Current technology allows for radical memory enhancement: smartphones can record (and transcribe) every conversation, and wearable cameras can capture hours of first-person audiovisual recording. We have excellent reason to record much more of our lives than we already do and thereby enhance our memory radically.

The case is simple: our memory is immensely valuable to us, and we already record much of our lives using video and photography, messenger logs and voice messages. These records are valuable to us in significant part because they enhance our memory and thereby promote its value. Recording those parts of our lives that we do not yet record would possess the same kind of value. Properly appreciated, this gives us reason to record much more (and create so-called lifelogs): nearly all of our conversations, everyday life and, in general, as many experiences as feasible.

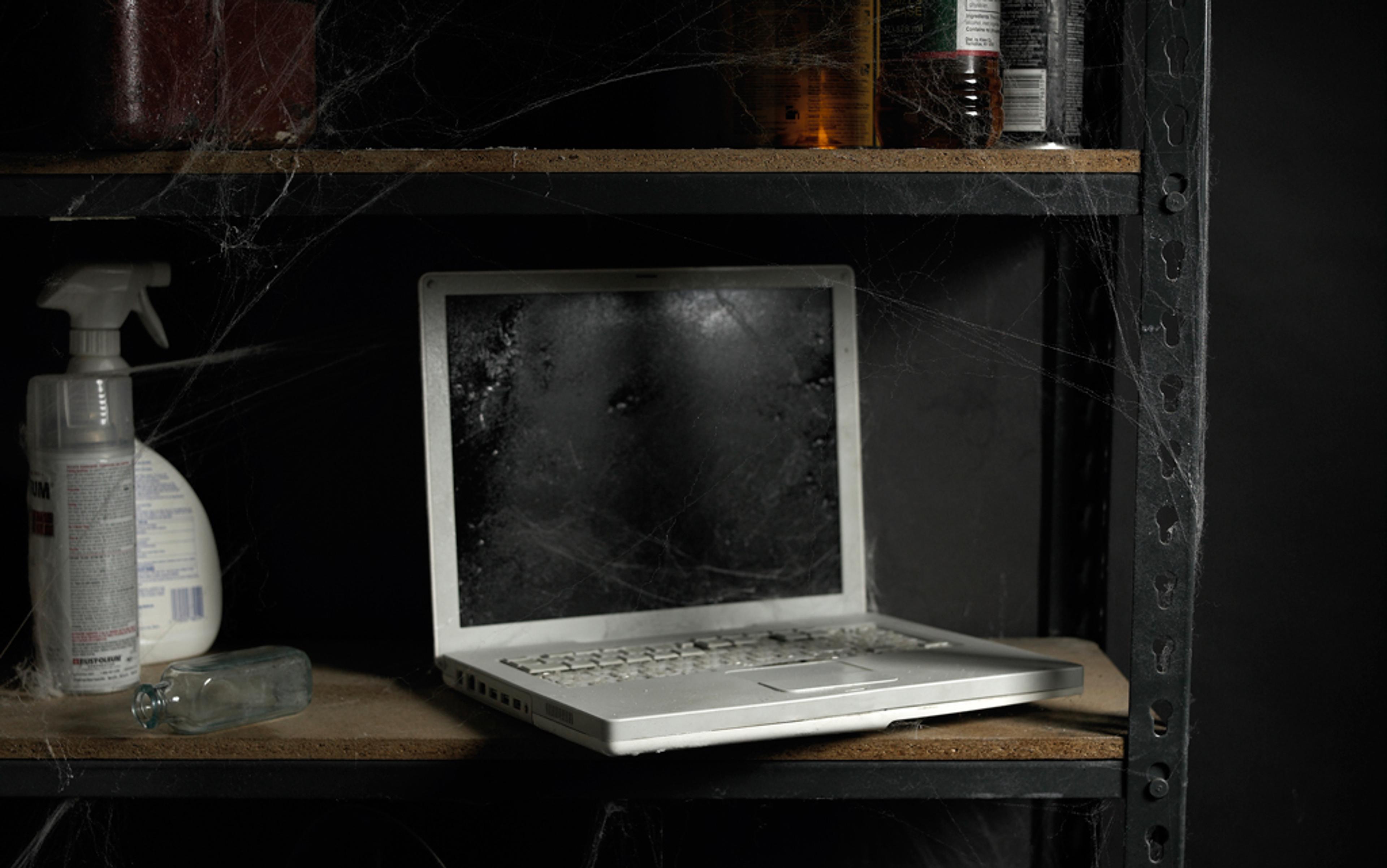

But this thesis faces important concerns, including worries about technological feasibility. Creating these records should ideally function without additional effort: they should be frictionless like messenger logs or the fictional technology in the Black Mirror episode ‘The Entire History of You’ (2011). A lifetime of records would take a lifetime to revisit in real time (with long stretches of little intrinsic interest). But we could revisit parts by searching by timestamp or tags, and the content of records could be automatically analysed, and software could generate transcripts and best-of cuts. Audiologs, transcripts and lower-resolution footage wouldn’t create storage problems, either. Objections from privacy and adverse psychological effects appear more significant. I will address these objections below, and will end with a plea: try recording almost everything before you rule it out.

