By the year 1871, British officials stationed in India had learned to ride elephants. This was in fact exactly what Sir Henry Durand, Lieutenant Governor of Punjab, was doing when he fell to his death. In the sad record of the event, Sir Henry is described riding in a howdah atop an elephant while traveling through the North-West Frontier Province, ‘which was in his charge’. The elephant, which belonged to an Indian chief, was led through a covered gateway that was ‘too low for it to pass through’. As a result, Durand the younger writes: ‘My father, a man of great height, was forced backward and thrown out across a low wall, which so injured his spine that he died the same day.’

The unceremonious death of Durand the elder, the ‘man of great height’, can well be a study of the British in India at the time. They had quashed a mutiny in 1857, and conquered both the fertile province of Punjab and the southern province of Sindh. Yet they remained curiously vulnerable to surprises on the wild edge of the northwestern corner of their empire. Mortimer Durand, then in his 20s, would attempt to tame the frontier which had taken his father. It was Mortimer, and not the elephant-riding Sir Henry, who would be the architect, and namesake, of a border that remains a frontline for battles between superpowers to this day.

Durand the son arrived in India not long after his father’s death. He was searching not simply for accolades as a diplomat and colonial administrator, but also for a connection with his much adored but distant, and now late, father. Durand left his mark on the land, literally carving a border where there was none.

