Shortly after Rachel Bespaloff’s suicide in 1949, her friend Jean Wahl published fragments from her final unfinished project. ‘The Instant and Freedom’ condensed themes that occupied the Ukrainian-French philosopher throughout her life: music, rhythm, corporeality, movement and time. One of Bespaloff’s key ideas, ‘the instant’, is less a fragment of duration than a life-changing event, a moment of embodied metamorphosis. In the midst of a noisy world, torn between transience and eternity, the human being listens to the sound of history. Had she completed and published it, ‘The Instant and Freedom’ might have become the masterpiece of an important early existentialist thinker. Instead, her name is hardly mentioned today.

Yet Bespaloff was a brilliant and original thinker, among the first wave of existentialists in France. Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre and Gabriel Marcel all admired her. A professional dancer and choreographer, she had finely tuned ears for the musicality of philosophical writing. For Bespaloff, philosophy is a dynamic, sensual activity of listening to and engaging with the voices of others, including those long dead. In dialogue with Homer, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche and Heidegger, she found her own voice. At the heart of Bespaloff’s world is an original conception of time shaped by embodiment and music: the instant is a silent pause that suspends history’s repetitive rhythm. Through our bodies, we experience that break from history as a brief moment of freedom.

Her more famous contemporary Simone Weil also used her body to express her philosophy: Weil eventually starved herself to death in solidarity with friends and compatriots in occupied France. Bespaloff shared Weil’s interest in attention, listening and waiting as mystical practices of the body. For both thinkers, philosophy was an existential embodiment of their ideas. However, Bespaloff did not use her body as a weapon against itself; rather, she was interested in dance as a creative alchemy of movement. Bespaloff’s philosophy of the body is closely linked to the experience of time: it is our embodied day-to-day existence that measures and gives rhythm to time. In an essay on Homer’s Iliad written during the Second World War, Bespaloff captured the experience of living through the horrors of exile and war. The human being, ‘bound to her time by disorder and misfortune, acquires a new perception of the time of her own existence.’ (All translations here from the French are my own.)

Bespaloff’s own life was one of repeated displacement: she moved from Ukraine to Switzerland, Paris to southern France, to Mount Holyoke via New York. Born in 1895 in Nova Zagora in Bulgaria to a Ukrainian-Jewish family, she spent her childhood in Kyiv and then in Geneva where the family moved in 1897. Her mother Debora Perlmutter was a philosopher who taught at university; her father, Daniel Pasmanik, a surgeon, became a leading theoretician of Zionism in the Russian Empire. A fervent anti-Bolshevik, Pasmanik fought for the White Army in the Russian Civil War. In Switzerland, Bespaloff (then Rachel Pasmanik), studied piano and composition at the conservatory, philosophy at the university, and eurythmics with Émile Jaques-Dalcroze. These three areas of study are all entwined in her existential philosophy of embodiment.

