Can the disadvantages that disabled people often experience be attributed to intrinsic vulnerability, or do they result from social arrangements? This is a pressing question, both because of the global disability rights movement, and also because of the current COVID-19 pandemic.

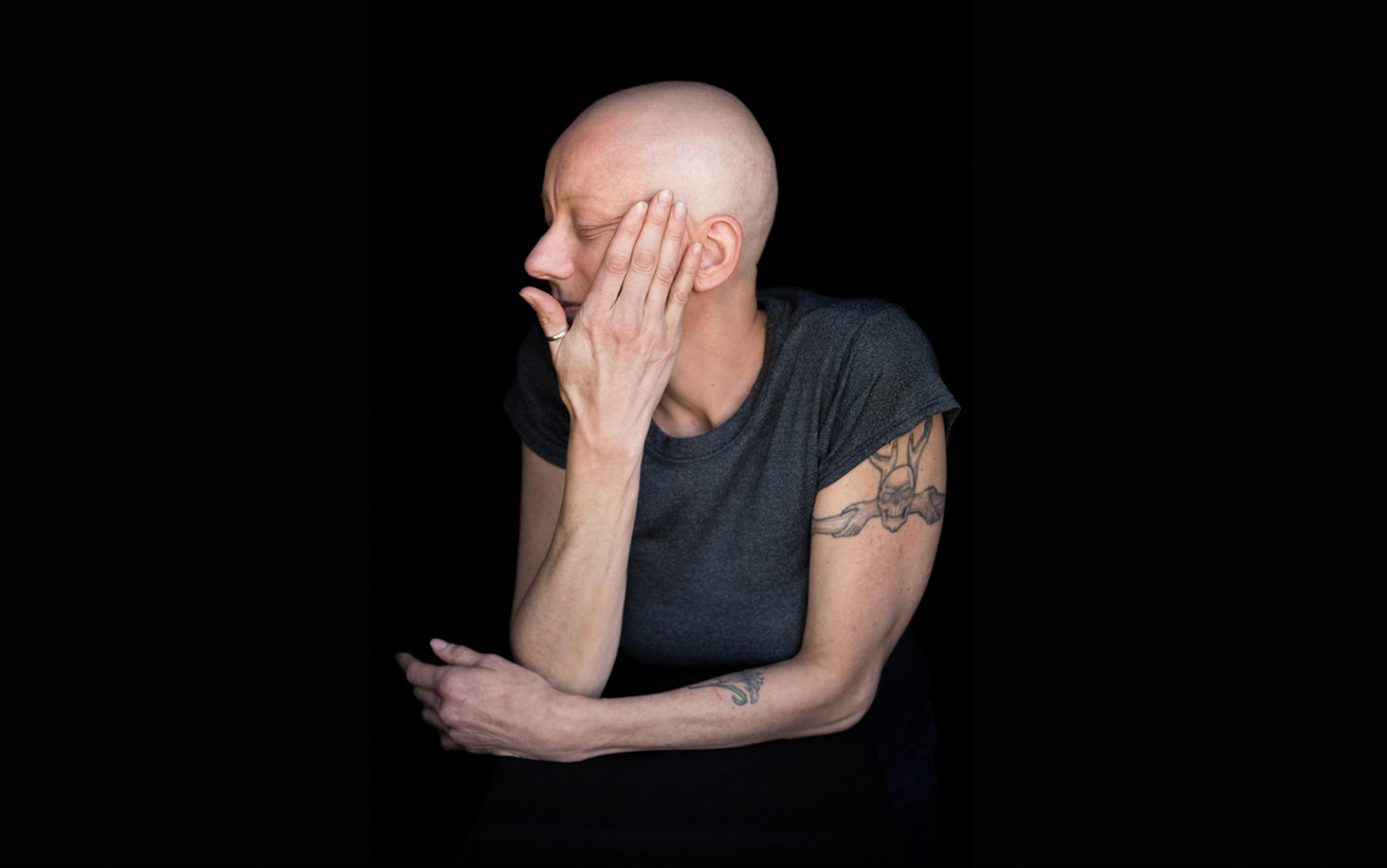

It’s also a very personal question for me. I was born with short stature (achondroplasia). Due to this rare genetic condition, I have had prolonged episodes of back problems, which have come with associated pain and immobility. In 1997, I was bed-bound for six months with sciatica. In 2008, I became paraplegic and spent 10 weeks in a spinal injury unit. Since then, I have used a wheelchair and had constant neuropathic pain. In 2021, I have been bed-bound for months with pain and restriction. I know that many health conditions, irrespective of social context, can be very disabling. In adulthood, I was diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which made sense of many aspects of my schooling. While it has not always been an obstacle, and may even have helped me ‘join the dots’, I would say it has also limited me as a scholar.

In Britain and other settings, there has been a public health debate regarding whether disabled people, particularly people with intellectual disabilities, should get priority in receiving the coronavirus vaccine. Most would agree that people at higher risk of getting ill or dying from this disease should jump to the front of this queue. People with Down’s syndrome, for example, have a very much higher risk of an adverse outcome from COVID-19. Those with cancer, or some respiratory conditions, or heart disease, or diabetes, also appear to be at greater risk, among others.

But some activists have been unhappy at being labelled as ‘vulnerable’. This is because they think this terminology reinforces negative ideas about invalidity or inferiority. The clunky phrases ‘clinically vulnerable’ (CV) or ‘clinically extremely vulnerable’ (CEV) have been coined to try to avoid this implication.

What’s this fuss really about? Does it say anything about the world we are trying to achieve? Perhaps most importantly, what can disability tell us about being human?

Since the 1970s, disability rights activists have undermined the equation that physical or mental limitation equals disadvantage. In the first version, limitations were a problem in themselves, but the bigger problem was society. Social factors are unjustly added to the limitation. But increasingly, disabled people have come to regard a health condition as neutral, and attribute to social factors any associated difficulties. In Britain, this