In the Gardens of Babur in the Afghan city of Kabul stands a tree. It is now a bullet-riddled trunk in a garden originally built by the founder of the Mughal Empire. When the Taliban ruled Kabul, municipal services faltered, and the cold winters forced neighbours to cut down many of the garden’s trees for fuel. Today, it is restored with new flowers and trees; a haven from the overcrowded city, a balm from the many years of violence. Except for this one trunk. In a city that doesn’t need any more reminders of what it has endured, this tree trunk was like salt on a wound.

I have spent many years working with Afghans, first with refugees in Canada and Pakistan, and more recently in Afghanistan itself. Until 2015, when the Syrian civil war overtook it in the rankings, Afghanistan produced more refugees than any other country in the world – for 32 years in a row. In 2000 in Pakistan, I stood in a refugee camp for Afghans and heard laughter. Resilience, I thought: extraordinary resilience from intense experiences of trauma and loss.

Resilience is attracting more and more attention from scholars of psychology. This is largely as a result of increased understanding and awareness of human suffering following traumatic events, including the experience of becoming a refugee after a war. The term ‘resilience’ has its root in resilientia, which means ‘to avoid or recoil’. It connotes elasticity of ‘resuming an original shape or position after compression’. You bend or you break, as they say. The interest in resilience comes from wanting to help people to bend, rather than to break, and learning from those who seem to have not broken.

Resilience, as an idea, carries an association with strength of will. To be able to resume an original shape in the aftermath of trauma is often considered laudable, and those who are able to ‘bounce back’ and recoil in the face of adversity should be admired. Though recoil appears in the context of resilience, as a term it often surfaces in discussions around firing a gun. Each bullet that escapes a gun requires a certain force of momentum. Recoil equals this force of momentum pushing back against the gun and the person holding it. In this equation, there is some sense of balance: momentum forward equals the momentum backwards – forgetting, of course, the broader story that should be told each time a bullet leaves a gun.

This broader story is underserved in the resilience literature today.

Hannah Arendt wrote in Crises of the Republic: On Violence (1972) that ‘events, by definition, are occurrences that interrupt routine processes and routine procedures’. There are some events that happen in life that cause people to cross a threshold that forever changes them, whether they seek out their transformation or not. Life is ever unfolding, and people are ever in a process of becoming. Resilience holds the etymological implications of resistance to crossing thresholds, and instead adapting an old self to new circumstances without offering space or time to be completely changed by new realities.

The desire to witness resilience in another is, perhaps, fuelled by a scarcity approach to time. In the westernmost part of Canada sits the archipelago of Haida Gwaii where the indigenous community of the Haida people live. I was struck by the wisdom of their leadership, which, I was told, does not think in terms of election cycles, decades or even centuries. Instead, they think in terms of 10,000 years. In this way, time transforms from a scarcity into something else entirely: it stretches and develops depth. This abundance is reflected in many of the world’s life philosophies. These traditions are deeply entrenched in the rhythms of the Earth, and draw out wisdom that can be found in the nature of seasons, the cycles of day and night, even in the trees. In this extended form of time, resilience becomes transfigured from the urgency associated with a need for recoil into something that takes its time, and resembles patience.

Patience, in its original meaning, was a virtue that enabled a person to overcome his suffering and, in some sense, enact understanding in the face of the faults and limitations of others. Patience today might conjure a sense of inactivity, a feeling that it’s about more or less waiting for things to pass. Consider, instead, the term patient. As an adjective, it is the quality of a person who is able to overcome and demonstrate understanding towards others. As a noun, it is a person who is in need of understanding and, specifically, medical care.

Patience recognises suffering in the difficulties of one’s life and that of another. Nowadays, it might conjure up ideas of complacence but, with a long view of time – in which time is understood as abundant – patience becomes a way of bearing sorrows. Unlike resilience, which implies returning to an original shape, patience suggests change and allows the possibility of transformation as a means of overcoming difficulties. It is a simultaneous act of defiance and tenderness, a complex existence that gently breaks barriers. In patience, a person exists at the edge of becoming. With an abundance of time, people are allowed space to be undefined, neither bending nor broken, but instead, transfigured.

And it is an act of courage, because only the unknown lies on the other side of the threshold of events we seek to overcome.

