‘All the acts of the drama of world history were performed before a chorus of the laughing people.’ From Rabelais and his World (1965) by Mikhail Bakhtin

The central question that anthropologists ask can be stated simply: ‘What does it mean to be human?’ In search of answers, we learn from people around the world – from city-dwellers to those who live by hunting and gathering. Some of us study fossil hominins such as Homo erectus or the Neanderthals; others look at related species, such as apes and monkeys.

Something that sets us apart from these ancestors and primate relatives, and should be of special interest to anthropology, is our unique propensity to laugh. Laughter is a paradox. We all know it’s good for us; we experience it as one of life’s pleasures and a form of emotional release. Yet to be able to laugh, we must somehow cut ourselves off from feelings of love, hate, fear or any other powerful emotion. The fall of a pompous fool slipping on a banana skin is the cliché of comic routines; we laugh at his misfortune because we don’t really care.

A helpful way to get a handle on laughter is to place it in evolutionary context. Other animals play, and their playful antics can prompt vocal sounds. But human laughter remains unique. For one, it is contagious. When a group of us get the giggles, we soon become unmanageable. The evolutionary psychologist Steven Pinker notes that this might be what allowed laughter to be pressed into the service of humour. In How the Mind Works (1997), he writes:

No government has the might to control an entire population … When scattered titters swell into a chorus of hilarity like a nuclear chain reaction, people are acknowledging that they have all noticed the same infirmity in an exalted target. A lone insulter would have risked the reprisals of the target, but a mob of them, unambiguously in cahoots in recognising the target’s foibles, is safe.

Besides contagion, laughter also leaves us peculiarly helpless and vulnerable. We can be doubled up with laughter, or laugh until we weep. Physiologically, it can come close to crying. Nearly every aspect of the body – voice, eyes, skin, heart, breathing, digestion – can be powerfully affected. What we find funny might vary by culture, but people across the world make essentially the same sounds.

When we apply Darwinian theory to laughter, it’s tempting to look for a plausible precursor among our ape-like ancestors. The primatologist Jane Goodall, for example, points out that young chimpanzees often engage in tickling games, making huffing and puffing noises all the while. Maybe, then, human laughter is best viewed as an evolutionary extension of certain playful vocalisations already found among apes.

The objection to this theory is that ape tickle-play vocalisations don’t sound like human laughter at all – they are more like heavy breathing, with inhalations and exhalations equally audible. Another problem is that the apes’ sounds are not socially contagious, and don’t bond the group together in quite the same way. No chimpanzee will laugh just because others are doing so – each animal must itself be tickled.

