In late-1940s Jamaica, when my mother, Ethlyn Adams, was a teenager and began to think about courtships, she was summoned to the dining room by her father. He’d recently been promoted to inspector of police in the Jamaican constabulary, allegedly (in family lore) the island’s first black man to be appointed to such a senior position. Inspector Vivian Wellington Adams tapped his finger on the sandalwood dining table and warned his daughter: ‘I don’t want you bringing anyone into the house darker than this.’ My grandfather would brook no questioning of his version of the brown paper-bag test. He was a black man but he would not have answered to that description; he’d have considered it an insult.

Jamaica was a pigmentocracy – it still is – and a premium was placed on fair skin, a societal code that Frantz Fanon in Black Skin, White Masks (1952) calls an ‘epidermal schema’. Inspector Adams was a cinnamon-coloured brown man. His daughter Ethlyn, by her own estimation, as well as her family’s, ‘had good colour’, and no right-thinking person would allow their family-line to be contaminated by those of a darker hue. This, after all, was colonial Jamaica, at a time when the journalist and historian Vivian Durham observed cogently: ‘It was the ambition of every black Jamaican to be white.’

Ethlyn Adams, Colin Grant’s mother, in 1952

It is commonly agreed that race is a social construct. If, as sociologists such as Alondra Nelson tell us, there is more difference within groups than between groups – so that, as the child of dark-skinned Jamaican parents, I have more in common genetically with a red-haired Scot than a sub-Saharan African – then why do I still feel obliged to accept the primacy of race, and the notion that any distancing from those of my own phenotype is a betrayal? If my ornery old grandfather was still alive, I suspect he’d be enraged. Inspector Adams would have been more impressed by the attitude of Britain’s first prime minister of colour. Unlike the 1987 breakthrough, when four black and brown MPs – Diane Abbott, Keith Vaz, Bernie Grant and Paul Boateng: the first elected in modern times – emphasised the importance of their race and ethnicity, Rishi Sunak has dialled down his. Further, Sunak has signalled his allegiance to British Conservatives’ anti-immigrant, nativist tribe, such that his Hindu wristband and alignment with people of his complexion and diminished social capital among them are all but invisible.

Along with other high-profile politicians of colour in the Tory Party, Sunak has benefited from an elite private education and the kind of privileged connections historically associated with his white Tory peers. Winchester College proved as advantageous for Sunak as Eton did for Kwasi Kwarteng. Power trumps race: and, if the cost of maintaining the status quo is to admit a few conservative black and brown colleagues into their tribe, then that’s a price the Tories have deemed worth paying.

Unexpectedly, I seem to have gone the other way and become even more black as I’ve aged – especially through others’ perception of me – and that process appears to have accelerated since the murder of George Floyd and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement. But, and it’s a big but, it’s complicated.

While I enjoy the freedoms and vibrancy of black culture, I resist the tyrannies of the promotion and exclusive embrace of ‘Black’ – a descriptor, now capitalised by a growing number of papers (both Right- and Left-wing), journals and individuals, even though I never got the memo. What are we supposed to do about the perverse domain assumptions that underpin the adoption of an old racial taxonomy long past its sell-by date, as well as its triumphant inversion: the ambition to be Black fuelled by the old sentiment: ‘Fuck you, white people. You reject us? Nah, we reject you!’ But this notion of blackness is defined and limited by its opposition to whiteness, encouraging silos of separation. This surely highlights one of the central questions of blackness: what do you let go of, what and who do you allow to define you?

The Jamaican-born cultural theorist Stuart Hall expanded on Durham’s maxim in his posthumously published memoir Familiar Stranger (2017). Hall, whose snobbish mother especially prided herself on her relatively fair complexion, explained the structure and function of caste in Jamaica:

In order to locate an individual in a race/colour system, an optimum solution is to be able to call upon a code of differences which … can be read at a glance … In this strategy of social reading, the position of every individual becomes mappable.

My mother did not disappoint Inspector Adams. Ethlyn, I later learned, would go on to spurn the advances of Councillor Duval’s son, Donald. The councillor was highly regarded but his son was a bit on the dark side which disqualified him, as far as Ethlyn was concerned, from ever having the pleasure of stepping out with her. ‘You mad! I was really something to look at,’ says Ethlyn, ‘I thought I had better opportunities than that.’

