In 1986, my quiet life as a doctoral student in philosophy was punctuated by a trip to Brno in Czechoslovakia (as it then was), where I found myself in a high-speed, chicken-scattering taxi, chasing a bus before it reached the border. It was my small part in a larger story of philosophers’ derring-do during the Cold War.

The Oxford philosopher of science Bill Newton-Smith had been arrested prior to my trip in the middle of a talk in Prague, taken to secret police headquarters for interrogation, then driven in a convoy through the snowy night to the West German frontier and expelled. The French deconstructionist Jacques Derrida had been followed for days, drugs were planted in his suitcase, and he was briefly arrested and detained at the border as a smuggler.

In order to understand the larger story, we must begin with the first efforts of the philosophers who helped start the independent and completely above-board Inter-University Centre (IUC) in Dubrovnik in the former Yugoslavia. Once we understand this larger story, we shall find a moral for some of our present complex ethical and political situations.

The IUC was founded by 30 universities in 1972, under the leadership of the physicist Ivan Supek, at the time rector of the University of Zagreb. Tito’s Yugoslavia, not aligned with the Soviet Union but communist enough to please it, provided neutral ground where academics from Warsaw Pact countries could meet their colleagues from the West. The IUC arranged conferences and courses in the humanities and social sciences, and soon moved into the natural sciences and medicine. There were some constraints.

In philosophy, technical subjects such as logic were more acceptable to the Warsaw Pact governments than ethics, unless the latter was done from a Marxist perspective. The Soviet philosophers, especially, were wary of speaking freely about non-technical matters to the foreigners. Newton-Smith and his Oxford colleague Kathy Wilkes, who had leading roles in the IUC’s birth and development, ran an annual Philosophy of Science Seminar, which I attended both as a final-year undergraduate from the University of Lethbridge in Canada and while studying for the DPhil in Oxford. These philosophers were focused on science and seemed uncontroversial enough to the authorities to fit the bill. But even talking about the philosophy of science allowed an entry-point into political conversations. Those were the days when the sociology of knowledge was flying high and the discussion was often about the values and politics that drove science and whether we could even make sense of the idea that science is a search for the truth. No one, however, encountered any trouble, at least not that I know of.

An undergound Hebrew class conducted by the theologian and Charter 77 signatory Milan Balabán. All further photos are © and courtesy the archives of the Department of the History of Antitotalitarian Culture, Moravian Museum, Brno, Czech Republic

While the IUC went on as ever, another set of activities, this time covert, began in 1978, after the Czech dissident philosopher Julius Tomin wrote a letter addressed to the universities of Oxford, Harvard, Freiburg and the Freie Universität Berlin outlining the hardships endured by Czech academics. Tomin explained that Czech philosophers came from a background heavy in Greek philosophy and that this was being curtailed – ‘from time to time we hear threats: “We will destroy you together with your Plato”.’

