Every day when I open my eyes, my vision bobs between my bedroom and the horizon of sheets that have crept up the bed in the night. As a result of secondary breast cancer, I am paralysed from the waist down, and can’t drag myself up in the bed, so I remain slumped, inside and outside the day. When I use the remote control on my hospital bed to sit my back up, I slide down in the bed and my paralysed feet press against the bed end. I can’t trust myself to fix it, so I remain half under the sheets, waiting for my husband, mother or carers to come and release me.

Secondary breast cancer is the bad one – the one you die of. The public picture of breast cancer is the primary version – the one you can possibly be cured of, if you’re willing to go through a mastectomy, radiation and chemotherapy. The public picture of breast cancer suggests that women who have been subjected to this ‘slash, burn, poison’ model of treatment should consider themselves survivors. Yet breast cancer can come back as Stage 4 at any time in a woman’s life, and secondary breast cancer (SBC) is incurable. Depending on the type of breast cancer – there are at least four subtypes – a secondary breast-cancer patient is on chemotherapy, immunotherapy or hormone therapy for the rest of their shortened lives, and treatment is life-altering for almost all SBC patients.

I’m one of the unlucky ones. In January 2022, I woke up one morning and couldn’t lift my leg. We got me into hospital, dragging my right leg like a reluctant schoolchild, and soon discovered I had spinal tumours, in an uncommon location inside the spinal cord. A few days later, I lost feeling in my left leg, which turned out to be from a separate spinal tumour. I had radiation treatment which I was told could stabilise the tumour. But the nerve damage on my spinal cord was unlikely to improve, and I was told I’d probably never walk again.

Not being able to walk means a complete loss of independence. It dashes any hope I’ve had for a period of respite in which I might travel, go to work, or even meet with friends. It’s forced me to accept that I will, almost definitely, not see my home country, Australia, ever again. I’ve spent most of the past decade travelling abroad and far away from the Antipodes, and it was this adventurous life that I thought I’d miss the most. But it turns out to be the severing of my ties to home, to the spare sound of the morning magpie and the smoky smell of fallen eucalyptus, that feels physically unbearable.

They don’t tell you about permanent paralysis at SBC Breast Cancer camp, where the emphasis is often on ‘thriving’ with a terminal disease. They don’t tell you about liver failure or lung disease, which can make the last months of many patients’ lives almost unbearable. Then again, SBC is sneaky and has the ability to shape-shift and emerge malevolently in unexpected places. Aside from paralysis, I have a tumour in my left eye that has caused a retinal tear that makes it hard to see. Women I know have bladder tumours, bowel tumours, and all manner of bony tumours that affect their mobility. And then there is each SBC patient’s greatest fear: brain metastases, which can cause neurological symptoms such as seizures, palsy, and sensory alterations.

All of this exposes the lie of efforts by mainstream charities to glamorise breast cancer – to celebrate ‘survivors’ with a barrage of pink merchandise, pink-themed events, and pink-ribbon fundraising. It’s a vehicle for the promotion of heteronormative femininity, one that’s largely about being pleasing, attractive and sexualised for the benefit of others. I find little common ground here with the visceral reality of what I am going through. As a person with cancer, I often feel stripped of the layers of other identities that I have casually worn for years. Now I am swaddled with other labels – a patient, a woman, a victim, a survivor.

Yet keeping me company on this hard road are a group of feminist theorists who suffered through, thought with, and eventually died from breast cancer. Both Audre Lorde and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick exposed cancer as something fundamentally discursive, dominated by the usual discriminatory and exclusive categories of gender and race. They have guided me through some of the unexpectedly radical, gender-fluid and contradictory dimensions of living with breast cancer. On the one hand it’s all ‘pink positivity’; yet, on the other, it can involve years of interventions that cause havoc with our hormones, make us lose our breasts and hair, and otherwise disrupt many of the conventional markers of gender. These two opposing pressures – to perform an extreme kind of femininity and to be forced to trouble it in my own body – have been a crucial aspect of my own experience. While I might feel powerless in the face of how this disease is undoing me, Lorde and Sedgwick have granted me a measure of solace – a sense of power, and a means to resist the political endowments of my condition.

The pink ribbon itself is most closely associated with the Susan G Komen foundation – the largest breast cancer awareness charity in the United States, which hosts the Susan G Komen Race for the Cure every year. Founded in 1982 and named for the founder’s sister who died of SBC, the organisation very quickly became the most powerful in the breast cancer community. It spearheads the pink-ribbon campaigns of October, the designated ‘Breast Cancer Awareness Month’, hosts large charity galas, and has more than 200 corporate sponsors.

