Shklar argued, provided a form of reasoning and advocated a kind of politics that eventually gave birth to a modern skeptical political tradition. She picked up this fine thread, woven through the history of modern political life, drew it out and articulated it with great clarity and force. The liberalism of fear never became a state, a government or a lasting condition one could simply rely upon. Rather, it was a delicate achievement, always in danger of disappearing or being obliterated by the powers that be. Shklar grasped that the cataclysms of the 20th century made necessary and urgent the promotion of a more skeptical liberalism, one that prioritised avoiding cruelty. As Shklar points out, in light of the extreme experiences of the previous century (and, arguably, those of this one too), ‘liberal democracy becomes more a recipe for survival than a project for the perfectibility of mankind’.

Shklar’s argument has particular bite in a disenchanted world of intractable value conflicts. Her focus on the summum malum and how to avoid it is negatively strong. It is capable of underwriting a universalism of a very particular sort. In other words, Shklar has a theory of the ‘bad’. She wagers that we might be able to know collectively what we want to avoid, without having to agree on a comprehensive life plan or account of the good. This negative universalism works in the service of sustaining political pluralism.

With the liberalism of fear, Shklar had found her own voice. She was portrayed by a number of admirers as an ‘American Montaigne’. This was high praise indeed; but maybe more to the point (and more modest) was Patrick Riley, a former student of Shklar’s, who commended Ordinary Vices for expressing ‘the summa of Shklarism’. She had provided a modern conceptual armoury based on ‘a fusion of psychological confidence and moral skepticism’.

Quite a few critics complained that Shklar’s barebones liberalism was mainly a minimalism or even reductionism. Nothing could be further from the truth, as her consecutive writings and public statements show.

In 1990, at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association in San Francisco, Shklar delivered a highly critical presidential speech, ‘Redeeming American Political Theory’, in which she tried to situate the emergence and history of American political ideas in the context of real power struggles. The main thrust of her address was directed against the often taken-for-granted assumptions of both American exceptionalism and liberalism, and for the relevance of political theory to political science. This was rarely acknowledged at the time but retrospectively it appears that she was a step ahead of other US political theorists in the seriousness of her engagement with American slavery and African-American history.

