‘A banker and a theologian’ sounds like the start of a bad joke. But for David Miller it’s merely a job description. After working in finance and business for 16 years, Miller turned to theology, and received his PhD from Princeton Theological Seminary in 2003. Now he’s a professor of business ethics and the director of Princeton University’s Faith and Work Initiative, where his research focuses on Christianity, Judaism and Islam. ‘How to Succeed without Selling Your Soul’ is the students’ popular nickname for his signature course.

In 2014, Citigroup called. The bank had been battered by successive scandals and a wave of public mistrust after the financial crisis, so they wanted to hire Miller as an on-call ethicist. He agreed. Rather than admonish bankers to follow the law – an approach that Miller thinks is inadequate – he talks to them about philosophy. Surprisingly, he hasn’t found bankers and business leaders to be a tough crowd. Many confess a desire to do good. ‘Often I have lunch with an executive, and they say: “You do this God stuff?”’ Miller told me. ‘And then we spend next hour talking about ethics, purpose, meaning. So I know there’s interest.’ Miller wants people in finance to talk about ‘wisdom, whatever its source’. To ignore these traditions and thinkers, as the bulk of the industry tends to do, is equivalent to ‘putting on intellectual blinders’, he says.

Today, a banker listening to a theologian seems like a curiosity, a category error. But for most of history, this kind of dialogue was the norm. Hundreds of years ago, when modern finance arose in Europe, moneylenders moderated their behaviour in response to debates among the clergy about how to apply the Bible’s teachings to an increasingly complex economy. Lending money has long been regarded as a moral matter. So just when and how did most bankers stop seeing their work in moral terms?

In the early 1200s, the French cardinal Jacques de Vitry wrote a collection of exempla, morality tales that priests used in their sermons. In one story, a dying moneylender makes his wife and children swear to hang a third of their inheritance around his neck, and to bury him with it. His family does as instructed. However, later they decide to open the man’s grave to recover the money – only to flee ‘in terror at seeing demons filling the dead man’s mouth with red hot coins’, de Vitry wrote.

In de Vitry’s world, the moneylender deserved to be defiled by demons, because he’d committed the sin of usury – charging interest on a loan. De Vitry didn’t care whether the rate was high or low, because the Church’s position was that extracting a single cent of interest was evil. The roots of this revulsion run deep, and across cultures. Vedic law in Ancient India condemned usury, and rulers routinely capped interest rates from Ancient Mesopotamia to Ancient Greece. In Politics, Aristotle described usury as ‘the birth of money from money’, and claimed it was unnatural because money was sterile and should not ‘breed’.

Judeo-Christian religions cemented the usury taboo. The Old Testament reads: ‘Do not charge a fellow Israelite interest,’ and the Book of Luke advises: ‘[L]ove ye your enemies: do good, and lend, hoping for nothing thereby.’ In the 4th century CE, Christian councils denounced the practice, and by 800, the emperor Charlemagne made the prohibition into law. Accounts of merchants and bankers in the Middle Ages frequently include expressions of anguish over their profits. In his Divine Comedy of the 14th century, the Italian poet Dante Alighieri put the usurers in the seventh circle of Hell; in the case of Reginaldo Scrovegni, one Paduan banker singled out by Dante, his son ended up commissioning a chapel painted with frescoes by Giotto to expiate the family’s sin. Over the ensuing centuries, the philanthropy and patronage of other Italian Renaissance families such as the Medicis was partly inspired by guilt about how they’d profited from charging interest.

The stigma against moneylending continued well into the 1500s. To understand it, think about your reaction to the idea of a bank making a loan to a business at a 5 per cent interest rate. No problem, right? Now compare that to how you’d feel if your mother lent you money on the same terms. In Biblical times, the typical loan was more like the second case – it wasn’t an arms-length transaction, but a charitable loan from a wealthy man to a neighbour who’d experienced misfortune or had nowhere else to turn. Throughout early Medieval Europe, the local church or a wealthy family was often the only source of capital, especially outside the major commercial centres. Many peasants bought their land by getting mortgages from a monastery. In a world without credit markets and insurance, then, charging interest felt like extorting a friend or family member.

In Debt: The First 5,000 Years (2011), the anthropologist David Graeber argues that before the advent of money, economic life within a community was a web of mutual debts. People did not behave as self-interested individuals – at least not from the perspective of a single transaction; rather, they would share food, clothes and luxuries, and trust that their peers would repay the favour in return. When we consider these origins of debt and credit – as a system of mutual aid between people who trust each other – it’s no surprise that so many cultures viewed charging interest as morally wrong.