Komen was not the origin of the breast cancer movement; that was arguably in the ‘women’s health’ movement of the 1970s, a branch of feminist activism that sought to fight the medical establishment’s disregard for women’s health issues (the most famous output of this is the book Our Bodies, Ourselves, first published by the Boston Woman’s Health Collective in 1970). The women’s health movement was far more radical than Komen and its offshoots. Rather than focus on positive survivorship, it emphasised how the medical profession ignored women and, especially, failed to strive for a cure or less interventionist and traumatic treatments. The emergence of charities such as Komen, the Estée Lauder Breast Cancer Campaign, or the Ralph Lauren Pink Pony campaign arguably represent not only the corporatisation but also the feminisation of the breast cancer movement. As Barbara Ehrenreich has written in Smile or Die (2009), her memoir and critique of breast cancer discourse: ‘Everyone agrees that breast cancer is a chance for creative self-transformation – a makeover opportunity, in fact.’

Transmen are increasingly presenting at doctors’ surgeries with lumps that need to be investigated

The way the mainstream breast cancer movement has aestheticised the disease goes hand in hand with social pressure to perform heteronormative womanhood. Nowhere is this more evident than in the charity Look Good Feel Better: founded in the late 1980s, it offers women with breast cancer a free makeover (with products donated by cosmetics companies) which includes a class to teach them how to make up their chemo-ravaged faces. In other charitable efforts, pink glitter is sprinkled on cars, on yogurt pots, on bras, T-shirts and scarves. Conventionally attractive models and celebrities wear Ralph Lauren’s Pink Pony sweatshirts and sometimes even strip down to their underwear to encourage women to ‘check your boobs’ for lumps. Companies investing in pink-ribbon culture are rarely transparent about where their money goes, because it would reveal how little of it goes to research as opposed to endless awareness campaigns. For example, Yoplait, which ran a pink-ribbon campaign each October from 1998 to 2016, donated just 10 cents for each pink lid that consumers mailed back to the company. As the medical writer Gayle Sulik despairs in Pink Ribbon Blues (2011): ‘billions of dollars are siphoned into branding efforts instead of the prevention and eradication of disease.’ Komen currently donates less than 20 per cent of the money it raises to research, and a large proportion is poured back into costs related to fundraising, thus existing to perpetuate itself.

This pink positivity is clearly highly gendered, focusing almost exclusively on those who identify as women. This is despite the fact that a small number of men get breast cancer, while transmen are increasingly presenting at doctors’ surgeries with lumps that need to be investigated. Indeed, breast cancer, and the experience of treatment, opens up an array of potential genderqueer identities. One might even argue that the heart of pink-ribbon culture is the demand to perform upbeat, cheerful and attractive femininity, even when shorn of one’s breasts, precisely so as to close off the genderqueer possibilities it otherwise raises.

Even the emphasis on ‘checking your breasts’ exposes the bias of pink-ribbon cancer culture. It is an important, albeit scientifically controversial, message; it can also distract from awareness of other symptoms in other, less overtly ‘female’ parts of the body, especially of Stage 4 breast cancer. The first symptom of my own cancer was redness – not a lump – on the skin of my breast. This was 2019 and I was 35 years old. The following year, I started having chest pains, though they disappeared and it’s not clear if they were related to the cancer. But a later scan revealed a mass on my lungs, which turned out to be metastases.

Within the breast cancer patient community, there is considerable discussion of femininity, womanhood and its loss. I messaged and spoke to some fellow members of METUPUK, the breast cancer advocacy group I belong to, about how their treatment did or did not relate to any sense of femininity. Meg was one of the first to respond (all names have been changed out of respect for correspondents’ anonymity) and her WhatsApp reply was one of the starkest: ‘Being bald I felt like an “it” (with) no gender.’ Seeing their female identity through the prism of their appearance was a common theme; baldness was frequently raised as a source of grief, as was anything to do with breast surgery. ‘I had my mastectomy in 2016 and still not had my reconstruction,’ Anna wrote to me, ‘it made me less than a woman, having a flat side and not being able to wear a T-shirt or even a V-neck dress … without putting in a softy [prosthetic]!’

