To an unusual degree among the great philosophers, G W F Hegel’s influence has waxed and waned. At his death in 1831, he was the reigning voice in German philosophy. His followers, however, soon split into opposed camps: the Right Hegelians, a conservative and religious group, and the Left Hegelians, a socially radical group including Karl Marx. Amid their squabbles, Hegel’s star began to fade in Germany. But in the late 19th century, it once again rose to prominence in the rest of Europe and in the United States. Certain strains of 20th-century Continental philosophy were deeply marked by his influence, such as French existentialism and the Frankfurt school of critical theory. But 20th-century Anglophone philosophy reacted strongly against the neo-Hegelian thought that dominated the universities at the end of the 19th century. In English-speaking lands (including the US), Hegel has lived under a cloud for the past century: his writing too dense, his ideas too abstract, his politics as well as his theology too suspect. His works have been treated with derision in mainstream Anglophone philosophy, and excluded from the canon that trained philosophers need to master.

The logjam that blocked English-language Hegel studies, however, is finally crumbling, and a number of Americans are leading the way. Again, Hegel’s star rises. It isn’t outlandish to suggest that the new openness to Hegel marks an important inflection point in US philosophy.

Hegel’s reception in the US has long been complicated. In the mid-to-late 19th century, he was widely read and respected. There were several well-established groups, often heavy with German immigrants, dedicated to Hegel study, such as the Ohio and the St Louis Hegelians. There were prominent Hegelian Idealists in the universities, notably Josiah Royce at Harvard and G Watts Cunningham at Cornell. And, perhaps most important, several Pragmatists, especially Charles S Peirce and John Dewey, were influenced by Hegel. (William James was not a Hegel fan.) Then the reaction set in. It started in England, with Bertrand Russell and G E Moore’s revolt against the British Idealists, but the Americans picked up the banner and then doubled down on the rejection of Hegel with the infusion of logical positivists escaping Nazi Germany in the 1930s.