The marathon sessions, sometimes in Tomin’s flat, often lasted six hours

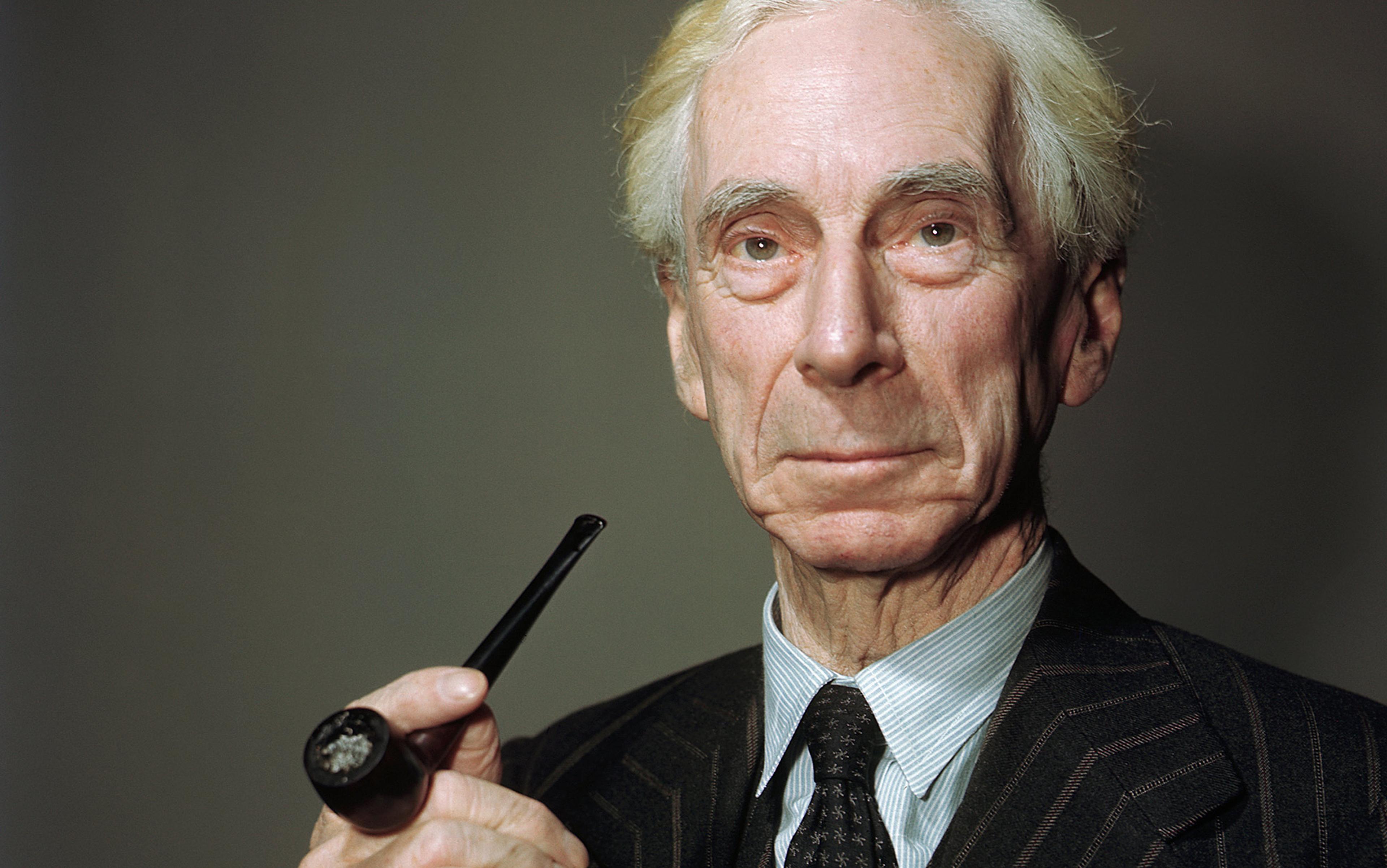

The threats were real. University education was heavily controlled and censored; state functionaries decided who could study and who could teach, and what they might study and teach; academics were subject to long sessions of questioning at secret police headquarters; mail was intercepted; those deemed dangerous were sacked. Tomin was running underground philosophy seminars out of his apartment in Prague and asked these distinguished universities to ‘enter into scientific contacts’ with the persecuted academics. Oxford answered his call – the Sub-Faculty of Philosophy voted to support the effort both financially and by sending their people to lecture at the underground university. Wilkes and Newton-Smith as well as Richard Hare and Charles Taylor were the first to visit, on benign tourist pretexts, and Anthony Kenny followed soon afterwards. They talked about the things in which they were expert – philosophy of science, René Descartes, philosophy of mind, all somehow considered threatening by the authorities.