Moreover, as the economists José Scheinkman and Edward Glaeser have noted, usury laws also acted as a kind of social insurance that reduced inequality. Since charging interest (especially extortionate interest) was condemned, poor people could get emergency loans quite cheaply, and the rich couldn’t easily and passively turn their wealth into more wealth. At least that was the idea – in reality, people often turned to loan sharks, or to wealthy Jews who were quite literally demonised for moneylending.

Debt became essential to fighting wars, which both monarchs and the Pope needed to fund

Some historians and economists contend that the usury taboo was more about performance than reality. They argue that the moneyed class mostly ignored the prohibition – not least because it called for unrealistic levels of charity from the gentry. Merchants and bankers had all sorts of tactics for disguising the interest payments; one trick was for the parties to agree to use an overpriced exchange rate for the purchase of goods in the future. Or lenders made loans that didn’t pay interest, exactly, but instead promised a share of the profits from the borrower’s business. (This was a loophole, but it also ensured bankers got paid only if their loans benefitted the borrowers.)

Meanwhile, the Catholic Church played its own part in sowing the seeds of a change of attitude. In the 13th century, it developed the concept of Purgatory – a place that had little basis in scripture but did offer some reassurance to anyone committing the sin of usury each day. ‘Purgatory was just one of the complicitous winks that Christianity sent the usurer’s way,’ wrote the historian Jacques Le Goff in Your Money or Your Life: Economy and Religion in the Middle Ages (1990). ‘The hope of escaping Hell, thanks to Purgatory, permitted the usurer to propel the economy and society of the 13th century ahead towards capitalism.’

Even while clergy such as Cardinal de Vitry preached fire and brimstone against usury, the Church was increasingly willing to borrow money itself. Debt became essential to fighting wars, which both monarchs and the Pope needed to fund. Europe’s first real private bank had been founded in the 1100s by the Knights Templar, a Catholic military order that fought in the Crusades. The Knights protected pilgrims who travelled to the Holy Land, and this protection included safeguarding their funds by allowing pilgrims to deposit money in Europe and withdraw it in the Holy Land. Over time, the Templars offered a greater range of financial services; one of their loans relied on Crown Jewels as collateral. The Knights Templar disbanded in 1312, but other bankers extended the practice of lending until, by the 1500s, merchants were buying and selling business debts in fairs across Europe.

Eventually kings, politicians, and business people embraced usury wholesale, and the Church looked the other way. In 1462, Franciscan monks in Italy created the first non-profit pawnshops or monti di pietà (‘banks of piety’), which went on to spread across Europe. The idea was to be like a Grameen Bank in Renaissance Italy – a lender of last resort, displacing loan sharks who extorted desperate borrowers. The Pope went on to approve ever more kinds of financial instruments, until lending with interest was effectively allowed.

Despite the many loopholes and exceptions, usury laws still had teeth. ‘It would be a mistake to regard the Church’s sweeping prohibition as a sort of Volstead Act respected only by partisans, casually enforced, and lightly regarded,’ write the economic historians Sydney Homer and Richard Sylla in A History of Interest Rates (2005). So why did the prohibition on usury fade away?

One interpretation is that it was simply dogma – just like the belief that the Sun revolves around the Earth – that diminished in force as the Catholic Church splintered and lost political authority. Consider the Church like a business, whose core product was salvation, the economists Robert B Ekelund and Robert F Hébert have argued. When the Catholic Church held a monopoly in Europe, the clergy could ‘sell’ salvation at high prices – including strict prohibitions and purchased ‘indulgences’, which usurious sinners could buy in order to be absolved. But in the 1500s, during the Reformation, theologians such as Martin Luther denounced these practices. They advocated a more direct relationship with God that did not rely on priests as intermediaries, and founded new Christian movements such as Protestantism. The effect was that of a new company undercutting a monopoly. As Christian factions competed for believers, it led to a faith-based ‘race to the bottom’. And to increase their appeal, sects made fewer demands on believers – which meant weakening their stance on usury.

Here’s another view on why usury became less sinful: economic development eventually meant it wasn’t worth the trade-off. In 16th-century Europe, the economy was shifting from one defined by local agriculture to centres of commerce such as Florence. Global expansion made loans and investments more profitable, even as gold arriving from South America caused inflation. In these circumstances, the opportunity cost of not lending money grew higher and higher, as Scheinkman and Glaeser have argued.

In addition, the spread of banking ultimately transformed credit from a personal transaction between neighbours to a competitive, impersonal market. In The Idea of Usury (1949), the sociologist Benjamin Nelson argued that this institutional shift led Europeans to view moneylending more favourably during the Reformation. Luther interpreted Bible passages about usury, especially those that condemned charging interest on the poor, as calls to act generously. Usurers commit a sin, Luther wrote, only when their actions violate the do-unto-others principle – that is, only if ‘they do not want to be treated this way in return by others’. This reciprocity meant merchants and wealthy families were allowed to charge each other interest. Luther asked Christians to offer the needy charity rather than loans – but he still accepted interest rates under 5 per cent.