has been achieved through the development of what has been labelled the ‘social model of disability’. Formalised in 1983 by the sociologist Michael Oliver, this states that people are disabled by society, not by their bodies. In other words, social and environmental barriers cause the problems that arise from different forms of embodiment. These barriers can be removed; failure to remove these barriers constitutes oppression, according to Oliver, or discrimination, to use the language of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, adopted by the United Nations in 2006.

In the United States, a similar argument has been made, but relying on what has been labelled the ‘minority group model’ of disability. In the civil rights tradition, this identifies a disadvantaged group – people with disabilities – and highlights the remedies that can enable this group to achieve equality. The Americans with Disabilities Act (1990), a pioneering piece of civil rights legislation, dismantles this discrimination.

Note that the social model and the minority group model are not the same, although they merge in much disability rights rhetoric. The first focuses on the ways in which people are disabled: in other words, the social barriers. The second focuses on the group as a whole that is oppressed: in other words, people with disabilities as an identity group. Both models minimise the contribution of impairment and illness to the lives of people who have disabilities.

Elizabeth Barnes, author of The Minority Body (2016), is a metaphysical philosopher who uses a very technical argument to conclude that disability constitutes a ‘Mere Difference’, rather than something that makes you worse off. If disabled people have a poorer quality of life, she says this is ultimately because of social factors and social judgments – a view consistent with the social model I’ve outlined. She defines ‘physical disability’ as what the disability rights movement classify as disabled. She thinks of disability as a cluster of physical factors, but in the end thinks that it is for the group to judge who counts as disabled and who does not, rather than the physical factors themselves.

She also says, in a response to criticisms, that ‘a major goal of my book was to argue that we can say both that some aspects of disability can be difficult, hard and painful in a way that would not be alleviated by social progress, and that disability is not, by itself, bad difference – and can in many cases be something which enriches and enhances the lives of disabled people.’ She feels that disabled people can find solidarity in how they cope with their difficult bodies.

