Just outside Paddington Station in London, on the side of a corporate building at 50 Eastbourne Terrace, there is a large clock. Glance at it twice and you will notice there seems to be a miniature man inside, in a three-piece suit, painting then removing the hands of the clock, calmly marking the day, minute by minute. At first, your head cannot organise an idea of how this has happened. Clearly there is no real miniature man inside. Then you understand that you are watching a film, the painstaking result of recording one man’s continuous 12-hour performance, which someone has had the wit to insert into this unremarkable piece of street furniture. Your final experience is of delight that this public clock – a largely redundant piece of architectural decoration in today’s age of mobile phones – has become a philosophical poem, with function intrinsic to its artistry. You are invited to experience time in its existential bareness, as a medium of human action.

The clock is the work of the Dutch designer Maarten Baas, who launched his Real Time project at the Salone del Mobile in Milan in 2009. A trade fair largely dedicated to product design – the best new taps, the most stylish new sofas – it has increasingly seen infiltrating its artier fringe festival (the so-called ‘Fuorisalone’) a whole species of ambiguous object where furniture meets sculpture. Here, what counts is less that the chair or light or clock is comfortable, bright or even beautiful: it must arrest attention like conceptual art. The idea, conceit or story behind it must equal the value of its materials or the ingenuity of its method of construction, which sometimes themselves become part of the salient narrative.

Among such iconic objects we might count the Dutch designer Jeroen Verhoeven’s Cinderella Table (2006). To create this, the young student fed into his computer the outlines of a sinuous 18th-century chest of drawers and an elegant table, both emblems of princely taste, to produce a hybrid conceptual object. It combines the profiles of both objects, visible at right angles to each other, and was painstakingly constructed in plywood by a firm specialising in boat building. The name evokes Walt Disney’s own fun with 18th-century furniture in films such as Beauty and the Beast and also the contrast between the humble material of the table and the luxurious woods and gilding of its grand antecedents.

Cinderella Table (2006) by Jeroen Verhoeven. Courtesy Brooklyn Museum

Another example are Nacho Carbonell’s gigantic irregular mesh and plaster lights, which grow like trees out of simple chairs, creating poetic cocoon-like spaces, evocative, to him, of his childhood home in Spain. Or Thomas Lemut’s sleek metal Gigognes. Olympia. 43 + 38 (2020) nesting tables, whose cracked glazed earthenware tabletops map the cracks in the varnish on the breast of Olympia in Édouard Manet’s scandalous 1863 painting, thereby marrying minimalist precision engineering with a gesture towards human flesh and frailty. These works puzzle, they tease. The more you look, the more you see, and the more their value as cultural objects comes into balance with their aesthetic appeal.

Gigognes. Olympia. 43 + 38 (2020) by Thomas Lemut. Courtesy Mouvements Modernes © Thomas Lemut

Detail of Olympia (1863) by Édouard Manet. Courtesy Musée D’Orsay, Paris

In many ways, it is obvious that furniture could be a direct expression of human thoughts and feelings. There is its closeness to the human body and its place at the heart of our domestic, social and political lives, both of which make furniture design a fertile medium for exploring the complexities of embodied experience. As the academic John A Fleming commented in ‘The Semiotics of Furniture Form’ (1999): ‘All the objects we make are inscriptions of the human body and mind upon the circumstances of time and space.’ Our closeness to moveable furniture – chairs, small tables – is further underlined by our anthropomorphising talk of the foot, the arm, the back, the head, the leg, the seat. The 17th- and 18th-century European cabinetmakers who rapidly expanded the types and styles of furniture were alert to the ways furniture might reflect contemporary interests. It’s not a huge step from 18th-century rococo furniture mimicking the natural forms their owners might encounter on their rural estates, to the Goodall Chair (2021) and its siblings, literally grown into chair shape by the botanical craftsmen Gavin and Alice Munro. Or compare the elaborate zoomorphic legs of much grand, 18th-century furniture with the exuberantly feminist chair The Grand Lady (2018) of the designer Anna Aagaard Jensen, with its assertively splayed legs.

