Anyone serious about their firewood will tell you that they get theirs early in the spring. They will also tell you that the best way to dry your wood is to chop it into short logs and arrange them in loose airy stacks somewhere that the wind can get at them. By weight, dry wood of all kinds releases roughly the same amount of energy when burnt, so the experienced hand knows to look for dry and dense wood and is not easily seduced by volume. I did not know these things until recently, but now that I do, this knowledge seems essential. It makes me a better man.

Most of what I know about firewood comes from a Norwegian book entitled Hel Ved (2011), which roughly translates as ‘solid wood’. It was written by the novelist Lars Mytting and contains detailed discussions of every aspect of sourcing, chopping, drying, storing and burning wood. There are tables in the back listing the drying rates and percentage of ash you can expect from different species of tree. There are references to research conducted by something called the Norwegian Institute of Wood Technology. Mytting is serious about his firewood.

This is the kind of book I knew I had to read before I had even seen a copy. I grew up in Norway, but now live in the UK. Fortunately, my parents could be convinced to send one to me, and I read it from cover to cover the weekend it arrived in the post. I have since studied parts of it as though preparing for an exam.

This is not out of character. The book sits comfortably on my shelf next to a number of other, similar titles. One discusses, in exhaustive detail, the virtues of various flours when baking bread; another contains detailed instructions for constructing a back garden wood-burning oven; another still provides butchery instructions for every bird and mammal found on the British Isles, as well as some found only elsewhere. Collectively, they form a kind of eccentric survivalist reference library that takes up almost an entire Ikea Billy bookshelf.

There are some individuals for whom such a reference library makes undoubted practical sense. If you live in an extremely rural community, some mastery of this knowledge is likely essential both for comfort and survival. I, on the other hand, live in central London. The two pigeons nesting in our chimney suggest that it is a long time since the disabled fireplace in our converted Victorian terrace last saw any action, and the local council would put an end to any aspirations I might have for a wood-burning oven in what can only with considerable generosity be called our back garden. There is, in short, perhaps some absurdity in my taste for survivalist literature.

Mine is an emerging masculine ideal that requires a man to possess knowledge of a particular kind

And yet I am not alone. I belong to a growing community of woodsmen, butchers and craftsmen of various kinds who ply their trade from the armchair. Hel Ved has sold more than 150,000 copies in a country with a population of just under five million, and has spent a year on Norway’s nonfiction bestsellers list. Following its success, Norway’s national broadcaster, which has a public service mandate similar to that of the BBC, aired a 12-hour television programme about firewood; one in five Norwegians watched at least part of it. An international audience also seems to have been captivated, with popular stories following on the BBC and in The New York Times. Evidently the audience for this kind of book extends well beyond the ranks of those to whom it might offer genuine practical value.

A book such as Hel Ved is, in any case, not the portable and durable field-guide that the serious practitioner would require. These are weighty, fully illustrated tomes, designed for a coffee table. They are the reason the height of Billy bookshelves can be adjusted. What’s more, it will come as no surprise that much of this audience of armchair woodsmen are, like me, male. I belong to a demographic of young men who are increasingly hungry for the kind of knowledge these books supply, and who proudly display our survivalist libraries as a mark of status, rather in the way that young aristocrats once displayed their Grand Tour portraits.

In addition to revealing much about firewood and butchery, my growing library therefore suggests something important about contemporary ideas of what it is to be a man. And as a philosopher, I find myself pondering the true nature of those ideas.

‘Hel ved’ means ‘solid wood’, but it is also a Norwegian expression denoting someone of a sound and reliable character. This translation gets much closer to explaining why Mytting’s book and others like it command my attention. They are as much about cultivating a certain kind of character as they are about their particular subject matter. In moments of reflection, I often find myself worrying that a real man knows some things that I do not. He knows how to go out in to the woods and return with usable firewood. He knows how to butcher a pheasant or a squirrel. He knows not just the ideals of nose-to-tail cooking, but the grisly mechanics as well. One reason I might want to know how to butcher a pig or to stack firewood is that I might be required to do so. Another is that I want to be a better man.

Perhaps I am in the grips of the old, outmoded ideal of man as the provider, the hunter-gatherer. This is the vision of manhood embodied in Ernest Hemingway’s solitary heroes, forged through battle with noble adversaries in the deep ocean or on the plains of Africa, or, at the very least, in the bullring. Or perhaps I have been romanced by the same sirens that caught Henry David Thoreau’s ear and drove him away from the city and back to nature at Walden Pond.

The particular ideal I have been preparing for, however, strikes me as both new and different from these predecessors, though each still survives in various forms. In the older cases, the knowledge the man requires plays what philosophers call an instrumental role. Both heroes have independent aims and aspirations, and knowledge is of value only to the extent that it can be enlisted in service of these independent aims.