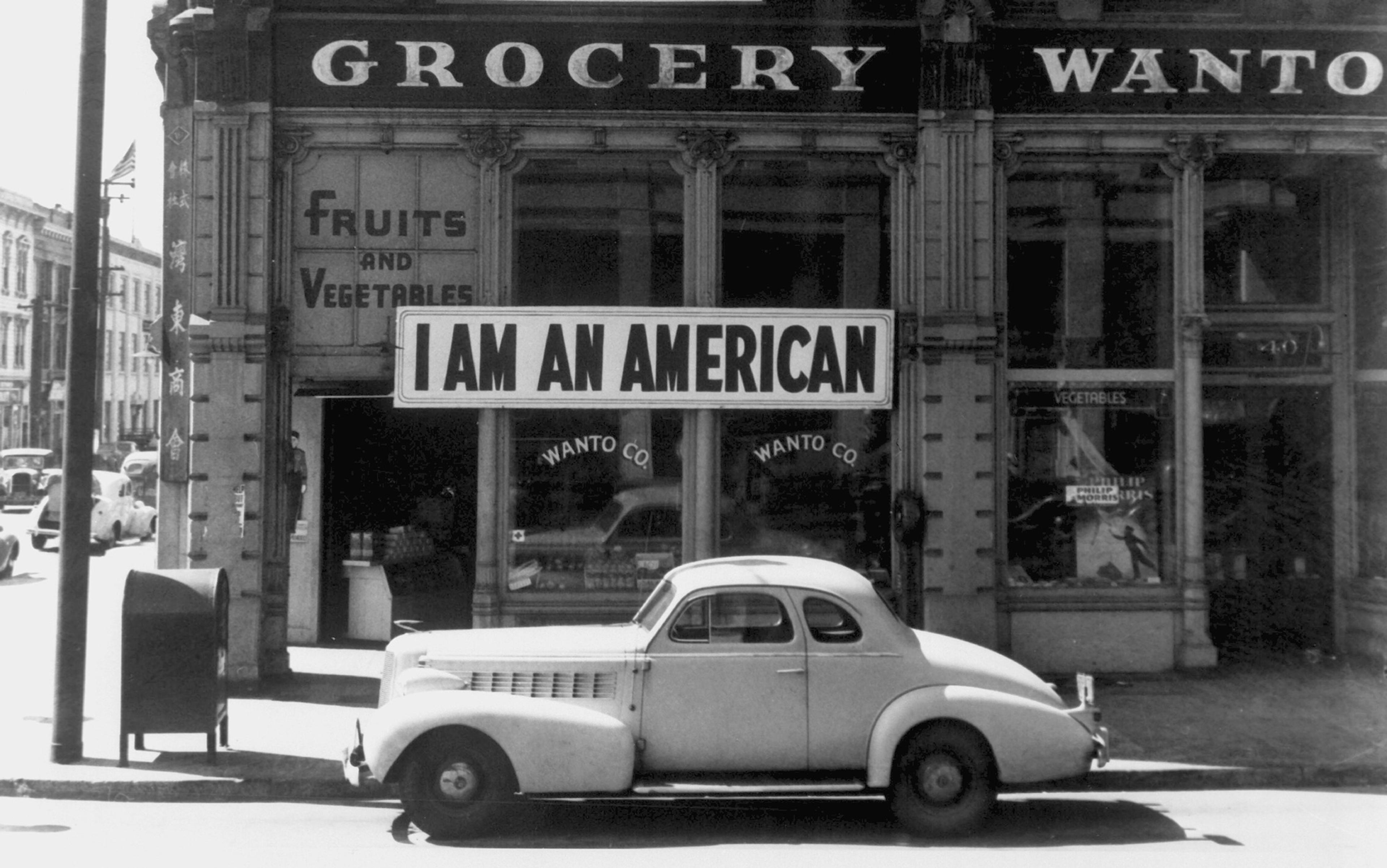

As Shklar demonstrated, the liberal exceptionalism of political science was unable to address and critically engage with the darker side of American history and democracy. After all, for almost a century after the founding of the republic, slavery had remained a legal institution. Other aspects of American history such as the complex struggle for citizenship, the exclusionary politics of American nativism, the often racist motivations of eugenics, McCarthyism, the internment of Japanese-American citizens and so on, had remained anathema or were insufficiently discussed until late into the 20th century.