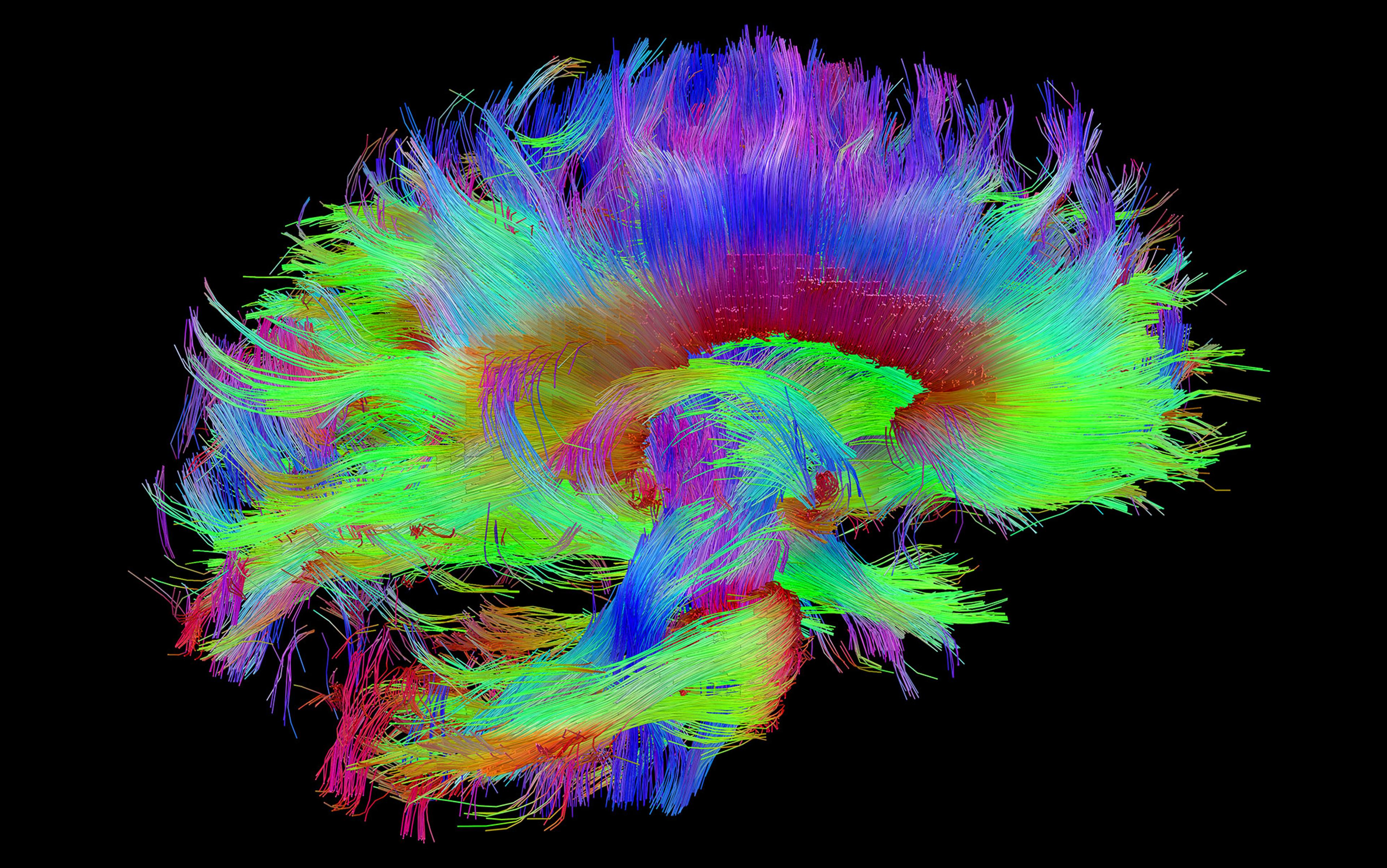

Why is our memory so valuable to us? Beyond its obvious role for survival, let us focus on three key aspects: first, we take pleasure in remembering and reminiscing. Second, our memories help us understand ourselves, others and our place in the world. Third, our memories play a crucial role for personal identity: who we are as persons is determined by our memories. These constitute our selves, so you are literally made, in part, of your memories. Our memories are valuable because they help make us who we are as individuals.

A richer and deeper memory can quite literally turn you into a richer and deeper person

The exact role memory plays for personal identity is subject to a philosophical debate going back at least to John Locke in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689), who discussed the idea that a person remembering their previous experiences is both necessary and sufficient for that person’s identity through time. Many versions of the idea that personal identity requires some kind of psychological continuity between a person at an earlier time and a later time have since been developed. Building on this rich tradition – represented more recently by Alasdair MacIntyre, Charles Taylor, Derek Parfit and others – Marya Schechtman in ‘The Narrative Self’ (2011) argues that our selves are constituted by an autobiographical narrative formed from memories of our past experiences. On Schechtman’s view, who we are is partly determined by our autobiographical narrative and the memories on which this narrative builds; see also Dorthe Berntsen and David C Rubin’s Understanding Autobiographical Memory (2012).

Given such views, it seems that a richer and deeper memory can quite literally turn you into a richer and deeper person. Richer and deeper memories appear to enhance your individuality: a thin and shallow autobiographical narrative appears to lead to a less substantial self, whereas a rich, detailed and deep autobiographical narrative appears to lead to a more substantial self. Assuming the latter is more desirable, a richer and deeper autobiographical narrative and the acquisition of memories that constitute it are more desirable.

Consider current memory enhancement practices: why do we keep chatlogs, take pictures or write diaries at all? Of course reasons are plentiful: journaling can serve reflection; picture-taking has an artistic component; habit and device presets may play a role, etc. But we clearly value our records in large part because they enhance our memory. Our memory is valuable and this value is promoted by the records that enhance it.