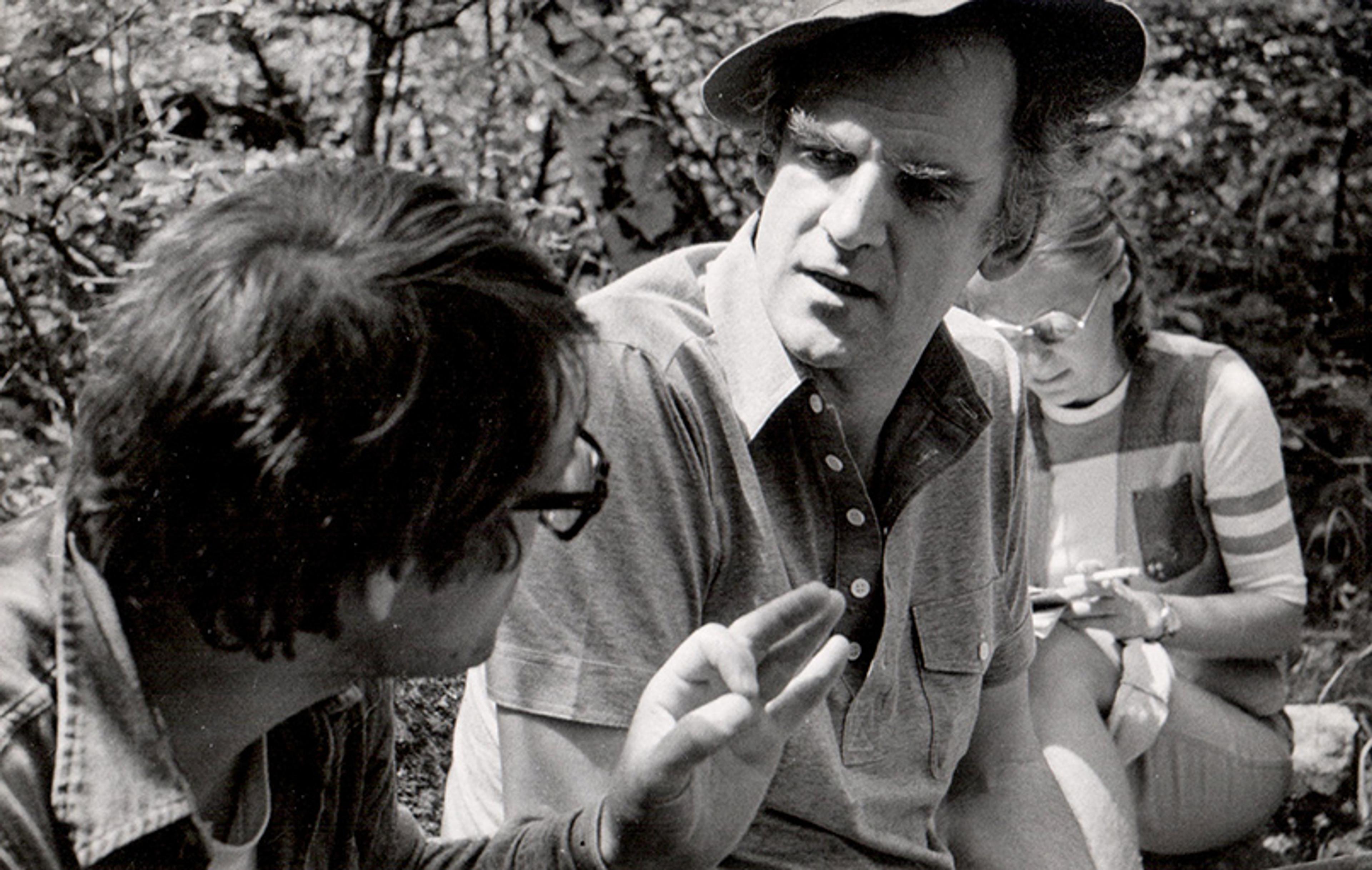

Philosophy wasn’t the only subject matter for the underground university. Ecology (especially the sensitive topic of environmental degradation or pollution), religion, literature and political science also figured heavily. The marathon sessions, sometimes in Tomin’s flat, sometimes in the homes of others, often lasted six hours. The locals, mostly large crowds of students and former (ie, fired) professors were hungry for all manner of ideas, taking full advantage of the presence of the visitor. An interpreter provided simultaneous translation.

Courtesy Moravian Museum

By 1980, the underground lecture movement felt it had to expand beyond Oxford and become a registered charity. The Jan Hus Educational Foundation was set up, named after the Moravian reformist priest and rector of the University of Prague, whose life straddled the 14th and 15th centuries. The Foundation was an alliance of the political Right and Left. It included Roger Scruton, a highly conservative champion of traditionalist values, the Left-wing anti-communist Wilkes and Newton-Smith, and Derrida, who sometimes referred to his deconstructionism as a radicalisation of the spirit of Marxism. One would think the alliance would be unholy and fraught but, in fact, the philosophers, despite their varying political views, were united in their efforts to improve conditions for colleagues in totalitarian regimes.