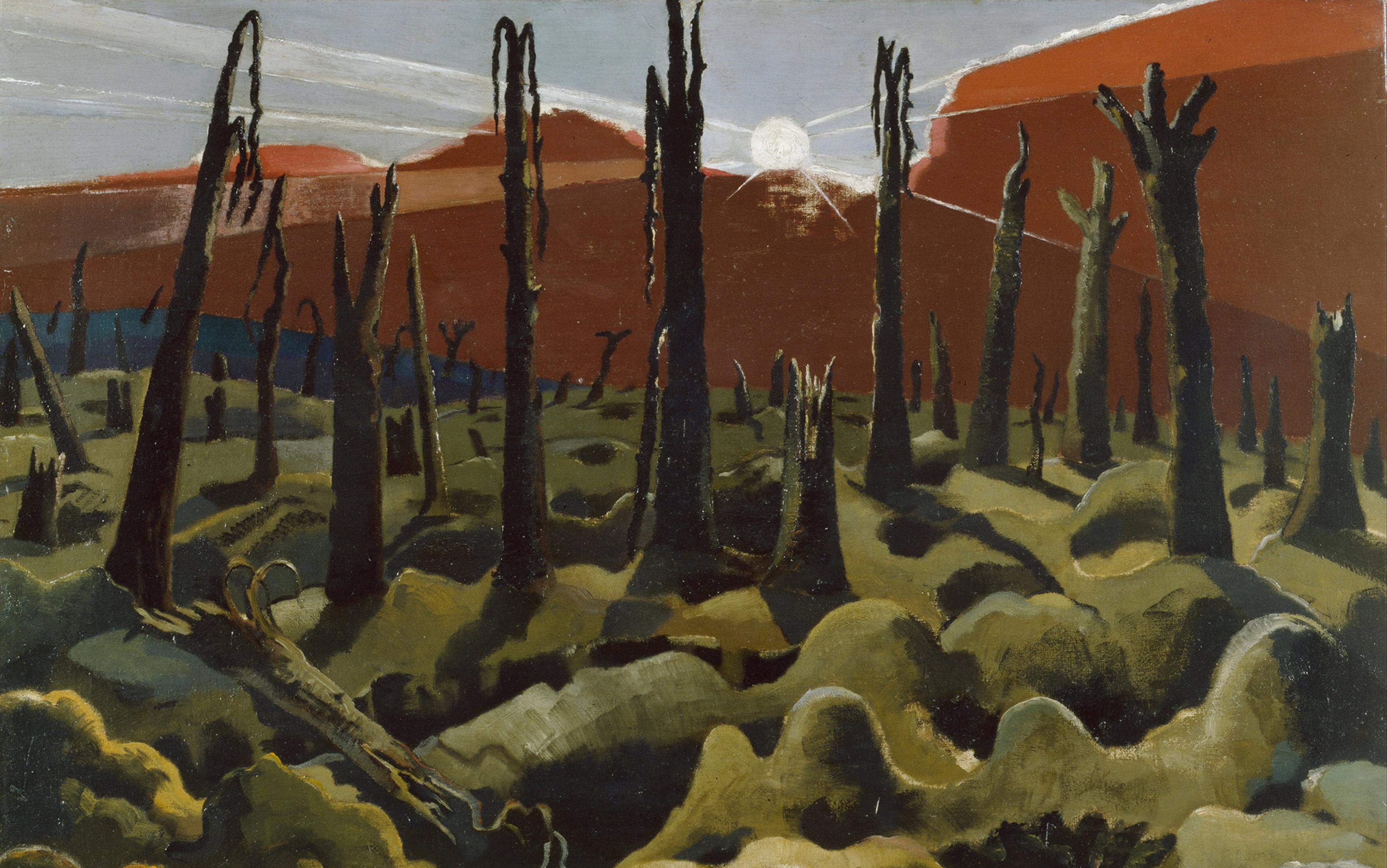

Portrait of G W F Hegel (1831) by Jakob Schlesinger at the Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin. Photo courtesy Marcel Molina Jr/Flickr

Anglophone philosophy turned against Hegel for several reasons. His philosophy was seen as the epitome of a grand metaphysical system purporting to lay out a priori the fundamental structure of reality, which turned out to be mental, or in Hegel’s vocabulary, spiritual – something like a world soul, or (even worse), a Spinozistic, pantheistic God. Thus, not only was Hegel’s system grandiose metaphysics, it was grandiose theology as well. Hegel also defended a holism that conflicted with the atomism (and the foundationalistic theory of knowledge) that comes naturally with empiricism and which seemed to be a lesson taught by modern science. Hegel’s philosophy opposed the antimetaphysical, atomistic, foundationalist and empiricist bent of Anglophone philosophy, which was also increasingly secular in orientation.

At a slightly less abstract level, Anglophone philosophy had become enamoured of the developments in logic initiated by George Boole, Gottlob Frege, and Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead. Investigations into logic, generalised into the philosophy of language, became first philosophy in Anglophone lands. From this perspective, Hegel’s logic (arguably the heart of his philosophy) was either terribly retrograde or, in all its talk about dialectic, hardly intelligible. And last, the obscurity of Hegel’s writing made rejecting Hegelian philosophy all the easier. After all, who could tell what he was actually saying?

The renaissance in Hegel appreciation that has bloomed in the past few decades in the US responds to most of these complaints. It has been led by Robert Pippin, Terry Pinkard, and Ken Westphal. Most recently, Robert B Brandom’s massive volume on Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit (1807), called A Spirit of Trust (2019), has gone beyond Hegel interpretation to elaborate a philosophy that, while still rooted in the philosophy of language, also reclaims Hegel as a (maybe even the) seminal forebear.

The initial move by Pippin and Pinkard, writing in the late 1980s and early ’90s, was to argue for a ‘non-metaphysical’ reading of Hegel. Such a reading sees Hegel’s philosophy as an extension and radicalisation of Immanuel Kant’s; it emphasises the respects in which Hegel, like Kant, is critical of the rationalistic metaphysics that believes the fundamental truths governing the world can be known a priori through reason alone. Hegel, they say, is not investigating some supersensible reality. He is instead investigating the categories we use to think about and act within the world.