Records enhance our memory and thereby promote the three kinds of value just identified: we enjoy reminiscing by looking at our pictures and videos, and we understand ourselves and others better by revisiting chatlogs, social media posts and journal entries (moreover, records can – for better or for worse – be shared directly with others). But our records also enhance our autobiographical memories and thus help determine who we are as persons, allowing us to have richer personalities and a more complex individuality.

A radical way to support this idea comes from the extended mind hypothesis first put forward by Andy Clark and David Chalmers in 1998, according to which external devices and the data they store can literally be part of our mind. According to this hypothesis, we extend our minds by using parts of our environment that can function for us in the way that parts of our brain do. In this vein, Richard Heersmink argues in ‘Distributed Selves’ (2016) that external information can literally constitute (autobiographical) memory and thus help determine who we are as persons.

It may one day become possible to integrate records with our cognition as we do with biological memories

But the extended mind thesis is disputed, and it can be questioned whether external records themselves could indeed be memories: unlike records, memories have an autonomous character (memories come to mind, records normally don’t), a sense of intimate ownership, cognitive and emotional integration, and encompass all kinds of experiences, including moods, thoughts and whole conscious episodes.

Through technology such as mind-machine interfaces, it may one day become possible to integrate records with our cognition as we do with biological memories, but today we can rely on a less radical alternative: external information can fail to constitute autobiographical memory proper but nonetheless help to inform and enhance our diachronic selves, just as autobiographical memory does. What matters about autobiographical memory vis-à-vis determining our selves seems to be our ability to construct and recount pieces of autobiography (for example, when wondering who we are or were, and how we ended up where we are). External records can enhance this ability and tie it more closely to reality, even if they don’t count as memories proper.

Indeed, external records can be far more reliable in supplementing autobiographical narratives than relying on biological memories that can often be checked only against themselves. These are systematically distorted when recalled, and the act of recalling changes them further. External memory prompts aren’t subject to this and could tether us more reliably to reality than biological, subjective memories can.

