My mother was born in July 1944 in Holland, 10 months before the Netherlands was liberated by Allied soldiers. Decades later, the long shadow of the war extends to me through stories that my mother tells, drawn from the novels, memoirs and family lore she collects about Nazi-occupied Holland. She’s sure that her own early memories include the drumbeat sound of soldiers’ boots on the ground. Her older siblings suggest, gently, that these recollections more likely reflect the accumulation of repeated stories. What strikes me, overhearing these conversations, is the ambiguous line between memories and stories, especially when it comes to formative moments in childhood.

In the early aftermath of the war, the French philosophers Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre used the term ‘existential’ to mark a radically first-person approach to history. Instead of the seemingly implacable nature of an event in time, these existentialists pointed to the subjective meaning that such events hold. I need to choose the circumstances of my birth, Sartre explained in Being and Nothingness (1943), even though this seems like a choice that far exceeds any option available to me. When I teach Beauvoir and Sartre in my philosophy classroom, I like to read this line aloud and then pause, allowing for a few beats of scandalised silence. To choose my own birth? What counts as ‘my birth’ at all?

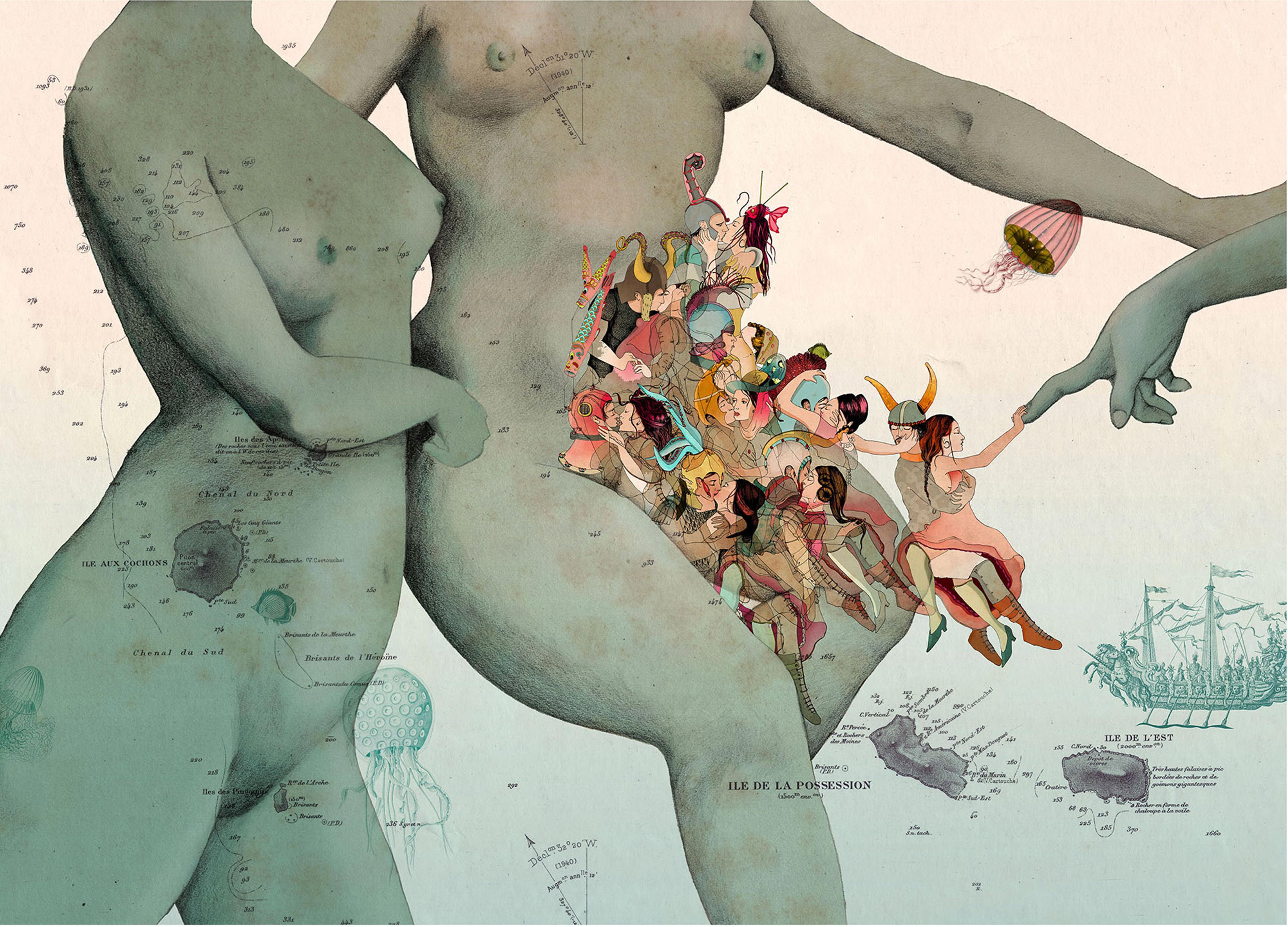

This provocation expressed the ‘existentialist offensive’ that Beauvoir and Sartre were embarking on during the mid-1940s. With such declarations, they made the case for a philosophy that solicits freedom, a corrective to our sense of limits. Rather than resignation about what I cannot change or naivety about changing everything, I am drawn into what Beauvoir later described in The Second Sex (1949) as the drama of existence.

One way to choose my birth has become more available in recent years, thanks to insights from evolutionary science. Babies born just a few months after my mother, during the harsh famine that began in October 1944, became part of a crucial data set for scientists studying the interplay of genetics with experience. My grandfather was in a German prison camp during those months, betrayed by a nephew for his work in the Dutch resistance. But as the famine broke out, my grandmother and her four children, including the infant who became my mother, travelled a few kilometres from their Friesian village to the nearby farm of relatives. However, families who lived in ‘famine cities’ such as Rotterdam, Amsterdam and Utrecht underwent specific and traceable changes in diet; those individuals and their babies in utero could thus serve as examples for what scientists now call ‘epigenetics’.

