Long before current fears about incivility in public life – before anxieties about Twitter-shaming and cable-news name-calling – politeness was very much on the minds of United States leaders. In 1808, the US president Thomas Jefferson ranked the ‘qualities of mind’ he valued. Not surprisingly, he included ‘integrity’, ‘industry’, and ‘science’. These traits were particularly important to American revolutionaries seeking a society based on independent citizens, rather than harsh rulers and inherited privilege. But at the top of his list, Jefferson chose not these familiar Enlightenment values but ‘good humour’ – or what contemporaries usually called ‘politeness’.

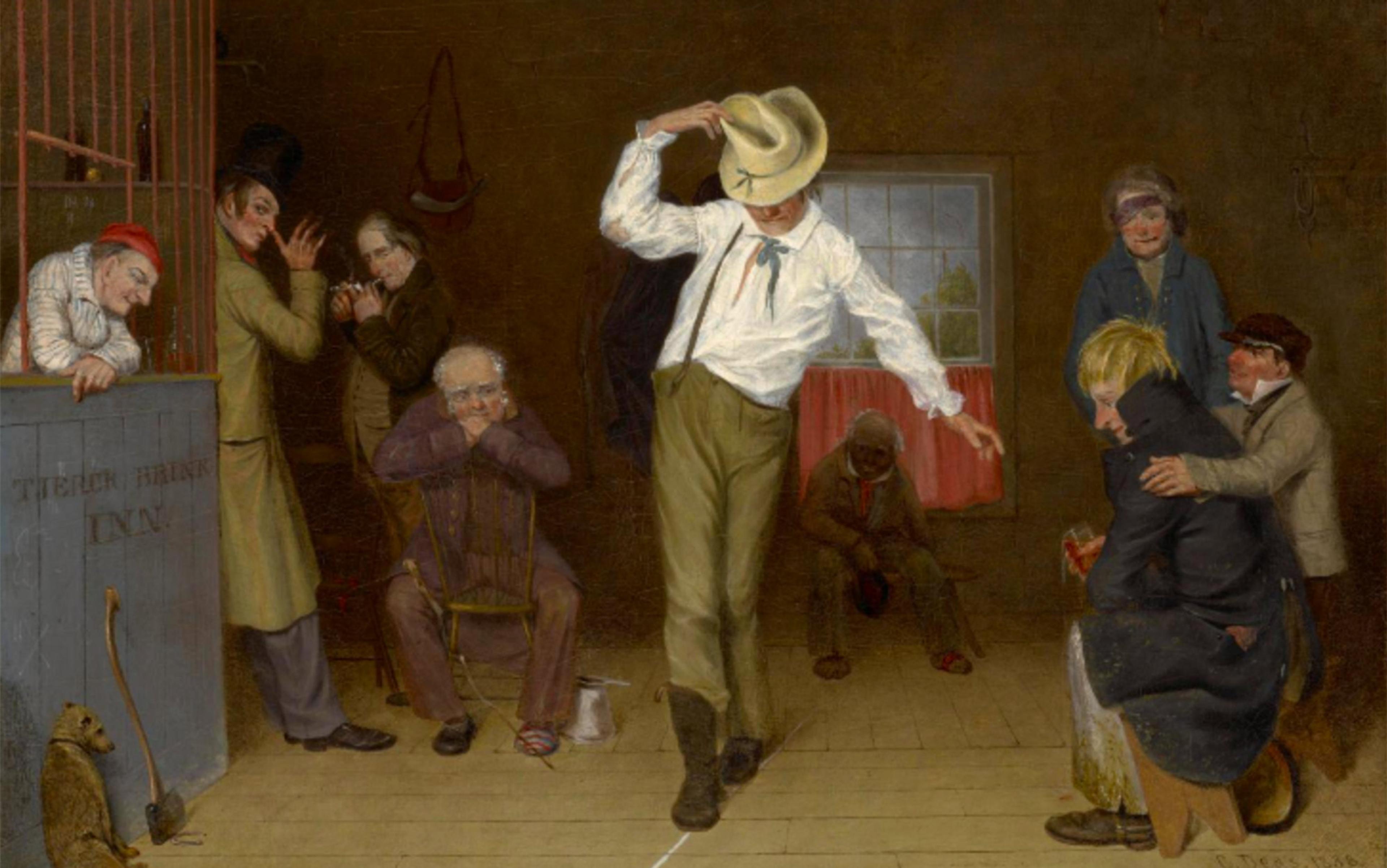

Placing politeness first seems surprising. Today, the term often connotes a lesser, private virtue, reminiscent of antiquated childhood rules and required thank-you notes. At worst, politeness keeps people from revealing themselves or speaking out against injustice. One of the longest-running US reality TV shows, The Real World (1992-), suggests in its introduction that the truth about who people are comes out only when they ‘stop being polite – and start getting real’.

However, 18th-century Britons and Americans believed that politeness was essential for a free society. Autocrats shouted, cursed and berated. But they sought only obedience. Leading a more open society required respect for other people, sensitivity to their expectations and concerns. By the time of Jefferson’s ranking, politeness had been part of the project of challenging authoritarian rule for more than a century.

Later in 1808, Jefferson explained the importance of politeness more fully. The president’s 16-year-old grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, had recently left home for further education in Philadelphia. ‘Safety’ in this situation, Jefferson suggested, required three qualities: moral virtue, ‘prudence’, and ‘good humour’ supported by ‘politeness’. He explained further