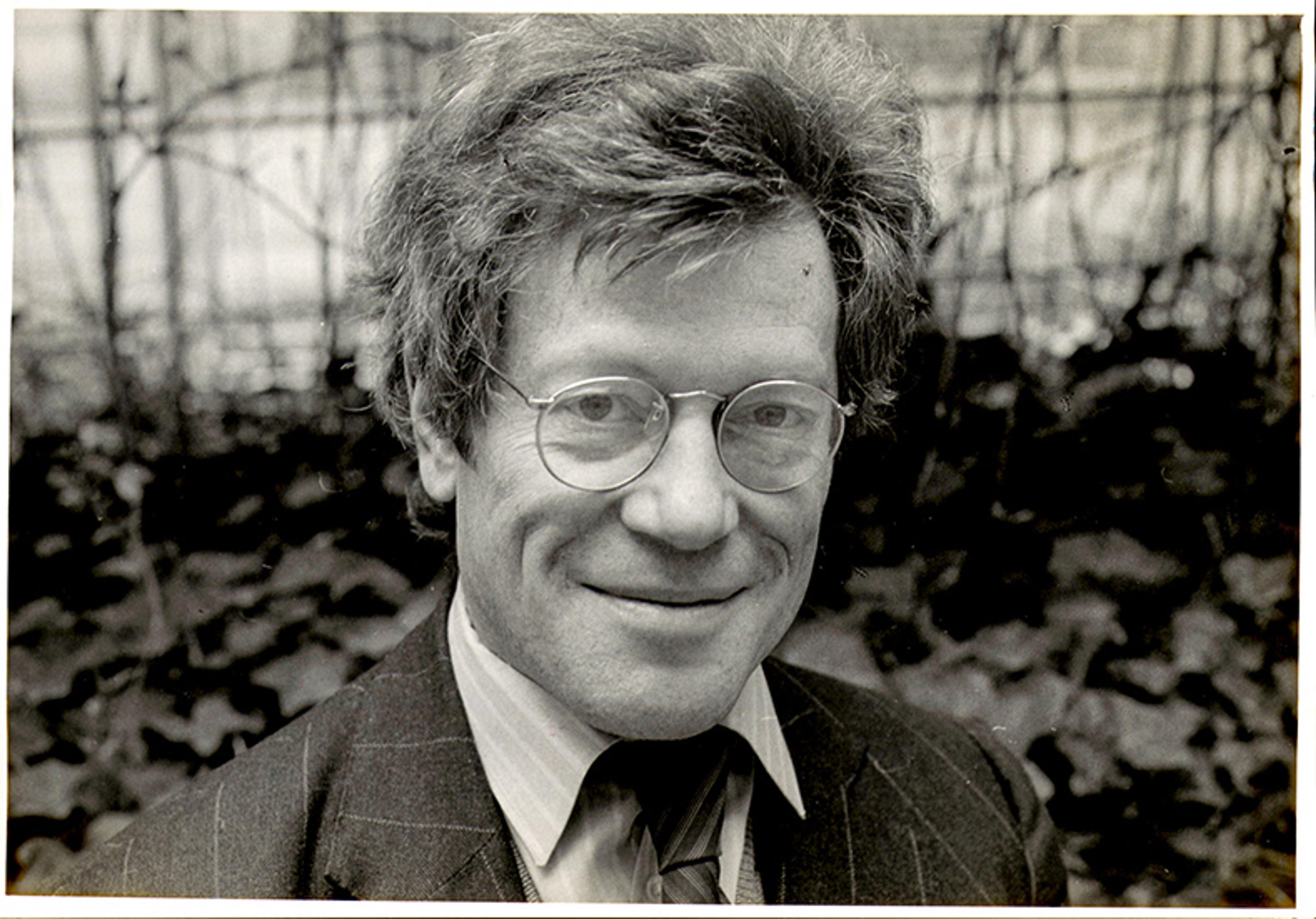

Roger Scruton pictured in the 1990s. Courtesy Moravian Museum

The scope of activities expanded as well. A three-year pathway was put in place for students to write exams and get a diploma from the University of Cambridge that might be of use to them in some future state of the world. At its most risky, the Jan Hus academics became smugglers. The contraband included books and photocopy machines, along with replacement fluid and spare parts, to enable samizdat (ie, clandestine) publications. It also included more mundane things requested by their hosts. When I went on my Brno mission for the Foundation, I brought in video cassettes of popular movies and cash in order to provide stipends to the unemployed and unemployable Czech seminar organisers.