Spirit is not some transcendent entity above and beyond the world. Neither is it simply identical to the material world. Rather, Spirit is identified with the social world and, especially, the normative structures that constitute human social interactions and, especially, human rationality. Such normative structures are necessarily embodied in material conditions and activities, but they cannot simply be identified with naturalistically (ie, non-normatively) described activities of material bodies. Take chess as an example of a normative structure. An action such as making a chess move cannot simply be identified with a particular motion in space, because chess moves first need not require any particular motion, since one can play chess not only with different kinds of chess pieces, but without any pieces at all, and, second, it must be performed by agents following widely recognised and historically developed rules. Hegel’s story about the development of Spirit is a story about the evolution of the normative structures both realised in and governing human social structures and interactions – structures that make rational thought possible.

Semantic theory is key to the revival of Hegelian thought

This view of Hegel’s project addresses the supposed metaphysical grandiosity of the Hegelian system: it is not a knowledge of some otherworldly entity or realm, but an attempt to organise the knowledge (both theoretical and practical) accrued over history concerning the sensible and social world in which we live. Nor is the Hegelian system aprioristic: Hegel explicitly allows for the ongoing historical development of the categorial scheme in terms of which the world is to be articulated. That is, while Kant thought that the categorial scheme that structures thought is fixed and immutable – simply given to us – Hegel recognised that human thought has been developing and refining itself over time, not just by the accrual of new particular facts, but also by reorganising them in new ways and developing new methods for revealing, even creating, new kinds of facts. There is room in the dialectical development of our categories to accommodate empirical discoveries that lead to new ways of thinking, such as the development of Newtonian mechanics. The historical consciousness in Hegel’s philosophy is an attractive point for many who find the ahistorical approach of mainstream Anglophone philosophy blindered.

Any real revival of Hegelian thought among Anglophone analysts, however, would need to overcome the atomistic foundationalism that originally inspired analysis. That is where Wilfrid Sellars, who did not identify as at all Hegelian, enters the tale. Sellars is an interesting figure. He thought of himself as an analytic philosopher: together with Herbert Feigl, originally a member of the Vienna Circle, he compiled the first canonical textbook of analytic philosophy and in 1950 founded Philosophical Studies, the first English-language journal explicitly devoted to analytic philosophy. But Sellars was widely read in both historical and contemporary philosophy, in Continental as well as in Anglophone philosophy. He simply did not draw the boundaries that many ‘analytic’ philosophers drew.

Prior to Sellars, ‘analytic’ philosophers took the idea of ‘analysis’ dead seriously: they sought to isolate the fundamental ‘atoms’ of which our knowledge and experience – indeed, the world itself – were composed, and then to show how the structures of knowledge, experience and the world resulted from construction in accordance with the rules of modern logic. They sought to update a basically empiricist philosophy that derives ultimately from the work of David Hume and John Stuart Mill. Recognising this empiricist bent of Anglophone philosophy, Sellars sought to move it to a more sophisticated Kantian stage that does justice to the fact that the representationality (or intentionality) that underlies all knowledge and experience is never atomistic, but always systematic, and always subject to norms, to standards of correctness.

Sellars attacked atomism and foundationalism in his essay ‘Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind’ (1956). Despite its length, this turns out to be just the outline of a rich, complex revision of mainstream epistemology and philosophy of mind in mid-20th-century Anglophone philosophy. It presciently foreshadowed many of the developments in the late 20th century. One important dimension of Sellars’s view was a semantic theory that differed just enough from the then-dominant theories to enable Sellars’s followers to begin to make sense of Hegel’s logic, a major step towards resuscitating Hegelian philosophy. Brandom’s contribution to the recent ‘non-metaphysical’ interpretation of Hegel is that semantic theory is key to the revival of Hegelian thought, so let’s examine it closely.

The analytic tradition relied on what seemed to be a straightforward conception of semantics. Whereas syntax concerns intralinguistic relations (wellformedness, rules for composition of legal strings of the language), semantics – the discipline concerned with specifying the content of linguistic expressions – concerns the relation between language and the world. But Sellars denies that semantics requires a basic word-world relation at all. Rather, the content of a linguistic expression – and also the content of a concept or a thought – is a matter of the proper inferential relations it bears to other expressions or thoughts. So semantics is primarily a matter of word-word relations, instead of word-world.

