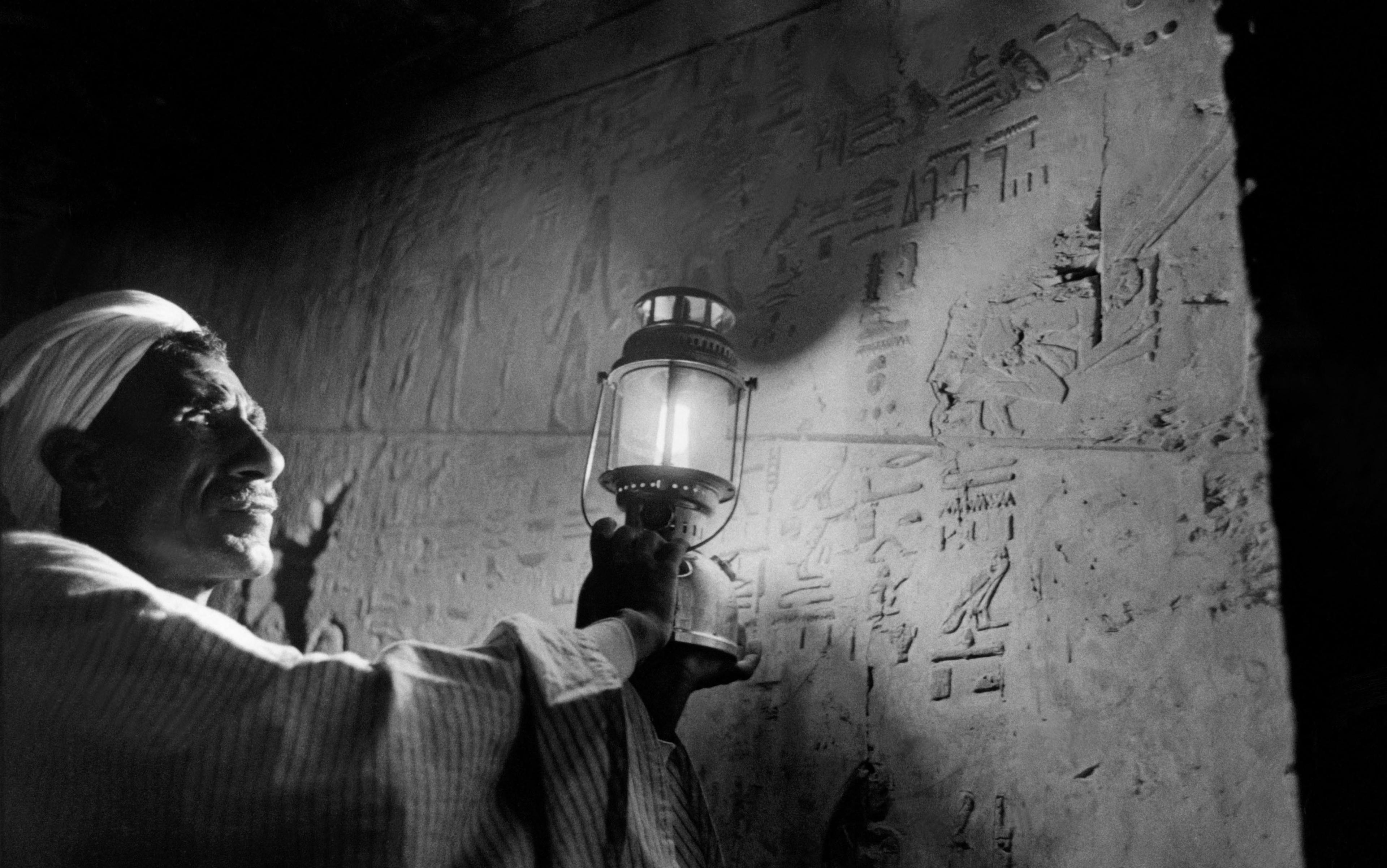

Consider the New Kingdom Egyptian. He can be forgiven for thinking his state sits at creation’s centre, a kernel of order anchoring the known world. If he lives during the reign of Ramses II, his Egypt has already governed Northeast Africa for the better part of 2,000 years. Trouncing Hittites at Kadesh, Ramses will confirm Egypt as the preeminent military power in the region and, for any Egyptian then living, the entire human fraction of the cosmos. That, at least, is what official accounts will show. Bombastic descriptions of the battle will decorate monuments across the empire.

A millennium and a bit later, not a living soul will be able to read them.

