The police report would have baffled the most grizzled detective. A famous writer murdered in a South Dakota restaurant full of diners; the murder weapon – a simple hug. A murderer with no motive, and one who seemed genuinely distraught at what he had done. You will not find this strange murder case in the crime pages of a local US newspaper, however, but in a Bulgarian science-fiction story from the early 1980s. The explanation thus also becomes more logical: the killer was a robot.

The genre was flourishing in small Bulgaria in the last two decades of socialism, and the country became the biggest producer of robotic laws per capita, supplementing Isaac Asimov’s famous three with two more canon rules – and 96 satirical ones. Writers such as Nikola Kesarovski (who wrote the above murder mystery) and Lyuben Dilov grappled with questions of the boundaries between man and machine, brain and computer. The anxieties of their literature in this period reflected a society preoccupied with technology and cybernetics, an unlikely bastion of the information society that arose on both sides of the Iron Curtain from the 1970s onwards.

One thing that the computer revolution brought was a certainty that industrial society was changing, or even about to be finished. As the American sociologist Daniel Bell put it in 1973, the new society was one where ‘what counts is not raw muscle power, or energy, but information’, where the new professionals would be producing immaterial goods. Information put a premium on knowledge and brainpower, as well as on human creativity. The new order was not just one that would change the economies of the advanced countries, but the very core of what it was to be a worker within it – and thus more broadly, a human within a world of thinking machines. The British sociologist Frank Webster put his finger on the change when he stated in 2004 that the output of the new man is ‘a change in image, relationship or perception’. This implied a change also in the self-image of man – no longer a manual worker, and now in symbiosis with his own thinking tools and digital screens.

The communist parties of eastern Europe grappled with this new question, too. The utopian social order they were promising from Berlin to Vladivostok rested on the claim that proletarian societies would use technology to its full potential, in the service of all working people. Bourgeois information society would alienate workers even more from their own labour, turning them into playthings of the ruling classes; but a socialist information society would free Man from drudgery, unleash his creative powers, and enable him to ‘hunt in the morning … and criticise after dinner’, as Karl Marx put it in 1845. However, socialist society and its intellectuals foresaw many of the anxieties that are still with us today. What would a man do in a world of no labour, and where thinking was done by machines?

Bulgaria was not such a strange place for these ideas to spawn lively debate. The Balkan state was, by the 1980s, the Eastern Bloc’s ‘Silicon Valley’, home to cutting-edge factories producing processors, hard discs, floppy drives and industrial robots. It was called ‘the Japan of the Balkans’, producing nearly half of all computing devices and peripherals in the Eastern Bloc. Kesarovski himself was a trained mathematician, who spent time working in the electronic industry. He was one of more than 200,000 people who produced electronics in a country of just over 8 million people, the second biggest group of industrial workers. The party trumpeted its achievements worldwide, proud of transforming a small agricultural and backward state to a vanguard of the information society in the space of a generation.

Back in 1944, as the Red Army rolled over the Danube, and the Bulgarian communists took power in Sofia, the country was mainly an agricultural producer, its tobacco calming German troops throughout occupied Europe. As the cigarettes switched to the pockets of Soviet troops and citizens, so did society switch from the land to the city, with millions streaming into newly built workers’ dormitories and factories. By the 1960s, Bulgaria had been thoroughly transformed by breakneck industrialisation. The shortcomings such as poor housing or insufficient city infrastructure were not glaring enough to take the gloss off the massive achievement that was socialist modernisation. A sense of optimism pervaded many in a society that was now producing machines, cars, ships. As the Party sought extra cash, it focused on electronics as the specialised good of the future, and a niche that was yet to be filled by any one communist country. Computers and electronics were being produced throughout the Eastern Bloc, but not a single country was truly mass-producing them, and the region lagged behind its capitalist competitors.

The Bulgarians surged ahead of their socialist allies through close contacts with Japanese firms and a massive industrial espionage effort. While Bulgarian engineers signed contracts with Fujitsu, state security agents criss-crossed the United States and Europe in search of the latest embargoed electronics to buy, copy or steal. In 1977, a whole IBM factory for magnetic discs based in Portugal was bought by a cover firm and shipped off to Bulgaria; elsewhere, secrets were passed on to Bulgarians by their foreign colleagues through the simple exchange of catalogues and information at conferences and fairs. Scientists back in Bulgaria reverse-engineered, improved, tinkered; soon towns that once processed tobacco were supplying hundreds of millions of customers with computers.