Goodall Chair (2021) by Full Grown. Photo by James Harris, courtesy of Sarah Myerscough Gallery

Spring willow chairs growing in 2019

In the Chair Orchard

Finished chairs

The Grand Lady (2018) by Anna Aagaard Jensen. Photo by Daniel Kukla, courtesy of Friedman Benda and Anna Aagaard Jensen

Semioticians will tell you that all objects tell stories about the societies that produce them. Since the beginning of civilisation, thrones and crowns, the accoutrements of religious ritual and the varieties of stamped coinage have been valued for their symbolic as much as for their functional purpose. And as academics become better at interpreting the material cultures of early civilisations – their vessels, textiles, architecture, furniture and ornaments – so our awareness of their capacity to express a whole range of values and attitudes to the world has grown. But with the Renaissance’s valorisation of the fine artist, the entire class of often elaborately and thoughtfully constructed functional object has been consigned to the category of decorative art. It is valued for its beauty and workmanship, but viewed in contradistinction to the paintings and sculptures – the spiritual emanations – of artists such as Michelangelo and Benvenuto Cellini.

The distinction has been laboriously maintained by the traditional linguistic and educational divides between design and art, enforced within art colleges. In What Is a Designer? (1969), the cabinet maker and poet Norman Potter wondered aloud: ‘Is a Designer an Artist?’, admitting that ‘in the last analysis, every human artefact – whether painting, poem, chair or rubbish bin – evokes and invokes the inescapable totality of a culture, and the hidden assumptions which condition cultural priorities.’ Still, he wanted too to make plain ‘that a designer works through and for other people, and is concerned primarily with their problems rather than his own.’ The idea that it might be legitimate for a designer to seize hold of her task and run with it, not just to serve her customer but to express her individual thoughts and emotions, didn’t occur to him.

They tapped the potential of furniture and other functional objects to become the very embodiment of myth

Potter’s view is consonant with the values of 20th-century modernism, which at the same time as making a democratic hero of the industrial designer, stripped furniture and other functional objects of their right to express anything other than their function. But there were countervailing movements in the early 20th century that resisted such rigidity: the Bauhaus and the Wiener Werkstätte, influenced in part by the ideas of William Morris and John Ruskin, passionate instigators both of Britain’s 19th-century Arts and Crafts movement, who sought to bring art, craft and industrial design closer together, and Russian Constructivism and De Stijl in the Netherlands, which also embraced the opportunity of industrial manufacture to renegotiate traditional boundaries.

More radical were the Surrealists. The French sociologist and philosopher Jean Baudrillard commented in The System of Objects (1968):

The world of the objects of old [he means pre-Industrial manufacture] seems like a theatre of cruelty and instinctual drives in comparison with the formal neutrality and prophylactic ‘whiteness’ of our perfect functional objects.

In consequence, he says, the ‘repressed gestural system is thus transformed into myth, projection, transcendence.’ But there were those who resisted that repression, tapping the potential of furniture and other functional objects to become the very embodiment of myth – schooled projections of the subconscious. Think of Salvador Dalí’s Mae West lips sofa and his lobster telephones, created in the 1930s for his patron Edward James; Méret Oppenheim’s Object (1936), known in English as ‘Breakfast in Fur’; or Dorothea Tanning’s series Primitive Seating (1982) – animal-print covered chairs, complete with tails! Such work opposed both rationalism and conventional luxury.

In an interview about the show ‘Objects of Desire: Surrealism and Design 1924-Today’, which travelled from the Vitra Design Museum in Germany to the Design Museum in London in 2022, its curator Mateo Kries spoke about Surrealist design as transgressive:

because it rejects the definition of design as merely an industrial practice, as a service by a designer for a manufacturer. It’s looking at design as something that can involve speculation, and even contradiction.