The scientific community has recently begun to think hard about natural and technological existential risks to human beings: a wandering asteroid, an unfortunately timed gamma-ray burst, a warming planet. But we should also begin to think about the possibility of cultural apocalypse. The Egyptian case is instructive: an epoch of stunning continuity, followed by abrupt extinction. This is a decline and fall worth keeping in mind. We should be prepared for the possibility that humankind will one day have no memory of Milton, or for that matter Motown. Futurism could do with a dose of Egyptology.

Western obsession with Ancient Egypt – Egyptomania – has always drawn on the split personality of its legacy: its suggestively modern face and its alien distance. Its zeitgeist is very nearly intelligible, but not quite. Here was a culture obsessed with writing. One Egyptian cosmogony gives credit to Ptah for creation through the Word, though other traditions put the cause down as Atum’s spit or semen.

Still, for all its carven glyphs, Egypt cannot claim to have passed down its dreams, memories and hopes for the future. Some of its civilisation has been recovered, but some was lost irretrievably. This is sobering enough on its own terms. When you examine our beloved present day from an Egyptological distance, you see that we are vulnerable to a similar fate.

The predicament is neatly captured in one of the best-known works of Egyptian literature, The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor. This Middle Kingdom story is exactly what it says on the tin, straightforward enough that its translation was assigned in my first year of Hieroglyphic Middle Egyptian at Yale University. The sailor of the title meets a ferocious storm, washes ashore on a phantom island, and enjoys several conversations with an impressively ornate serpent. The copyist scribbles: ‘His beard, it was more than two cubits long. His body was overlaid with gold. His eyebrows were lapis lazuli, truly.’ Enlightened, the sailor is duly rescued.

for the modern reader, the story’s ultimate meaning amounts to: huh?

Thanks to the survival of this particular papyrus, we have in hand the ancient bones of an adventure tale, one that’s washed ashore in virtually every cultural tradition (whether contrived independently or not). World literature is littered with shipwrecked sailors, cast overboard on this, that or the other mystical journey. Indeed, the story’s skeleton is recognisable enough that an illustrated children’s book edition is available.

And yet, the crucial ending of the story remains inaccessible. The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor is couched in a frame story; the account of wreck and recovery is meant to reassure a courtier, newly returned from a naval expedition to Nubia, as he readies to address the pharaoh. The tale’s sense – its moral – hinges on his response to this fantastic account.

That answer is a rhetorical question:

Who indeed? Well, scholars don’t exactly agree. Some see a glib dismissal of the sailor’s happy ending, others a reference to a very real ritual function. In any case, for the modern reader, the story’s ultimate meaning amounts to: huh?

What we have here is a failure to communicate. It’s as though an alien race has found Voyager’s Golden Record, the greatest hits of Earth-kind from Jimmy Carter to whale song. They manage to puzzle out its contents, and yet they find that it carries nothing but puns.

Without language, a people is left with very little. Think of Lee Harvey Oswald learning Russian in Don DeLillo’s novel Libra (1988): ‘Working with her, making the new sounds, watching her lips, repeating words and syllables, hearing his own flat voice take on texture and dimension, he could almost believe that he was being remade on the spot, given an opening to some larger and deeper version of himself.’ As Martin Heidegger put it in 1947: ‘Language is the house of Being. In its home man dwells.’

Imagine the pharaohs’ frustration at all the bits of language lost, the prayers and tributes especially. This was a civilisation that had its eyes fixed on eternity. Its civil calendar was apparently keyed to the heliacal rising of Sothis, whose astronomical cycle has a period of some 1,400 years. By dint of longevity, the first Egyptologists were Egyptian, and ditto the first tomb robbers. Is it a bridge too far to say the first futurists were Egyptian too?

And yet, its hieroglyphic script suffered through centuries of illegibility. The last hieroglyphic inscription – the last one with a convenient date attached – is at Philae, a small Nile island that hosted a temple to the goddess Isis (the island was recently submerged, and the temple complex relocated). That clutch of glyphs dates to 394 AD, but not until the 19th century would they be comprehensible again.

The trilingual stone saved what could be saved from an entire civilisation’s cultural memory

That the language was recovered at all is a minor miracle. In the years after its extinction, Egyptian refused to yield up its secrets to an onslaught of wrong-headed decipherments. Pseudo-scholars would read outlandish allegorical meanings into an ibis, the forelegs of a lion, a windpipe and heart. The language’s trick, of course, is that it isn’t fully phonographic or ideographic.