In explicating this ‘inferentialist’ theory of meaning, Sellars extends the notion of inference to cover not just the formally valid inferences explored in formal logic – inferences that depend only on the syntactic structure of the sentences involved, and, thus, inferences in which the non-logical words are irrelevant to the validity of the inference – but also material inferences. Material inferences are inferences whose validity is not guaranteed by the syntax of the sentences alone. For example, the inference from ‘The ball is red’ to ‘The ball is coloured’ is not formally valid, but it is a perfectly good inference.

In Sellars’s view, semantics is not all about intralinguistic connections, for our responses to the world around us, called language-entry transitions (or observation reports), and the way we act on our stated intentions and desires, called language-exit transitions, are also important elements in the constitution of meaning. How one interacts with the world (and with other people) is important for interpreting one’s beliefs and desires. The result is that the content of a word or sentence, and equally the content of a concept or thought, is determined by its position within a complex linguistic economy that includes observation reports, inferences, various speech acts, etc, all responsive to norms of proper usage.

This is a holistic and non-foundationalistic semantics, for there are no expressions whose content is determined independently of other expressions in the system. Sellars’s younger colleague Brandom picked up this thread of Sellars’s thought and brought to the fore the fact that our concepts have histories, stories about how they came to have the connections that make them the concepts they are. Brandom then used this view of semantics to interpret Hegel’s conception of dialectic. Brandom includes not only material connections between concepts, but also material exclusions: what a concept excludes or is materially incompatible with is no less significant for its content than what it entails or is entailed by. Colours cannot have mass, for instance; a fish cannot be warm-blooded. Such incompatibilities help interpret the notion of determinate negation that Hegel makes much of. According to Brandom, writing in A Spirit of Trust:

As a matter of deep pragmatist semantic principle, the only way to understand the content of a determinate concept, [Hegel] thinks, is by rationally reconstructing an expressively progressive history of the process of determining it.

This is as true for our categorial concepts – the concepts by which we organise our arsenal of first-order concepts – as it is of those first-order concepts, which apply directly to objects, events, etc. For instance, in ‘The tennis ball is yellow’, ‘tennis’, ‘ball’ and ‘yellow’ are all first-order concepts applied to a particular object. Categorial concepts classify other concepts into conceptual kinds, as in ‘Yellow is a visual quality; ball is a geometric shape.’ There are various kinds of qualities – visual, tactile, etc – and various kinds of shape properties – sphere, cube, torus. Brandom thus fleshes out Sellars’s original semantic vision in ways that connect directly to Hegel’s thought. Let’s now unpack what Brandom means by ‘rationally reconstructing an expressively progressive history’ of the determination of a concept.

Understanding a determinate concept requires a ‘rational reconstruction’ of its history

The content of a concept is determined by its position in the network of inferential relations and real-world applications in which it plays a role. It is not the job of philosophers to determine the contents of most first-order, empirical concepts, such as ‘magenta’ or ‘elephant’. The philosopher’s job does concern determining the contents of categorial concepts, those high-level ideas that organise the bevy of lower-order, empirical concepts: what makes something a cause or a substance.

The contents of the subjective concepts we employ in coping with the world around us are not fixed and immutable. There are several sources of change in such concepts. Experience is one important source: the European concept of swans changed when black swans were discovered in Australia. Empirical science can amplify such changes: we now possess a far more refined concept of, say, water or matter than our predecessors hundreds of years ago. Normally, experience induces change in our first-order empirical concepts, but categorial conceptions can also be influenced.

The history of enquiry is thus a story in which our conceptions of causation and material objecthood have also changed. For that matter, empirical investigations are not the only sources of conceptual change, for developments in religion and the arts, in politics and philosophical reflection also influence the changing profiles of our concepts. Equality of the sexes is now regularly acknowledged in the West, though not as regularly practised – a significant change from earlier eras. One problem, however, is that not all conceptual change is for the good. For instance, there are now compelling arguments that the concept of race is a relatively late addition to the conceptual arsenal of Western culture and by no means a salutary one. It enabled arbitrary and invidious distinctions among people, and supported the unjust oppression of a large number of humans. Yet it is also an important concept in understanding current social structures and practices; we cannot simply cease to use it anymore.