A decade later, Ethlyn was bewildered when, arriving in the UK, it soon became apparent that British people were unaware of the nuances of colour, and couldn’t or wouldn’t distinguish between shades of black. My mother lamented that she was considered just another irksome darky in England. Back home, she had conflated colour with class, and would remind anyone who was minded to listen that she was not a poor, working-class sufferah, that she had, ‘never put basket ’pon my head go market’. Nonetheless, this new manner in which she was seen shifted the way that she perceived herself; she would not have used a phrase like ‘social capital’ but she recognised there was strength in the unity of the black church that invited a Caribbean migrant congregation of all hues, made unwelcome by the froideur of Britain’s pale churches.

Bageye, Colin Grant’s father, in 1972

Given her proclivity, it might seem perplexing that this Caribbean damsel plumbed for distress when she married Bageye, a man whose colour and class ought not to have made him much of a catch. In my racially sensitive youth, growing up in bigoted 1970s Luton, it was clear that Ethlyn had thankfully departed from the shadism script encouraging marriage that moved you up and out of your class and, losing pigment along the way, out of your colour. The ideal had been to become as light-skinned as possible while accepting that the border crossing fully into whiteness was a hard one, rarely, if ever, traversed. Such was the kind of pathology that locked families like Hall’s in the sort of prejudice that often masks self-loathing. Hall was bemused by his mother’s horror at the thought of her son (even though he was three shades darker than anyone else in their family) being lumped together with the great black mass of migrants. She hoped that Stuart, on a Rhodes scholarship at the University of Oxford, wouldn’t be mistaken for those ‘awful black people who are spoiling Britain with their presence; they should be driven off the pier with a big broom.’

Peculiarly, my father, too, expressed his dread of being too closely associated with black West Indians in Britain. At the time, in the 1970s, I assumed his distaste was ironic. But, at some level, there was a rationale behind his antipathy. Though in Britain he was reduced simply to ‘black’ along with all the other Caribbean migrant pioneers, it was a ‘different kind of black’ than he’d have answered to in his place of birth. Jamaica rendered him black black, five past midnight black; you couldn’t get much blacker. Whereas in Britain, so long as there were relatively few Caribbean people around – knowledgeable of the region’s hierarchical colour chart and who might unmask him as a lower-class black man – then Bageye could begin again; he’d have a blank canvas to define himself. Until, that is, Luton’s Labour council in their wisdom decided to move another Caribbean family right next door. Our blackness was instantly amplified. On the day of their arrival, Bageye hurried to the bedroom window and pulled back the curtain to watch the newcomers unpacking the van. He shook his head in disappointment: ‘Imagine this,’ said Bageye. ‘I travel 4,000 miles to get away from these people, and look who they put next door.’

My siblings and I celebrated the assimilationist trope of the ‘magical Negro’ expressed by Sidney Poitier

Britain also appeared to be a crucible of unhappiness for those West Indians who tried to hold on to the old code of pigmentocracy – and its associated superiority – from back home. From my perspective, as the child of Jamaicans in the 1970s, the previous generation’s plan of achieving social mobilisation through dilution of blackness seemed to have been binned. Black Beauty had been ushered in by the Black Power movement. The Jamaican version would be made manifest in the late 1970s by the rise of Bob Marley and Rastafari. Before then, in recognition of the influence of African American signifiers on our culture, we played the Afro-sporting Bob and Marcia’s ‘Young, Gifted and Black’ (1970) nonstop on our Blue Spot teak radiogram. And that’s a fact!

Alongside the allure of the ‘separate but equal’ (with whites) agenda promoted by Black Power activists, my siblings and I also celebrated the assimilationist trope of the ‘magical Negro’ expressed by Sidney Poitier in the interracial love story Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967). That Hollywood film seemed to answer in the affirmative the earlier headline in Picture Post: ‘Would You Let Your Daughter Marry A Negro?’ (1954). But in the decades that followed, with the escalation of race consciousness, such a question seemed presumptuous. By the 1970s, no one among the working-class West Indians in our orbit would have countenanced what they’d have considered an act of moral turpitude, self-harm and ‘race suicide’. They’d have argued that James Baldwin called it right in ‘The White Man’s Guilt’ (1965) when he wrote:

I have known many black men and women and black boys and girls who really believed that it was better to be white than black, whose lives were ruined or ended by this belief. And I, myself, carried the seeds of this destruction within me for a long time.