The socialist economy was beset by problems of product quality, and the leadership placed the blame squarely on the workers themselves

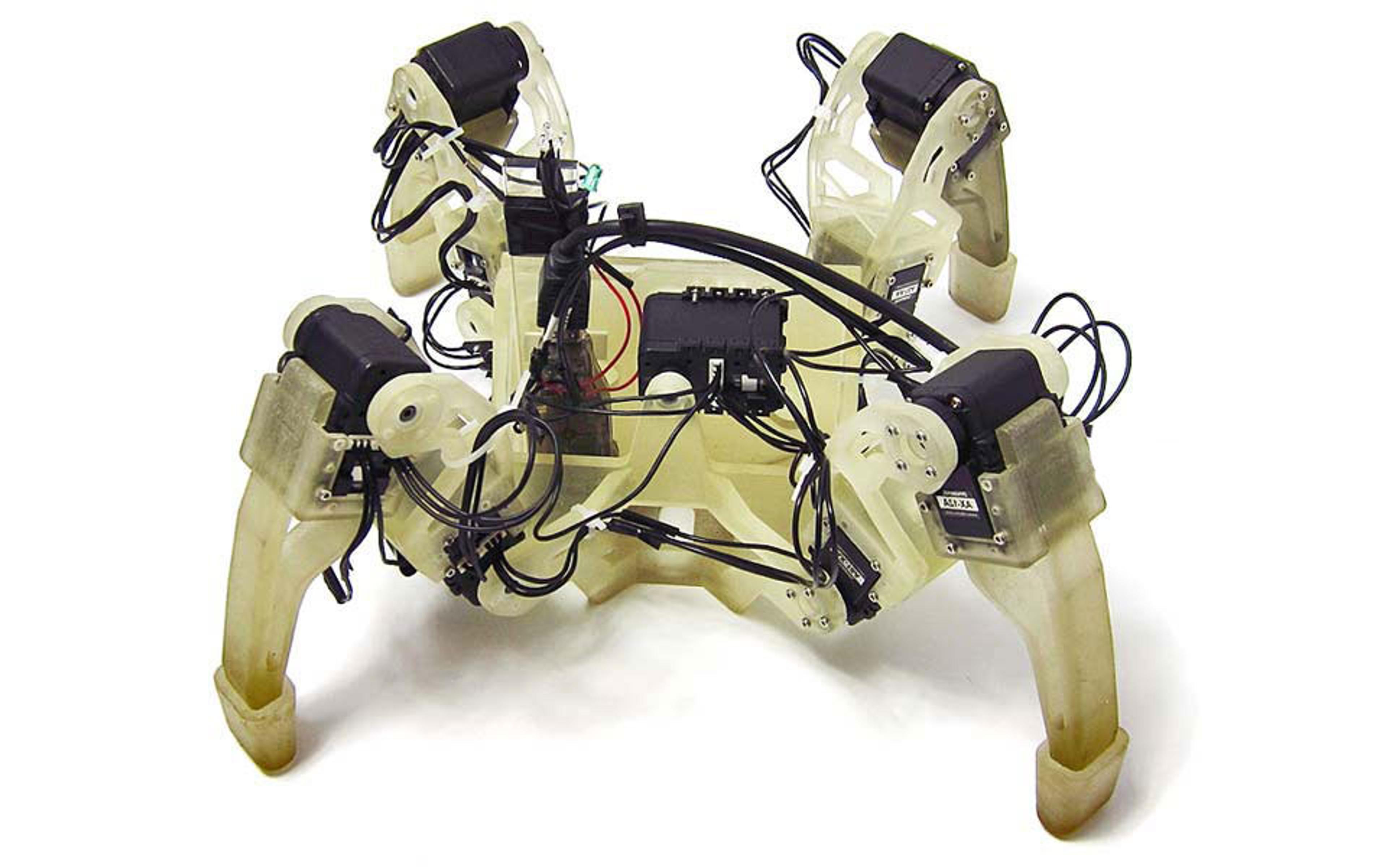

Some of these customers were in Bulgaria itself. Imperfect and piecemeal, automation nevertheless entered the shop floors of factories, warehouses, offices. As the country started producing robots and personal computers in the 1980s, more and more menial work was being done by steel muscles, and more and more offices and services became computerised. The party itself proclaimed confidently that it was through ‘cybernetisation’ that communism would be built. Computers in Bulgarian factories would provide accurate information about the economy, feeding information back to Sofia and allowing for accurate and perfect planning. The way to solve problems such as shortages or bad accounting and pilfering was to automate data-collection, decision-making, the whole administration of the economy. All this would be done through a vast computer network, which would cover Bulgaria and link even the smallest collective farm to the central computers in the capital. Similar plans had been dreamt up in other socialist countries, most notably the Soviet Union with its massive OGAS plan. Through perfect feedback, the plan went, Bulgarian socialism would function as a complete organism.

More so, the Party argued, as computers and robots took over from the fallible worker, quality would improve. The socialist economy was beset by problems of product quality, and the leadership placed the blame squarely on the workers themselves. ‘Robotisation will introduce changes in the role of the subjective factor in production quality. It will no longer be determined by the psycho-physical and physiological abilities of man, but by the stored programs and capabilities of the machines,’ thundered the Politburo, sure that Socialist Man was not cut out to be the perfect worker that a robot was.