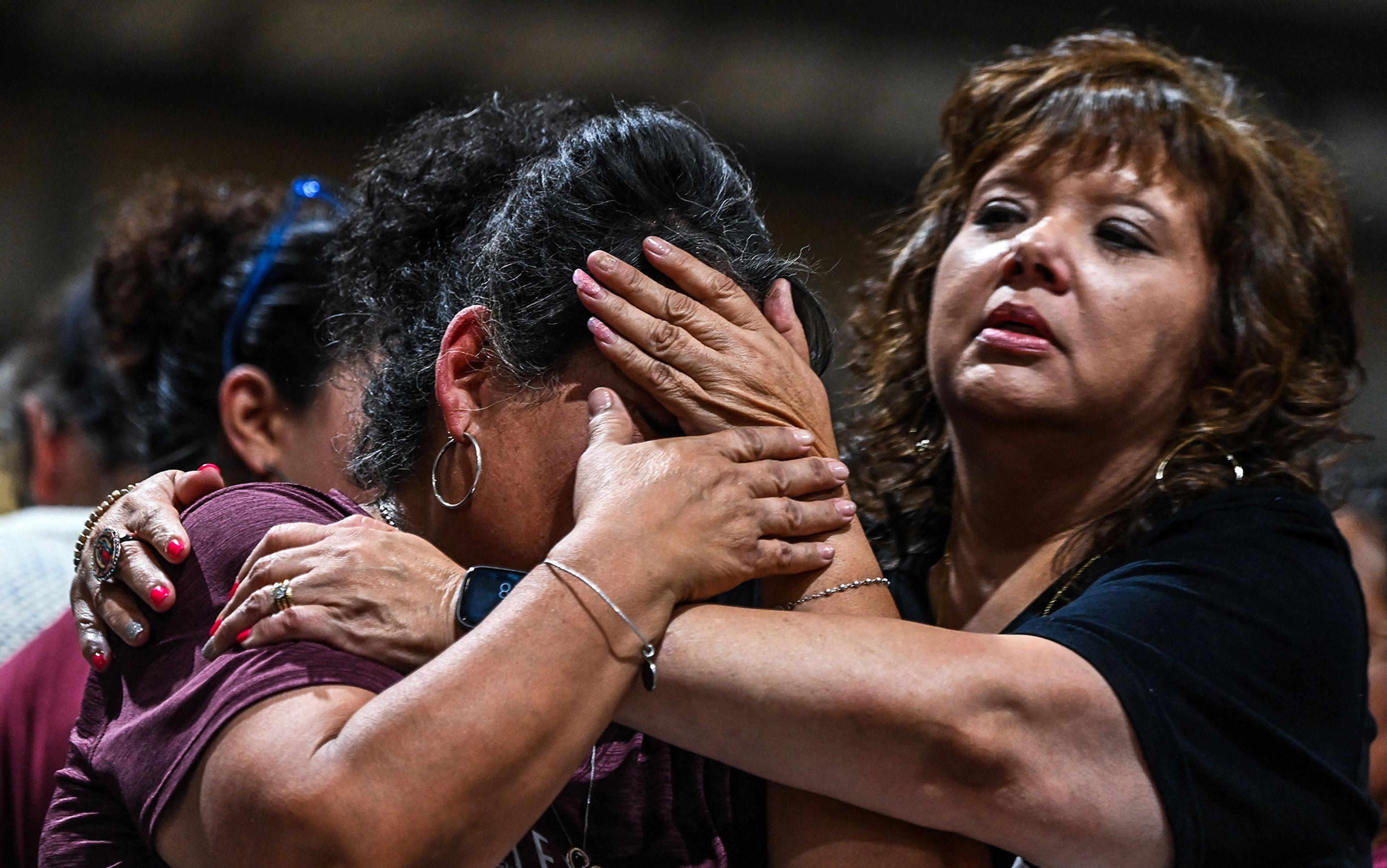

Almost every Afghan has lost a loved one to violence. After 11 years of working in Kabul, my family still had not. It seemed we had slipped quietly past the gods of war. Then, on 20 March 2014, four Taliban entered the hotel in Kabul where my mother was staying and pulled out small guns hidden in their shoes. The attackers, whose fake IDs suggested they were in their early 20s, looked as though they were still teenagers. They were just boys. My mother was at the hotel restaurant, meeting with a friend to discuss the ways in which they could support the education of young, hopeful Afghan students. They killed her and her friend.

In the shadow of the violence that stole my mother, I felt a sense of urgency. I wanted to demonstrate resilience. If my will was strong enough, I felt, I could use it as a kind of hammer to beat my life back into proper shape. All I wanted was to return to my original self; I wanted to recoil.

It was impossible. My approach to grief became externalist; though I had become, in a non-medical sense, a patient, I was also acting as my own doctor. I had never grieved before, never witnessed grief so closely. In that time, it looked a lot like a disease to me, one that I had to cure quickly. I have since come to realise that haste to recoil, to return to original form after trauma, constitutes another form of violence. I found no peace in the rush. My sense of urgency was physically manifest in my sudden need to run. For hours each day I would run, pushing myself to every physical and emotional limit imaginable.

In the days following my mother’s murder, the word martyr came up several times. It is a label that carries baggage, both as a term of praise and as a concept associated most often with violent death. In the Islamic context, it is also a word that is tied to the concept of jihad, a controversial term that implies both warfare and internal struggle within oneself to become free of one’s inner demons. Unlike its current connotations of dying for a religion, martyrdom once meant, in both the Christian and the Islamic traditions, to live by the tenets of a faith, to live as testimony to a religion. It was only in the context of religious persecution and violence that martyrdom took on the meaning of one who dies for her faith. Originally, martyrdom was to bear witness by actions throughout life.