In any event, in the first flush of mass Caribbean migration, it was hardly an attractive proposition to marry a white English woman. Firstly because, so the story went, if such a woman went out with a black man, it was widely assumed that she’d hook up with any black man. Among these West Indian pioneers there was a strong allegiance to race – to preserve your blackness and not betray it. And, finally, everyone knew that the children of interracial unions were to be pitied. This received view was so commonly held and articulated that I was appalled if anyone mistook me for being ‘half caste’; I didn’t want to be pitied. Nonetheless, I always recoiled from the harsh judgments of West Indians on those former compatriots who foolishly thought interracial marriage would promote their offspring: ‘Every monkey t’ink him pickney white,’ they’d jest. ‘But the Englishman know different!’

It was a toxic and confusing time, especially for the second generation – now black Britons – who’d never set foot in the Caribbean and could not comprehend the hangover and cultural translocation of its ‘epidermal schema’. In my youth, interrogation of the vexed question of race and the lies that bind us mostly came courtesy of African Americans. I didn’t discover Hall, the Huntleys, the radical bookshop New Beacon Books, C L R James, the seminal study Staying Power (1984) of the black presence in Britain (confusingly written by a white Marxist historian), Darcus Howe and the Race Today crowd, till my 30s. Before then, I’d relied on my uncle Castus and a handful of African American thinkers – Ralph Ellison, Toni Morrison and Baldwin in particular – as my racial cartographers. Their North American experience seemed rawer, more visceral and threateningly existential; ours was an attenuated version. What did we really have to complain about? Let’s face it, we were not mauled by snarling Alsatians, pummelled by water-cannons, or menaced by gun-toting police with their fingers lightly nursing triggers.

‘To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a state of rage almost all the time,’ declared Baldwin in 1961. The same just wasn’t true of black people in the UK – or not quite; in the 1970s and ’80s, you could occasionally take a racial sabbatical. Notwithstanding the difference in what I perceived to be the intensity of blackness between black people in the US and the UK, there were points of intersection. Black migrants inhabited a psychic space that called to mind the ‘double consciousness’ identified by the African American author W E B Du Bois – a shuttling between two states of being, of having ‘two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body.’ And there were other similarities – conveyed at least in literature and the arts generally – in the successful strategies chosen to navigate the hostile white world: you could code-switch and dial down your blackness to the degree that it was not quite fully, but almost, undetectable. After all, if you didn’t transmit blackness, then it might not be received, right?

If you were smart, you could frame blackness as an exoskeleton you could put on and remove

In Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah’s satirical short story ‘The Finklestein 5’ (2016/18), the job-seeking African American protagonist Emmanuel, operating on a 10-point scale, realises that the disadvantage of his colour is such that ‘he wore a tie, wing-tipped shoes, and smiled constantly’ to dial down his blackness to 4.0. His approach would have resonated with the African American writer Brent Staples who in his memoir, Parallel Time: Growing Up in Black and White (1994), recalled that, as a student passing through affluent middle-class white neighbourhoods, he determinedly whistled Vivaldi to signal, with this shared cultural reference, that he did not pose a threat. All very wearying and tiresome, don’t you think? Not something you’d want to visit on your children. But clearly the present UK government is brimming with cabinet members who fully absorbed that lesson and have eagerly paid its price for the entry ticket to political power.

My early adult unsentimental education in blackness was primarily forged in the company of my rambunctious, mischievous and worldly-wise uncle Castus. He encouraged a belief that, if you were smart, you could frame blackness as an exoskeleton you could put on and remove whenever it suited you. In the company of black activists, you’d be just as badass as any badass brother number one (who, by the way, only slept with white chicks as revenge); in the presence of well-meaning white liberals you could Mau Mau the penitent flak-catching motherfuckers and they’d lap it up and come back for more. It did not, though, quite sit with the altar boy, head boy, Sidney Poitier-like unthreatening approximation to the ‘magical Negro’ in me.