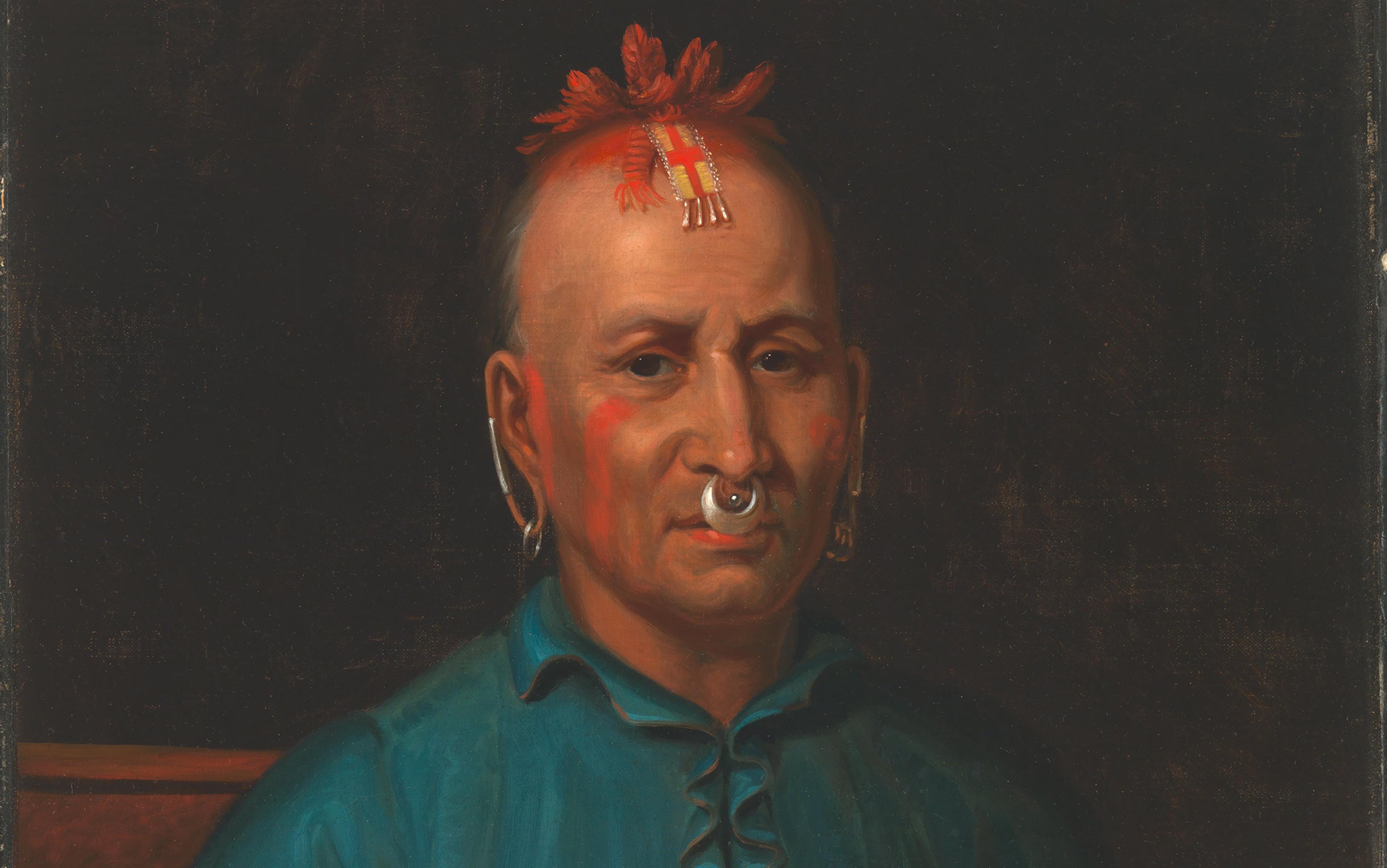

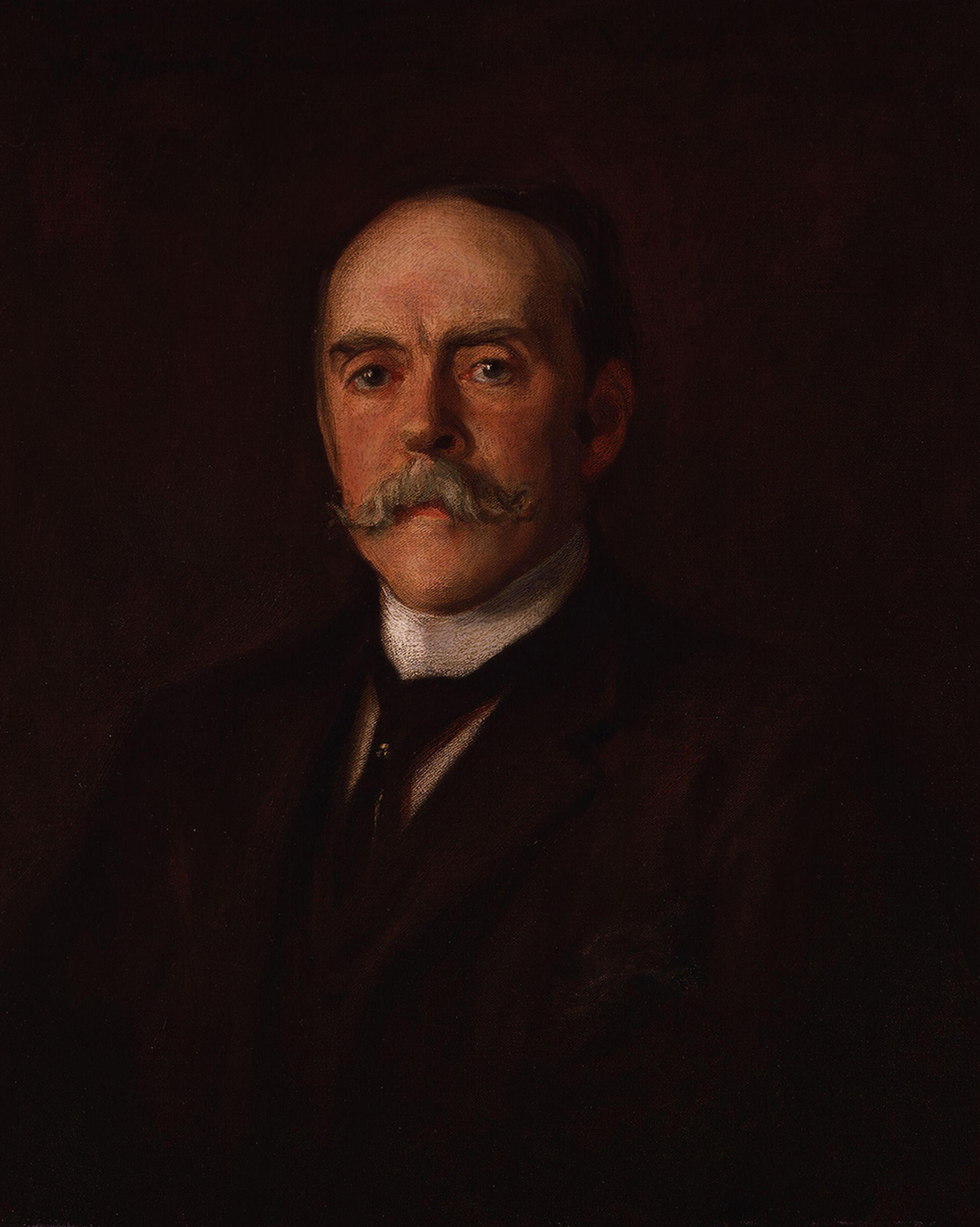

Sir Henry Mortimer Durand by W Thomas Smith. Wikipedia

His second quest, to connect with his father, proved more elusive. Percy Sykes, the author-diplomat who in 1925 wrote Durand’s biography, described Mortimer thus: ‘Of the service rendered to the State by Durand, the great maker of boundaries and thereby the great peacemaker, it is difficult to speak too highly. The Spectator which referred to him as “the strongest man in the Empire” did not praise him too highly.’ The encomium captured the heroic regard in which Durand was held by his compatriots. Such effusive praise does not come easy from the tight-lipped British.