It’s notable that Anna said she became ‘less than a woman’ – not just that she felt less like one. For many women, our treatment chips away at the gender identity we have carefully built up over the course of our lives. Most women have to take hormones for years after primary treatment, and potentially indefinitely if they have hormone-positive Stage 4 breast cancer. This often involves a deliberate shutdown of the ovaries by monthly injections of either Zoladex (a luteinising hormone blocker) or Lupron (a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist), which can mimic menopause in premenopausal women; an aromatase inhibitor, which further lowers the oestrogen levels in postmenopausal women; and for Stage 4 women, new classes of blockers such as CDK4/6 inhibitors (which target not hormones but proteins in breast cancer cells) and selective oestrogen receptor degraders (SERDs). This melange of treatments essentially works to make oestrogen levels as low as possible so as not to feed hormone-dependent cancers. Given that around 70 per cent of breast cancers are hormone dependent, that is a large number of women grappling with the physical and psychological effects of profoundly altered hormones.

One consequence is a change in libido and the physical ability to have sex. Meg wrote to me about her vagina becoming ‘the Gobi desert’, and some of us swapped tips for oestrogen-free lubricants in our WhatsApp group. Cheryl said: ‘I fell out of love with sex after the primary diagnosis … I feel absolutely nothing.’ Such feelings suggest a psychological as much as a physical change. A striking point was how many of the respondents assumed that I meant sex and intimacy when I asked about how breast cancer affected their gender identity. Femininity and sex are so closely intertwined in public culture that sexual intimacy is where many believe their identity is to be found, and damaged.

Pink femininity has to be so visible precisely because it is so unstable and weak

Yet this brings with it certain genderqueer possibilities. Molly observed that trans and other gender-nonconforming people get breast cancer too, yet they’re excluded from pink-ribbon culture. She had a friend assigned female at birth who was transitioning to male, but his mother wanted him to hold off on all hormone treatment until he was 21 because of a family history of breast cancer. However, it may be that some hormone treatments prescribed during transition could decrease breast cancer risk. Some of the laundry list of hormone treatments for breast cancer are the same as drugs taken during transition – most notably Lupron, which can be used as a puberty blocker in children as well as adults, and aromatase inhibitors, sometimes given for so-called ‘precocious puberty’. There is so little research done so far on transgender individuals and breast cancer; one hopes there will be more soon.

Molly found it hopeful, though, that the increased visibility of transmen and transwomen was encouraging more acceptance of fluid gender identities, and that genderqueer people were ever more welcome in grassroots breast cancer groups. Perhaps there are seeds of hope for a genuinely queerer breast cancer culture, which might see with greater clarity what a patriarchal medical establishment has elected to overlook.

Cracking open the association of breast cancer with biological womanhood can reveal other intersectional identities, especially the cross-pollination of gendered and racial selves. Sara, from METUPUK, wrote to me: ‘I’m from an ethnic community. That’s the worst thing, people from our community look at you and feel pity for you, [the] worst thing is going to an Asian wedding when you are diagnosed with cancer.’ The experience of breast cancer patients from Black, Asian and other marginalised groups is rarely present in media portrayals, and although groups like Black Women Rising exist to resist this marginalisation, in mainstream breast cancer culture, there is still only a token effort to change.

In this context, the frantic performance of pink femininity takes on a specific hue; it has to be so visible precisely because it is so unstable and weak. As the scholar Amy L Brandzel has written, the ‘anti-intersectionality’ of pink-ribbon culture serves to close off patients’ connections ‘to transgender embodiments, queered affects, disabled communities’. Breast cancer is a direct strike against stereotypic womanhood – with the hair loss that accompanies chemotherapy, the early menopause wrought by hormone treatments and, perhaps most of all, the mastectomies, which involve a physically and psychologically violent act. Faced with this attack on normative femininity, pink positivity allows women to feel they not only retain womanhood, but that it has been augmented. While these efforts are designed to show that women with breast cancer are still wives, mothers and lovers, the effort that’s put into foregrounding the ‘feminine’ in breast cancer charity and awareness could be read as a performance of a new femininity – a truer one than before.

An unusual number of late-20th-century feminist thinkers suffered and died from breast cancer. Perhaps the most famous is Lorde, the poet whose book The Cancer Journals (1980) still dis/comforts women living with the disease. A slim volume, it is searingly honest about the violence breast cancer does to the various veils that we otherwise hide behind: gendered, but also racialised, sexualised identities. She writes:

For months now I have been wanting to write a piece of meaning words on cancer as it affects my life and my consciousness as a woman, a Black lesbian feminist mother lover poet all I am [emphasis mine].