Surely we’re well rid of this moralising approach to finance? A world without interest payments would be one in which few people could access the funds they need to attend college, buy a house, or start a business. John Calvin, the French Reformation leader, thought it was immoral that his countrymen raised prices in order to take advantage of a flood of Protestant refugees who arrived in Geneva; but, just as surge pricing can recruit more Uber drivers on New Year’s Eve, we know that high prices also work to send a signal so that goods can flow to where they are needed.

But this isn’t the full story. The rise of debt wasn’t the Church simply bowing to the inevitable. Members of the clergy played an active role in creating the mindset that allowed usury to become respectable.

Scholastics understood the power of supply and demand, and argued that the just price was the market price

From the 1100s to the 1500s, clergymen known as the Scholastics debated whether lending was truly sinful. The Scholastics were the intellectuals of their day. They studied Roman law, Greek philosophy and Arab science at universities in Paris, Cologne, Vienna and others throughout Europe, and included luminaries such as Thomas Aquinas. They wrote and thought with the nit-picking particularity of lawyers. But despite the dry tone, the Scholastics could sound surprisingly like modern economists. Unlike previous generations of thinkers, who believed that prices should reflect the cost of production, many Scholastics understood the power of supply and demand, and argued that the just price was the market price. In one treatise, the prominent Italian Scholastic cardinal Thomas Cajetan analysed the ethics of how bankers hid interest payments in inflated exchange rates. It was equivalent to a cardinal in 2006 writing knowledgeably about credit-default swaps.

The Scholastics also recognised the value of taking business risks. Many of them sanctioned commercial loans to be repaid with a portion of profits. As long as the return was not guaranteed, because the venture could fail or collateral was unavailable, lenders deserved to keep the interest, they said. Some clergymen also realised that people who lent money were unable to use it on other profitable ventures. This is a very modern justification for permitting interest: opportunity cost. The price of borrowing money reflects the missed opportunity to invest it profitably elsewhere.

The Scholastics took finance seriously, but they always viewed it as connected to the domains of justice and natural law. Aquinas was not interested in narrow questions of maximising utility or channelling individual self-interest, as a modern economist might be; he and his peers wanted to know the just way to distribute wealth and how one could ensure economic exchanges were fair. In Summa Theologica (1265-74), for example, Aquinas argued that money’s ‘natural end’ or purpose was exchange. Using money to make money, rather than to facilitate the exchange of goods and services, therefore violated natural law. It was akin to selling wine or wheat separately from the right to consume these products – that is, like selling the same thing twice. ‘To take usury for the lending of money is in itself unjust, because it is a case of selling what is non-existent; and that is manifestly the setting up of an inequality contrary to justice,’ wrote Aquinas.

The thinking of the Scholastics and other religious leaders was not all admirable. Some clergy refused to budge from the literal words of the Bible, and others appealed to anti-Semitism to denounce usury. But their conversation represented an informed and influential debate – at the highest levels of academia and religion – about the entanglement of ethics, debt, inflation, high finance and monopolies. Where is that sort of thing today?

The Scholastics never resolved their disputes. Instead, they were replaced by new authorities on ethics and finance. It wasn’t until the rise of neoclassical economics in the 20th century that economics became the supposedly scientific study of self-interest and individual incentives – a domain in which economists do not pass judgment on actors in the market, any more than biologists would judge the ‘morality’ of bees, or engineers the ‘ethics’ of an aqueduct.