The Surrealists were not alone in pushing boundaries. Even prominent modernist designers – including the Dutchman Gerrit Rietveld, the Finnish designer Alvar Aalto and the French architect-designer Charlotte Perriand – were stretching the forms and materials of furniture in sculptural ways.

There were shifting responses to the monolith of mass production in the United States as well. Take Wharton Esherick’s revival of hand-crafted wooden furniture, or George Nakashima, renowned for his tables consisting of irregular slices of ancient tree trunk: both expressed a keenness to embed humans once again in nature. Or figures like Isamu Noguchi and Ray and Charles Eames who moved freely between sculpture, architecture and design. In fine art, too, artists and sculptors seized on humble furniture as synecdoches for human presence and physical reality, partly in reaction to the epic, self-involved canvases of the Abstract Expressionists. In Pilgrim (1960), Robert Rauschenberg presented us with an abstract painting where paint spills off the canvas onto a simple chair placed in front, thereby initiating the chair into the world of myth and story conjured in the canvas. However you look at it, the salience of furniture as a conduit for human emotions and signifier of ideas was widely recognised.

Pilgrim (1960) by Robert Rauschenberg. Courtesy and © The Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Some artists, such as Scott Burton, consciously set out to be both artist and furniture designer at once. Inspired by the earlier 20th-century boundary-crossing movements, Burton made refined steel furniture that combined a monumental simplicity with clear functional purpose. Most of his peers, however, felt they had to be one or the other – or both, but not at the same time. Donald Judd, for instance, fought to keep his minimalist sculptural works and his furniture (sometimes fabricated by the same people in similar materials!) entirely separate, critically and commercially. In his essay ‘It’s Hard to Find a Good Lamp’ (1993), Judd wrote:

The configuration and the scale of art cannot be transposed into furniture and architecture. The intent of art is different from that of the latter, which must be functional. If a chair or a building is not functional, if it appears to be only art, it is ridiculous.

Indeed, Judd began making furniture as a practical expedient, despairing at the ‘junk for consumers’ available in furniture stores. But from an outside perspective, his furniture clearly expresses ideas that cross over with those embodied in his sculpture – and it is hardly comfortable. Judd’s furniture also shows clear debts to the iconic pieces of Rietveld, Aalto et al, whose work he collected. As others have pointed out, part of his aim in drawing a clear line between the motivations behind art and furniture was his anxiety that his minimalist conceptual artwork might in fact be mistaken for design: those beautiful machine-engineered columns of boxes commandeered for knickknacks.

These objects became vivid as artworks only when touched, held, worn, carried

Other artists had no such anxiety. The Austrian artist Franz West developed a practice in the 1960s and ’70s that included abstract sculpture, interactive sculpture, furniture and collage. Using found materials and roughly cut materials, he welded eccentrically shaped furniture that he would place in museums and invite visitors to test-drive. In an interview with Iwona Blazwick from 1991, quoted by Alex Coles in DesignArt (2005), West challenged Judd head-on:

Don Judd said that a chair and a work of art are completely different. My understanding is that it is absolutely not different. If I make a chair, I say it’s an artwork.

Perhaps West’s most original contribution to 20th-century art was his Passstücke (Adaptives). In 1973, he began creating compact, portable sculptures using materials such as plaster and papier-mâché. These objects became vivid as artworks only when touched, held, worn, carried, or otherwise physically or cognitively engaged. The engagement of the viewer’s body was critical. ‘The perception of art,’ West once said of his couches, ‘takes place through the pressure points that develop when you lie on it.’ In his self-appointed role as a thorn in the stiff sides of Austrian society, West saw the potential of furniture to offer space for the contingent, battered human body in the palace of fine art.

From the Franz West exhibition at Tate Modern, London in 2019. Courtesy ACME/Flickr

The US sculptor Mike Nevelson was likewise clear that his interest in furniture stemmed from its connection to the human body:

I do not make furniture, or sculptured furniture or furniture sculpture. I am a sculptor who makes sculptures whose shape comes from interpretations of memories of furniture that originally had an anthropomorphic basis.