A lot of meaning lies nested in those three words ‘all I am’: they reveal the extent to which Lorde wrapped herself in both marginalised and generalised identities – a Black lesbian but also a lover and a poet. All these identities suffered from the invasion of cancer into her life and her consciousness, but by listing ‘Black lesbian feminist’ first, Lorde emphasises how at odds with the breast cancer experience they are.

Lorde’s reflections on the disorienting effect of cancer may seem untethered from the physical sides of treatment. But her other writings put the violence of surgery front and centre, when she laments how the act of mastectomy untethers her from her femininity:

I believe that socially sanctioned prosthesis is merely another way of keeping women with breast cancer silent and separate from each other.

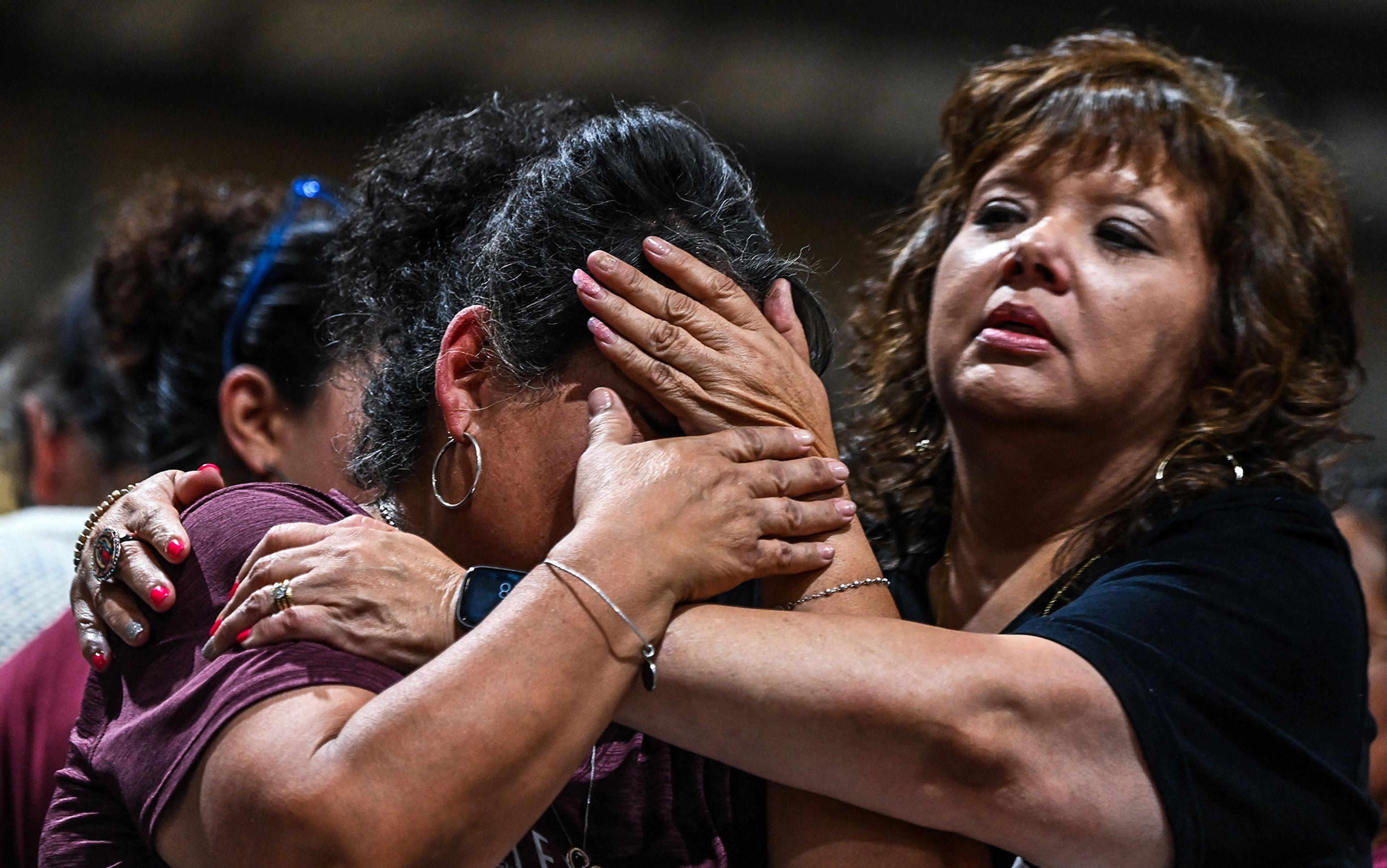

Lorde imagines an army of one-breasted Amazons marching to Congress and protesting the use of carcinogenic agents. She believed that environmental degradation was partially responsible for her cancer, beliefs that linked her to the feminist environmental movement of the 1970s. Lorde is critical of breast cancer ‘positivity’, but her passages against mastectomy chime with other activists who tie the loss of a breast to a loss of female-ness. She reifies the relationship between the woman and the breast, and cries loudly against the attempt to break that relationship. The healing she experiences afterwards is wrapped up in her sense of womanhood. She describes the group of women in her life, including her partner, who rushed to help her when she was recovering from the mastectomy: ‘Perhaps I can say this all more simply; I say the love of women healed me.’ Sisterhood and solidarity are central to Lorde’s understanding of womanhood, and her recovery more specifically.

Sedgwick gives us a way to think that’s quite different to the heteronormative, pink-ribbon platitudes

Lorde’s fear of the broken relationship between woman and breast is echoed in the writings of Sedgwick, the feminist and queer theory scholar who also lived with and eventually died from secondary breast cancer. Sedgwick is considered one of the founders of queer theory, and labelled her own experience of cancer ‘an adventure in applied deconstruction’. For her, queer theory’s emphasis on ambivalences, penumbrae, erasures and fracturing helped her probe her own psychological responses to the disease. ‘I have never felt less stability in my gender, age and racial identities,’ she wrote, calling her own process of treatment a ‘dizzying array of gender challenges and experiments’. Her response was in many ways typical – she mourned the violent interventions that produced the bald head, the lack of breasts, the missing eyelashes – but she also considered herself lucky to have the crutch of queer theory to see her through. As she wrote in Tendencies (1993), Sedgwick coped by ‘hurling my energies … to the very farthest of the loose ends where representation, identity, gender, sexuality, and the body can’t be made to line up neatly together.’