‘Epi’-genetics refers to changes that are not inherited through DNA but rather result from interactions between genetic processes and experience. A research project called the Dutch Hunger Winter Study used the 1944 famine in the Netherlands as a natural experiment. Concluding that exposure to specific conditions such as caloric restriction can be linked to epigenetic changes, expressed in symptoms such as tumours, scientists said that data from the last months of the war revealed the importance of how, when and under what conditions a person is born. Like the first generation of those caught up in the famine, the second generation also gave birth to low-weight children, demonstrating the inheritance of traits at the cellular and molecular level operating apart from DNA.

Epigenetics serves as a bridge between genotype (literally, the genes) and phenotype (the way the genes are expressed), accounting for the impact of time. In the context of epigenetics, contingencies are inseparable from biological development: what I experienced in utero or during early childhood can be key to processes such as the repression or activation of DNA. Evolutionary scientists refer to development as ‘ontogeny’: even identical twins with the same DNA are different, epigenetically, because each person is embodied, embedded in relations or situations, in distinct and unpredictable ways.

I’ve come to love this term ontogeny because it brings together, in one helpful word, the flux of becoming that scientists as well as existentialists seek to understand. By rallying readers with their slogan ‘existence precedes essence’, Beauvoir and Sartre were drawing attention to the utterly singular way in which we each become the selves that we are, with our own memories, stories and storytelling habits.

This account of meaning-making is part of how evolutionary researchers track the emergence of our own species, Homo sapiens, over time. It might seem like acknowledging our animality is far from existentialist philosophy but, in the context of contemporary writings on evolution, it comes right to its heart. Our longing for existential meaning, as the anthropologist Augustín Fuentes explains in The Creative Spark (2017), is a key component of our development as a species. To consider capacities such as choosing or adjudicating meaning, according to him, is to reflect on the long arc of becoming human, a trajectory perhaps best described as the process of hominisation. On this account, our evolutionary emergence as a species is inseparable from the story of earlier, now-extinct species, in particular Homo erectus, the animal who roamed in and also far beyond Africa. It is Homo erectus who created fire and learned how to hunt, inhabiting and shaping their environments in ways that Fuentes calls ‘niche construction’. They also developed larger brains than their ancestors and, crucially, experienced longer phases of ontogeny or childhood development. These details are what existentialists include under the term ‘facticity’: the physiologies we’re born into, the concrete ways in which we inhabit our ecological spaces.