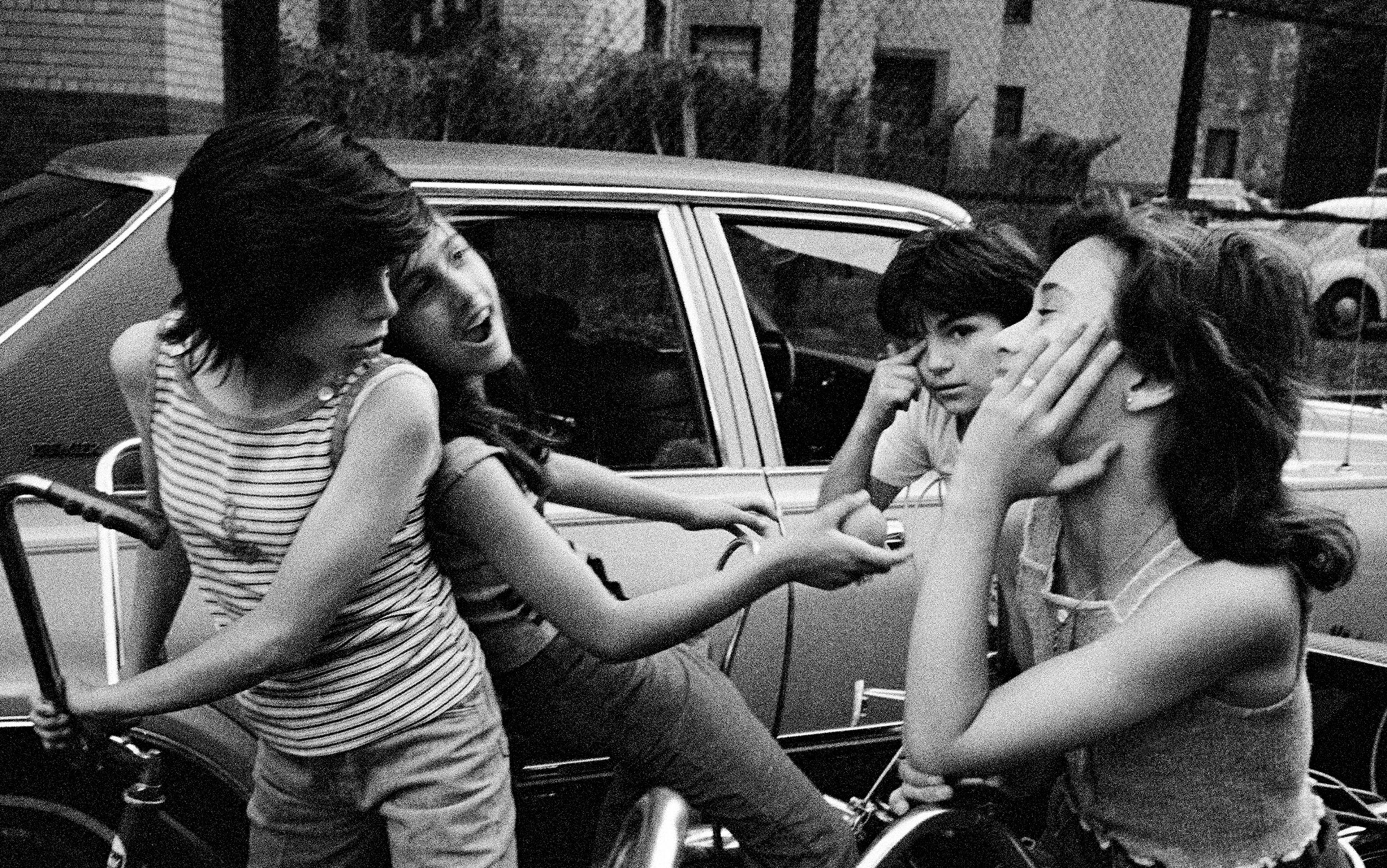

By contrast, when humans meet up on social occasions, the most frequent sounds you’re likely to hear are not grunts and screams but ripples of laughter. Those sounds convey a certain level of relaxed happiness in the company of others. Although monkeys and apes can be friendly, their face-to-face social dynamics are typically competitive and despotic in ways that humans tend to find intolerable. Everyday encounters between nonhuman great apes oscillate between dominance and submission, with facial expressions and instinctive vocalisations to match. There is nothing egalitarian about their encounters.

Building on these insights, scores of theorists have attempted to explain why humans evolved to be the species that laughs. One classic idea is the Superiority Theory, according to which the loudest laughs were originally cries of triumph made at the expense of the enemy. Another is the Relief Theory, in which laughter is thought to have evolved long before words or grammar, as an instinctive way of signalling that danger had passed and everyone could relax. Finally, the Ambivalence Theory holds that laughter erupts as a means of escape from contradictory emotions or perceptions.

What these ideas have in common is their focus on individual psychology. In each case, the thinking is that tension is released with the sudden realisation that there is nothing to fear. For supporters of the Superiority Theory, the initial threat comes from other people who are suddenly exposed as harmless. The Relief Theory agrees that we laugh upon realising we are safe. The Ambivalence theory also proposes that laughter arises when a mental or physical challenge or paradox suddenly dissolves.