Durand’s life had been a lonely one, long before he arrived in British India. He had a desolate childhood, in which he and his siblings were shunted from relative to guardian to boarding school. His father was stationed in faraway India, and his mother chose to go with her husband.

Indeed, Mortimer would lose his mother to India too. His diary recalls how he heard about her death. It was the late summer of 1857, and the children’s caretaker…

took my elder brother and myself up to a seat on the vine-clad hillside above the house, and told us of our mother’s death. She had been with my father when the revolt broke out in Central India, and after showing great courage, she had died in childbirth, worn out by exposure and fatigue.

Away at school in Switzerland, Durand never got the sympathies due to one whose parents were at the frontlines of the mutiny. Instead, the Swiss around him were quick to criticise the British as ‘oppressors of a nation rightly struggling to be free’. In his diary, he railed against the judgmental Swiss, who in his view have not the ‘slightest sympathies for the men and women cruelly murdered by the mutineers’.

If such were Durand’s feelings towards the erring Swiss, it is not hard to imagine that his feelings toward the mutineers themselves were of an even darker flavour. The British colonial administration shared Durand’s anger, and he would soon join them. In some sense, his arrival in India represented a sort of homecoming, politically. As the historian Victor Kiernan writes in The Lords of Human Kind (1969): ‘India was never forgiven for what it did in 1857, still less perhaps for what it exasperated the English into doing, or allowing to be done.’

Much British brutality followed the mutiny; the benevolent gloss over the British presence melted away by the open hostility and massacres that came with insurrection. Karl Marx, writing in 1857, quotes a young Englishman saying: ‘Every nigger we meet with we either string up or shoot.’ If the atrocities of Indian states under princely rule had been widely publicised as a pretext for British annexation, now the insurrection of the Indians became the justification of dominion and enforced subordination.

It is no surprise then that the post-mutiny India into which Durand arrived was one in which Britain took measures to clearly delineate the moral, social and racial division between coloniser and subject. But there were also class divisions between the British themselves. As a new arrival, Durand worried that he was not, as most senior civil service officers from pre-mutiny days were, a ‘Haileybury’ man. Haileybury was the training college in Hertfordshire once run by the now-disbanded East India Company, a place where Britain’s old aristocracy, displaced and useless following reforms in Britain itself, was trained and tutored to govern India.

His father’s demise left him with something to prove, both to the British and to the natives, whose insurrection had led to his mother’s death

Having sat for the civil service exams a little more than a decade after the mutiny, Durand saw himself instead as a ‘competition wallah [person]’ and different from the former who ‘were of a higher social class’ and therefore ‘suited to rule’. Durand’s admission is important. It reveals again how empire was rooted in the idea of British moral superiority; indeed, only the superior sort of British could be entrusted with the task of civilising the natives.

Though Durand lacked aristocratic lineage, his name was not unknown, thanks to his father. British propriety demanded that he be the beneficiary of the attentions and invitations of British India’s ruling elite, the lords and viceroys whose goodwill would determine the course of Durand’s career. He was a man who had risen on merit, but who also enjoyed the unnatural professional advantage of his father’s death. His father’s demise also left him with something to prove, both to the British and to the natives, whose insurrection had led to his mother’s death.

Durand rose to the challenge. After a few postings in Calcutta and Bhagalpur, where he served as magistrate, Durand’s mix of ambition and diligence was rewarded with promotions, and by June 1874 he was appointed Attaché to the Foreign Office. The primary work of the office was not the development and implementation of a foreign policy against foreign states (which was London’s domain) but rather the crucial mainstay of empire: negotiating relations with the many princely states and territories that fell under British control. Now a rising star, Durand married and had children, settling down beyond the Lines, the areas of Indian cities that were reserved for the ruling British.

In 1884, Durand was appointed to the Afghan Boundary Commission, whose work was a precursor to the demarcation of the Durand Line. The job was significant to him not simply for its strategic importance (Britain, worried about a Russian advance into Afghanistan, was eager to demarcate a boundary that would maintain the former as a buffer state between their own empire and the Russians) but also because the task was similar to what had preoccupied his father. Durand’s forays into tribal lands, ones that others in his position had been unwilling to make, brought him closer to the man he had idolised but who had had little time for him when he’d been alive.