that politeness was ‘artificial good humour’, the habits and discipline that filled in when good humour flagged. It was, therefore, ‘an acquisition of first-rate value’. Consideration for other people, refraining from disputes in company, and sacrificing one’s own ‘conveniences and preferences’ to please others could ‘win’ their ‘good will’.

Jefferson was not saying anything new. His grandson could already have studied The Polite Student (1748) and The Polite Philosopher (1736) – or works offering the ‘Complete art of polite correspondence’, ‘the principles of politeness’, or ‘the character of a polite young gentleman’. Randolph’s mother might have read The Polite Lady (1760).

But Jefferson also knew that politeness was complicated. The term originally meant polished or smooth. As ‘polite’ came to be applied to humans as well as things towards the end of the 17th century, it became linked to the emerging ideal of refinement. Contemporaries celebrated (or moralised about) ‘polite society’ and the ‘polite world’, sometimes in ‘polite literature’.

‘Politeness’ differed from related terms such as ‘gentility’ and ‘civility’ because it focused on human interactions. Jefferson’s call to ‘conciliate’ other people highlighted this distinction. In 1702, the prolific writer Abel Boyer suggested that ‘politeness’ meant ‘a dextrous management of our Words and Actions, whereby we make other People have better Opinion of us and themselves’. Or, as Benjamin Franklin put it simply in 1750: ‘The polite Man aims at pleasing others.’

Britons and Americans of the 18th century applied these ideals of sympathy and respect to public as well as personal relationships. Seeking restrained and responsive leadership, the 18th-century ‘politics of politeness’ offered a powerful challenge to angry and overbearing authoritarian rule. For many contemporaries, this critique often seemed broader and more compelling than the discussions of legal and constitutional issues that are better known today.