From a different end of the US spectrum, Wendell Castle, who made his reputation making powerfully sculptural, biomorphic furniture, also saw himself as an artist. He once told The New York Times: ‘I thought of the work as sculpture, not furniture,’ adding: ‘The fact that it was useful didn’t add anything to it, for me.’ Eschewing conventional furniture-building methods, such as joinery, his pieces were created from simple hand drawings using a chainsaw and robot to carve large blocks of laminated wood. By the 1980s, Castle was exploring the expressive potential of resin, and its myriad colours, though in the last decades of his life (he died in 2018) he returned to wood, and that ultimate sculptural medium, bronze. Although he worked like a sculptor, the human body and its potential for physical interaction with the piece was always in mind. Part of the delight in his pieces is the way the viewer’s imagination leaps to occupy the spaces it provides, to enjoy its accommodating curves – even if so much of his furniture is physically off-limits, in museums or private collections.

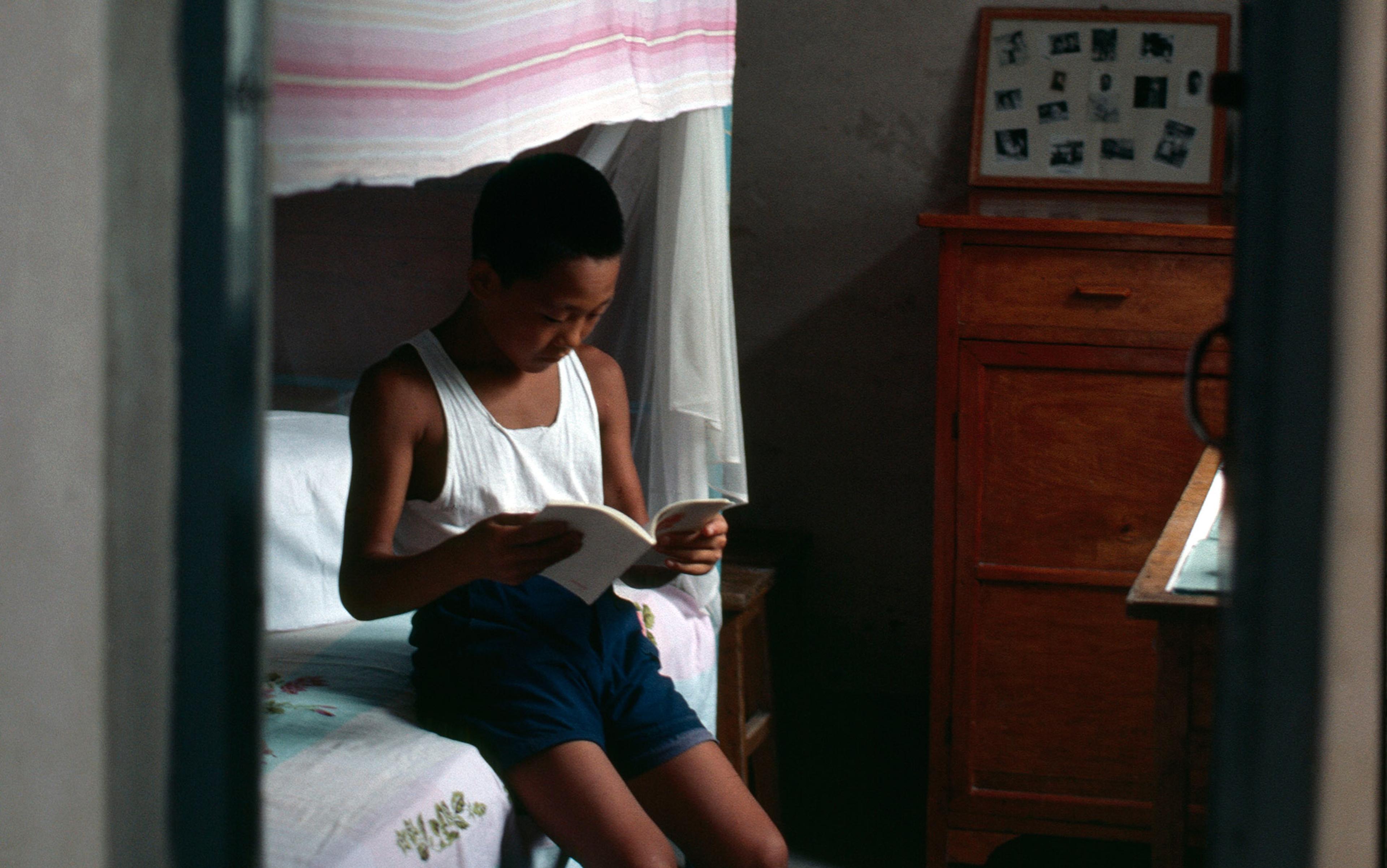

Ron Arad is a UK-based artist who has long tested the borders of art and design. His 1987 exhibition in the Edward Totah Gallery in London featured chairs, concrete hi-fis and telescopic aerial lights that were as much about furniture as being it. Arad made his name with the Rover Chair created in 1981. Inspired by Pablo Picasso and Marcel Duchamp’s ready-made sculptures, he fused a leather-covered Rover car seat picked up in a scrapyard with tubular steel and Kee Klamp joints. The ingenuity and wit of its construction caught the spirit of the time – Friends of the Earth featured it on the cover of its magazine. His Bookworm (1993) spiral bookcase brought poetry into industrial design, creating a curving shape that evokes the curled-up body reading a book, while gesturing towards the kind of inwardness you get with the experience of being lost inside a book. Considering these various ways that furniture makers turn provocateur, it is tempting to ask if perhaps furniture becomes art when it dialogically implicates the body, as opposed to merely catering to the body’s needs.

