The Sicilian mafia is probably the most famous criminal organisation in the world. It’s been known to exist at least since the 1870s, when a Sicilian landlord documented how a local group of mafia members threatened and harassed his business to the point that he had to escape from the island. Over the years, the Cosa Nostra and its North American offshoots have been depicted in numerous books, movies and works of popular culture. Yet the origins of the mafia have been regarded as something of a mystery. What factors explained its sudden appearance in Sicily after Italy’s unification in 1860-61? Were the mafiosi truly ‘men of honour’, as they called themselves, protecting poor, ordinary citizens from an oppressive state – or did their activity arise as a bulwark against communism?

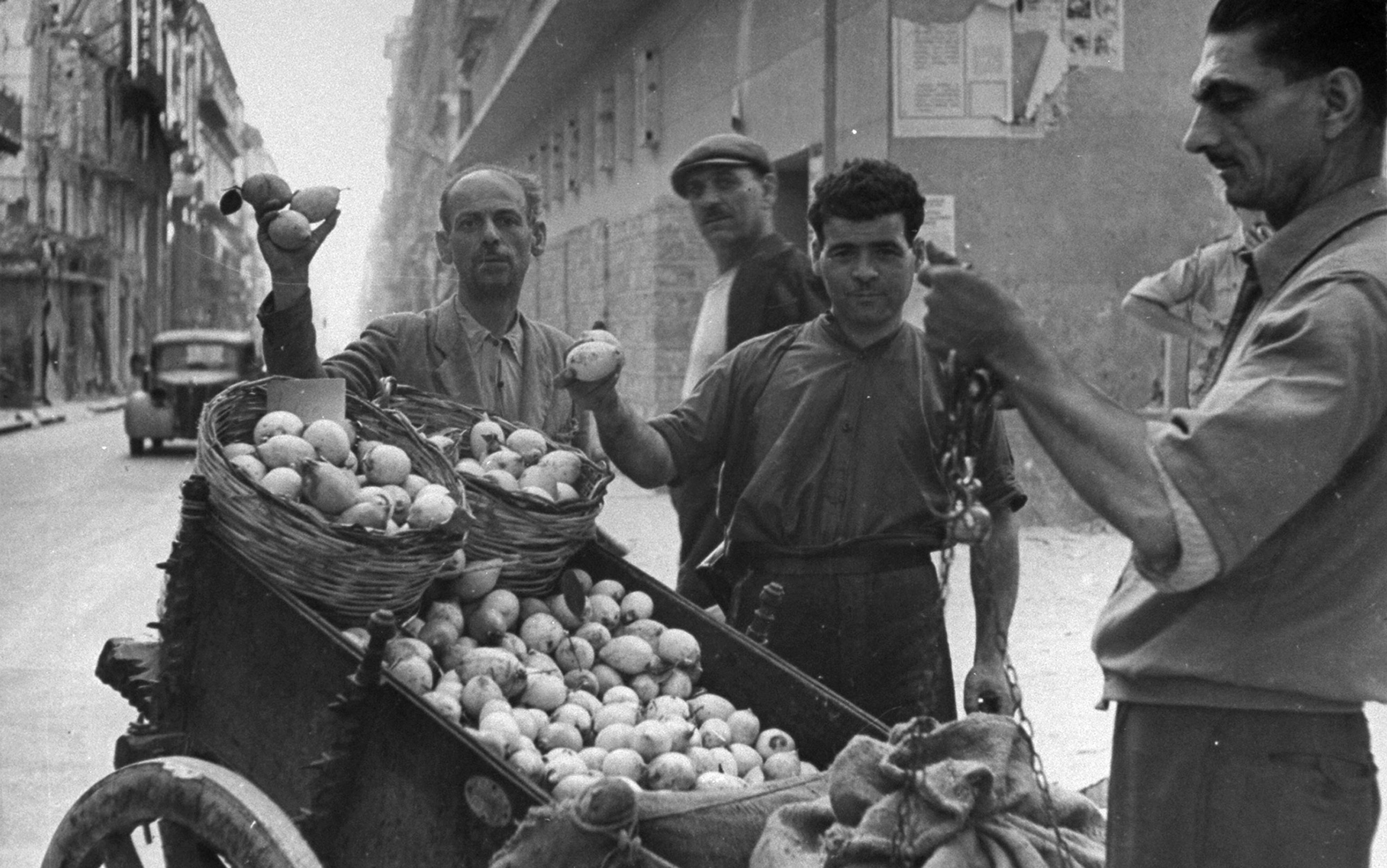

Recently, the economists Arcangelo Dimico, Alessia Isopi and I showed that a major catalyst for the rise of the mafia in Sicily was, somewhat surprisingly, the surge in demand for lemons and oranges that began in the first half of the 19th century. But to understand how fruit cultivation could lead to organised crime, we need to go back even further, to the conditions prevailing in the British Royal Navy in the 18th century.