My actions reshape me, how I reach out to the future, in a kind of existential feedback loop

Choosing my birth, I’ve come to believe, should involve learning more about our phylogenetic past. ‘Hominisation’, the name for how we as modern humans joined a broader and diverse species family, compels us to reflect on what it means to be a member of our species. Fuentes points out, for example, that modern humans are closer in kinship to chimps and gorillas than to orangutans, an important claim when it comes to scrutinising our contemporaries on the planet for insights into who or why we are. (If chimps are close kin, then primatologists who study the social behaviour of chimpanzees can help us make sense of our primate tendencies. The fact that we share with chimps an all-engrossing sociality, for example, draws attention to the myriad ways in which we groom, care for, collaborate and build trust with each other.)

Of course, we’re not chimps or gorillas, and the study of our phylogeny is replete with impassioned discussions over the shifting boundaries of speciation. Even the timeline of hominisation is a matter for wide-ranging scientific enquiry and debate. Depending upon the school of thought, the hominin family, made up of us and our extinct cousins, might extend back 4 million, 6 million or even 9 million years. Because of the importance of bipedalism, developing into upright walking apes prior to the time of Homo erectus is a key origin story for becoming human. The question of when, precisely, we became ‘us’ is a methodological one for scientists because it begs certain presuppositions about the evidentiary artefacts left behind by our long-gone ancestors. Are the fossils that indicate bipedal, two-legged movement the sign of human-hood? Or are signs of meaning-making behaviour, such as cave art or burying one’s dead, better expressions of human animality because they point to symbolic, complex communication?

In 1944, the year of my mother’s birth, Beauvoir’s Pyrrhus and Cineas was published, in which essay she declared: ‘I am not a thing, but a project.’ This claim is at first glance a descriptive one, pointing out that my actions create meanings that are not established in advance. But the claim is more than that. These actions, in turn, reshape me, how I reach out to the future, and even the world around me, in a kind of existential feedback loop. Every end or existential goal is a point of departure.

As a scientific resource for thinking about what ‘has to be’, evolution has long posed an existential risk, tempting us to relate to ourselves as things rather than as projects. Charles Darwin himself was aware of how readily we might misunderstand evolution as an account of essences, instead of differentiation-over-time. In a footnote that he appended to the third edition of On the Origin of Species in 1861, Darwin warned readers against attributing causality to ‘Nature’: the term Nature, he noted, does not refer to one ‘essential’ thing because it is actually an aggregate of many different, complex forces. This warning is one that reverberates across contemporary evolutionary writing, too. In his discussion of the scientific accounts of hominisation, for example, Fuentes emphasises the import of the ‘youngness’ of our species. We are a remarkable animal, he writes, for two reasons in particular: ancestral humans spread out across the planet more than any other mammal, as well as being the genetically most similar species. Another way to put this is that, despite the prevalence of pseudoscientific talk about race, we are all one ‘subspecies’. There is no biology to race. Our species is far too recent, in terms of species development, to have acquired any deeper differences. There’s more genetic diversity within human populations than between them.

And yet this fact, scientifically understood for decades, is still a source of confusion for many. In my own classroom, students will bravely admit to their own presumptions that equate ‘race’ with ‘Nature’, before diving into a wealth of material that helps them correct this equation. This longstanding mistake about evolution and race is one that existential philosophy can illuminate, at least in part.

We all live the strange ambiguity of existence, Beauvoir wrote. We are each objects that can be observed and studied, and we are also subjects, free to become ourselves, spontaneously. Evolutionary science can aid us in reflecting on the first part of this interplay: what it means to be animals, members of our human species. But it’s the latter element that requires additional resources. After all, as Beauvoir put it throughout her writings, it is existentially degrading to ‘freeze’ ourselves as if we are solely bodies or things. To freeze myself or another, as a thing rather than an existing person, is to valorise what exists in the moment. There’s no historical or evolutionary development here. Acting as if there is no past, the existentialists explain, makes the same error as attributing everything to the past.

I am implicated, in the landscape, by the haunting presence of the past in the here-and-now

It’s the feedback loops that seem especially relevant, when it comes to diagnosing our existential choices. Increasingly, philosophers are coming to agreement on how to interpret Beauvoir’s and Sartre’s early writings from the 1940s. While Sartre was the famous philosopher, well-known for his abstract declarations about freedom, it is becoming clearer from biographical and wide-ranging studies of Beauvoir that she is the thinker who put ethical concerns at the centre of existentialism. Already in the 1940s, Beauvoir was describing ‘choices’ in terms of sedimented feedback loops. Meaning-making, or choosing one’s birth, is about navigating the pathway between what’s stable and what’s affectable. It’s only when something given (some aspect of my bodily existence) opens up into something that can be chosen or imagined that existential choice gains meaning.