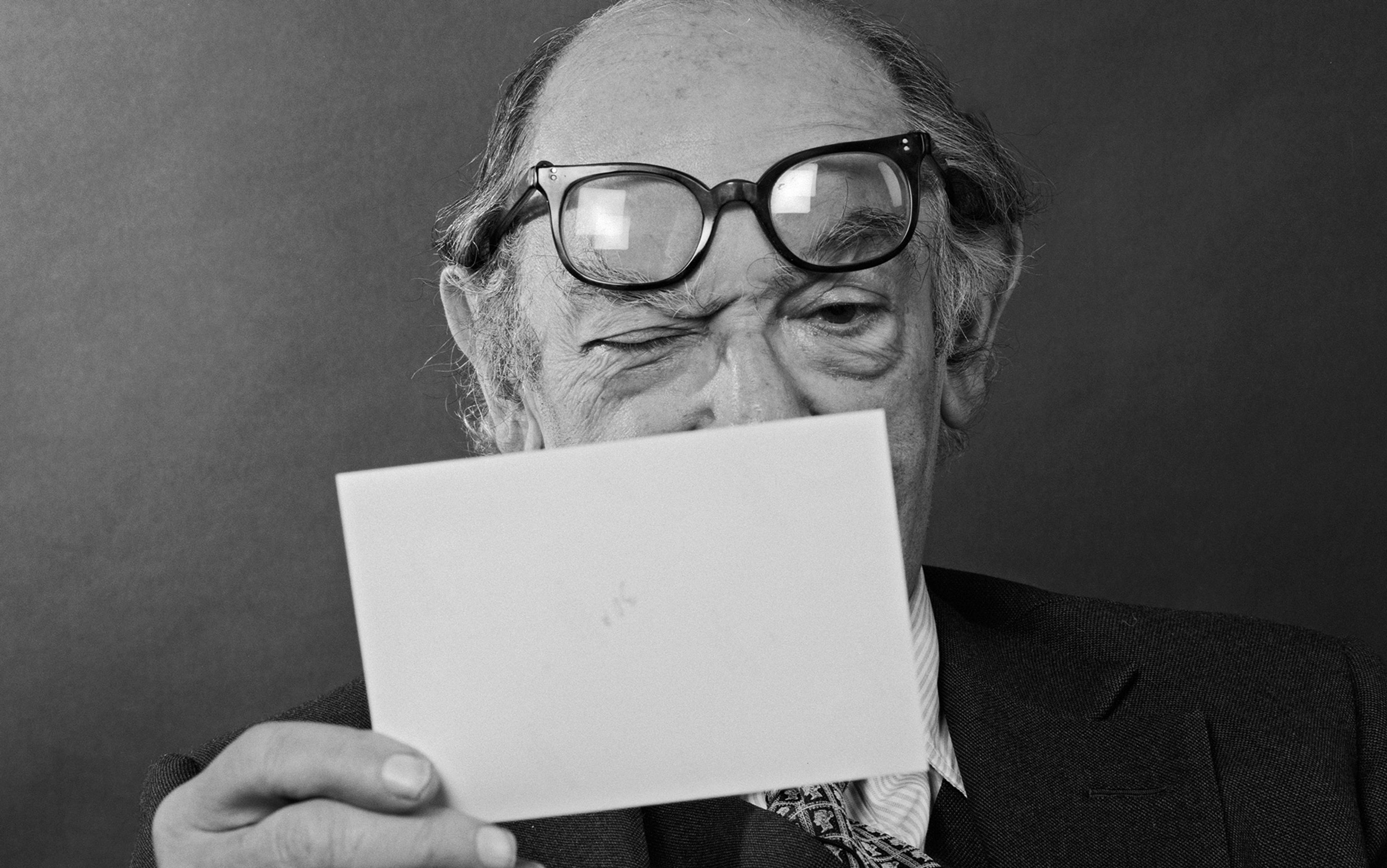

In the same vein, Shklar had earlier criticised Isaiah Berlin and his distinction between ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ liberty. Berlin’s two liberties might have been strong in proposing a liberal position in the context of the Cold War, but they were unable to capture the important peculiarities and lessons of many American struggles. In America, Shklar emphasised, the fight between master and slave had not been just a Hegelian fantasy, it had been real. The fight against slavery was a fight for ‘freedom itself’, it was ‘a way of political life’ and was very differently conceived than the mainly European distinction between positive and negative liberty of which Berlin had been so fond.

Hannah Arendt was another of her targets. Shklar admired Arendt, but felt that something was amiss in her work. Shklar agreed with what Arendt had to say about the unprecedented social and political conditions under which the American republic was first conceived: the notable success the Founding Fathers had in absorbing the revolutionary spirit and energy of the people, establishing the country’s political institutions, and finally the relative success and achievements of the American revolution when compared with the problems associated with the French revolution.

Shklar sees American liberalism as a rather delicate achievement

However, Shklar thought that Arendt’s account of America ‘exploded into wrongness’. Too much of the US and its history was missing from Arendt’s picture. For instance, the US had to fight a Civil War in order to secure the liberal promises of its revolution for African-American men, let alone women. Arendt had no real appreciation of post-Civil War history, the complexities of Southern politics, or of the many dimensions of American race relations, which could not be addressed through a simple distinction between public and private life.

Shklar also differed from Arendt in her understanding of the environment in which Americans found themselves. Using an expression first coined by Ralph Waldo Emerson, she distinguished between the ‘party of hope’ and the ‘party of memory’. The former position was represented by Thomas Paine and Thomas Jefferson, and referred to the rejection of and radical rupture with almost everything that related to European history; Paine and Jefferson not only insisted firmly on living in the present, but their attitudes also allowed them to nurture bright hopes for the future. John Adams, and to some extent James Madison, represented what Shklar called the party of memory: both suggested looking to the past in order to find out what had gone wrong with classical European republicanism.