This is why Brandom (speaking for Hegel) thinks that understanding a determinate concept requires a ‘rational reconstruction’ of its history. Such a rational reconstruction is a reasoned and evidence-based story about how and why the concept came to have the role, the inferential connections, that it does. In many cases, that story will provide a justification for the continued use and development of a concept. In some cases, it might limit the realm of application or even undermine our entitlement to continue using a concept, pushing its development in a very different direction. Sometimes it will justify abandoning the concept altogether and assigning it a purely historical role, as happened with phlogiston.

Concepts to be retained and developed will have an ‘expressively progressive history’. Those we (ought to) abandon or limit, such as phlogiston or race, will not. An expressively progressive history will be one that exhibits the use of the concept, over the course of its history, to be ever better, to be a steadily improving (though perhaps not without occasional setbacks) expression of the concept as it is in reality. Dictionary definitions are, therefore, terrible ways to determine the content of a concept; at best they are a mere snapshot of the current state of things. A true determination of a concept’s content would be an historical account exhibiting how the concept came to have its current role in our behavioural economy. The same applies to explicating the content of a principle. Of course, not every concept or principle ends up revealing aspects of the truth, and thus not every explication of them will end up vindicating the concept or principle. At any point in history, some concepts will be in jeopardy, not clearly supported by an expressively progressive history. Items like the concept of phlogiston or the principle of white supremacy will be so explicated that their lack of vindication is exhibited.

In explaining his vision of how concepts unfold dialectically, Brandom exploits an analogy to judicial reasoning in common law. The concepts and principles of common law have never been explicitly and precisely formulated. In fact, they could not be finally, once and for all, settled, for they could not be specified in sufficient detail to apply without further judgment given the details of the cases. That is, they are necessarily subject to adaptation and refinement in response to new or changing conditions. Each judge renders an opinion on a particular case in the light of the recorded facts of the case and the established precedents. The kicker is that a judge can decide that some previous cases were wrongly decided, that some precedents are more probative than others. That judgment, in turn, might be overturned. There is no limit or end point where everything is finally settled, no ultimate judge.

Humanity’s attempts to discover the truth and do what’s right are to be seen as engaged in a similar, ongoing back-and-forth among the players. The procedures of common law move towards justice insofar as the judges are sincerely dedicated to ‘getting it right’, uncorrupted by personal, political or religious considerations, even as we recognise that there are no ideally objective judges. The societal process that Brandom models on common law can hope to move further and further towards the truth only to the extent that the contributors are sincerely (and rationally) striving in good faith to achieve truth and foster human flourishing. Society can achieve its ideal state only if a compassionate, forgiving spirit of trust pervades and prevails among its agents. Hegel’s dialectic is not so much an abstruse philosophical methodology as it is an idealisation of the process by which imperfectly rational, finite thinkers reach for stable, enduring truths. In A Spirit of Trust, Brandom tells us that Hegel’s philosophy includes

a semantics that is morally edifying. For properly understanding the conditions of having determinate thoughts and intentions, of binding ourselves by determinately contentful conceptual norms in judgment and action, turns out to commit us to adopting to one another practical recognitive attitudes of a particular kind: forgiveness, confession, and trust … A proper understanding of ourselves as discursive creatures obliges us to institute a community in which reciprocal recognition takes the form of forgiving recollection: a community bound by and built on trust.

Brandom’s approach shares much with that of the ‘non-metaphysical’ Hegelians, but there are some significant metaphysical commitments hidden within it. Notice that, for Brandom, ‘concept’ and ‘principle’ are ambiguous: there is (a series of) human or subjective concepts-of-x, mental representations specifiable to particular times, places and cultural communities, and then there is the concept, the objective concept-of-x, the full truth, the ideal towards which the series of particular human concepts aims. Brandom is committed to the (subjective) reality of the particular, embodied, localised concepts-and-principles operating in people’s minds and to the (objective) reality of concepts-and-principles that are, in some perfectly good sense, ‘out there’ in the world, independent of any thinkers. Brandom takes concepts and principles to have both a subjective and an objective reality – in that regard, like Plato. However, the objective reality of concepts and principles, according to Brandom, is not to be found in some supersensible reality known only by pure, intuitive reason – in that regard, like Aristotle. Brandom takes it that concepts are embedded in the forms of things themselves. He thinks that the objective, sensible world is ‘always already in a conceptual (and so, ultimately, thinkable, intelligible) shape that it does not owe to any activity by the thinking subjects to whom it is in principle intelligible’.