The Pharaohs and their scribes would be unheard until the French scholar Jean-François Champollion reached back through more than a millennium to rescue them. The tale of this miracle is shopworn. In 1798 Napoleon’s armies swept into Egypt with teams of scientists in tow, and stumbled onto the Rosetta Stone. They would later surrender the stone to the British, but casts of it circulated among European museums and scholars, including Champollion. The stone has become romantic shorthand for the cracking of a code, but it is, all things considered, an unexciting, bureaucratic text. And yet, it owes its air of romance to bureaucratic necessity, for the stone records the same message three times, in three scripts, one of which was well understood in Napoleon’s day. The trilingual stone saved what could be saved from an entire civilisation’s cultural memory. It was the time machine by which ancient Egypt travelled into the future.

Egypt’s story isn’t the only example of decline, fall and resurrection. The decipherment of hieroglyphs is a particular case of a more general problem: retrieving information across vast cultural divides and immense stretches of time is difficult. Cretan hieroglyphs remain impenetrable, Olmec – the language of the first major civilization in Mexico – is largely a mystery, and only within the past half-century or so has meaning been teased from the Mayan script. For every civilisation retrieved, another remains substantially beyond our comprehension. And for all the millennia it spent plotting immortality, Egypt’s resurrection was a happy accident.

But what if we could systematise that luck, to make sure that our own achievements never vanish? What if we could design a Rosetta Stone to be a Rosetta stone, on purpose – one that might someday rescue us from the dustbin of history?

When it comes to creating exceptionally durable records, the physical challenges aren’t half as intractable as they might seem. I put the issue to Anders Sandberg, a research fellow at the Future of Humanity Institute at the University of Oxford, who quickly listed a whole slew of plausible methods for very long-term information storage: write it into DNA, engrave it on glass or sapphire at the nano-scale, store it in a ‘million-year’ tungsten and silicon nitride hard-drive. The Moon, he volunteered, would be a better place to station an archive than Earth.

Of course, retrieving those records would be quite the feat. The institute’s director, Nick Bostrom, framed it to me this way: ‘It is one kind of challenge to preserve information that a technologically mature civilisation could eventually discover and retrieve, and another kind of challenge to preserve information in a form that would be helpful to a primitive civilisation that needs simple clues to help it back up to our current level.’ The first amounts to vanity publishing on an epochal scale, but the second just might keep the flame of our current civilisation alive.

‘We humans have figured out both honeybee dances and ant pheromone trails’

When constructing an archive for a stranger, it’s imperative to keep in mind the terms of discovery. How much information does the recipient need in hand to make sense of the archive, or to know that it is an archive in the first place? Bostrom told me it would be easy to communicate with a sufficiently developed species. ‘I think practically any record that we could create that we could also read,’ he said, ‘would be intelligible to an advanced future civilisation, provided only that we preserve a sufficient amount of text.’ Sandberg sounded a similar positive note: ‘We humans have figured out both honeybee dances and ant pheromone trails.’

If the arc of human history bends towards super-intelligence, our memories will be in good hands, but that doesn’t mean we’re in the clear. As Laura Welcher, a linguist with an interest in endangered languages, and the director of operations for the Long Now Foundation, put it: ‘In the very long term, I think we have to expect possible discontinuities.’ In that scenario, the challenge is trickier – how to create a library labelled, as simply as possible: ‘In case of apocalypse, read me.’

The Long Now Foundation in San Francisco has been puzzling over this problem. The foundation was set up 18 years ago to build a culture of extremely long-term thinking. Its house style is to write our current year as 02014 – to solve the Y10K problem, and to leave room for millennia 11 through 100. The Long Now is trying to do the opposite of archaeology. They are building ‘intentional artifacts’ in order to seed the world with secrets for the finding.

Last year, the foundation caught a flurry of attention for its 10,000-Year Clock: a timepiece sheltered in a Texas mountain, meant to run for millennia. The hook for most media outlets was the involvement of Amazon.com’s founder Jeff Bezos, whose maverick millions gave credibility to a project wrapped in fantastically romantic language. ‘[As] long as the Clock ticks,’ the foundation’s board member Kevin Kelly wrote for the project’s website, ‘it keeps asking us, in whispers of buried bells, “Are we being good ancestors?”’

Kelly always capitalises the Clock, and he likes to attach active verbs to it, as if the thing has a mind of its own. Steven Inskeep, the radio presenter of NPR’s Morning Edition, put the natural question to the Clock’s designer Danny Hillis: ‘Human nature being what it is, you still have to wonder if those future people discovering your clock might just go to wildly wrong conclusions – oh, this was their God that they worshipped in the mountain. Or who knows what else?’