The shared insight can be expressed in a single word: reversal. The evolution of the human smile neatly illustrates the idea. When we smile, we stretch out the corners of our mouth and show our teeth. If other animals were to bare their teeth in this way it would be threatening. In the case of nonhuman primates, baring the teeth can be more ambivalent – as in the chimpanzee ‘fear grin’, which simultaneously shows resistance and submission to a more dominant animal. Although humans, too, sometimes behave in this way, we can all spot the difference between a nervous grin and a genuinely warm smile. So it seems likely that the happy smile is probably a fear-grin that has adapted to relaxed social conditions, its significance reversed because there is no longer anything to worry about.

Against existing theories, however, I view laughter as a more profound social and collective endeavour – though still tied to reversal. Smiling, after all, can easily become laughter, so it’s worth exploring whether reversal might explain this behaviour too. When animals collectively mob an enemy, they sometimes bare their teeth and make threatening sounds. Typically, there is something rhythmic, contagious and emotionally bonding about those intimidating screams and cries. The primatologist Frans de Waal describes how an angry coalition of female chimpanzees can sometimes direct a chorus of ‘woaow’ barks at a misbehaving male, maintaining the noise until he finally gets the message. If human laughter evolved through progressive modification of ancestral primate signals, then – as proposed by the late ethologist Irenäus Eibl-Eibesfeldt – similar ‘mobbing’ cries constitute a likely candidate.

Collective laughter might have served as a social levelling device helping to keep everyone in line

Mobbing, then, might be the behavioural precursor to laughter. Taking a step further, it might even help to account for the broader architecture of the human mind. Over evolutionary time, our psychology has been shaped by the demands of face-to-face relationships based on mutual respect; we have adapted to reflect a much more egalitarian socio-political order than anything known among monkeys and apes. The break is so sharp that there must have been some kind of radical regime-change – a human revolution, as I and some of my colleagues call it – to accomplish the transition from ape-like politics to hunter-gatherer-style egalitarianism.

The evolutionary anthropologist Christopher Boehm has proposed an influential theory about the emergence of human society that he terms Reverse Dominance. According to Boehm, great-ape society is like a pyramid, with one despotic leader – the alpha male – at the apex and the rank-and-file underneath.

By contrast, Boehm notes that our hunter-gatherer forebears were profoundly egalitarian. He argues that this was established not simply via incremental change, but in the final stages, through an upheaval so profound that political relationships went into reverse. By this he means that certain rebel coalitions, formed to resist the dominant males, eventually became all-embracing and powerful enough to overthrow the former regime. In its place, a political system was established that still prevails among many hunter-gatherers to this day: Reverse Dominance or community-wide rule from below. What Boehm terms Reverse Dominance is an upturned pyramid, with the rank-and-file dominant over any would-be alpha male.

While Boehm himself doesn’t mention laughter, it seems likely that such a profound political revolution would trigger a great sense of relief. When the threat posed by the fear-inducing alpha-male was defied, we can imagine the rejoicing and laughter that must have accompanied such a reversal of fortune. For our evolving species, perhaps laughter is a marker of our irrevocable departure from the psychology of apes.

From then on, society was decisively egalitarian, with power – now socially accountable – in the hands of the community as a whole. One consequence was that no-one could simply follow their instincts or pursue their own selfish agenda. You needed to take into account what everyone else thought, on pain of being laughed out of town. Collective laughter, then, might have served as a social levelling device helping to keep everyone in line. The outcome was not only a social and political reversal but also a cognitive one: a transition that every child re-enacts as it develops into a self-aware, smiling, laughing, fully human being.

As a consequence of the human revolution, whenever we engage with one another informally, we find it natural to put one another at ease, and to establish at least the appearance of equality. This has become so habitual that our instinctive social signals, inherited from our primate ancestors, have been largely repurposed: the tense primate fear-grin has given way to the relaxed human smile, while the angry mobbing cry has transformed into uproarious laughter. The emotional significance of the signal might be reversed, but remnants of its original form and meaning have been preserved.