Adams and Madison shared a more pessimistic outlook than Jefferson and Paine, and Shklar thought this more robust. It allowed her to criticise both Arendt’s classicist republicanism and her uncritical defence of American exceptionalism, and also to give due credit to a skeptical tradition of American political thought. Again, these were echoes of her take on the peculiarly American interpretation of the liberalism of fear. Shklar’s position amounts to one that sees American liberalism as a rather delicate achievement. Unlike Arendt’s treatment of the American political tradition, for which Mount Rushmore’s monumentalism is the obvious symbol, Shklar arrived at a more sophisticated and vital understanding of America and its history – and how its arguments are still played out and matter in our time.

One might ask, where is the positive in all this? Shklar was no system builder, unlike her friend and colleague John Rawls. She was highly critical of Rawls’s attempt to build a theory of justice with his 1971 book of that name. In her own, much shorter book The Faces of Injustice (1990), she suggested a change of perspective: injustice is not just the negative counterpart to justice. Instead, injustice must be studied as a phenomenon in its own right.

She maintained that to give injustice its due demands not only a different perspective but also a different type of narrative, one that helps to identify and recognise the many victims of injustice. Such a new critical approach, she argued, could tell us more about the many faces of injustice than following the false hope of striving for an ever-more perfect state of justice, including the idea of a perpetual amelioration of the laws.

Shklar’s political thought presents particular challenges to triumphalist and exceptionalist narratives. She detected that the legacy of slavery made America’s commitment to democracy often sound hollow. To her, discrimination remained a major scar that had not healed, despite all the rhetoric of equality and hard-fought-for improvements such as citizenship. She clearly sympathised with the civil rights movement and Martin Luther King but also remained skeptical about more radical methods that she thought didn’t contribute to bridging the colour line.

She also rallied against the Machiavellian politics of her Harvard colleagues Henry Kissinger and Zbigniew Brzezinski, and took issue with the ideologised climate of the Cold War and particularly of the Vietnam War. Her position with regard to relations between Israel and Palestine was even more revealing. She never defended the hawks and hardliners in the conflict ‒ and dared to say so in a letter that she circulated to colleagues and friends after a visit to the region in 1987. She reminded her American friends to remain realists, focusing on what could be achieved ‒ and defended. She did so by pointing out that ‘the Jews of Israel have achieved one of the aims of Zionism: they are no different, neither worse nor better, than the rest of mankind. They are neither smarter, nor more virtuous than all the other nations.’

Such an alternative vision could still have made Shklar a hero of the New Left and maybe of the traditional liberal Centre in the early 1970s or even later, but her skepticism made her resistant to becoming a public mouthpiece for a movement or to being turned into a substitute parent. She didn’t shy away from criticising some aspects of the student politics of the late-1960s and early ’70s. She thought them frequently mistaken in their politics of suspicion which often portrayed the US as if it were already a fascist state, and she often found their histrionic happenings and protests over-the-top. She’d escaped Latvia before Nazism and Stalinism arrived, so to her it was obvious that there was a difference: the US, despite its many faults and its sometimes worrying foreign policies (including war efforts such as Vietnam) was clearly not a totalitarian society.

Shklar’s intellectual formation is quintessentially that of an exile. Born Judith Nisse in 1928 into a mainly German-speaking Jewish family, her upbringing in Riga was not that of the typical Jewish shtetl of the region. Her father was a wealthy businessman, her mother a medic. Her education took place in a French lycée, an urban and secularised environment dominated by humanist subjects and language education. In 1939, her parents decided to heed the advice of family friends to escape to Sweden. To add to the trauma, just a few days before leaving Riga, Judith lost her older sister in what seems to have been a tragic accident.