That impression is, substantially, the point. The foundation wants its projects to have a ‘mythic’ feel, Welcher told me, the better to create a lasting community. The 10,000-Year Clock fits the bill, sitting right on the glinting knife’s edge between technology and magic. But this is just one way of being ‘good ancestors’. The Long Now has a smaller, and more plainly useful project that draws on the decipherment of Egyptian. An archive of human language, it could fairly be described as a whole world in your hand. The Foundation calls it the Rosetta Disk.

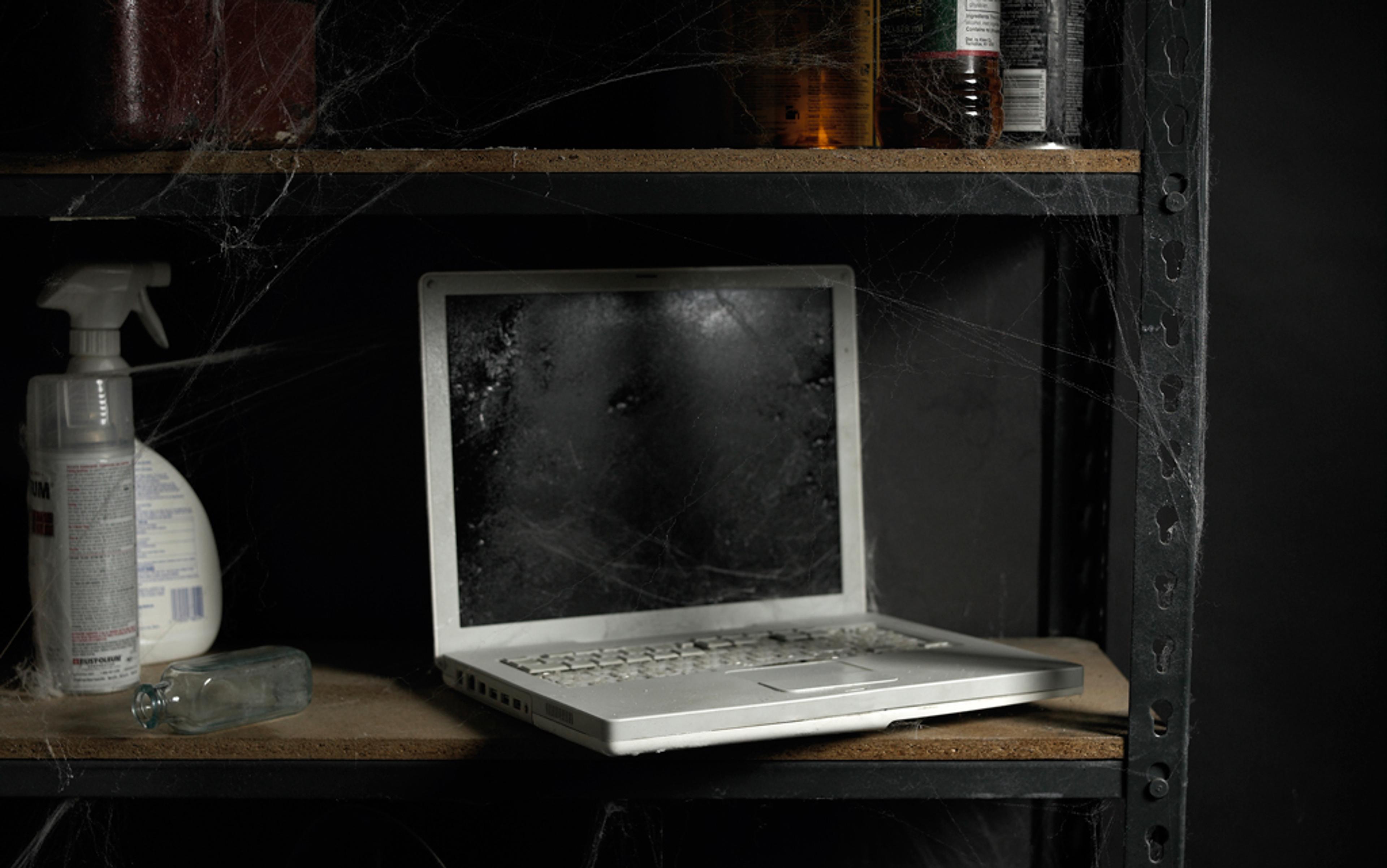

Digital formats decay at extraordinary speed. Egyptian papyri have endured. On millennial scales, go analogue

The Rosetta Disk takes the principle of the Rosetta Stone to its practical extreme: massive parallelism for maximum intelligibility. A nickel puck just 2.8in across, the Disk is etched all over, microscopically, with more than 13,000 pages in more than 1,500 languages. Champollion, eat your heart out. A glass globe shelters the Disk against wear, tear and elemental abuse. This isn’t the library itself, emphasises Welcher, who heads the Rosetta Project. Instead, she calls the Disk a ‘decoder ring’ or a ‘card catalogue’. It’s the map, not the territory – a means of (re)discovery, in case all else is lost.