For most of the time since the emergence of our species some 300,000 years ago, we have been hunter-gatherers. To answer the anthropologist’s question about what it means to be human, then, modern hunter-gather societies remain particularly important. Every aspect of our minds and bodies has evolved in response to this long-lasting and immensely stable way of life. It’s true that as a species we have evolved to be flexible, a kind of second-order adaptation – but when we find adapting to power inequalities stressful, as many of us do today, it damages both our physical and our mental health. Our need for companionship, for relaxed playfulness, for opportunities to sing and laugh together – all these things have their roots in the hunter-gatherer way of life.

It was once imagined that people in these societies must have always struggled to survive, teetering on the edge of starvation, their relentless quest for food leaving them with no time for leisure or play. It’s hard to know where this strange idea came from, because it is utterly wrong. The prejudice was refuted by the anthropologist Marshall Sahlins in Stone Age Economics (1972), which describes ‘the original affluent society’. Today’s hunting and gathering peoples, Sahlins explained, have a far more healthy and varied diet than people who farm or live in cities. Theirs is an economy of abundance, even super-abundance. Hunter-gatherers typically enjoy hours of leisure time for creative activities such as art, dancing and singing.

A striking feature of these societies is their profound egalitarianism. As an anthropologist, I can report that in any hunter-gatherer camp, equality is maintained by almost nonstop laughter aimed at anyone who is getting above themselves. Everywhere you look, there is a palpable atmosphere of playfulness and fun. It’s no coincidence that the gods of hunter-gatherers are not solemn guardians of morality, but mischievous tricksters whose antics provoke helpless mirth in listener and storyteller alike.

Anthropologists who have studied hunter-gatherers have contrasted ‘immediate return’ societies – those who do not store food supplies – with ‘delayed return’ or storage-based societies. In immediate-return societies, resources such as hunted game are meticulously shared out from the moment the hunters return. No one is allowed to acquire power by storing wealth of any kind. However, once food begins to be stored, certain individuals acquire more power than others, and egalitarianism is progressively undermined.

Today, it’s a settled consensus that Africa is where our species evolved, and where large game animals such as elephants and giraffes have managed to survive into the modern age. For this reason, with few exceptions, African hunter-gatherers have traditionally enjoyed economic abundance and fall into the ‘immediate return’ category. More than city-dwellers or farmers, these people can inform us about how to use laughter as a way of maintaining egalitarianism. Grandmothers and other senior females demonstrate how, by derisively laughing at those who throw their weight around or put on airs and graces, people can be persuaded to respect egalitarian norms.

Nothing in those psychologically individualistic theories about mocking, or about experiencing relief from fear or tension, implies anything specific about the social conditions required for laughter to flourish. But social anthropologists all agree that, among hunter-gatherers, laughter functions as a levelling device, bringing people down to size.

The major figure here is Jerome Lewis at University College London, who has been studying the Mbendjele people in the Republic of Congo for many years. This is a population of immediate-return hunter-gatherers who live in the forests of Central Africa. They are sometimes referred to as ‘Pygmy people’, because of their short stature. Among the Mbendjele, Lewis is able to pin-point exactly how laughter maintains egalitarianism in practice. He explains that it would be risky for a young person to make fun of an older one, no matter how foolish the elder’s behaviour. But senior women exercise a special privilege, seeing it as their enjoyable role to bring down anyone who seems to be getting above themselves.

They might give him a beating with cooking utensils. But their main weapon is derisive laughter

By way of example, Lewis relates how a woman who is upset with her husband’s behaviour – he might be chasing another woman, or not providing enough to eat, or not having sex often enough with her – will go to sit with other women in a prominent place. In loud, exaggerated tones, she talks about her problems with her husband, while her listeners enthusiastically take up her gestures as she mimes his actions and expressions. This is a terrible situation for the hapless husband as he hears the women, children and other men laughing boisterously at his expense.

One of Jerome’s students in the field, Daša Bombjaková, has given us a detailed picture of how women’s laughter manages to keep men in line. In any dispute with a man, a woman can expect support from other women, regardless of the rights and wrongs. Should a male threaten or attempt violence, other women will immediately support the victim and give her shelter and protection. They will collectively insult the man and might give him a beating, typically with their cooking utensils. But their main weapon is derisive laughter.