In 1885, a year after the arrival of the Commission, the Russian and British representatives met at Zulfikar Pass, the Russians agreeing to the demarcation of a boundary so that they could insure their control of the headwaters of various canals. The meeting was important: two imperial powers brought together to sort out their interests. Now, if only the Emir of Afghanistan could be brought to the table, a resolution of the Afghan problem would be within sight. It was just what Durand accomplished a few months later. In April 1885, Afghan Emir Abdur-Rahman not only attended a banquet given by the Viceroy in Rawalpindi, he praised the friendship between the two countries. Lord Dufferin, then Viceroy, was so impressed that he immediately designated Durand as Foreign Secretary. Durand hence became the youngest foreign secretary in the history of the British empire, and the man who would demarcate the division of the empire’s tribal lands.

While the threat of Russian advances played a significant role in defining the necessity of a boundary between the British empire and Afghanistan, it was not the only reason. The British had failed time and again in their attempts to conquer Afghanistan, and they increasingly struggled to control the hill-based tribesmen of the frontier.

These men they saw as ‘absolute barbarians… avaricious, thievish and predatory to the last degree’, ‘mere vulgar, criminal and disreputable persons’. British policy was to try to ‘civilise’ and ‘pacify’ them even as they emphasised how the tribesmen’s traditions and poverty were obstacles in this regard. Taming the tribal areas, or at least part of them, was integral to illustrating and affirming the moral superiority of empire as well as highlighting its benevolence.

With these ideas as the context for his actions and ambitions, Durand travelled to the tribal frontier in late 1893. There, day after day, he doggedly sat with the Emir of Afghanistan, attempting to devise a border between the British empire and Afghanistan. One sticking point was Waziristan, the present-day stronghold of the Tehreek-e-Taliban, which both the Emir and the British wished to claim. When Durand asked the Emir why he wouldn’t give up Waziristan, which in his own words ‘had so little population and wealth’, the Emir responded with a single word: ‘honour’.

the British could now claim to have subdued and subjected – via cash, if not courage – the most visibly intractable portions of the tribal frontier

Honour gave way, however, to the cash that Durand was willing to offer. To reach agreement over the delineation of a northwestern border between Afghanistan and the British empire, the Emir’s subsidy was more than doubled from six lakh to 18 lakh rupees, and the promise of regular shipments of arms and munitions from the British government.

The result, as Andrew Roe writes in Waging War in Waziristan (2010), was ‘an arbitrary topographical line that stretched from North Gilgit to Koh-e-Malik Siah’ and that ‘divided the tribal areas uniformly between Afghanistan and British India’. According to Roe, the strategic, economic and political imperatives of the demarcation all pointed in different directions. However, the drawing of the line pointed to a greater victory, a moral one. In claiming half the tribal territory, the British could now claim to have subdued and subjected – via cash, if not courage – the most visibly intractable portions of the tribal frontier. In having bought off the Emir of Afghanistan, they also had their ‘buffer state’ against Russian expansionism.

On 12 November 1893, the agreement that was the basis of the Durand Line was signed. It was written in English, a language that the Emir himself could not understand. At the time, no chronological limit was stipulated, however its contents were re-affirmed by successive Afghan governments in 1905, 1919 and 1921.

The Durand Line, the frontier that Mortimer carved for the British empire, remains a live, unresolved problem. Pakistan claims the Durand Line constitutes the natural border; Afghanistan sees it as an illegitimate colonial imposition. Without question, it’s a porous, ineffective border. Moreover, it’s no coincidence that Durand’s imperial mapping project is today at the centre of the War on Terror. Americans might tend to think of the British empire in Asia as the distant past, but on the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, the Anglo-American empire feels like one continuous present reality.

In the imperial narrative of the making of the Durand line, much attention is paid to the British interests in curtailing the intractable tribal leaders. The line would, in this thinking, help control movement and make the tribes more governable. While instructive, this story neglects the moral dimension at the core of the British imperial enterprise in South Asia. Simply put, the delineation of the Durand Line must also be understood in relation to the larger colonial project of goading order out of chaos, and civilising and taming what the British believed to be the morally inferior population of the Indian subcontinent. As Kiernan noted: ‘a conviction was fixed in the British mind, unshakeable in later days’ that India without them would be ‘anarchy’.

What was the motivation of Durand and others of his class and background? Were they colonisers and empire-builders, or bureaucrats and governors? They were the men entrusted with the task of turning the principles of British presence in India into reality, and that included making physical borders. Their situation, both within English society and within the ranks of the colonial administration where their fortunes were made, is instructive. It’s not a ‘great man’ approach to history to acknowledge that power matters, and that these men with great power exerted influence that would last far beyond the ambit of their own lives. It does not mean that they always knew what they were doing.