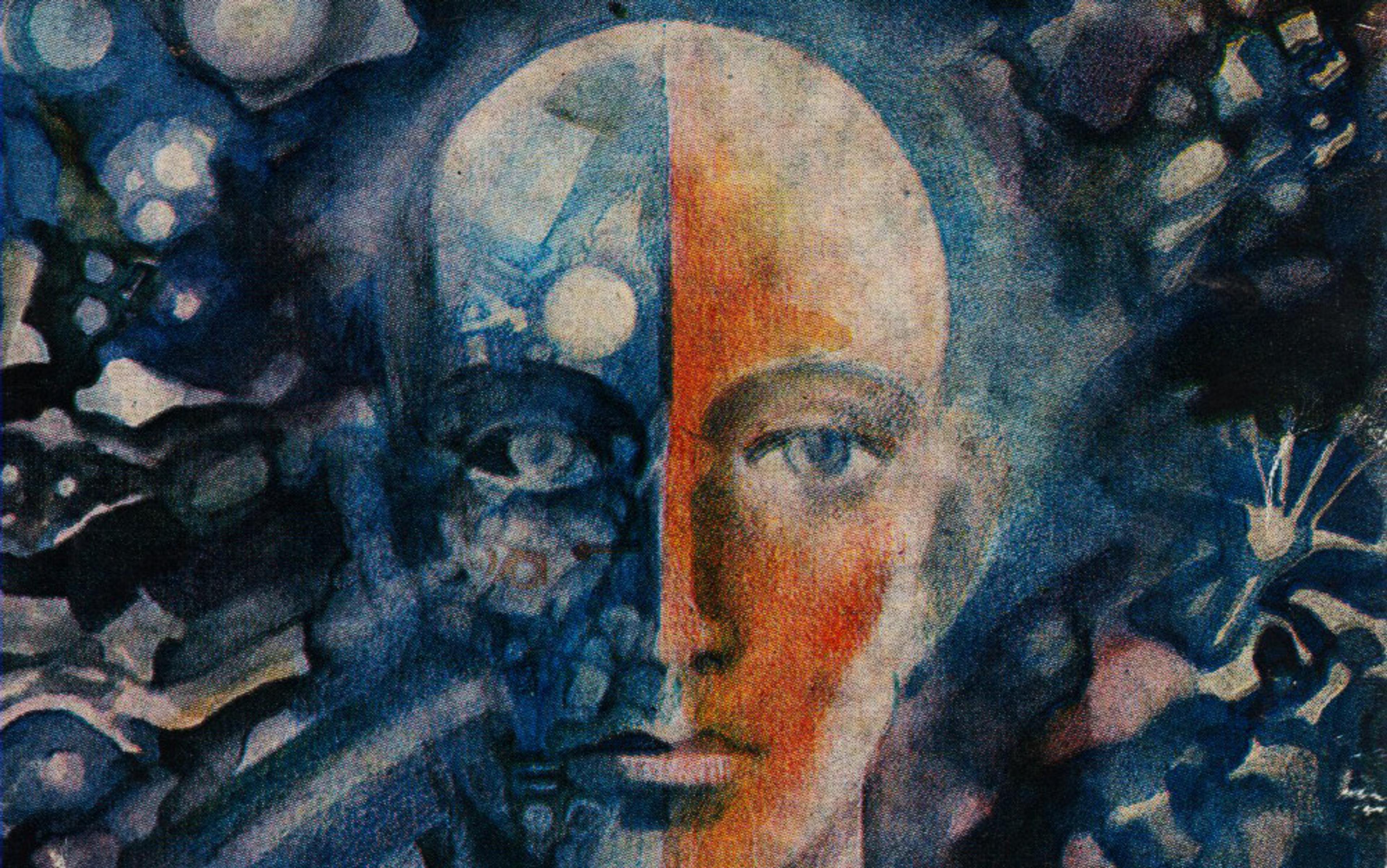

Bulgarian engineers and cyberneticians, champions of this new technology, increasingly worried about what this meant. In the ivory towers of places such as the Institute of Technical Cybernetics and Robotics in Sofia, they wrote detailed papers on robotic movement, image recognition, planning algorithms. They ran experiments and built labs to test how to perfect Man-Machine Interfaces – from the design of the perfect office that would minimise an office worker’s eye-strain to the future melding of human and machine vision. Increasingly, they saw humans as cyborgs – the socialist economy was melding them with machines they had to operate or even take orders from.

Tasked with creating such cyborgs and the theory behind them, many of these technical intellectuals started worrying about the effect on humans in general. Their debates moved out of the labs and onto the pages of the premier philosophy journal in the country, as well as popular-science magazines with names such as Cosmos and Orbit, aimed at teenagers and adults alike. The Bulgarian reader was increasingly treated to debates about what humanity would be in this new age. Some, such as the philosopher Mityu Yankov, argued that what set Man apart from the animals was his ability to change and shape nature. For thousands of years, he had done this through physical means and his own brawn. But the Industrial Revolution had started a change of Man’s own nature, which was culminating with the Information Revolution – humanity now was becoming not a worker but a ‘governor’, a master of nature, and the means of production were not machines or muscles, but the human brain.

Man would thus create rather than truly produce. Bulgarian engineers became caught up in the great cultural politics that swept the country in the late 1970s and early ’80s, under the auspices of Lyudmila Zhivkova, the culture minister and daughter of the country’s leader. Interested in theosophy, Eastern mysticism and Indian philosophy, she trumpeted the need for a New Man who would be multifaceted and truly creative, driven by the ideals of aesthetics and beauty.