Before 1800, sailors on long-distance voyages throughout the world were plagued by scurvy, a disease caused by vitamin C deficiency. Early symptoms included malaise and fatigue, while the more advanced stages of the illness might involve loosening or losing teeth, emotional turbulence, fever and convulsions. The death rate on long-distance voyages was typically high.

At the time, nobody had systematic knowledge of what causes scurvy, although they had derived sporadic insights. Then, in the mid-1700s, James Lind, a Scottish physician in the Royal Navy, conducted the first ever clinical trials on sick sailors. A control group was given the usual food served on ships, while a small group was fed portions of fresh fruit as treatment. Unsurprisingly (to us), this second group got better, and Lind published his findings in A Treatise of the Scurvy (1753). However, the research was largely ignored until the 1790s, when the Sick and Hurt Commissioners of the Royal Navy began recommending that lemon juice be regularly served to the whole fleet.

As knowledge of the beneficial effects of citrus spread through Europe, lemons became an increasingly precious commodity. The island of Sicily off the ‘toe’ of Italy was one of the few regions in the world that could meet the fresh demand. Lemons and other citrus fruits had been introduced to Sicily by the Arabs in the 10th century, who saw the opportunity afforded by the island’s hot coastal plains and exceptionally fertile soil. However, due to their sensitivity to frosts, lemons could be grown only in certain locations, slightly above the coastline. Prior to the early 19th century, lemons were mainly used for decoration and perfumes; Sicily’s main export goods at the time were wine, olives and wheat.

The recommendations of the Sick and Hurt Commissioners in Britain changed all this. In the coming decades, a great share of Sicilian agricultural production was redirected towards producing citrus fruits for the international market. However, the shift to large-scale lemon cultivation was not quick or easy. Only certain areas of the island were suitable, and even those required a lot of money to get going.

Once the seeds were sown, the young trees had to be pruned, fertilised and watered. The lemon farmers typically used horse-powered mills to water the plants at least once a week. In order to protect the trees from thieves and harmful winds, the groves were often shielded by high walls and fences. Unprotected groves with ripe lemons were otherwise an easy target for burglars or brigands. Several years of investment could easily be destroyed by marauders, or stolen during a single dark night. So in the mid-1800s, when export revenues started to soar, the groves were typically protected by armed guards.

Between 1837-50, the number of lemon barrels exported from the Sicilian harbour of Messina increased from 740 to 20,707. By the late 1800s, exports had grown dramatically. According to the British historian John Dickie’s book Cosa Nostra (2005), 2.5 million cases (each containing more than 300 pieces of Italian citrus fruit) arrived every year in New York during in the 1880s, most of them shipped from the Sicilian port city of Palermo.

The boom in demand for citrus generated huge profits for the lemon cultivators of Sicily. But just who were these farmers and what sorts of conditions were they working in?

Sicily in the early first half of the 19th century was characterised by fragile public institutions and a weak rule of law. Bandits roamed the countryside, and theft and poverty plagued the population. The roots of these problems ran deep. The island’s strategic location in the middle of the Mediterranean made it an obvious target for numerous foreign empires throughout history: after being dominated by the Ancient Greeks and then the Romans, Sicily fell under the control of Byzantine, Arab, Norman, Spanish and French rulers. Then, after the Napoleonic wars at the start of the 1800s, Sicily was ruled by Bourbon kings based in Naples, forming what was known as the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (1816-60). At this time, Sicily was generally a poor and underdeveloped region, and social unrest was common. Feudal structures remained despite attempts at reform, and major rebellions were suppressed by the Bourbon government in 1820 and 1848.

Between 1860-61, Sicily was conquered by troops from the mainland and became part of the newly formed Kingdom of Italy. The de facto capital was in Piedmont, to the far north. It soon became clear that many Sicilians were unhappy about the new arrangement. The intruders from the peninsula spoke a dialect of Italian that Sicilians struggled to understand and, in the eyes of many islanders, the Piedmontese state was just another foreign power trying to impose its will on the underdeveloped island.

It was in this post-unification environment, with its toxic mix of weak government institutions and large inflows of cash from the lemon industry, that the organisation known as the mafia first appeared. The word mafioso derives from Arabic, meaning ‘swindler’ or ‘cheater’. But in Sicily, the label didn’t have negative connotations. Rather, it suggested someone who deserved respect because he stood up for the local population against the lawless brigands and militias who roamed the countryside and threatened farmers.