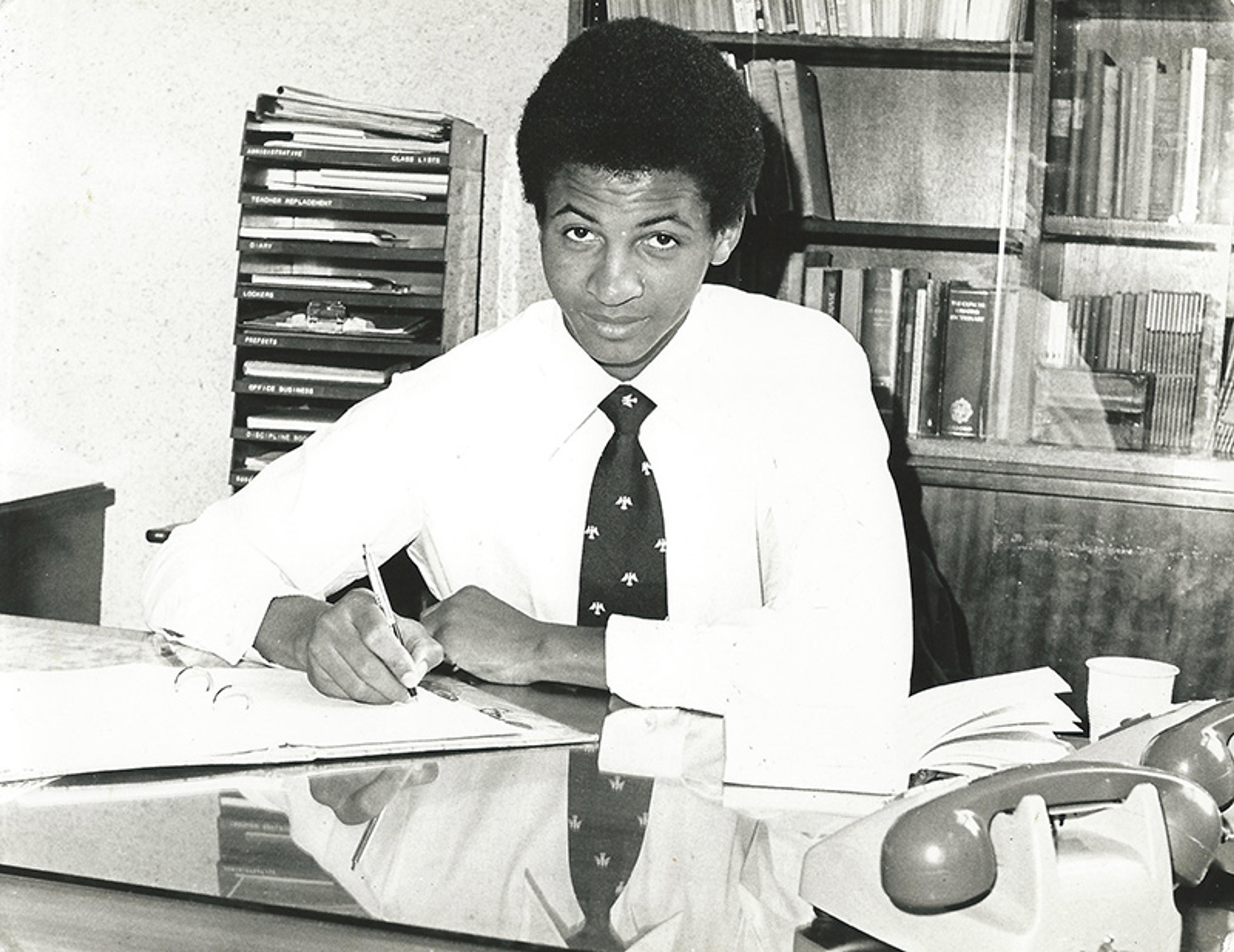

Colin Grant as head boy at St Columba’s College, in 1979

At the height of Black Lives Matter, myriad black people rocked uncle Castus’s strategy, as white educators, account managers, the BBC, publishers, art curators, the whole damn lot, rushed to plug the gaps – in their cultural sensitivity, in curating, programming, and the overall dissemination of benevolent funds to the deserving and not-so-deserving black folk. It’s the Wild West out there; their intentions may be sound but often their judgments, predicated on the optics rather than the quality of the person or the work, are suspect. At least they’re a bit speedier than the BBC manager who told me 30 years ago, after I went from freelance to staff, becoming the first black radio producer in the department: ‘We’ve done well with you, Colin. We’ll try for another in the summer.’

Back then in the 1990s, blackness in the UK was framed as a political description of folk with similar experiences of marginalisation. I confess a nostalgia for it now. It had broad appeal in Luton, especially among those migrants – Caribbean, African, and South Asian – who might have been suspicious of each other, who might even have felt estranged from each other, but were united in their loathing of the English.

And there were other unlikely allies. Although I had no thesis or research to back up my understanding, I knew instinctively that the Irish kids in Luton I hung out with – the Flynns, the O’Learys, the McLoughlins and the Dunns – were also not white, not really; they were looked down on and just as pitied as my West Indian bredren and sistren. They, too, had spent centuries under the heel of the English, were subjugated – were black by any other name – and suggested that, if we were tired of being black, we should try being Irish; then we’d really know what it was like to be a despised caste.