Bookworm (1993) by Ron Arad. Courtesy Diane Jones/Flickr

The group who did more than anyone to liberate furniture from the strict protocols of product design was the Dutch company Droog. In 1993, the art historian Renny Ramakers and the product designer Gijs Bakker joined forces to take a group of experimental young Dutch designers to Milan, to exhibit their work at its prestigious furniture fair. To signal the peculiar quality of their sense of humour, they called themselves Droog or ‘dry’. Their show was the talk of the town, with iconic pieces such as Tejo Remy’s ‘You Can’t Lay Down Your Memory’ Chest of Drawers (1991), made of found drawers, each with their own history, held together roughly by a belt, or his first Rag Chair (1991), constructed from piles of recycled textiles strapped together into a chair shape, offering a stimulating challenge to Italian opulence.

Rag Chair (1991) by Tejo Remy. Courtesy Droog

In Moving Objects: A Cultural History of Emotive Design (2023), the design historian Damon Taylor notes that the importance of such objects (and many others discussed here) depends on their ability to communicate ideas more than on their functionality. As such, their impact has been hugely abetted by digital communication. Taylor argues that our relationship to such unique and startling objects has changed fundamentally as their images have migrated from niche design publications to the internet and Instagram. The hand-built craft aesthetic, suited to one-off or very limited production, would normally have condemned these pieces to obscurity, but in fact it is precisely their singular or limited-edition nature that lifts them into an authentic communication. Once there are many, the freshness of the story is lost. And while the one-off piece is normally seen as elitist (only one person can own it, after all) when its value lies in its power to tell stories, as carried by an image, it becomes truly democratic furniture, equally available to all. Of course, this cultural currency in turn enhances the value of the physical work for the single owner – an irony not lost on designers such as Job Smeets, whose Robber Baron (2006) series of furniture is today owned almost exclusively by robber barons.