The good things associated with disability do not balance or outweigh the bad things for me

I have experienced the truth of what Barnes writes. I can see how impairment can shape a person’s biography. For example, I cannot conceive of myself as anything other than short-statured or having a hyperactive brain. But I struggle with how she reconciles these views. If disability often involves difficult, hard and painful experiences, I do not understand how it could be a ‘Mere Difference’. I suspect that she thinks that other uniquely disability things compensate for what the philosophers Guy Kahane and Julian Savulescu call ‘the Detrimental Difference’. But I feel that there is an asymmetry. The good things associated with disability do not balance or outweigh the bad things for me. They are not commensurate. I can experience solidarity in many areas of my life, but I would prefer it to come without pain and restriction.

The disability rights movements in countries such as the UK and the US have often argued that disability is social, not intrinsic, as a form of identity politics. They have followed the pattern of feminist, gay and postcolonial social critics, and said the problem is society, not ourselves. If we reform society, our disadvantage would disappear. This may be true for gender, race and sexuality. But I do not think it is true of much disability. Remember here how different disability is. As well as trivial impairments such as a missing hand or a foot, it also encompasses profound autism and intellectual disability, and crippling depression, and the complications of multiple sclerosis (MS). Some of these are disadvantages in themselves: given the choice, no one would opt to have them. I want to say there is an innate disadvantage that does not go away, especially for the more significant forms of impairment.

Incidentally, identity politics, as the philosopher Nancy Fraser has said, leads us into dangerous byways. It stresses what divides us from others. It can easily turn into sectarianism. She argues that our goal should not be to put this group on a par with another group. Instead, our goal should be to say that this individual is on a par with another individual. We should seek to empower and respect individuals with disabilities, not disability groups – although the means by which individuals gain such respect may involve group action.

The people who would rather not be known as vulnerable are not untypical of disabled people in the political sphere. Many people prefer to speak in terms of diversity, not disability. This approach puts the onus on society to change and accept. It suggests that there’s nothing wrong with having an impairment or illness. These states of being are not intrinsically negative.

For example, for many years Deaf people have argued that they are a linguistic minority, not people with impaired hearing. If sign language was widely taught, and interpreters routinely provided, Deaf people would not be excluded. The failure of the UK prime minister’s COVID-19 press conferences to offer simultaneous sign language interpretation is symbolic of that.

People with mental health conditions often prefer to speak of themselves as those with ‘psychosocial disability’. Following the social model, this language implies that the barriers they face are entirely social, not intrinsic to the condition. Often, the language is of ‘users and survivors of the psychiatric system’, which puts the emphasis not on depression or schizophrenia, but on involuntary treatment and confinement in hospitals for the mentally ill. Influenced by the antipsychiatry movement, many highlight how no one has ever found a brain difference that explains schizophrenia and depression – unlike the research demonstrating how Parkinson’s disease or MS occur.

Let me change the subject for a moment, with a rather sombre question: what do Stive Vermaut, Tim Pauwels, Alessio Galletti, Frederiek Nolf, Rob Goris, Daan Myngheer, Eslam Nasser Zaki and Michael Goolaerts have in common? The sad answer is that they are all professional cyclists who have died from heart attacks in their 20s and 30s since 2004. I am not suggesting a common factor of drug abuse, though some might. Athletes – whether cyclists or golfers or soccer players or rugby players – all drive their bodies to the peak of achievement. They are superbly strong and fit. We know they are often injured, and sometimes have career-ending injuries. But we need to acknowledge that these most developed of human bodies are almost always damaged by their success. Everyone knows that boxing is bad for the brain. We are now learning that rugby also damages it with repeated injury and concussion, and there is a move to end heading the ball in soccer. Also, we can see that a golfer will very likely end up with a bad back; the endurance cyclist may do damage to their heart; a footballer may damage their knees. This is not simply bad luck: it is an almost inevitable consequence of pushing a body to the limit of fitness, and making your sport your profession.