Male sexual behaviour is the constant butt of jokes. Women have a powerful ritual called Ngoku, designed to re-assert female values. The entire female community comes together to sing and dance, seizing control of the public space and making graphic, ribald fun of male sexuality. It is also during the build-up to Ngoku and immediately afterwards that women will take part in mòádzò – female, public, mocking re-enactments of stereotypically male behaviour. Bombjaková went to the trouble of listing the faults likely to be ridiculed. These included greediness, selfishness, dishonesty, cheating, laziness, arrogance, boastfulness, carelessness, cowardice, intolerance, moodiness, impulsiveness, aggression and possessiveness. A feature of mòádzò is that few words are used. Instead, performers utter expletives and onomatopoeic sounds that are amplified by the audience and stretched out musically.

A senior woman might start the ball rolling by silently imitating some characteristic mannerism of her target. One or two others immediately grasp whom she means. They begin to laugh and, because laughter is so contagious, soon everyone is laughing and uproariously pantomiming the behaviour being mocked. After a while, the only person still not laughing is the man himself. But the laughter goes on until, at last, even he gets the joke. The chorus subsides only as he finally joins in, laughing at his own expense. He now sees the funny side of things, at last viewing himself as others see him. His behaviour was comical because of its incongruity with what is deemed socially acceptable. The culprit might have imagined he could get away with such outrageous actions. But hunter-gatherer women adopt a collective perspective on badly behaved males, and will do everything possible to bring each culprit back into line.

Although it can seem cruel, the truth is that women’s laughter is generous and inclusive. Despite its hurtfulness, the target is invited to save face by joining in. A good mòádzò performance will succeed in calming the atmosphere by allowing everyone to laugh and forget their anger.

Looking at laughter from the perspective of an anthropologist, it’s possible to claim that all humour is essentially political. That insight transcends comedic forms such as satire; my point here is that humour in general, whatever its content, is political by nature. Down to the smallest details of our lives, our relationships and encounters involve exercises and exchanges of power. In the face of these dynamics, laughter is an equalising gesture, a restoration of a rightful order in the face of an unjust hierarchy.

Similarly, when we find something funny, it’s often because of some incongruity between mind and body, the ideal and the real. That division is political to the core. The humour of medieval carnival, according to Bakhtin, relied on the way that the body makes a mockery of the lofty purposes of the mind. Buttocks, thighs, coughs, splutters, farts, ‘the bodily lower stratum’ – all mock the spiritual solemnities of humourless bishops and other supposed guardians of morality. Comedy is about exposing the gap between our supposedly noble intentions, and the grimier truths about our condition. For this reason, the amusing features of life are never far away; if something seems funny, it’s because it’s uncomfortably close to home.

Perhaps this explains why nothing in nature can be truly comical. A strange rock formation or a pattern in the clouds might seem weird or intriguing, but it can’t be amusing; rocks and clouds don’t have human-style intentions and motivations, so they can’t be tripped up. Animals might seem funny, but only because we anthropomorphise them. They can’t really be brought down to earth, because that’s where they are already. For a situation to provoke genuine laughter, it must form a pattern that we recognise from our own mental and social lives.

Laughing, then, appears to be intimately tied to our ability to reflect back on ourselves. When we chuckle at our own foibles, we show that we are no longer trapped inside our individual egos, but can see ourselves through one another’s eyes. Likewise, when speaking, we separate ourselves from those around us by using words such as ‘I’ or ‘me’, drawing attention to ourselves as one person among others, as if from outside. Language would be impossible without the ability to adopt such a reverse-egocentric standpoint.

Humans are instinctive egalitarians, who work best with one another when no one has absolute authority, when teasing is good-natured, when there is sufficient affection and trust for shared tasks to constitute their own reward. Laughter is a vital part of this picture – not simply a psychological relief valve, but a collective guard against despotism. When moved to laugh by those around us, we reveal ourselves to be truly human.