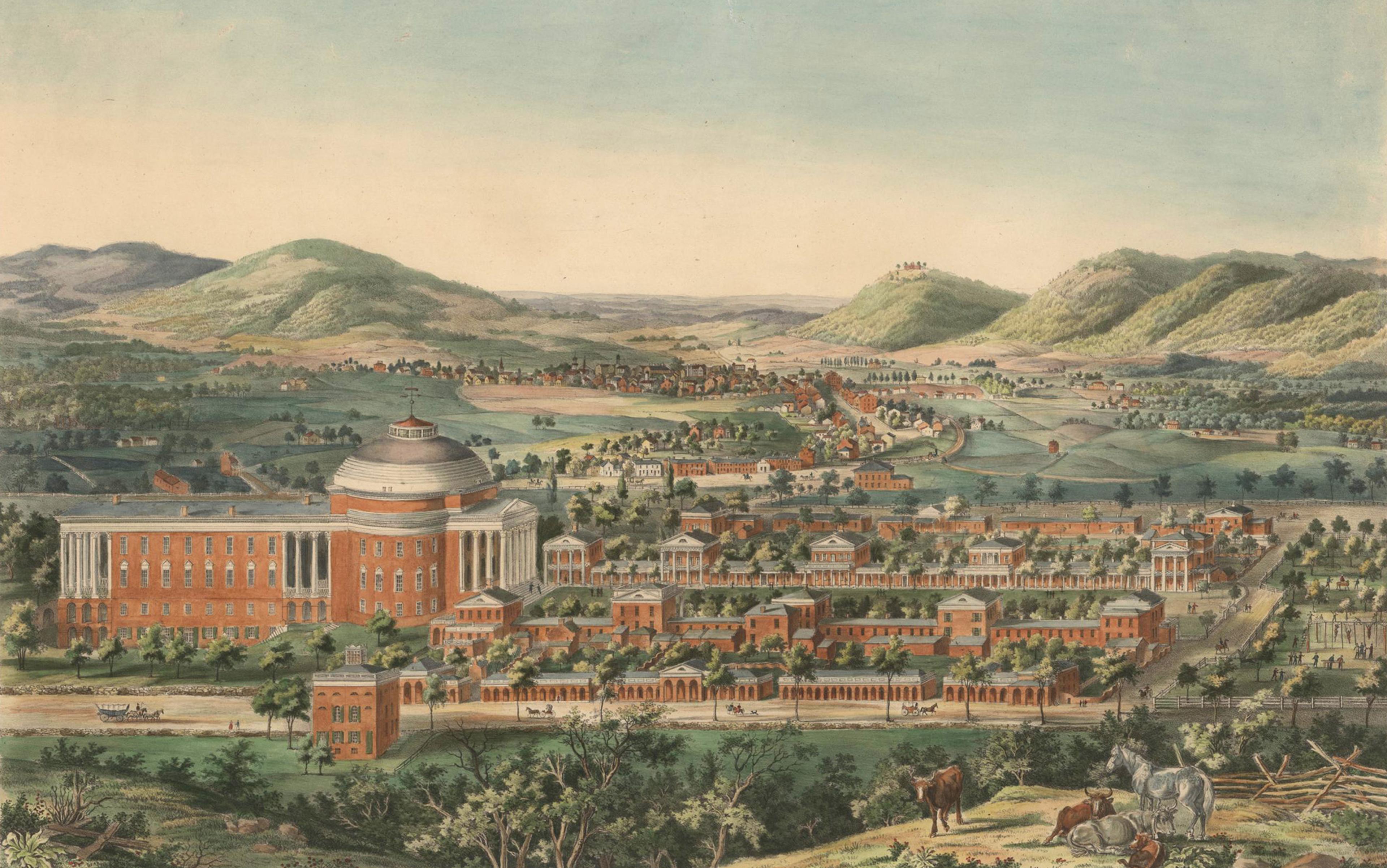

Politeness developed in Britain, and Europe as a whole, but its political applications became especially important in 18th-century British America. The culture of restrained power helped to shape and sustain the more stable native-born elites that also emerged there around the turn of the 18th century. In turn, politeness played a powerful role in the American Revolution. By the time that Jefferson wrote to his grandson, however, the bonds that held these values together were beginning to break apart. These developments – what might be called the secret history of politeness – appear clearly in the experiences of two Virginia governors, not only the polished Jefferson himself but also a decidedly impolite predecessor, Francis Nicholson, the half-mad martinet who served at the start of the 18th century.

Nicholson even frightened some of Virginia’s greatest leaders. ‘Nobody went near him but in dread & terour,’ noted James Blair, president of the college in the colony’s capital, and a former supporter of the man who served as its governor between 1698 and 1705. Nicholson ‘governs us,’ Blair complained, ‘as if we were a company of Galley slaves.’ Nicholson called the colony’s leaders ‘dogs, rogues, villains, dastards, cheats, and cowards’; its women ‘whores, bitches, [and] jades’. When a young woman spurned Nicholson’s romantic advances, he told another minister (in a six-hour tirade) the affair ‘must end in blood’.