Her career-long infatuation with queerness (she was, herself, in a long heterosexual marriage, an irony that did not escape her) helped her in at least one other way. In the 1990s, the same decade in which she was diagnosed, it was hard to think of incurable illness without thinking of the AIDS epidemic. Breast cancer and AIDS activism had been linked before: the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) was the inspiration for groups such as Breast Cancer Action, founded in 1990. Breast Cancer Action refused to produce the depoliticised material that came out of mainstream groups like Komen, and focused instead on lobbying for more research and probing into the causes of breast cancer. This also linked certain corners of the breast cancer movement with the environmental movement, as activists focused on possible carcinogenic chemicals and pollutants.

Sedgwick’s involvement with ACT UP predated her cancer, and at the time she was diagnosed she was deeply involved in setting up a local chapter and providing emotional support for a distant, dying and dear friend with AIDS. After her diagnosis, she deepened her thinking about AIDS and the role of incurable illness in the fashioning of late-20th-century identities. She was interested, she later wrote, in the ‘dialectical epistemology of the two diseases, too – the kinds of secret each has constituted; the kinds of outness each has required and inspired – [this] has made an intimate motive for me.’

She understood herself to live at a point in history and in a way that forced an intimate association with early death: not only for those in a queer milieu, but also for urban women of colour, forced to the brink and beyond by poverty, violence and state indifference. When plagued with the inevitable ‘Why me?’ question, Sedgwick gives us a way to think about an answer that’s quite different to the heteronormative, pink-ribbon platitudes.

If a queerer, more radical form of breast cancer activism is to be inspired by ACT UP, it makes sense for it to focus on improving access to drugs and accelerating research into a cure. And any research into a cure has to start with the people actually dying of the disease – women with Stage 4 breast cancer – rather than focused purely on prevention. This is what the organisation I am involved with, METUPUK, seeks to do, and is joined in the US by the likes of Breast Cancer Action and METAvivor. All work to raise awareness of the plight of women dying of SBC and of raising funds for and promoting research into SBC – as opposed to primary cancer, which tends to have better outcomes and is therefore more lucrative. These SBC groups are vocal critics of the pinkwashing that happens in October and throughout the year, and seek to provide an alternative for people (be they woman, man or nonbinary) who are angry about the statistics and want to see change. This is the urgent, vital work that does indeed get me out of bed. It also inspires me as I try to recover from my spinal injuries. And something may be working – because, reader, I can wiggle my toes.

Philippa Hetherington died on 5 November 2022. Her family invite you to make a donation to METUPUK here.