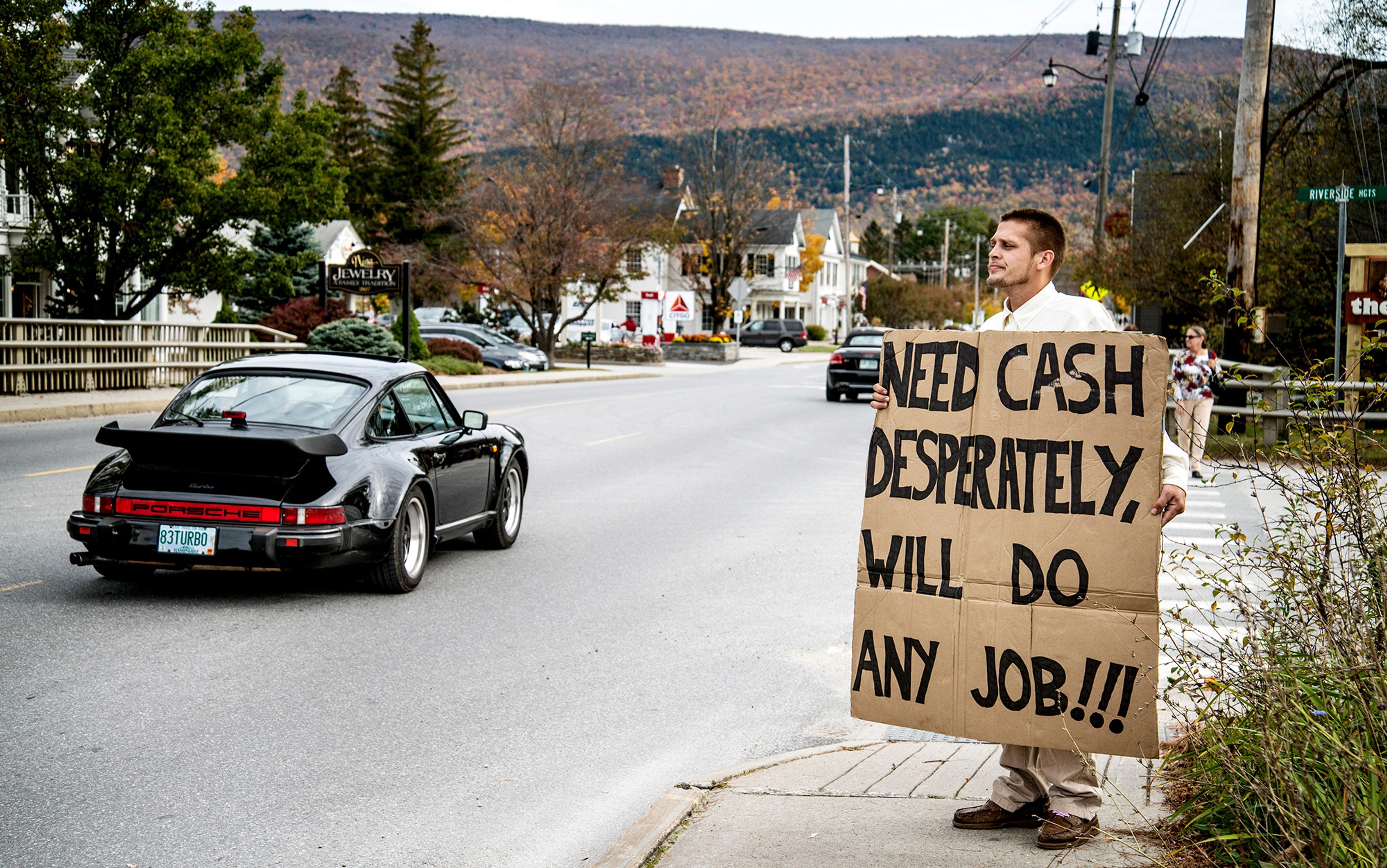

Of course, people today do discuss the ethics of finance. We debate whether bankers deserve lucrative bonuses; we worry about the moral hazard of bank bailouts; we condemn bankers who sell financial instruments that they know will fail. But since so much of the language of economics is amoral, and built on the assumption that everyone acts in their narrow self-interest, demanding just outcomes from finance feels like expecting fair results from war. We’ve lost the instinct that finance and debt are moral affairs all the way down, which is something that the Scholastics understood.

The public criticises bankers for their ethical failings, but the bankers too have been failed by our ethical authorities

So what would the Scholastics make of modern finance? Would they admire how efficiently a family’s savings can find productive uses? Or would they decry how developing countries pay more to borrow than rich ones? Would they marvel at our banks’ international reach? Or would they condemn how poor people pay for banking services such as checking accounts that rich people get for free?

It shouldn’t be so strange for a big bank to hire a theologian such as Miller; what should be strange is that we find it strange. It’s our modern talk of unfettered free markets and shareholder value that’s the anomaly. When Miller talks to bankers and executives, they often tell him that they feel as if what they learn in church or synagogue has no place at work. Even he was embarrassed about using the word ‘calling’ when he told his former co-workers that he was leaving for the seminary.

But neither secular nor religious authorities offer much guidance to bankers trying to link what they do to some kind of ethical tradition. In seminaries and divinity schools there’s a total lack of attention to the economy and the marketplace, Miller says. ‘Clergy may be quick to throw stones at the latest corporate excess on the front pages,’ he told me, ‘but there is not much constructive work.’ The public criticises bankers for their ethical failings, but the bankers themselves have also been failed by our ethical authorities.

Anyone interested in reclaiming ethics’ place in the world of finance, however, can build on a several-thousand-year-old foundation. ‘Aristotle, Kant, Bentham – are they dead people who have nothing of interest to offer?’ Miller muses. ‘Or were they on to something? Our economy would be unrecognisable to them. But the questions are still relevant.’