The Durand Line is an example of one such ambiguous achievement that evolved out of the colonial order and whose current iterations continue to demand the attentions and resources of a neo-colonial enterprise. The Durand Line has consistently proven ineffective as the basis of territorial delineation between Afghanistan and Pakistan, its division of Pashtun tribal lands a point of contention to this day. As recently as May 2016, the portion of the line between Afghanistan and Pakistan at the Torkham checkpoint was shut down, stranding thousands of people and cargo trucks. Pakistani military forces installed barbed wire; Afghanistan, which does not recognise the legitimacy of the border, responded to this as a hostile act. Escalating tensions, well-known to either side, led to a shutdown of the Torkham border post. It was only after high level diplomatic meetings that the post could be opened again.

What the British worried over then is what the Americans are vexed by now: the frontier, the rough terrain, the seemingly inscrutable tribesmen

In sum, the Durand Line is one of those ongoing squabbles that show little promise for resolution. In June 2016, just after the Torkham crossing had been re-opened, the former Afghan President Hamid Karzai once again reiterated the Afghan position, saying in an interview to BBC Urdu that Afghanistan had not recognised the line since 1893 and that the ‘Durand Line is a blow-up that no Afghan can forget’.

In addition to the genealogy of conflict and the taint of artificial origins, the US presence in Afghanistan further complicates and magnifies the Durand Line’s failures. A few days before the Torkham shut-down, a US drone skirting the line between Afghanistan and the Pakistani province of Balochistan fired a missile at a car in which two people were killed, one of them Mullah Mohammad Mansour, the leader of the Afghan Taliban. The US, which recognises the Durand Line as the international border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, had chosen to ignore it. It argued that Pakistan’s inadequate policing of the border forced the US to violate Pakistani sovereignty, as well as permitting Taliban targets to hide and obtain refuge on its Pakistani side.

If the contusions and complexities appear damning, it is because they are. Excavating the genealogy of the Durand Line – how the concerns of colonial domination are reflected in its demarcations – might not provide solutions, but it does reveal the repetitive nature of the conundrums once faced by colonial powers and now by neo-imperial ones. What the British worried over then is what the Americans are vexed by now: the frontier, the rough terrain, the seemingly inscrutable tribesmen, all of this constituting the uncivilised border whose taming is somehow crucial to the colonisers’ own eminence.

Amid the details of negotiations and agreements, and the complications of competing interests, it’s easy to forget that the demarcation of borders was seen as a central instrument of colonial control. The emphasis on solidifying agreement over the Durand Line was important, not simply because it formulated a frontier but also because lines of control were integral to the British sense of the moral rightness of their colonial power in the first place. Therefore, demarcating new borders, effectively creating boundaries for nations that had not previously had them, stood as an affirmation of the precept of creating order out of chaos.

The contrast between marauding tribal disorder and stable colonial order was nowhere greater than on the Durand Line, an ominous pre-cursor of US dissatisfaction with its porous reality today. Per British strategic calculations then, establishing control over a portion of the frontier – albeit by creating a rentier state and profiting from topographical tribal enmities – illustrated the ability of empire to enact the moral virtues that were otherwise purported only in an abstract sense.

In this sense, the co-option of the ‘barbaric’ tribesmen presented a final frontier in the act of colonial domination. While the British had tried and failed to actually conquer the Afghan territories several decades before, this new solution not only reduced Afghanistan to a vassal state without having to mount a military campaign for its vanquishing, it also created a visible tribal frontier whose inhabitants, however intractable, were British subjects.

Like the British of old, the Americans today consider Afghanistan as a moral evil that must be fought in order to proclaim their global power

The moral optics of tribal societies offer contrasts to the modern and civilising missions of hegemonic powers and centralising states that continue today and could arguably even be considered the basis for continued preoccupation with the Durand Line. Pakistan, the inheritor of the British territories, wishes to retain control over the portion of the tribal areas on its side of the line but is unable to pay the rents or provide the munitions won by Afghan allegiance to the line under the British. Because of this, Afghanistan sees little value in acknowledging the frontier as legitimate. The role played by the British more than 100 years ago has arguably been taken over by the US, which now sees Afghanistan as its own buffer against expanding Russian and Chinese interests in the region.

Like the British of old, the Americans today also consider the tribal wilds of Afghanistan as a moral evil that must be fought, controlled and ultimately civilised in order to proclaim their global power. That’s why the Durand Line represents not only a strategic but also a moral frontier, whose colonisation is crucial, in its latest iteration, in the War on Terror.