In designing a ‘library of civilisation’, the Long Now didn’t look to Voyager-style probes or cutting-edge hard drives. Instead, Welcher says, the challenge was: ‘Can we do better than paper?’ Digital formats decay at extraordinary speed – blink and you miss them. Indeed, some NASA data was temporarily lost due to software and hardware change. Egyptian papyri have endured. On millennial scales, Welcher advises, go analogue.

The other design challenge was to signal the Disk’s content. Reading it requires an optical microscope, which means that a reader must have reason to think that the Disk should be examined under a microscope.

This design problem becomes tricky over very large timescales, especially if the archivist assumes nothing of her audience’s language skills and technical development. It’s a question that comes up when nuclear waste sites are discussed: how do you communicate ‘do not dig here’ across time, to people for whom most of your signposts are unintelligible? Some have suggested that grotesque sculptures could do the trick, but those sculptures could be interpreted as hiding treasure. In 1984, a pair of linguists proposed creating ‘ray cats’ that would glow in response to radiation. They would then compose a folklore of songs and tales that would preserve the notion that glowing cats signal danger. Carl Sagan, clearly phoning it in, recommended a skull and crossbones.

The foundation’s solution to this problem is elegant, a shrinking, in-spiraling inscription that reads ‘Languages of the World’ in English, Spanish, Russian, Swahili, Arabic, Hindi, Mandarin and Indonesian. So long as one of those languages lives, the Disk’s pitch – ‘Read me!’ – is legible. But where to put it? If mass distribution can’t be managed (the Disks are fairly expensive), the setting ought to communicate the artifact’s importance. Take the Phaistos Disk, a resolutely mysterious object recovered from beneath a Minoan palace on the Greek island of Crete. Its glyphs remain un-deciphered, but its preciousness is announced loud and clear by its burial underneath a palace. So long as we treat our intentional artifacts with a certain degree of reverence, future re-discoverers will plausibly do the same.

The Long Now Foundation has found at least one symbolically resonant home for its Disk. A copy is ensconced on Rosetta, the European Space Agency’s comet probe, whose plucky lander was named for Philae. As long as the Rosetta Orbiter circles the Sun, it guards the memories of the whole human race.

The canonical allusion for ephemerality is Percy Bysshe Shelley’s sonnet ‘Ozymandias’ (1818), Ozymandias being another name for Egypt’s Ramses II. As the line goes: ‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings/Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’ ‘Nothing besides remains,’ writes Shelley. ‘Round the decay/of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare,/the lone and level sands stretch far away.’

Shelley’s poem is the best known, but Horace Smith’s on the same subject, which was published a month after his friend Shelley’s, better suits the futurist lens. Smith wrote:

We wonder, – and some Hunter may express

Wonder like ours, when thro’ the wilderness

Where London stood, holding the Wolf in chace,

He meets some fragment huge, and stops to guess

What powerful but unrecorded race

Once dwelt in that annihilated place.

Consider Smith the father of Egyptological futurism. But whatever precautions we take against cultural annihilation, one intractable problem remains. There is a gorgeously convoluted name for those words that, in a given corpus, appear only once: hapax legomena. Any beginning student of hieroglyphs is bound to come across these in Raymond O Faulkner’s Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian, and they tend to spark equal parts despair and delight. Delight because you can be sure you’ve gotten the transliteration right, and your work is done. Despair because, if thin context clues don’t suffice, there is no puzzling out what it means. The word is quite simply dead.

When a word goes, a bit of the culture goes with it. The losses snowball, referents fade, and allusions die with them. ‘Who,’ after all, ‘gives water to a goose as the land brightens for the morning of its slaughter?’ Bostrom’s caveat strikes back. Everything is recoverable, ‘provided only that we preserve a sufficient amount of text.’

The solution is only partly technical. Even paper is technology enough for the next few millennia. The challenge is to maximise the surviving corpus. Egypt’s literate classes fell foul of that calculus, guarding jealously the hieroglyphic script. The first commandment of Egyptological futurism, then, would be to ward off at all costs the dead words, those blasted hapax legomena. In other words, for humanity’s sake – write.