Just as memory disorders can diminish our personalities in undesirable ways, therapeutic memory enhancements through audiovisual records can help to restore them; see Aiden R Doherty et al’s paper ‘Wearable Cameras in Health’ (2013) and J Adam Carter and Richard Heersmink’s paper ‘The Philosophy of Memory Technologies’ (2017). Under ordinary conditions too, it seems that external memory records can help healthy individuals to develop richer and deeper selves. So, memory enhancement through records is valuable because it helps create pleasurable experiences of reminiscence and increases our understanding of ourselves and others, but also because it literally turns us into richer and deeper individuals, either because records themselves are external memories that constitute richer autobiographical narratives, or because their memory-like nature supports the continued creation of such a narrative. Insofar as becoming richer and deeper individuals is desirable, memory enhancement through records is also desirable.

So far, I have argued for the value of records that most of us already create daily, based on the value of the memory that they enhance. But, when properly appreciated, it seems that the reasons that motivate these memory-enhancement practices should motivate us to record a lot more.

Consider conversations and other experiences we don’t normally record, such as a conversation with a friend: if every conversation generated a chatlog (automatically transcribed by a digital device) or took the form of letters, you might come to cherish these like you cherish your biological memory. Searchability of such records is key, but we know that current technology allows this already. There are so many conversations we could record but don’t. More seems to be more here. We already record much, but significant parts of our lives remain fleeting (so many conversations, unexpected events, and much of everyday life including periods seemingly without remarkable events).

Most people already record some noteworthy events (audiovisually or through writing). But remembering and recording unexpected, spontaneous but notable, mundane or recurring events is often just as valuable in retrospect. And even where single events aren’t obviously worth recording, many of them together form a significant part of our experience and contribute to who we are, just as painful or otherwise negative experiences can. Thus, even the value of records that aren’t pleasurable seems evident since they let us remember and understand ourselves better, even if we rarely revisit them.

Recording social interaction allows reminiscing about it more accurately, improving our understanding of what was said and our picture of ourselves and others. Consider the last worthwhile conversation you didn’t record – wouldn’t it be good to have such a record, just in case? And if you had such a record, wouldn’t you want to keep it? Granted, most current (audiovisual) records miss much of our experiences, including inner speech, conscious experiences and emotions. But I am neither arguing that extensive audiovisual records should replace biological memories or other techniques such as journaling, nor that current recording technology can capture everything worth remembering.

Imagine all the pictures you’ve ever taken and every message were deleted – how would you feel?

We already record much, you might say, why then record even more? Recording more might be valuable, but should we record everything? There is a risk of a status quo bias here. It is, however, unlikely that we have chanced upon the sweet spot of recording just the right amount. Answering what this is presumably requires personal reflection and experimenting with the technology, to determine which records one values, and decide what kind of person one wants to be.

Playful imagination can help assess alternatives to our present way of life. Have you ever wished for perfect recall? Lifelogs are almost like this, although voluntary, accurate and restricted to recordable sensory modalities. Our present recording practices indicate how much we value memory enhancement. Imagine all the pictures you have ever taken and every logged message were deleted – how would you feel and why? I would feel devastated, like having lost a part of me and a prized basis of understanding myself and others in my life. Likewise, we can imagine already possessing extensive records (of every conversation we ever had, say), then losing many of them to end up with what we in fact possess. I imagine this as a comparable loss.

We can reflect on our relationship to our enhanced counterparts by thinking about people with memory disorders who use lifelogs for therapeutic purposes. Our present recording practice isn’t only more desirable than the situation of people with impaired memory, but also better than that of past people who lacked the ability to create written or audiovisual records. From the imagined perspective of people with access to a universal, friction-free lifelog, our situation would likely appear comparably less desirable. This vision from the future gives us reason to pursue more extensive recording: more will be more!

Not only would we benefit from recording more, our family and future generations could too. Diaries and letters already allow glimpses into the lives of our ancestors. But imagine how much better we could understand them had they (say, your great-grandparents, or perhaps Ludwig Wittgenstein) recorded everything! As it is, we don’t possess a single audio recording of Wittgenstein’s voice.