Many of us have opted instead to perform a kind of alchemy, transforming what was once of instrumental value into knowledge valued for its own sake

The knowledge that I am pursuing, by contrast, appears to be a case of knowledge for its own sake. It will not make me any better at flourishing in my actual environment, or in an environment to which I secretly long to escape. It has almost no practical application in my life, but I desire it nevertheless. Though I do not mean to endorse it over others, or to exclude women, mine is an emerging masculine ideal that simply requires a man to possess knowledge of a particular kind. There are some things a man of this kind simply ought to know. And this new ideal has evolved, I think, fairly naturally from those that came before it.

As a child I was taught how to whittle a bow and arrow from the soft pliable branches of early spring. My grandfather encouraged my cousin and me to make a flagpole from a recently felled tree. He taught us to carry a small knife at all times. I can still gut a fish or shell a crab with ease. These lessons were no doubt imparted because of their presumed instrumental value, and with the hope that they would serve me as they had served my teachers. Yet as the world I live in diverged from theirs, this instrumental value diminished and, in some cases, disappeared entirely. I could have abandoned this knowledge altogether. Not wanting to go this far, many of us have opted instead to perform a kind of alchemy, transforming what was once of instrumental value into knowledge valued for its own sake. But what sort of knowledge are we left with?

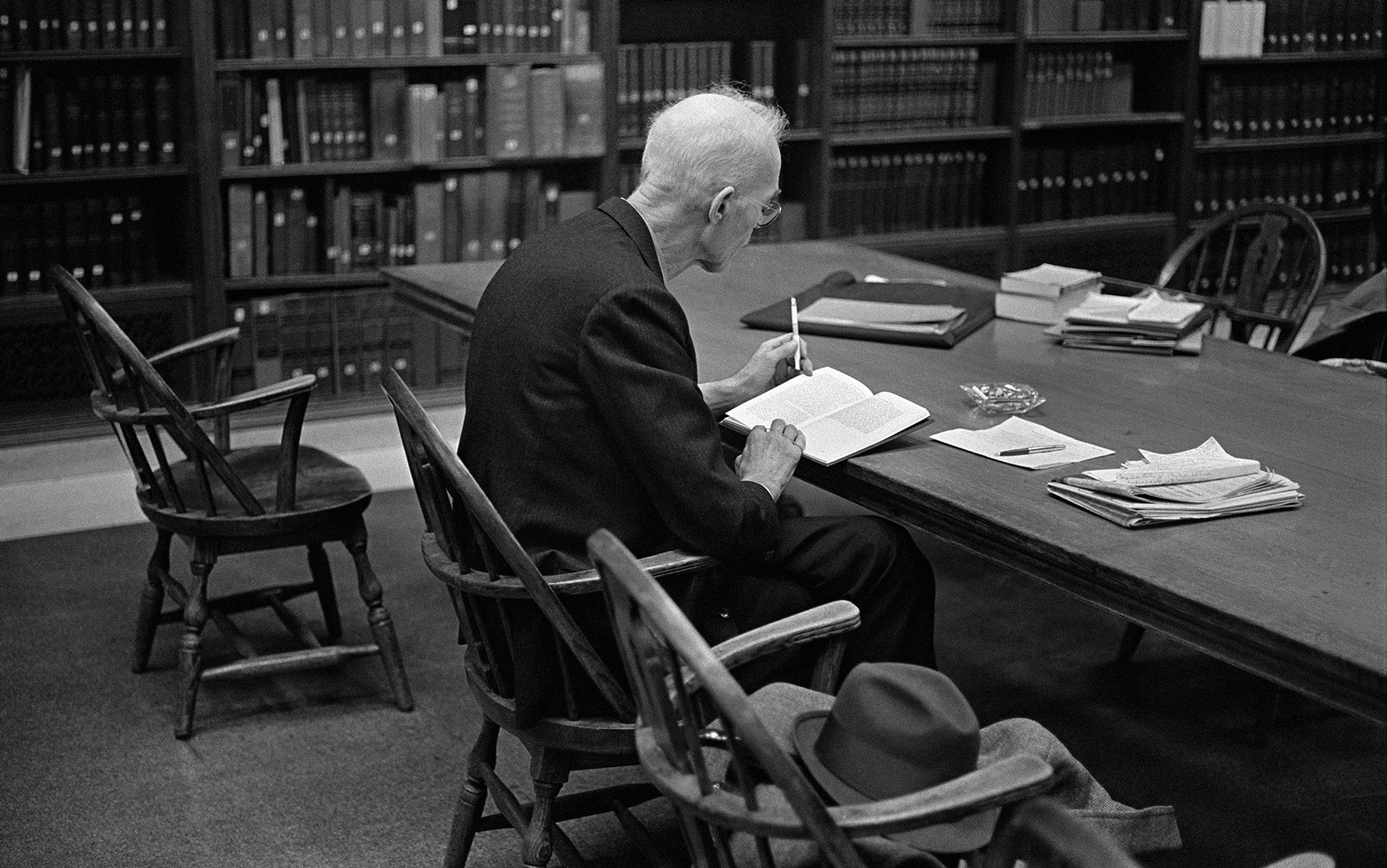

A few months after the end of the Second World War, during which he had served as an intelligence officer, the Oxford philosopher Gilbert Ryle made his Presidential Address to the Aristotelian Society in London. The paper he delivered was one of the first to draw a formal distinction between two different kinds of knowledge. Despite being a philosopher, Ryle appears to have been an eminently practical man. A former colleague of his once told me that his standard example of a good, virtuous activity was digging.