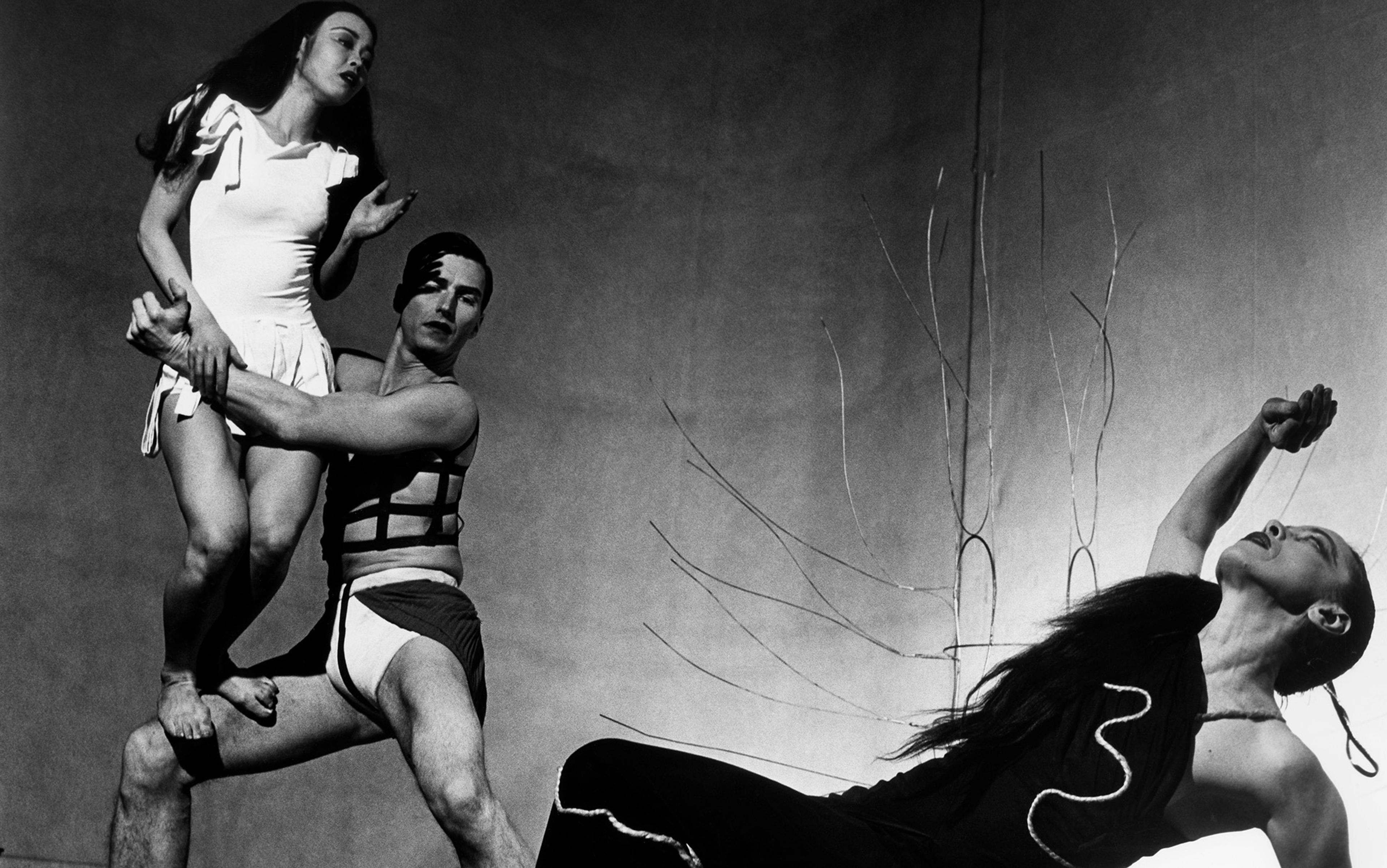

Dalcroze eurhythmics is a holistic method of musical education; it turns the body into an instrument. Different temporalities are concretised through movements, arm gestures and steps. For Bespaloff, eurythmics became an intimate practice of listening with her entire body. Dalcroze’s favourite student, she was sent to work in Paris in early 1919. She began teaching eurythmics at the Paris Opera while also publishing short texts on dance. Bespaloff’s ‘plastic dance’ aimed to restore a lost dynamism. Her method attracted the attention of Jean Cocteau and Sergei Diaghilev, who introduced this new corporeality to his Ballets Russes. If philosophy sharpened her ears, eurythmics sculpted her body towards an embodied experience of temporality. She believed that a more authentic sense of time, lost in modernity, still lurked beneath our skin.