If it is raining, we ought to think things outside will be wet. If it is raining, then, necessarily, things outside will be wet

Thinking through these claims takes us a bit deeper into Brandom’s theory. The inferential connections that are constitutive of the content of a concept are modal connections, what is necessarily connected to a concept and what is merely possibly connected to it. Perhaps there are other modalities as well, such as what is probably or typically connected, what ought to be connected and what ought not to be connected. Traditionally, empiricists, following Hume’s example, tend to be very sceptical about the objective existence of such modal connections, since they are not available directly from sensible experience. Brandom’s rationalism sees no reason to doubt the objective reality of modal properties and relations ‘out there’ in the world.

Indeed, Brandom goes further than endorsing a straightforward modal realism. While objective concepts are embodied in and determined by the alethic modal properties and relations among the objects of the world (what is necessarily or possibly connected to what), he also believes that our subjective concepts are embodied in and determined by the deontic modal properties and relations among our concepts of the objects of the world (what one ought to think, or is permitted to think, given what else one thinks). Our epistemic goal is to bring into correspondence the deontic properties and relations among our thoughts (for instance, if we think it is raining, then we ought also to think that things outside will be wet) with the alethic properties and relations among the objects of our thought (namely, if it is raining, then, necessarily, things outside will be wet). To the extent that the (deontic) modal patterns in our thoughts reflect the actual (alethic) modal connections among the things we’re thinking about, we have grasped the truth. Notice that the correspondence can go only so far: subjective concepts are changeable, subject to further and further determination as they approximate ever more closely the objective concept they are intended to capture. The objective concept (for instance, what causation in the world really is) is not, we assume, subject to change: it is the stable ideal at which the series of subjective concepts of causation aims.

Hegel is an idealist, not in the sense that he thinks the world consists only of mental states; he is an idealist because both subjectivities and objectivity itself are constituted by the rich modal relations, respectively deontic and alethic, among the items of these realms. He is an idealist because the structure of being and the structure of thought are the same, albeit in different ‘keys’ (alethic vs deontic).

There is, of course, significant resistance to Brandom’s reading of Hegel, especially among those who emphasise the religious or spiritual dimension of Hegel’s thought. Brandom’s interpretation of Hegel’s God is deflationary:

God the Father is the sensuously clothed image of the norm-governed community synthesised by reciprocal recognitive attitudes (having the structure of trust) among self-conscious individuals.

Brandom also has difficulty explaining (away?) Hegel’s pronouncements about the teleology of world and the end of history, aspects of Hegel’s system that Brandom barely mentions.

Hegel’s revival in English-speaking lands started with social and ethical philosophy, where Hegel’s recognition of the essential sociality of humankind was an important corrective to the almost solipsistic individualism of enlightenment liberalism. The antimetaphysical readings of Hegel broke down further barriers to contemporary understanding by showing that Hegel need not be read as reviving an obsolete rationalistic onto-theology. Brandom’s work, in turn, demonstrates that reading Hegel can contribute to a deeper understanding in the area long central to Anglophone ‘analytic’ philosophy: the philosophy of language. By finding an ‘edifying semantics’ in Hegel, Brandom has positioned Hegel at the very heart of Anglophone philosophy.

Hegel is one of the greatest philosophers. As much as I sympathise with the non-metaphysical readings of Hegel, I do not believe one can ignore the onto-theology implicit in so much of his writing. Any historically accurate interpretation of Hegel must take that into account. But it is not what I find most inspiring about Hegel. What I value most in Hegel is his tremendous insight into the structure of philosophical problems. His dialectic, which so often poses a problem for interpreters, is, to my mind, fuelled by the insistence that no concept stands alone. The dialectic is the search for the broader context within which some target concept – whether it be a highly abstract and general concept such as being or a concept with a more specific application such as sense-certainty, work of art, or legal person – can best play its role in capturing the reality we live within. The target concept can only do its job well in the company of other concepts, which, in turn, lead us on to still others. These are not relations captured in formal logic. Time and again, when I turn to Hegel’s treatment of some philosophic topic, illumination emerges from his (admittedly often obscure) discussion. Unravelling his turgid prose turns out to be worth the effort, affording us glimpses of how things ‘hang together’ that others miss.