In daily life, we ordinary folk may have less developed muscles and lower stamina, but we are always prone to coughs and colds, to strains and sprains, to cuts and bruises. As we pass the age of 50, nondisabled people become aware of our body and brain in a new way, as it starts to fail on us. We forget things, we limp, we put on weight, our muscles atrophy, our hair turns grey or falls out, we take longer to heal. Disabled people have those difficulties too but, for many of us, the aches and pains have been with us from the start. It is hard for people with lifelong disability not to be aware of our limitations. It is as if everyone catches up with us, and realises what it is to have back pain, or failing memory. For 20 years, I have been having daily conversations with my best friend about the pain that stops us sleeping: now I have this conversation with other friends too, for whom it is new.

The athletics example and the disability example and the example of our everyday lives point to an alternative, and I think preferable, way of thinking about human embodiment. I want to say: to be human is to be embodied, but this is to be weak, vulnerable and mortal. William Shakespeare has Lear say ‘unaccommodated man is no more but such a poor, bare, forked animal as thou art.’ He also has Hamlet refer to ‘the thousand natural shocks / that flesh is heir to’. Contrast this with René Descartes who, only a generation after Shakespeare, wrote ‘I think, therefore I am’ and seemed confident that the soul was separable from the machine-like body and would survive it. I believe in this case the poet knew better than the philosopher. While human cognition sets us apart from most other animals, human physicality means we are no different to any other living being. We might better say ‘I hurt, therefore I am’ or ‘I gradually lose abilities, therefore I am.’ Of course, philosophy has always engaged with mortality, particularly the existential philosophers such as Søren Kierkegaard and Martin Heidegger. But what about the morbidity or the vulnerability that everyone with a body and brain experiences?

To define someone as ‘disabled’ is to create a dichotomy where in fact we should recognise a continuum

There is a sometimes hidden strain of pessimistic materialism in Western philosophy that we need to attend to. Thirty years ago, I first encountered the heterodox Italian Marxist philologist Sebastiano Timpanaro, thanks to his collection On Materialism (1970). His writing alerted me to his forebears such as Lucretius, Friedrich Engels and Giacomo Leopardi. They each ask us to acknowledge that we cannot conquer nature – whether that be our own physical nature, or the nature that surrounds us.

Timpanaro was a prophet of environmental politics from the 1960s, warning against both nuclear holocaust but also human-made climate change and the relentless depredations by humans of Earth’s natural resources. My friend the historian David Forgacs points out how Timpanaro, after Leopardi, took the biomaterialist and ecomaterialist view that nature was in itself indifferent to humanity and could in fact be either destroyed by humans or could destroy them, unless they found ways of living in harmony with it.

Building on this, my own argument for disability rights does not rely on the familiar equation that because disability is to do with social barriers, not bodily deficits, therefore there is a moral and social duty to enable us to participate. Instead, I would argue: to be human is to experience bodily deficits. Everyone has this vulnerability in common. Therefore, make a world that can include everyone, regardless of their differences, as vulnerable to impairment and illness.

Please note, by this I am not saying ‘everyone is disabled’. People do not all experience very significant physical or mental limitations, nor the social discrimination associated with them. However, everyone is at risk of illnesses and impairments, and everyone experiences small limitations every day, impairments that tend to increase over time. The world does not divide into ‘disabled people’ and ‘nondisabled people’ – as all social scientists know. There are shades of grey, not black and white. To define someone as ‘disabled’, whether for reasons of social policy, statistics or political identity, is to create a dichotomy where in fact we should recognise a continuum. Disability is a contingent property. It is an artefact of the way it is measured, though that is not to say that it isn’t real, only to suggest that the line can be drawn in different places, and for different purposes.

I think it would be culturally, psychologically and philosophically more helpful to recognise our common human vulnerability, and then build a world that included this, acknowledged this, and prevented different exposure to vulnerability leading to social discrimination. The argument I am making here is close to what philosophers such as Eva Feder Kittay are saying, when they criticise John Rawls for failing to include disabled people or those who care for them in his contractarian theory. If, under the ‘veil of ignorance’, you imagine that you yourself might be among people who have significant impairments – or family members of people with these impairments – then you would be more likely to build a world in which these differences are not ignored but instead minimised by social arrangements.