Later, I would learn that it was only at some point in the 18th century that the Irish had become white, and that it was prudent to distinguish the Irish in Ireland and the UK from Irish Americans. History showed, for instance, that Frederick Douglass, having escaped slavery in the US, was welcomed and championed in Dublin. But he counted Irish Americans among those enemies who did not recognise his right to freedom. Irish Americans had aligned themselves with the dominant ‘white’ tribe in the US. But in 1970s Britain, we cleaved to the Irish, and, indeed, when the Luton Irish team were down a man for the Sunday League football fixtures, I was delighted to be given a tap on the shoulder and to don the green and white stripes.

My Irish friends’ antipathy towards the English, and the promotion of a hierarchy of suffering where Irishness topped blackness, mostly amused me. Baldwin, though, was another matter. After a while, Brother Jimmy’s permanent, scorched-earth rage frightened me; he had the anger of the soul brother in a febrile time when the US is going up in flames, who fears rejection because he is not angry enough. I preferred the cool-seeming detachment of his fellow African American, Ralph Ellison, author of Invisible Man (1952). In Ellison’s writing, composed (I imagined) with an unlit pipe between his lips, a glass of fine whiskey caressed by his finely tapered fingers, and speaking with an erudite Southern cadence (from Oklahoma) into a new-fangled audio recorder that finessed his wisdom, he seemed to hover above all the nonsense and racial conflagrations. By contrast, reading Baldwin was like being trapped in an encounter with those disenchanted, disturbed-looking African students (permanent, mature students) who, like shipwrecked men, hung around Luton Tech in the 1980s giving the impression that they had several hand grenades wired to their vests and, fuck it, they didn’t care; they could pull the pins at any moment.

The framing of a life in black and white is reductive. Baldwin described the hollowing out of white Americans fixated on the black enemy within but, as I aged, I also felt the danger of me and my black bredren obsessing over white people. Honestly, after a while, I yearned to step off the carousel, to get out of dodge, move to Brighton; to get a job at the BBC where the focus was not on race but on exploring a life of the mind. It was a chance to escape from being corralled into blackness by ‘proud’ black people, well-meaning and not so well-meaning white people; a chance to ask yourself: apart from being black, what are you?

Riffing on this question with the filmmaker John Akomfrah, we agree that neither of us are ever going to claim that somehow we’ve managed to escape the legacies of blackness. Like me, Akomfrah believes that the trauma of blackness cannot be a badge of honour, ‘because nobody wants to hang on to shit that’s about causing you grief. It is not easy being black.’

My wife Jo Alderson and I wanted it easier for our children. In bringing up our kids in Brighton, whether subconsciously or not, we hoped to free them from certain tyrannies of blackness. But those tyrannies followed us to Brighton. In classrooms, there comes a time when pupils are distinguished from each other when – in the crunch year – the teacher brings up the thorny issue of race. Jazz, Maya and Toby were each forced, without any prior discussion (they never got the memo either), to play the role of race representative. The opportunity to wait in the wings – to bide their time, and come out only when they were happy with the script, or to discard the ‘received’ script and write their own – had gone.

The threat from being associated with blackness has not disappeared

As Jo is white, our children have also wrestled with notions of not being black, as well as being black. But in the past decade they have become blacker, as have I. They are black like me. Yet they reject the conception that I, in my youth, accepted; that blackness lies somewhere between a birthmark and a stain. Jazz, Maya and Toby argue that being black is something to embrace and yet not be fully defined by. If anything, the murder of Floyd and the upsurge of the Black Lives Matter movement reinforced that approach. Independently of any movement, they each undertook some deep soul-searching about who they were and how they identified themselves. Tantalisingly, into the mix of determining what it was to be black, they found that white arts commissioners, in the first flush of mass penitence, bent over blackwards to acknowledge and commission young creatives like them.

Each of them has a strong internal locus of control, and knows that their value and worth will outlast any showy, self-regarding fad of allyship – if that is what it proves to be. Culturally, they have been moving towards blackness, ever since they emerged from their mother’s womb. In recent years, the pace has quickened; it’s evident in their art, and how they carry themselves, embed themselves, and align their ideas in the work of art practitioners such as Erykah Badu, Romare Bearden, Roger Robinson, Gil Scott-Heron, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Claudia Rankine, Ellison and Baldwin. Irie!