These activities were not welcomed by the authorities. During the first years, the secret police would tail Jan Hus visitors from Prague airport, as they had access to flight lists. They stationed themselves outside the seminars, checking identity cards, so that they could expel student attendees from their universities and menace those who had already lost their positions. The Cold War had turned very hot in Czechoslovakia in the summer of 1968, when the Soviet Union sent in the army to brutally stamp out the reformist Prague Spring – in which new rights and freedoms of speech and travel had been given to the citizens of Czechoslovakia and the economy was partially decentralised. (The Hungarian Revolution had been similarly beaten down in 1956.) Artists, musicians, university students and professors were involved in those uprisings and, when things went back to their grim normal, these people found themselves, more than ever, in the crosshairs of the regime.

Derrida and others started to suffer the heavy hand of the Czech authorities

Tom Stoppard portrayed the atmosphere brilliantly in his play Professional Foul, written and broadcast in the late 1970s, in the shadow of the harassment and imprisonment of another playwright (Václav Havel) by the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. In Professional Foul, Professor Anderson, an eminent but selfish Cambridge philosophy don, attends a conference in Prague. A former student, who has returned to Prague where he is reduced to cleaning toilets as punishment for being a dissident, asks him to smuggle to England a thesis he has written, about the relationship between the rights of the individual and the rights of the community, in the context of the constitution of Czechoslovakia and its totalitarian government. Anderson refuses, on the shallow grounds that he has accepted the state’s hospitality and it would be bad form. He then gets a terrible first-hand glimpse of how things really are when his student is arrested and his family terrorised. When Anderson weakly challenges the actions of the police, he is assured by them that ‘we do not have laws about philosophy’ and that the crimes of his student are about something else, something non-political. But this is obviously false, even to Anderson. The next day, he reads out a good chunk of his student’s thesis to the conference instead of his own paper. The authorities revert to a tried-and-true method of suppressing speech – by pulling the fire alarm. Anderson manages to smuggle the thesis out of the country by placing it in the bag of a colleague.

Stoppard’s play is about how ethical dilemmas arise in practice. It is brilliant in many ways, including its skewering of a certain ordinary-language style of doing philosophy. An excellent dramatisation is easily accessible and well worth watching today, as we academics struggle with what to do about calls for boycotts, and how to act on our ethical and political principles:

Professional Foul was not a parody. The Jan Hus Foundation was declared a ‘centre of ideological subversion’ by the Czech police, and Newton-Smith, Derrida and others started to suffer the heavy hand of the Czech authorities. Some of those stopped at the border had been caught with the contact details of their Czech counterparts, which had terrible repercussions for their contacts and made the enterprise even more high stakes. Efforts were ramped up to prevent detection. I remember hearing stories of Wilkes, who walked with difficultly after a long-ago accident, careening around various Slavic cities, leading the secret police on winding routes to cafés, where she would then settle in for hours on end, with some rough wine as company.

The Jan Hus work expanded to other cities, with Brno being the second Czech outpost. Visitors could fly into Vienna and purchase a bus ticket there, avoiding detection, and then travel into Czechoslovakia. My own covert mission for the Foundation took place during this time. I was required to memorise pages of messages about photocopier parts, arrangements for future visits and payments, and so on, that needed to be relayed to my contact, JM, and then to memorise his replies to the Foundation. It took days to develop mnemonics for the outbound trip but, on the way back, I had only a few hours. Still, one could no longer be caught with incriminating evidence and even those with poor memories, such as mine, had to manage.

Charles Taylor conducts an outdoor seminar in an undisclosed rural location. Courtesy Moravian Museum

My trip was a combination of the serious and the absurd, as were many of the philosophers’ excursions. During Newton-Smith’s enforced snowy drive to the German frontier, the Soviet-made car broke down and he was the only one who knew how to fix it, which he did. On the serious side of my own excursion, I was bringing in a considerable amount in pounds sterling, which was bound to raise suspicion if I was searched. I was also warned that letters incriminating my contact had gone missing in the post and ‘while there is no reason to believe that these are in the wrong hands, there is always a possibility’. There was a script if either I or my contact were caught: ‘Should a messenger be detained and questioned … JM would like her to explain her visit as follows: she is a tourist in Brno, and is simply bringing greetings to JM from [a friend who emigrated to the UK a decade ago]’.