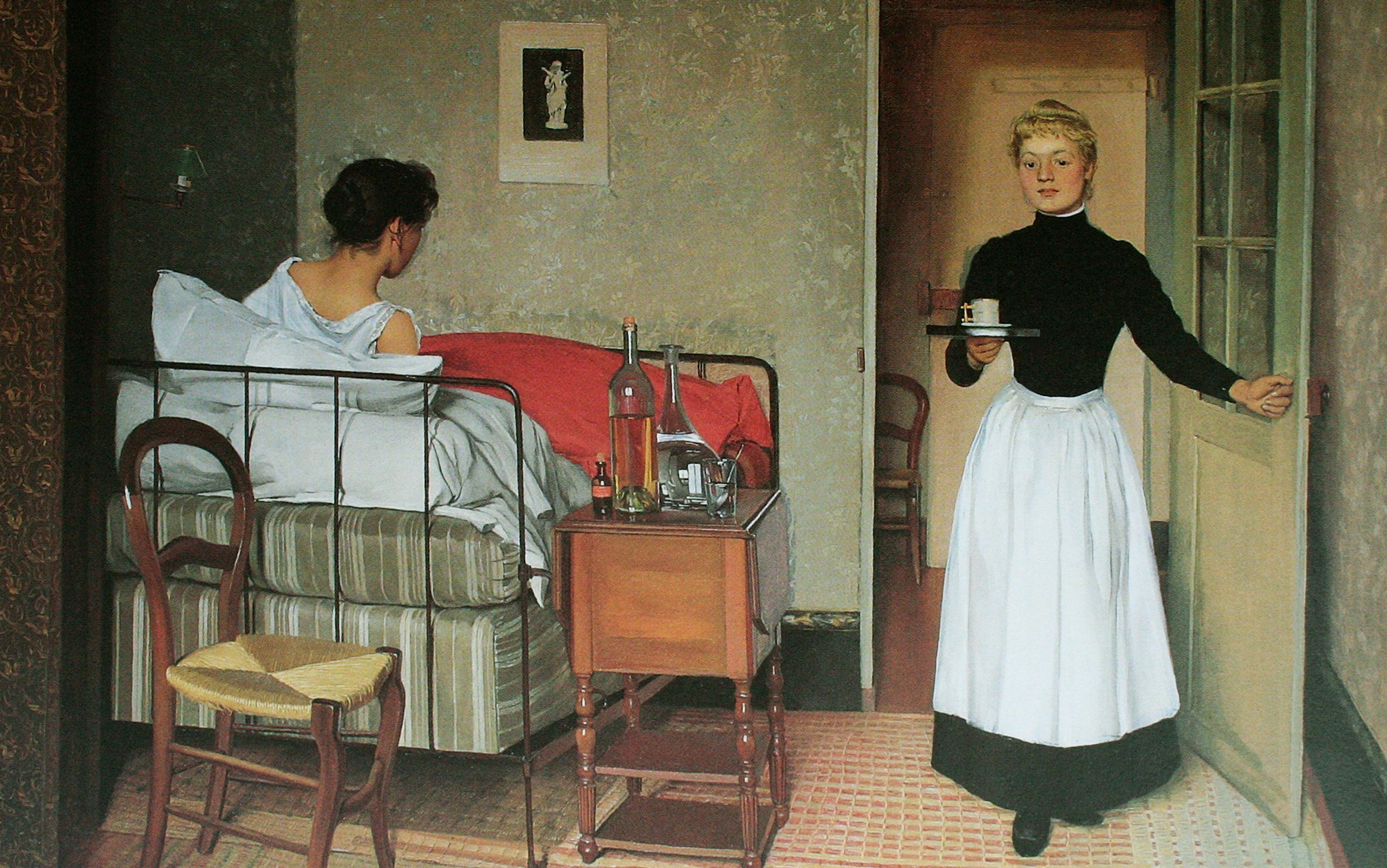

This approach may also lead us to be less individualist. If we are aware of common vulnerabilities and frailties, then we know we need others to survive. We might require help at any time, or all the time. We might think in terms of interdependence, not independence, much like the feminist ethics of care philosophers such as Joan Tronto, or the African philosophers discussed by Oche Onazi in his recent book, An African Path to Disability Justice (2019). The Ubuntu philosophy of John Mbiti, for example, says ‘I am because we are; and since we are, therefore I am.’ Even with barrier removal and better disability equality, disabled people will be much better off in a world in which everyone helps each other and talks to each other. As Kittay has argued, some disabled people will not benefit much from disability rights, but will benefit hugely from the support and caring solidarity of others.