The mafia placed its own people as wardens of groves, who appropriated parts of the harvest directly

Landowners began engaging local groups of such strongmen to protect the valuable lemon groves. At the same time, this ‘protection’ sometimes took on the character of extortion, and was more or less forced upon citrus growers. The first recorded example of such ‘unwanted’ protection comes from 1872, concerning a certain Dr Galati, a landlord who owned a lemon grove outside Palermo. Soon after he had acquired the grove, Galati learned that its warden had stolen fruit off the trees and taken a big portion of the sale price of lemon harvests for himself. Galati fired the warden and hired a replacement but, not long after this event, the new caretaker of the grove was shot. The police investigation proved inefficient. Soon, threatening letters began to arrive, demanding that Galati reinstall the previous warden. His refusal was followed by a series of assassination attempts, and eventually the doctor fled.

The Galati incident shows how groups of local ‘men of honour’, referred to as cosca, had managed to infiltrate not only the local villages, but also the police, politics and eventually the various markets that surrounded and supported the citrus industry. The coscas were secret groups whose members swore an oath of silence about the organisation and its activities, and soon controlled important parts of the supply chain for lemons. The mafia often tried to place its own people as wardens of groves, which allowed them to appropriate parts of the harvest directly. They could then develop monopolies and hike prices for buyers, and sometimes even act as intermediaries between producers and exporters in Palermo and Messina. Despite the drawbacks, in the chaotic environment of Sicily at the time, the local mafiosi were often preferred to the representatives of the oppressive Italian state. Given the large revenues from the citrus trade, there was still money to share around among both landowners and the mafia.

However, the newly minted Italian state soon identified the mafia as a problem. In 1877, the Italian parliament approved an extensive inquiry into the conditions of the agricultural sectors in the country, a key part of which concerned Sicily. An MP from Sicily, Abele Damiani, was made responsible for the local investigation, which was carried out during 1881-86. The inquiry sent a survey to all local pretori (lower court judges) in Sicily. Among other things, they asked: ‘What is the most common form of crime in the district? What are their causes? What are the most important crops or plants?’ The mafia came up again and again as the most serious problem in town.

We used this information to investigate whether there is a robust statistical relationship between the presence of the mafia and the cultivation of citrus, while also controlling for other factors such as the extent of cultivation of other crops, population density, and the extent that land was collectively owned by multiple parties. Our analysis shows that the prevalence of citrus-growing is generally a strong determinant of the existence of local mafia groups in the 1880s. The correlation remains even when we use a later inquiry from 1900, and when we use a measure of land’s suitability for citrus cultivation to complement actual observed citrus production.

Other scholars – including Dickie and the Italian historian Salvatore Lupo – have noticed that organised crime in Sicily arose alongside the demand for lemons. Previous studies have demonstrated that the mining of sulphur also played a role; others have argued that the drought of 1893 led to the rise of socialist fasci (‘league’) organisations, against which local landowners hired the mafia to protect them. Nonetheless, our empirical analysis supports the hypothesis that the market for citrus fruits was a major factor behind the rise and consolidation of the Sicilian mafia.

At the end of the 1900s, the Sicilian economy was hit by economic stagnation. The lemon industry faced severe competition from new citrus groves in Florida. As a result, tens of thousands of poor Sicilians emigrated to the United States, escaping chaotic conditions back home.

This wave of emigration brought not only Sicilians but the mafia to the US, too. Mafia groups were soon established in poor Italian neighbourhoods in New York City, and spread to other cities such as Boston and Chicago. The Sicilian mafiosi blended with southern Italians and criminal groups from other ethnicities to form the special variant of the American mafia. Meanwhile, in Italy, the Sicilian mafia, along with the Camorra in Naples and the ’Ndrangheta in Calabria, remained a major threat to the rule of law, up until the present day.