There was then the high-speed chase, scattering chickens in small villages

But, in fact, my touristic cover was rather flimsy. I was supposed to be a student visiting friends in Vienna who wanted to take a side trip to Brno because I was interested in Moravian beer. I told Scruton, who was in charge of such details, that this was a terrible cover story. For one thing, I had a very expensive air ticket from London to Vienna, then a bus journey from Vienna to Brno, with the entire round trip completed within three days. And there were those video cassettes, Amadeus and Easy Rider, which were not easy to explain. I decided to say, if questioned, that I found the cassettes on a bench at Heathrow. I also suggested to Scruton that I try to leave my ticket (in those days they were paper and lost at one’s peril) at the Vienna airport, only to have him sneer at the plan as being impossible. On the day, I simply asked the nice woman behind the British Airways desk if she might hold on to it for me until I returned in a couple of days. She cheerfully agreed, with only a mildly sceptical look.

It is this absurd side that has taken me through many a dinner party. JM went to great lengths to shake off a potential tail by foot and then car, accelerating around corners before coming to sudden stops. Then we sedately drove to his mother’s house for a slap-up lunch. This was especially odd, since my notes from the previous visitor said that ‘JM explains that his home is especially subject to search during a meeting’. Why his mother’s place was deemed safe was beyond me.

Most absurdly, or perhaps most seriously, JM and the hotel clerk were wrong that my dawn return bus from Brno to Vienna would leave from the bus stop at which the inbound vehicle had dropped me off. Since I couldn’t understand the little notice that informed one about the change of location, I waited in the gloom and missed my transport. It seemed that I would also miss my flight and then incur unwanted knock-on absences in Oxford the next day. But mostly, I just wanted to get out of there. Someone who spoke some English came to my rescue by flagging down a taxi and explaining to the driver the need to catch the bus before it reached the border. There was then the high-speed chase, scattering chickens in small villages. We caught up with the bus with the frontier in sight, and the taxi driver forced it to come to a halt, with me distributing crisp pound notes to both drivers.

I picked up my ticket from the British Airways counter in Vienna and headed back to the sedate world of Oxford philosophy, my mission completed.

In 1990, the rationale for the Jan Hus Foundation and other Cold War philosophy initiatives changed with the times. The Berlin Wall fell in 1989. Yugoslavia was torn apart by the Homeland War. George Soros brought the Central European University (CEU) into being in 1991 (and, I think, had helped fund the Dubrovnik IUC as well). The CEU had campuses in Budapest, Prague and Warsaw. Wilkes and Newton-Smith were there for the inception of the CEU, and Newton-Smith ran it for the first two years. It had to close the Prague and Warsaw campuses when the political winds started to blow against it. They recently blew strong again in Budapest, with the authoritarian Victor Orbán government forcing its move to Vienna.

Both the Right and the Left had boycotting urges during the Cold War, urges that we see front and centre in some of our most challenging political problems today. Some anti-communists on the Right were inclined to isolate academics in enemy countries, with the aim of forcing change on their governments’ policies. Some on the Left felt the same way during the later civil wars when the authoritarian nationalist Franjo Tuđman became the first president of Croatia. Wilkes and the Canadian philosopher of science Jim Brown had a tiff with the Oxford philosopher Michael Dummett after inviting him to the IUC in Dubrovnik. Dummett, a true paragon of human rights, chastised Wilkes and Brown for being involved with anything in Croatia. They tried to explain the complication: Tuđman wanted to turn the IUC into a centre for Croatian studies, a centre for reactionary politics. By attending the IUC, foreigners supported its internationalist outlook and its independence from the government.

Dummett was unmoved. But we should listen carefully to what the Jan Hus philosophers, sadly mostly gone now, have to say to us today. Often terrible regimes don’t care about professors and students but, more often than not, they would like to tame them. Often, professors and students in terrible regimes are trying to effect change from within. The lesson of the Jan Hus philosophers is to ‘enter into scientific contacts’, however much the politics of the regime might stick in your craw. Today, as the United States Congress bears down on universities for pro-Palestinian activities, and some students and faculty call for boycotts of Israeli universities, we could do worse than remember the challenges faced by the Jan Hus philosophers in their own fraught times. We should reject un-nuanced demands, while remaining alert to calls coming from inside the belly of the beast, made by those who are trying to change things from within.