‘She listened with her whole person: with her hands, with her lips, with her eyes’

In 1921, Bespaloff was the choreographer of the ‘Royal Hunt’ scene in Hector Berlioz’s opera The Trojans – a theme she would return to in her Iliad essay. In ‘Dance and Eurythmics’ (1924), Bespaloff wrote that dance is a universe with ‘its vocabulary, a fixed language, its own logic, its needs.’ Eurythmics is the system of this universe, turning movement into existential experiences. Through the plasticity of our bodies, we can reach new forms of being. In the fragment ‘The Dialectic of the Instant’, Bespaloff describes time consciousness as ‘nothing other than a certain way of grasping the relationship between finitude and infinity in the instant.’ The instant’s brevity points us towards a lost continuity that can be restored. Through music and dance, Bespaloff discovered what she calls the experience of ‘magic interiority’. By externalising movement, the subject of eurythmics plunges herself into an inner experience.

Bespaloff met her second important teacher in 1925, the Jewish existentialist philosopher Lev Shestov (born in Kyiv as Yehuda Leib Shvartsman). The encounter with Shestov changed her life: Bespaloff the choreographer decided to become a philosopher. This was a radical move but, by then, she was already married to a Ukrainian businessman, which allowed her to quit her job at the Opera and soon after have a daughter. Shestov was a central figure in the philosophical émigré circles of interwar Paris. French existentialism gained fame much later through the works of Sartre and Camus. However, Sartre was deeply indebted to Shestov’s original synthesis of Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, Dostoevsky and Jewish theology.

Shestov’s charisma and unsystematic thought magnetised young philosophers, among them Georges Bataille. In many ways, the Shestov circle was the hotbed of French existentialism. Along with the Romanian poet Benjamin Fondane, Bespaloff was at the centre of Shestov’s salon. Her friend Daniel Halévy described her sitting on Shestov’s sofa, completely motionless, while ‘she listened with her whole person: with her hands, with her lips, with her eyes.’ One of the few women in the circle, she soon became friends with the Christian existentialist writer Gabriel Marcel and the Jesuit theologian Gaston Fessard who both admired her work. A female philosopher in the 1930s was, as Olivier Salazar-Ferrer put it, ‘a bit like a woman in the 19th century wearing men’s clothes.’ However, Bespaloff would soon wear her own clothes. In 1929, she had dinner with Edmund Husserl whose phenomenology she confidently attacked with Shestovian arguments.

Bespaloff caused another stir with the publication of her ‘On Heidegger (Letter to Daniel Halévy)’ in La Revue philosophique in 1933. It was among the very first discussions of Martin Heidegger’s thought in France. Fluent in German, Bespaloff had read Heidegger’s Being and Time (1927) in the summer of 1932. Heidegger’s greatness, she wrote, was that ‘he situates himself in the inextricable; he does not want to detach himself.’ Similar to the experience of eurythmics, Heidegger’s philosophy proposes our hopeless entanglement with the world. It is not difficult to imagine a 28-year-old Sartre being drawn to Bespaloff’s letter, where she wrote excitedly: ‘Existence projects itself into the possible: choice is its destiny.’ For Bespaloff, interpreting Heidegger, this choice is not a matter of free will but of irrevocable commitment. By actively choosing, we dash beyond ourselves into an uncertain future.

As a musician, Bespaloff ‘listened’ to Heidegger’s text as if to a performance of Bach, a ‘monumental Art of Fugue’. She recognised that, as in a Baroque fugue, all the motifs ‘bring us back to the central theme of Being taken up in all its possible aspects, with increasing infinite variation, but always identical to itself.’ Bespaloff’s enthusiasm for Heidegger’s musical metaphysics was soon tempered by the discovery of another existentialist: Søren Kierkegaard. In 1934, she published notes on Kierkegaard’s Repetition (1843), a work that emphasised the musicality of repetition as continuous transformation.

She declares war on her teacher’s total denial of any possibility of truth

Repetition does not add anything, it only accentuates what is irreducible to human existence. Repetition in Kierkegaard is ‘the will to live again and the refusal to survive’. Only by repeating can we become authentic subjects. In Kierkegaard’s ‘beautiful moment’, Bespaloff found what she called ‘the instant’: an experience of absolute, eternal silence. The absence of a path, she wrote on Kierkegaard, is the only path his philosophy wants to follow. This Zen-like image also perfectly captures the meandering trajectories of her own thought, which Laura Sanò has called ‘nomadic’. A wandering cosmopolitan, Bespaloff was forced to traverse the boundaries of various countries, languages and cultures. Her philosophy mirrored that nomadism, with subtle attention to the embodied experience of movement, melody and metamorphosis.