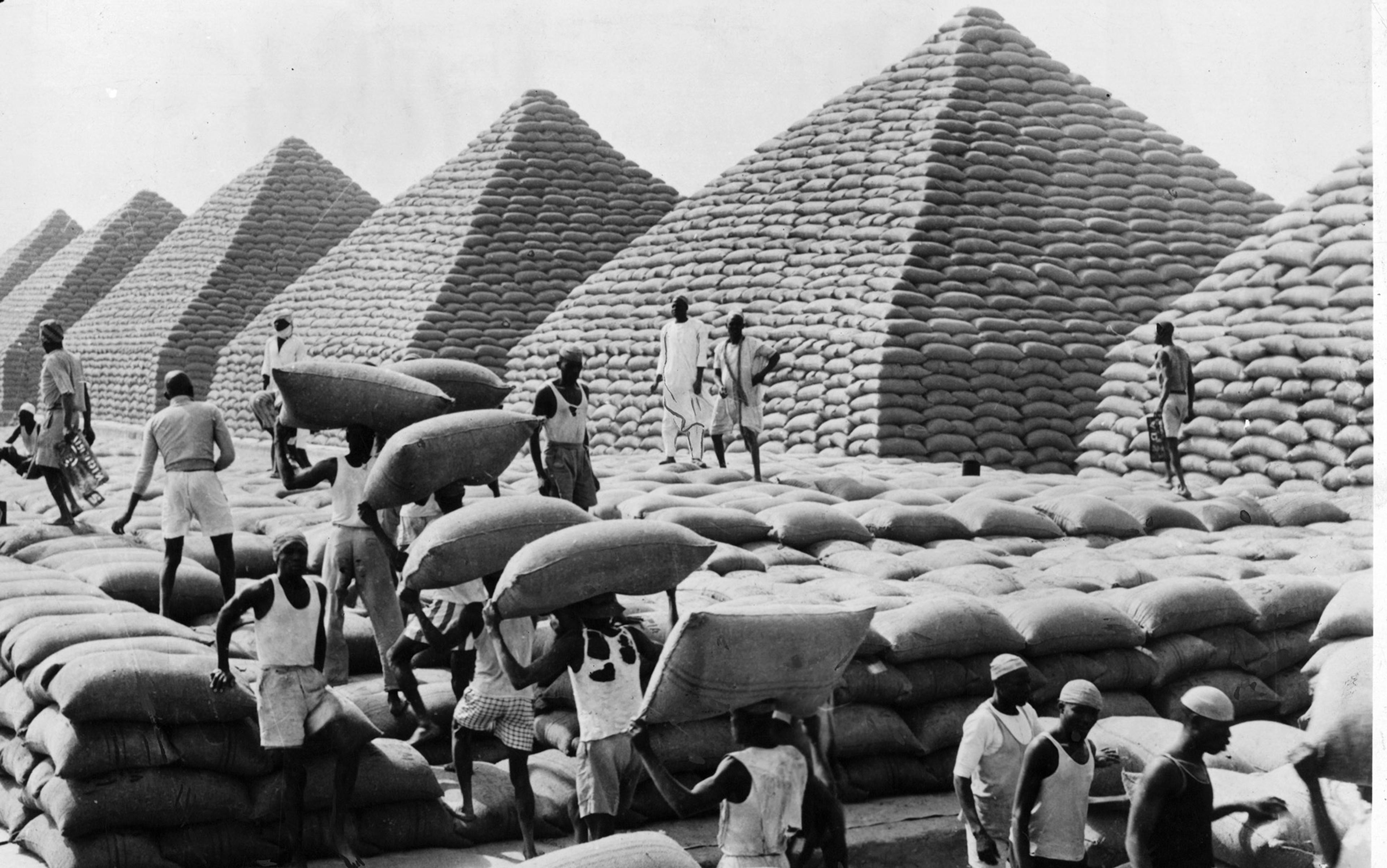

Is this story of criminal gangs that arose from poor governance combined with the exploitation of natural resources unique to Sicily? Not at all. In fact, economists and political scientists have coined the term ‘the resources curse’, to describe the frequently perverse effects of high profits from resources in underdeveloped regions of the world.

The most blatant contemporary example is so-called ‘conflict diamonds’. About a decade ago, the illicit trade in diamonds in countries such as Angola, Sierra Leone and Liberia led to the emergence of local strongmen who could control revenues from the trade. Eventually, they formed private rebel armies, with the primary aim of extracting profits from exporting to unscrupulous buyers with connections to Western countries. Like the mafia in Sicily, the rebel groups controlled both the production and trading networks, and used physical violence to force local populations to comply. Eventually, a UN-sanctioned policy framework was put in place (the Kimberley Process) that managed to curb the illegal trade. Part of the reason the wars in Sierra Leone, Liberia and Angola came to an end was that diamond profits could no longer finance the countries’ warlords. However, in eastern Congo, many rebel groups are unfortunately still financed by illegal exports of other ‘conflict minerals’, such as coltan, an essential component in mobile phones and other electronic appliances.

The story of the rise of the mafia in 19th-century Sicily reveals how mixing valuable resources and weak institutions produces a volatile cocktail. It’s one that can cause decades of suffering and poverty for local populations. Even the demand for seemingly harmless goods such as lemons can easily lead to the emergence of dangerous groups and criminal gangs. Although the Sicilian mafia no longer seem to be entangled with citrus cultivation, you are probably carrying a trace of other mafia-like organisations – embedded in your jewellery, or within your phone.