Nicholson’s rages expressed his political as well as personal concerns. An English-born military officer who had previously served in a garrison in northern Africa, Nicholson formed part of the advanced guard of British royal government in North America. His American career began in the mid-1680s as captain of a company of troops serving the Dominion of New England, a newly formed province placing England’s northern colonies under a single royal governor without a countervailing legislature. Nicholson’s final posting, as the first royal governor of South Carolina, ended 40 years later, in 1725.

For the better part of a century, Britain had paid relatively little attention to its emerging North America colonies. Near the end of the 1600s, however, that began to change. Colonists bridled at this new imperial discipline. In 1689, Massachusetts leaders imprisoned the royal governor, the hated Edmund Andros. Nicholson, fearing the same fate, fled New York after another uprising erupted there. Rebellions against local and imperial authorities spread throughout the colonies during the 1670s and 1680s. In 1676, Virginia insurgents burned its capital.

Whigs emphasised the obligations of rulers alongside the duties of the ruled

England itself had been similarly volatile. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 marked the second time that the country had dethroned a monarch in a generation. The English Civil War of the 1640s had been even more tumultuous. For more than a decade, rebels removed the monarchy and church from their place at the head of English society. The king was even tried, and condemned, for high treason.

Nicholson was horrified by these outrages upon what he called the ‘most sacred’ monarchy. He set out to reinforce royal authority at every turn. In Maryland, where he served before becoming Virginia’s governor, Nicholson designed Annapolis with the centres of authority, the capitol and the church, on its two highest hills. In Virginia, he issued even the smallest spoken orders ‘in the queen’s name’. When the colony’s attorney general questioned him, Nicholson grabbed him by the collar, insisting he should be ‘obeyed without hesitation or reserve’. Frustrated by members of the college’s board, he threatened to ‘beat [them] into better manners’.

Nicholson’s six-hour tirades and quick resort to threats might have been unusual, but his authoritarian stress on obedience was not. Many Britons shared Nicholson’s views of monarchy and social hierarchy. In the wake of the Civil War, politicians and church leaders ceaselessly preached the obligations of nonresistance and unlimited submission. Indeed, after 1680, such ideas became the ideological foundation of the new and powerful Tory party.

Not all Britons agreed, however. The Whig party rejected the Tory Party’s strenuous support for hierarchy and obedience. ‘Arbitrary’ government, authority unrestrained by legality, custom or public feelings, was dangerous. Whigs similarly rejected harsh measures and demands for complete conformity, supporting what they called ‘moderation’. Whigs did not recommend disobedience. But they emphasised the obligations of rulers alongside the duties of the ruled.

The deep divisions of Nicholson’s world fuelled more than political turmoil. The emerging ideals of politeness supported peaceful interactions within a divided social and political landscape. But politeness was not politically neutral. Its call for sympathetic concern for people’s sensitivities challenged authoritarian ideas, a lesson not lost on the Virginia leaders who finally dislodged Nicholson from the governorship in 1705.

Although Edward Nott, the more genial army officer who replaced Nicholson, served for only a year and left no lasting accomplishments, the colony loved him. Blair praised Nott’s ‘very calm healing Temper’, and his ‘moderate temper’. The legislature erected a memorial to him a dozen years later that praised the ‘mildness’ of his administration. The original draft of the inscription detailed the political implications of praising Nott’s moderate temper. It celebrated Nott for being unwilling ‘to make his Power absolute, and his Government arbitrary’.

The Virginia leaders who resisted Nicholson formed part of a series of increasingly stable and self-confident American-born elites developing up and down the seaboard. These new groups found the politics of politeness particularly appealing. Its ideals and practices helped colonial leaders create a working relationship with the newly intrusive imperial government. Politeness also helped them win over local communities similarly skeptical of the demands of new colonial elites. By the time colonial elites helped lead their colonies into a revolution, the politics of politeness formed an essential part of their lingua franca.