It is perhaps not surprising, then, that Ryle saw himself as correcting an excessive intellectualism, one that he traced at least as far back as Plato’s tripartite division of the soul. In this view, there is a part of us that does the thinking, a part of us that does the doing, and what Ryle considered a mysterious ‘Janus-faced’ intermediary that connects the two, having its foot in both camps but resting in neither.

Ryle found much to dislike about this picture. He noted, for example, that much of what we do — such as chopping wood — can be done intelligently or skilfully, as well as stupidly. According to the Platonic theory which he opposes, any intelligence exhibited in activity must be traced to the part of us that thinks. Doing something, like chopping wood, cannot itself be regarded as an exercise in intelligence. In the Platonic construction, chopping wood intelligently must be to chop wood while simultaneously performing a separate act of thought or theorising in which certain facts are contemplated in a way that guides the activity.

Not all intelligence, or skill, or cunning, is expressed through thought. Some is expressed directly in action

This picture, argued Ryle, is a mistake. The graceful dancer does not do two things at once, but rather one thing in a certain way. The same is true of the woodsman who chops wood intelligently. The intelligence is part of the performance and not separate to it. According to Ryle, intelligence can be exercised directly in certain kinds of practical performances. Not all intelligence, or skill, or cunning, is expressed through thought. Some is expressed directly in action.

The same argument can be made by noticing that thinking and reasoning are themselves things that are done, and that they too can be done both cleverly and foolishly. In ‘What the Tortoise Said to Achilles’ (1895), Lewis Carroll engages his characters in discussion of a simple argument consisting of two premises and a conclusion. The Tortoise challenges Achilles to show him how logic could ever force him to accept the conclusion of an argument. Achilles responds by stating that if the tortoise accepts his two premises, then he must also accept the conclusion. The Tortoise understands, but asks Achilles to make this step in his argument clear by writing it down and adding it as a third premise to his argument. ‘Very well,’ says Achilles, proceeding to restate his argument. If the tortoise accepts these three premises, then he must also accept the conclusion. Again the Tortoise understands, but again he asks Achilles if he should not add this statement as a fourth premise in his argument, since the Tortoise must accept the conclusion only if he accepts this further claim. At this point, Achilles sees that there is no end in sight. He can keep supplying premises indefinitely and the Tortoise can keep asking why.

What went wrong, says Ryle, is that Achilles assumed that knowing how to reason consisted in the knowledge of some proposition that can be written down and placed alongside the other facts of his argument. This, as the Tortoise made plain, is not so. If those who follow Ryle are right, teaching someone how to reason does not consist in teaching some additional fact or premise. There are two kinds of intelligence at issue, each corresponding to the exercise of a different kind of knowledge.

Ryle calls these two different forms of knowledge ‘knowing-that’ and ‘knowing-how’. The former is knowledge of propositions or facts: for example, knowing that the square root of 81 is nine, or that the army of the Ottoman Empire once reached the gates of Vienna. It can be written down and communicated through books, which might be why it comes most naturally to mind when we think of knowledge. Knowing-how, by contrast, is better thought of as a kind of skill or ability. It is the knowledge we exercise when we demonstrate that we know how to reason, or ride a bike, or swim. As the Tortoise purports to make clear, it cannot be reduced to knowledge of the first kind. Knowing how to reason or ride a bike does not consist in a series of facts that can be written down and presented to the Tortoise. It is knowledge of a different kind entirely. This is why, while there are many excellent books about bikes and cycling, there are few books that will teach you how to ride a bike.

If Ryle is right (and there are those who deny it), the relation between knowledge and my masculine ideal is more complex than it first appears. To say that there are some things that a man must know is not yet to say what kind of knowledge they involve, nor yet how that knowledge might best be obtained. If knowledge-that is all that is needed, then Hel Ved and books like it offer a viable route to becoming the kind of man I want to be. If, on the other hand, the knowledge I value takes the form know-how, then there are limits to how successfully I can pursue it from the armchair.

Given the origins of my ideal, it is most likely a combination of the two. Books can lead me part of the way, but they will leave both me and the Tortoise unsatisfied. If I truly aspire to knowing some of the things that were once essential to men like me, I must acknowledge that some of them — some of the knowledge I now value for its own sake — takes the form of know-how. Books will never capture this part of the ideal. Like men before me, I must at some point leave the armchair and head out into the woods. I have read, at least, that early spring is the time to go searching.