Bespaloff’s essay collection Paths and Crossroads (Cheminements et Carrefours) appeared in 1938. Dedicated to Shestov, the book includes texts on Julien Green, André Malraux, Marcel and two essays on Kierkegaard. The chapter ‘Shestov before Nietzsche’ declares war on her teacher’s total denial of any possibility of truth. By refusing to think, she writes, Shestov had returned to another dogma – a radical relativism that ultimately turned into nihilism. Against Shestov’s rejection of reason, Bespaloff poses Nietzsche’s attempt to reach truth through and within one’s life. Nietzsche’s concept of the Will to Truth, she thought, could reconcile us to the tragedy of existence. Where Shestov saw an unbridgeable gap, Bespaloff made a leap: in the instant, happiness is in our reach. Bespaloff’s ‘happy consciousness’ made a deep impression on Camus who read the book closely in the summer of 1939.

Bespaloff’s writings on Kierkegaard coincided with the publication of Wahl’s Kierkegaardian Studies (1938) – a testimony to their friendship and lifelong collaboration. Bespaloff and Wahl were trendsetters in Paris. Introducing Kierkegaard’s anti-Hegelian philosophy into France, they prepared the ground for the existentialism that flourished in wartime Paris. Their ventures into Christian existentialism directly reacted to Hegel’s revival in France instigated by Alexandre Kojève’s lectures, held between 1933 and 1939. Another émigré from the Russian empire, Kojève was as pivotal as Shestov to the formation of French modernism. It was these refugees from eastern Europe, among them Bespaloff, who shaped the course of French culture by importing new currents to Paris, including Surrealism, Marxism, phenomenology and existentialist philosophy.

In the spring of 1938, Bespaloff began rereading the Iliad with her daughter Naomi. Her extensive notes turned into a brilliant essay on Homer’s epic poem. Shestov’s death that year deeply upset her. In a letter to Wahl, she calls Shestov one of the few truly noble men she knew. The family moved to her husband’s estate in southern France in 1939. Just before the Nazis occupied Paris, she wrote a letter to Marcel: ‘But the worse it gets, the more I realise that you can’t love life, the more I discover the urgent need to find new reasons to love it. And I am afraid that this time I won’t be able to, which would be worse than death…’