Computers promised to help this by allowing this New Man to harness the information overload of the modern world, and use the accumulated centuries of human knowledge to shape himself into a new Renaissance man. The power unleashed by science would allow humanity to rise to a new height and assume great moral responsibility. The new Cybernetic Man, argued the philosopher Victor Stoytchev, should strive to be Salieri rather than Mozart. While the Austrian genius was one in a billion, a true freak of nature, his Italian nemesis had approached and rivalled him by a steadfast routine – he broke down big tasks into many small ones, and through labour and perseverance mastered the elements that make up musical genius such as counterpoint or harmonics. Salieri showed the way to true creativity rather than awaiting the gift of capricious nature. He was not a sad figure, Stoytchev says, but the carrier of the new form of art and perfection – perfection through labour, mastery through selecting the right information. He was the real, achievable genius that any Socialist Man could be, if he put his mind to it in this new age.

Such laudatory language showed an inherent optimism that was not in line with reality. As computers came to the workplace, psychologists pointed to the rise in anxieties among the workforce. These machines were not spurring creativity, but often stifling it. Directors used them to surveil their workers, who in turn feared that they would soon be obsolete. Physiological problems of strain were highlighted, as were psychological issues stretching from anxiety to addiction. Man was becoming dependent on the very machines that he feared and was oppressed by, while those who loved these new tools fell into dream worlds and lost a sense of reality, warned reports in the late 1980s. Bulgarian children had started taking compulsory computer classes as part of their schooling in 1984, and more and more politicians and engineers wondered about the effect. While this ‘second literacy’ was key to the new world, weren’t more and more children falling into this new addiction?

The children were also reading the outpouring of science-fiction stories that were concerned with the same questions. Dilov, one of the towering figures in Bulgarian science fiction, shot to prominence with his novel The Road of Icarus (1974). Humanity has taken to the stars on a spaceship made from a hollowed-out asteroid, serving as a home for this generation with only one aim – to explore the Universe. The main protagonist – Zenon Belov – is the first child born on the Icarus, a true citizen of the asteroid.