You might also want to allow posteriority access to deadbots: language models trained on records of the dead to simulate responses their originators would have given. These might become uncannily life-like if trained on sufficient data – whether that would be desirable remains an open question; for a discussion, see Tomasz Hollanek and Katarzyna Nowaczyk-Basińska’s paper ‘Griefbots, Deadbots, Postmortem Avatars’ (2024). For instance, some philosophers continue teaching chatbots to impersonate their predecessors.

Finally, a highly speculative possibility: digital immortality. Could collecting comprehensive data about someone lead, one day, to a reconstruction of that person? This idea faces vexing questions about personal identity and the underlying causes of consciousness, not to mention the morality of undertaking such a reconstruction; for a discussion, see Dan Simmons’s novel Hyperion (1989) which features a ‘cybrid’ (a human-AI hybrid) with the personality of John Keats, as well as Paul Smart’s essay ‘Predicting Me’ (2021).

Given the preceding argument, memory enhancement through ubiquitous recording possesses significant value that any counterargument has to overcome: merely raising problems does not suffice to rule it out, though – a point illustrated by Plato’s Phaedrus, in which Socrates laments the negative effect of writing on biological memory. Nevertheless, we must discuss two serious challenges that could significantly constrain what we may record.

The first concerns privacy and data autonomy. People have a presumptive right to privacy and at least some control over what data about them is collected. In most cases, consent must be acquired. Sometimes this is straightforward. Many allow people they trust to record much, and might become more eager to consent once they appreciate the value of extensive recording. Still, many will not ever want to be recorded. The resulting gaps in our records could partially be filled by journaling but, as with non-recordable experiences, sometimes we’ll have only our biological memory to go back to.

But both accidental and intentional leaks (such as in revenge porn) remain a threat exacerbated by extensive recording practices. Powerful bad actors are another. Tech companies and governments have interests in records that often conflict with those of the general public. When Siri’s co-creator Tom Gruber praises AI-assisted memory enhancement, we should be wary, and the prospect of a police state with access to data on everything we’ve ever done should make us think carefully before proceeding down this path.

We should enable people to enhance their memories safely and responsibly

We could consider a less privacy-friendly argument. If records partially constitute ourselves, prohibiting those required for deeper personal narratives infringes on the very core of our being and forces us to remain shallower than we could be. We would not restrict people with biological super-memories or excessive journal writers, and there is no prohibition on turning oneself into such a person. Analogously, if recording technology can constitute someone’s self, sanctioning it may appear an objectionable infringement upon our ability to self-constitute. Conceivably, privacy concerns could require the suppression of natural memory, but they don’t. One might think memory enhancement should be treated likewise. Evidently, this argument must address the fact that external memories are easier to share and subject to less distortion than biological ones.

Answering these challenges requires much more work but, given the value of extensive records, I believe that concerns about privacy and autonomy should be addressed through technological means (like open-source software, encryption, automatic acquisition of consent, data deletion if desired) and legal means (like robust privacy rights and regulation of bad actors). Given my positive argument above, powerful reasons exist to implement such safeguards. We should enable people to enhance their memories safely and responsibly.

Another important challenge is that recording everything could conceivably have negative psychological effects. Knowing such records to be available, why would we bother to remember anything for ourselves? Through lack of use, our biological memory might well atrophy (the use of digital maps and navigation appears to be having this effect on our ability to navigate our environs unaided). Extensive records might cause us to live in the past, become less open to new experiences, less able to cope with loss; being constantly recorded could promote self-censorship.

On the other hand, conceivable positive effects include higher accountability and demands on one’s own behaviour; recording everything by default might allow us to live in the moment more; instead of straining our social relationships, it could make us more understanding of each other. We shouldn’t rely on speculation here – plenty of which exists in both sci-fi and in research like Björn Lundgren’s paper ‘Against AI-improved Personal Memory’ (2021) – but current empirical results appear ambiguous and don’t assess widespread use of lifelogs. Negative effects presumably vary individually, and it hasn’t been shown that they outweigh the value of lifelogs.

Even in light of the previous challenges, I believe that we have compelling reasons to at least experiment with recording almost everything. Philosophy and empirical research can go only so far in establishing a technology’s consequences and desirability. However compelling the arguments, it seems plausible that the decision to radically enhance one’s memory must involve an element of individual preference. So, what kind of person with what kind of (extended) memory and recording practice would you like to be? Arguments and contemplation can help you think this through, but ultimately you must try for yourself.