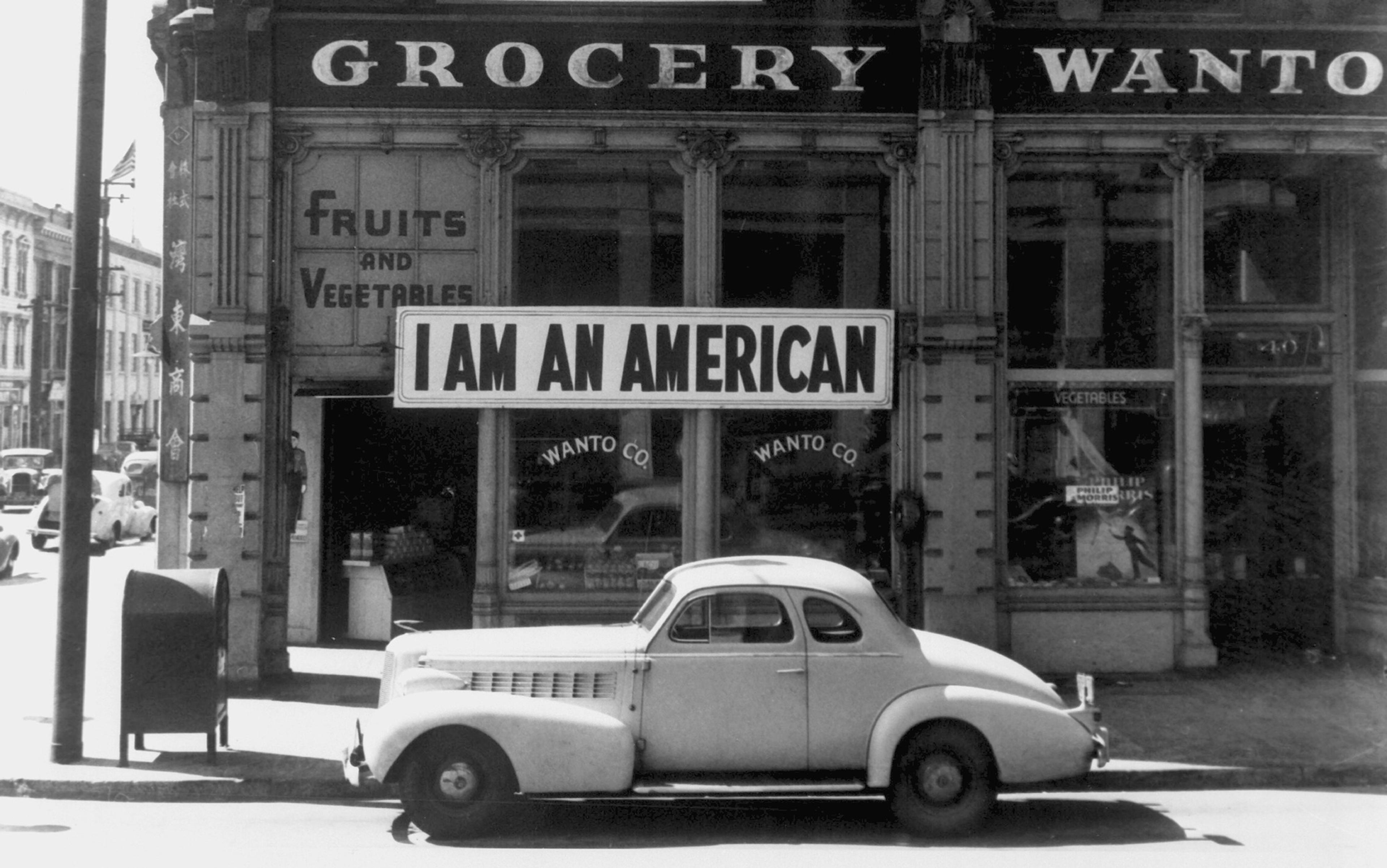

Her work on the Iliad essay became an existential ‘method of facing the war’. She soon became aware of a similar text, written coincidentally, that appeared in Cahiers du Sud in 1940: Weil’s ‘The Iliad, or the Poem of Force’. Bespaloff began to revise her essay; she critically responded to Weil’s condemnation of any use of force. Living as a Jew in Vichy France, Bespaloff became increasingly desperate, and with good reason. In November 1941, she wrote to Marcel: ‘I feel as if I am stuck in a sad, restless, absurd dream. And I am very afraid of waking up.’ Her friend Wahl, also Jewish, had been imprisoned and tortured by the Gestapo, and worse was to come for many Jews in Paris.

In 1942, Bespaloff managed to escape, boarding one of last ships to leave Nazi-occupied France, with her mother and daughter, her library and grand piano. Having narrowly fled a concentration camp outside of Paris, Wahl joined them. With his encouragement, Bespaloff began to rework her essay on the Iliad. She eventually finished her notes in yet another exile, this one in New York. Published in English translation in 1943, On the Iliad framed war as an absolute ‘question of losing it all to gain it all’. In the words of Fondane’s letter to his wife, war became ‘the moment to live our existential philosophy’. According to Bespaloff, Homer felt both intense love and intense horror of war. Where Weil claimed that force transforms subjects into objects, Bespaloff, emphasises brief moments of beauty that occur in the midst of violence. With war being waged all around, there are flashing instants of generosity and grace.