A turning point in the novel is the trial of a scientist who created a cyborg child, programming it to play and learn, convinced that it is humans’ propensity for games that allows us to innovate and grow into individuals. But such experiments are forbidden, with robots permitted only as helpers to humans, not mimickers. Even worse, the little cyborg’s brainwave functions are identical to those of the scientist who created him – an attempt at cloning in its way. The child is killed, its creator frozen. A critical point is thus reached where Icarian society has to discuss whether it can allow changes to its stringent rules. The Icarus’s firstborn human, Zenon, sees it as a fool’s errand, a debate he is doomed to lose.

The book is a warning against a rule by experts, who might be great at keeping society running, but often don’t allow it to make the leaps forward it needs. While the Icarus flies, its people do not progress meaningfully until a few outliers – including someone who is born on the asteroid and thus cannot be satisfied by a novelty that for him is his whole life – shake things up.

Computers and robots held dangers, but also a promise, once humanity could see that it was a type of robot itself

Added to this, there is technological anxiety, too – what is it to be a man when there are so many machines? Thus, Dilov invents a Fourth Law of Robotics, to supplement Asimov’s famous three, which states that ‘the robot must, in all circumstances, legitimate itself as a robot’. This was a reaction by science to the roboticists’ wish to give their creations ever more human qualities and appearance, making them subordinate to their function – often copying animal or insect forms. Zenon muses on human interactions with robots that start from a young age, giving the child power over the machine from the outset. This undermines our trust in the very machines on which we depend. Humans need a distinction from the robots, they need to know that they are always in power and couldn’t be lied to. For Dilov, the anxiety was about the limits of humanity, at least in its current stage – fearful, humans could not yet treat anything else, including their machines, as equals.

Finally, it was Kesarovski’s time. He was a populariser of science, often writing computer guides for children, as well as essays that lauded information technology as a solution to future problems. This was reflected in his short stories, three of which were published in the collection The Fifth Law of Robotics (1983). In the first, he explored a vision of the human body as a cybernetic machine. A scientist looking for proof of alien consciousness finds it – in his own blood cells. Deciphering messages sent by an alien mind, trying to decode what their descriptions of society actually mean, he gradually comes to understand his own body as a sort of robot. Kesarovski’s vision of nesting cybernetic machines – turtles all the way down or up – indicates his own training as one of the regime’s specialists: he was a more optimistic writer than Dilov.

Yet, Kesarovski’s warning to humanity does come through in ‘The Fifth Law of Robotics’, his most famous story. It had already reached a wide audience, especially among young people, when it was serialised in the popular comic book Duga (‘rainbow’). In the killer-robot story that I opened with, the robot doesn’t know he is a robot, thus violating both Asimov’s First Law of Robotics (a robot must not injure a human) and Dilov’s Fourth Law. In Kesarovski’s telling, the Fifth Law states that ‘a robot must know it is a robot’. As the novella progresses, we face a cyborg that melds the best machine and human mind together, holding humanity hostage with its own weapons. While this Terminator-like story seems like a cliché now, it does end on a hopeful note, with a ‘robot psychologist’ recalling Christ’s words to Peter that he would betray him three times – and yet, on that stone he can build his church. For Kesarovski, computers and robots held dangers, but also a promise, if humanity could one day see that it was both a type of robot itself, and in a position only to gain from the machines’ powers, allowing it to attain the next step in its historical progress.

The propensity of Bulgarian authors to create laws of robotics became a subject of parody for another Bulgarian author – Lyubomir Nikolov. In his story ‘The Hundred and First Law of Robotics’ (1989), a writer is found dead while working on his eponymous story, which states that a robot should never fall from a roof. He himself is killed by a robot who just didn’t want to learn any more laws, resulting in the final one: ‘Anyone who tries to teach a simple-minded robot a new law, must immediately be punished by being beaten on the head with the complete works of Asimov (200 volumes)’.

Bulgarian robots were both to be feared and they were the future. Socialism promised to end meaningless labour but reproduced many of the anxieties that are still with us today in our ever-automating world. What can Man do that a machine cannot do is something we still haven’t solved. But, like Kesarovski, perhaps we need not fear this new world so much, nor give up our reservations for the promise of a better, easier world.