Even captive enemies, Thomas Jefferson had argued, should be treated ‘with politeness’

In 1781, Virginia faced a British invasion. The would-be independent state was ill-prepared and ill-defended. Yet Jefferson, its governor, remained philosophical about his lack of power. When the Marquis de Lafayette arrived with patriot troops, Jefferson warned that Virginians, blessed with ‘Mild Laws’, were not used to ‘prompt obedience’. As a result, government orders were ‘often ineffectual’. Lafayette in return promised to adapt to the ‘temper of the people’.

Jefferson and Lafayette’s extraordinary acceptance of limits on their power (so unlike the impatient Nicholson) points to the formative influence of the politics of politeness. If Revolutionary leaders were not all as cautious about demanding obedience, they still brought with them almost a century of thinking about the need to ground power in restraint and responsiveness. Tellingly calling themselves ‘Whigs’ (and their opponents ‘Tories’), patriots celebrated their military leader, the Virginian George Washington, as a powerful exemplar of these values. Jefferson reported to the general in 1784 that many Americans believed his ‘moderation and virtue’ had kept the Revolution from ending like ‘most others’ – by destroying the ‘liberty it was intended to establish’.

The politics of politeness also helped revolutionaries reconsider social relationships. Resisting attempts to punish loyalists after the war, Alexander Hamilton declared the spirit of the Revolution ‘generous’ and ‘humane’ – and therefore in the best tradition of ‘moderation’. Even captive enemies, Jefferson had similarly argued earlier, should be treated ‘with politeness’. Abigail Adams counselled legal changes in her call to ‘Remember the Ladies’ in 1776, but conceded that new laws were needed primarily for the ‘vicious and Lawless’. More enlightened men, Adams noted, had already willingly ‘give[n] up the harsh title of Master for the more tender and endearing one of Friend’.

The contrast between master and friend, harsh and tender, also shaped Jefferson’s most compelling critique of slavery. The most intractable of American problems, human bondage, had become the central labour system of the American South during the disordered years of the late 17th century. Writing a century later in the 1780s, Jefferson argued that the search for complete control over slaves undermined the foundations of the republic. Slaveholders engaged in the ‘most unremitting despotism’. People in bondage felt no loyalty to master or nation. The evil effects of the institution even corrupted the children of slaveholders. Observing (and then imitating) their parents’ fury, they were ‘nursed, educated and daily exercised in tyranny’.

In early 1809, soon after advising his grandson about joining the ‘wide world’, Jefferson declared his desire to return home and become ‘the hermit of Monticello’. Jefferson had been forced upon the ‘boisterous ocean of political passion’, he wrote to a friend, but his imminent retirement from the presidency would allow him to enter the ‘harbour’ of ‘my family, my books, & farms’.

Sympathy and self-control remained important cultural touchstones but, increasingly, in a separate category

Jefferson’s distinction between the troubling political world and the soothing home became a 19th-century commonplace, familiar even today. But its very success has obscured the earlier politics of politeness with its stress on the continuity between public and private life. Jefferson had previously portrayed the southern home as a training ground for tyranny – arguing that, to use a later phrase: ‘The personal is political.’ His talk of returning to his ‘fireside’ involved a rhetorical retreat as well, abandoning his condemnation of the slave system that sustained his domestic comforts.

The 19th-century turn from the politics of politeness, however, did not repudiate its values. Jefferson continued to be convinced that political life required a constant battle against forces that rejected faith in the people. And the US political culture he helped to shape was often obsessed by the dangers of arbitrary power and unresponsive leadership. Sympathy and self-control remained similarly important cultural touchstones. But, increasingly, they seemed to belong to a separate category.

The persistence of these divisions testifies to their power. But, in contentious times when the public world once again seems angry, harsh and even dysfunctional, it might be helpful to reconsider the narrower views of politeness that have prevailed for so long.