In the Iliad, force is both a supreme reality and an illusion. It is the superabundance of life itself, ‘a murderous lightning stroke, in which calculation, chance, and power seem to fuse in a single element to defy man’s fate.’ This does not mean that Bespaloff glorified violence. Far from it. But the experience of the Second World War made her realise the inescapability of force and its power to transform an individual’s understanding of the human predicament. At the heart of her essay is Hector, the ‘resistance-hero’ who embodies justice and courage. Like every human in the Iliad, Hector cannot flee his fate – and he knows it. Hector’s flight from force is short but has ‘the eternity of a nightmare’. That is the horrifying temporality of war that Bespaloff experienced first-hand.

Hannah Arendt’s reading of Kafka echoed Bespaloff’s existentialist despair

The most crushing parts of Bespaloff’s Iliad essay are dedicated to Helen, a woman with whom she clearly identifies. Clothed in long white veils, she is the most austere character of Homer’s poem. Both unbearably beautiful and unfortunate, Helen awoke in exile and felt ‘nothing but a dull disgust for the shrivelled ecstasy that has outlived their hope.’ She is the prisoner of her own passivity, forced to live in horror of herself. Ultimately, Helen’s promise of freedom, like Bespaloff’s own, remains unfulfilled. Helplessly, Helen watches the men who went to war for her, observing ‘the changing rhythm of the battle’. The breaks that interrupt the fighting are rare instants of silence:

The battlefield is quiet; a few steps away from each other, the two armies stand face to face awaiting the single combat that will decide the outcome of the war. Here, at the very peak of the Iliad, is one of those pauses, those moments of contemplation, when the spell of Becoming is broken, and the world of action, with all its fury, dips into peace.

While in New York, Bespaloff preserved her ties to Parisian intellectual life from her exile by exchanging letters with Fessard and Marcel. She got a job with the Voice of America’s French broadcast before moving to Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, where she taught French literature. Mount Holyoke became an important outpost for French culture in the US during the war. At gatherings of exiled scholars organised by Wahl, Bespaloff met Jacques Maritain, André Masson, Marc Chagall and Claude Lévi-Strauss.

This ‘small, dark lady who wore white gloves’, as her translator Mary McCarthy described her, also made an impression on Hannah Arendt who visited in August 1944 to deliver a lecture on Franz Kafka. Arendt’s reading of Kafka, later published in Partisan Review, echoed Bespaloff’s existentialist despair. Under the dark shadow of war, Arendt describes humanity as inescapably trapped in history’s meshes. Kafka’s ‘nightmare of a world’ had become reality. In an essay on Camus, her last published work, Bespaloff describes how history forced her generation ‘to live in a climate of violent death’.

After the war, despite previously having been fêted by them, Bespaloff became a vocal critic of the new generation of French existentialists, especially Sartre. In a 1946 letter to the musicologist Boris de Schloezer, Bespaloff wrote that ‘the hollowness of subjectivity that Sartre opposes to what I call “magical interiority” is much less the foundation of a new humanism than the harbinger of a new conformity.’ She argued that, instead of liberating the individual, Sartre’s existentialism destroyed the magical interiority through which humans can authentically connect with one another. For Bespaloff, Sartre degraded the subject into an object under the gaze of the Other. This objectified ‘subjectivity curiously aligns with American “individualism”, which unleashes itself in action to mask the absence of the individual.’ Like Helen’s Troy, the US felt both dull and hostile to Bespaloff.

Bespaloff’s journey to Mount Holyoke was her final exile. During term break, in April 1949, for reasons not entirely clear, she sealed her kitchen doors and turned on the gas oven. Her own complex fugue ended with a tragic cadence. She had written earlier of the happiness that can be found in an instant. In her final note, alluding to Camus’s claim, she wrote: ‘One can imagine Sisyphus happy, but joy is forever out of his reach.’