Their incremental awakening finds resonance in Hall’s quiet epiphany. ‘In part because of modern jazz,’ he wrote in his memoir, ‘I gradually became aware of a new reservoir of feeling and identification opening up. I felt in touch with the slow-burn emergence of a new sort of black consciousness …’

It may be a good time to be black in the number of gigs coming their, and my, way, but there are forever two trains running – in opposite directions. The threat from being associated with blackness has not disappeared. Those same white editors who want to congratulate themselves on capitalising you as ‘Black’ despite your objections, find soulmates in employers who tremble when you do not show deference to them, and move subsequently to extinguish you. Both seek to box you in as ‘Black’ and are enraged by your ingratitude when you protest.

I can identify the precise moment when I became irredeemably ‘Black’, half-past-midnight black. On 4 January 2004, an unassuming envelope was pushed through the frontdoor letterbox of my home and fell onto the mat. The letter invited me, a long-serving radio producer, to a BBC disciplinary hearing (the first of four). I gleaned that it had something to do with an apparently disrespectful observation I’d made in a departmental meeting, when I challenged the new boss’s determination to knock down walls to make everything open plan; I’d likened the arrangement to a plantation with the overseer looking down on the enslaved. My alleged transgression was not a joke, my accusers suggested, but just one example of ‘a pattern of aggression’ and, as the first and subsequent hearings unfolded, it became clear to me that I was actually on trial for being tall and black.

There are degrees of jeopardy when it’s discovered, as suspected all along, that you really are black, a virulent Trojan Horse intent on burning down the master’s house, singing: ‘There is no more water to out the fire, let it burn!’ For a few months, while under investigation by the BBC, I had sleepless nights. But when the intense Kafkaesque interrogation came to an end, I was able to move to another department and avoid further scrutiny – at least for a while. Black people in the US, though, live a near-constant existential nightmare. From the moment my equivalent there wakes and steps outside his front door, he is conscious that unwelcome things may happen to him – violence or some other kind of bad outcome may head his way; he might not even be sure that he’s guaranteed to return home that evening. Notwithstanding the attacks I have weathered because of my colour, I am aware that, 40 years on from leaving the Luton council estate, I am now fully middle class, and have not been subjected to the daily humiliation and prejudices of those not as privileged as me.

Colour does not privilege compassion; the black and brown experts on the panel might have been green

It’s also difficult – absurd even – to argue that one’s progress through British society has been hampered when you have been head boy at a junior and senior school (where the only black pupils were my brother and I), a medical student, a BBC producer and broadcaster, and are invited to write for respected outfits such as the TLS, Granta and Aeon. And yet, holding the BBC’s record for the highest number of disciplinary hearings in the corporation’s history suggests the notion of the exceptional ‘magical Negro’ works only up to a point – before you default to irksome darky status. Get this: if goody-two-shoes Grant can be investigated essentially for being black, then pity the poor bugger who comes after him, whose CV does not suggest that, apart from the colour of his skin, he is just like his interrogators.

Colin Grant outside Bush House, Aldwych, the former home of the BBC World Service in London, in 2015

But hold on. Institutionalised racism has been overstated, a UK government-sponsored inquiry suggested in 2021. Claiming that it was a dominant feature in British society succeeded only in ‘alienating the decent centre ground’, according to the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities, set up after the Black Lives Matter protests. The government has since rebuffed criticism that its conclusions were wrong, highlighting that all but one of the commissioners of the report were people of colour. Clearly colour does not privilege compassion or understanding; the black and brown experts on the panel might as well have been green; it didn’t matter.

What mattered was that these decision-making people of colour had found another tribe – like those black and brown members of Sunak’s cabinet – that trumped blackness; it’s a tribe coalesced around class; it’s always class, stupid. Hall would have told you so, and Baldwin also.

Never mind shoving those awful black people off a pier with a big broom; pack them on to a plane bound for Rwanda. Maybe you think you’re the right kind of black – a Suella Braverman, Nadhim Zahawi, Priti Patel, Kemi Badenoch kind of black, whose signalling allegiance to whiteness in the UK’s purposefully opaque race/colour system can be ‘read at a glance’. Having willingly paid the price of the ticket, you probably feel you’re safe. But let me remind you of brother Jimmy Baldwin’s warning. It was true more than 50 years ago when he wrote in support of a demonised Angela Davis, and it’s true today: ‘If they take you in the morning, they will be coming for us that night.’ You may think otherwise – that you are third-generation Caribbean, Irish, Pole, Pakistani – but, come crunch time, you may just find that you’re ‘Black’ or at best, black like me.

Colin Grant’s latest book ‘I’m Black So You Don’t Have to Be: A Memoir in Eight Lives’ is available now from Penguin.