No guardian angel would come to the rescue to guarantee safe passage and asylum

In one lucky move, the family managed to escape the totalitarian threat of both Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia. From Sweden, the Nisse family moved on, equipped with false papers, first through the Soviet Union to Vladivostok, then from Vladivostok to Japan, and finally from Japan via ship to Seattle. On arrival in the US, they were interned but, thanks to a rabbi who had spotted them among mainly Chinese and other internees of Asian origin, soon released.

This odyssey demonstrated to the adolescent Judith that conditions existed in which, independent of how wealthy one’s parents were or how educated one was, no guardian angel would come to the rescue to guarantee safe passage and asylum. It pushed her into a kind of refuge in books and made her sharpen her intellectual interests, in the first instance in classic and modern literature and later in political ideas.

The Nisse family eventually settled in Montreal, where Judith began to study at McGill University, first as an undergraduate and then as a master’s student. Here she met Gerald Shklar, who would become her husband. Equipped with a recommendation from the Rousseau specialist Frederick Watkins, one of the few lecturers to impress Judith at McGill, the freshly married couple moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1951. There Judith, now Judith Nisse Shklar, embarked on a PhD in the Department of Government at Harvard University under the tutelage of Carl Joachim Friedrich.

Shklar took her studies at Harvard seriously and found her interests widening. She and Gerald started a family, and he took on his fair share of caring for their two sons, later joined by a daughter. But it was non-stop, with most days leaving almost no room for anything but family and work.

Soon, a revised version of Shklar’s dissertation was published – After Utopia: The Decline of Political Faith (1957). It was followed by Legalism (1964), a fascinating account of the politics and morality of political trials (almost ignored by legal scholars then but now a standard reference text). A trilogy of books – on Rousseau: Men and Citizens (1969), Hegel: Freedom and Independence (1976), and Montesquieu (1987) – as well as a string of thought-provoking essays, earned her relatively late tenure and, finally, a distinct professorial title – a delayed validation that Shklar shared with many other women of her cohort in higher education, despite their notable output and teaching effort.

It would be facile to draw a straight line between Shklar’s work at Harvard and her experience fleeing Riga followed by a harrowing journey into exile. But it would also be a mistake to maintain that there is no relationship between her early experience and a life spent thinking deeply about the political problems of loyalty, obligation and belonging.

Toward the end of her life, Shklar undertook work on citizenship, exile and emigration to throw new light on the history of political obligation and loyalty. She had always felt that the story of exile sat uncomfortably with the ideal of belonging. As she pointed out in her last two essays and in some of the lectures given just a few months before her death in September 1992 (recently published as On Political Obligation), exile was a fundamental human experience that had captured the attention of historians, poets and novelists. Despite the depth and breadth of interest in exile, political theorists had had little to say on it – something that she attempted to remedy. The exile’s perspective allowed her to address aspects of some core problems of political thought, including conditions for submission to rules and political obligation, but from an original angle. She also reminded readers that exile and critical reflection on the conditions associated with it often engaged the entire personality.

Shklar was aware that today’s emigrants and exiles face conditions different from the ones that she and her family had faced fleeing from mid-20th century Europe. In many instances, there is no host country to offer asylum. There is often no country to escape to. Most of today’s refugees find themselves ‘in pure limbo’, a situation that evokes moral concern, even moral outrage. In turn, those who are outraged and show solidarity find themselves in a solitary situation akin to that faced by Henry David Thoreau: they can neither join a liberating force nor is it always possible to identify fully with the many refugees due to the lack of detailed knowledge, physical distance, culture and lack of shared language. As Shklar rightly observes, there is no ‘we’ here. What exactly do obligation and loyalty refer to? What are the responsibilities of humans to one another in such situations? Since her death, Shklar’s questions on exile have grown weightier, and her insights sharper.

For her, exclusionary practices often give birth to loyalties of dubious quality. One conclusion that offers itself from the modern experience is that cultural and national cohesion remain overrated ideas, prolonging and even causing the conditions in which injustices thrive. Shklar was aware that citizenship might not be the solution to all problems but she was convinced that it remained an essential precondition not only for achieving a democratic and principally open country but first and foremost for making possible the experience of individual liberty.