My mother’s martyrdom was then not her death, but her life. To see her death as an act of martyrdom is, in some way, to tolerate this violent act. Her death was senseless and achieved nothing but hurt for the family that loved her. But, each day of her life was a struggle to share what she saw as her greatest privileges: her time and her knowledge. These she gave freely to the Afghan children who still refer to her as ‘Mum’. As a witness to her daily efforts, I watched my mother endeavour to enact patience. She spent her first year in Afghanistan learning. Though she could have lived a more comfortable life, she was sure that she could help only if she understood what it meant to be cold in the winter without firewood, or left without electricity or running water for weeks at a time. It was a year that changed her and, though it was arduous, she endured it with patience that found understanding on the other side.

My mother was killed on the eve of the Persian New Year – Navroz – a celebration of the Spring Equinox. I was in Vancouver, where around this time the cherry blossoms begin to bloom. Navroz is an agrarian celebration, calling attention to the earth and human dependence on the harvest. In many agrarian societies, time is understood as a circle in which the seasons turn back on to one another. This can be likened to the circular motion of our breath with every inhale and exhale of air a person makes. In this way, time can be reconceived as something more than a resource. Instead, it becomes a friend, mirroring the most innate act: breathing. In breath lies the root of the spirit, for the word spirit is derived from the French esprit, or breathing. For me, there was comfort in the spiritual world of Sufism.

It poignantly captures the deep loss and longing for loved ones, and finds comfort in the process of becoming offered by grief

In the days and weeks following my mother’s death, I turned to a book of poetry written by the Sufi mystic Hafiz. My family had given it to me for my 16th birthday, in Kabul. This poetry spoke to me in ways that the poetry of Rumi or others could not. After learning more about Hafiz’s life, I began to understand why his work was so powerful.

Hafiz was born in 1320 in Shiraz, a Persian city with resplendent gardens. After losing his father at a young age, Hafiz worked hard to attain an education, studying the great Persian poets of his age, including Saadi and Rumi. He fell in love, and had at least one child. As a poet who was dependent on the patronage of the elite, he spent a large part of his life in poverty. The irreverent quality of his work, which often suggested he and God were lovers and drunks, earned him exile from Shiraz for several years. His wife and then his son died. His work poignantly captures the deep loss and longing for loved ones, while also finding comfort in the process of becoming, which grief offers. In his poem ‘Tell Me of Another World’, Hafiz writes:

‘Tell me of another world,’ the broken heart

says, ‘one where love is never sad it loved,

and the word sorry never comes to mind.’‘Show me dear God, that anything I have ever

wept for will return, will reside, in my arms.’

Throughout his life, Hafiz sought the advice of another Sufi poet from Shiraz, Attar, who became his spiritual guide. Their relationship evolved over daily conversations, meals and walks in the gardens of Shiraz. Hafiz was desperate for enlightenment, to which Attar counselled patience. For 40 years, Hafiz struggled with his longing for answers to life’s great questions. Over the course of those years, his poetry beautifully reflected this struggle: a lifetime of patience. In ‘Heaven Is Jealous’, Hafiz writes:

And there are gods who would trade their lives

To have a heart that can know human pain,

Because our sufferings will allow us to become

Greater than any world or deity.

In my grief and struggle for patience, I found myself witnessing the journey of Hafiz. In his words, I felt understood. Separated by time, geography, language and culture, Hafiz and I were in communication, walking our own journey through the field of the unknown.

Several months after my mother was killed, I was helping to relocate a pear tree from a learning garden in Vancouver. I spent hours digging around its roots so as to give it the best chance of life in its new home, another garden not far away. As I dug, I recalled the tree in Kabul. The bullet-riddled trunk was more than a reminder of environmental loss. That tree in the historic garden demonstrated something I came to understand in the months following my mother’s death: the resilience of resuming our shape before trauma strikes is an impossible request of our souls and our spirits.

In whatever we do, we do not forget the pain of the past, but rather hold it and the joy of the present, simultaneously. This trunk of a tree, riddled with bullet holes, stood as proof of the shallowness of resilience. To remove it and create a space that had erased the trauma of the garden’s past is akin to asking someone to return to the person they were before a life-changing event. As it stands in the garden, that tree trunk now is a quiet champion of patience, a movement to endure. And it bears witness to all those who have crossed its path.

I think of the tree trunk in Kabul often. The city’s landscape will forever hold the scars of what happened to its people. The holes left behind by bullets stand as witness to the lives lost and the millions of refugees who are no longer home. From this landscape, I take the lesson that I need not be who I once was, that I may hold my scars and my joy simultaneously. I need not choose between bending or breaking but that, through patience, I may be transfigured.