The position I have held for the past 30 years is not popular with some disability rights activists. Yet it is what the vast majority of disabled people know to be true from their personal lives. It is also what emerges from all the qualitative and quantitative evidence about disability that I have seen. We are disabled by society, yes, and by our bodies and brains as well. We often have fewer choices than nondisabled people. On average, we have a narrower margin of health. It can be a real nuisance to be this divergent from the norm. And this does not mean that there might not be some real benefits too.

Disability justice demands removing social and cultural barriers, but also attending to mental and physical needs and limitations. We can now do so much about both, thanks to medicine, and architecture, and education, technological developments, and antidiscrimination law. But we cannot remove all barriers, and we cannot heal all problems there might be with bodies and minds.

This being so, there are good reasons to prefer not to have an illness or impairment. This will seem heresy to those who argue that we are simply ‘differently abled’. Prevention sometimes makes disabled people anxious. They argue: if I am equally valid as a person, why do we need to stop people becoming like me? Yet, even if we are living good lives ourselves, that does not mean illness or impairment are good, or even neutral. It is not self-hatred or eugenics to avail ourselves of vaccines, prenatal diagnosis, cochlear implants or other treatments. Even those people who themselves already have impairments are usually reluctant to have new impairments, or to have their existing impairments worsen. For example, I did not mind having restricted growth, but I wish I had not ended up in a wheelchair, or spent so many months bed-bound and in pain.

We can try to make the world more inclusive, while also taking folic acid to prevent a child from being born with spina bifida

The furore over the coronavirus vaccines is relevant. We think that people with learning disabilities should get a higher priority because they have a much bigger risk of dying than others. Why do they have this risk? For some people, it is because they live in congregate living facilities, and the virus spreads very quickly in a care home. For others, it is because they have a compromised immune system or respiratory difficulties, and the virus causes much more serious illness in them, if they contract it. The danger is both ‘clinically extreme vulnerability’ and social arrangements. Both biomedical and social dimensions contribute to the higher risk of falling ill or even dying.

We can do our best to remedy, or even prevent, illness and impairment, and still want to accept those who, despite these efforts, end up disabled. For example, when I chaired the working group that produced the Nuffield Council on Bioethics’ report on non-invasive prenatal testing, I made sure we wrote that we should welcome every child who comes into the world, whether they have a trisomy (an extra chromosome) or not. But this does not mean denying couples the right of screening and, if they want it, selective termination to avoid the birth of an affected child. We can try to make the world more inclusive, while also taking folic acid to prevent a child from being born with spina bifida.

Every human being has around 100 random mutations in their genome, which might be deleterious. We all carry four or five recessive conditions that could combine with those from a sexual partner to create a foetus with raised risk of a troubling disease. Genetic screening, even embryo selection, cannot remove the vast majority of the disability that life is vulnerable to. But it is a tool we can use.

Disability will always be with us, even though we can now do much to improve human health and reduce the risks. We are embodied beings, and impairment is the human condition. We have injuries and we develop diseases. If we are fortuitous, we live long lives and develop the impairments associated with ageing, such as macular degeneration and dementia. In the end, we all die.

I agree with Barnes and all those disability academics and activists who want to remove obstacles and build a more inclusive world. One of the positive lessons from the sad tragedy of COVID-19 is that digital communications can be more inclusive. As long as you can get access to a computer or tablet, online platforms can be barrier-free, and can connect people who were previously excluded by physical or communication barriers.

Even as we succeed in creating an inclusive world, we need to accept our limitations. Some people will never be able to live or work independently. All of us will grow weary and die. True inclusion is to value people equally, regardless of their abilities. Happiness comes from acceptance of frailties.