Robber Baron Lamp from the 2006 series by Job Smeets. All photos by Robert Kot/Studiojob

Robber Baron Mantel Clock

Robber Baron Jewel Safe

Droog was one offshoot of an educational experiment – the radical programme of design teaching at the Design Academy Eindhoven (DAE) in the Netherlands, which encourages students to see design as a means to address and express many different ideas. Here, Bakker taught Richard Hutten and Jurgen Bey, who in turn taught Baas. Other graduates include Smeets of the Antwerp-based Studio Job, and Wieki Somers and Dylan van den Berg of Studio Wieki Somers. In a recent interview with Carbonell, the Spanish designer commented:

In Eindhoven, what I learnt was very poetic, and the school allowed it to come through. Here, I work with soul, emotion, a story to tell.

The danger is that people pick up on the spectacular look of such works but miss the thought

Pupils who cite Carbonell as an influence include Benjamin Motoc, a recent graduate from Paris, who described in an interview in 2021 the difference between the design education available at DAE and the more rigid curriculum at his previous design college:

[The French tutors] didn’t speak much about how political your work can be, how it can empower people – and how design can contribute to culture and how design can be art. There was no suggestion that design is not always for the masses, that it can be for communities. This is something I learned at DAE.

The belief that design can speak of politics and communities has erupted elsewhere too. In Brazil, two brothers, Humberto and Fernando Campana, founded their company in 1984. They were inspired by Brazil’s own characterful modernist design movement, headed by the architect Oscar Niemeyer, but also by a playfulness and chaotic openness to different influences, materials and techniques arising from their upbringing in the countryside near São Paulo. The Campana brothers transform waste or humble materials into outrageously colourful and intriguing furniture that carries its politics – environmentalism, sustainability, community – lightly. Humberto has said of the surrealist element in their joint work (sadly, Fernando died in 2022):

[W]e always speak about dreams and fantasies; we are storytellers. Even to this day, I still question what I am. Am I a designer or an artist? I don’t care to know, but I have the passion to create my experiences and to show my emotions.

In the past two decades, contemporary, ambitious, conceptually driven furniture has found fans. Commercial galleries and dedicated art fairs have proliferated; auction houses have begun to sell critically acclaimed pieces on the secondary market. In all their wide variety, however, these objects remain hard to define: are they art, are they craft, or even design? The fact that they have not fully found their place in the cultural sphere – that their ambiguity provokes anxiety – is evident in the confusion at art fairs and auctions about how this kind of expressive furniture is to be categorised. Which is usually alongside antique furniture and other decorative arts. Even some museums, whether of design or decorative arts, have taken a while to acknowledge their cultural value. Yet, as the boundaries between media and genre dissolve across all art forms, that recognition is likely to grow.

The danger is that people pick up on the spectacular look of such works but miss the thought. The critical distinction is easily lost between good pieces (where the furniture expresses an idea satisfactorily and its being furniture is part of the meaning) and those where there is just a flippant Oh yes, this is a piece of conceptual furniture because it looks a bit wacky and has a high price tag. And yet conceptual furniture is a thing. Take the work of Lubna Chowdhary, who uses the vernacular of furniture design (or ceramics) to create sculptural objects that interrogate a whole range of ideas relating to function but which are not themselves functional. Her work is indisputably sculpture. Thought-provoking, yes, but not because of its graceful balance on this particular tightrope.

From the Erratics series 2022 by Lubna Chowdhary

All images © Lubna Chowdhary

There is not just one way to work. Sometimes, the thoughtfulness is expressed at the level of materials, sometimes at the level of composition, sometimes in dream or fantasy. The design critic Rick Poynor, in his essay ‘Art’s Little Brother’ (2005), offered one account of the appeal of the best pieces:

The mystery comes from the way that our expectations of form’s conventional possibilities and limits are overturned. The sensory, intellectual and emotional satisfactions they offer as pieces to look at, think about and react to – as well as to use – are akin to the experience of sculpture.

He adds that, while art and design exist ‘in a continuum of possibilities’, ‘The most interesting work often happens in the gaps where there is room for manoeuvre and scope for debate.’ It is a highwire act. Lean too much towards function, and the idea seems a tag-on. Lean too far the other way, and it becomes just sculpture. When it works, the hairs stand up on the back of your neck. And you sit down.