What seems especially noteworthy here is the dynamic between plasticity and programming. Conrad Waddington, the scientist who coined the word ‘epigenetics’ in the 1940s, described this dynamic as the canalisation of development. This is a way to draw out the temporal movements of the strange ambiguity of becoming human.

I am embodied, with movements and indiscernible habits that accrue over time. I can sustain shocks and disturbances precisely because of developmental grooves, or ontogeny. I am more comfortable over here than over there, through my habits and daily choices. But, as the existentialists wrote, I am also free, capable of responding in new and spontaneous ways. It requires disorientation, sometimes in momentous ways, to disrupt our habits and feedback loops.

My mother grew up in Friesland, the northern province of the Netherlands, and when she was a teenager, she biked past Westerbork every day on her way to school. Today, Westerbork is a name that conjures the horrors of Nazi-run Europe as the transfer camp for Dutch Jews and everyone else who was targeted for extermination camps. Westerbork is where Anne Frank spent her last days in Holland before being transported to Auschwitz and then to Bergen-Belsen where she died in 1945. It is also where Etty Hillesum was incarcerated, together with her parents and brother, and from which she wrote letters to her friends in the months before they were all murdered at Auschwitz in November 1943. The name Westerbork, Etty wrote, ‘will reverberate in our ears for the rest of our lives’, a name for misery so beyond reality that it should be described as grotesque.

Cycling past, my mother saw Westerbork as familiar and unremarkable; she had no sense of the horrific import of the camp. It was decades later, after a 15-year study by the Jewish historian Jacob Presser was published in 1968 and the camp was converted into a memorial in 1983, that the name Westerbork began to resonate again, marked and salient with history. When I listen to my mother’s stories today, I hear a visceral sense of Westerbork being always close by; the keen break in the once-smooth landscape is spatial, but it is also temporal, and the storytelling makes the historical events utterly contemporary in their import and meaning.

In Pyrrhus and Cineas, Beauvoir returned again and again to the existential meaning of this kind of break. I might well relate to the ebb and flow of time, she wrote, as if time did not matter to who I am, or I might hear time as a call in need of a response. This call opens up a disorienting abyss of freedom: I am implicated, in the landscape, by the haunting presence of the past in the here-and-now.

Our bodies are permeable, not only to impacts of past events but also to factors in the environment

Researchers who study epigenetics sometimes refer to ‘ghosts in our genes’ as a way to conjure up the afterlife of experiences, extending the timeline of bodies beyond individuals. Rachel Yehuda, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, noticed commonalities in the children of Holocaust survivors, linked to epigenetic markers that could be empirically tracked. Transgenerational inheritance in humans remains a question among scientists; some point out that uncontested evidence is mostly about plants. Nonetheless, data from researchers such as Yehuda make the biological effects of trauma and genocidal violence available for scientific analysis. For many, such scientific studies hold ethical promise, demonstrating the long arc of injustice from one generation to another.

The 1940s slogan ‘existence precedes essence’ remains vibrantly relevant. Choosing my birth, rather than a seemingly absurdist ideal in philosophy, means engaging with the thresholds of life itself. Thanks to epigenetic researchers, we know that our bodies are permeable, not only to impacts from past events but also to factors in the environment. Just as scientists can track the manifestations of epigenetic processes in development and disease, social scientists can examine the close links between exposure to toxins and epigenetics. As time comes to matter, so too do landscapes, contexts and environments. For some thinkers, this is a paradigm shift in evolutionary science. Upsetting many decades of scientific work, it is not information or DNA but its impressionable structures that are the real locus of biological activity. (Activated on or off by chemicals, attached to DNA and its proteins, genes are now understood to be responsive rather than prescribed by heredity.)

There might be an entirely different way in which this existentialist slogan is relevant. Scrutinising the uptake of epigenetics and the ways in which scientists devise experiments to study epigenetic inheritance, the historian of science Sarah S Richardson and colleagues declare: ‘Don’t blame the mothers!’ Just as I began this essay by turning to my mother, Richardson notes how firmly the gaze remains on mothers – as the source of who we are, and why we are that way.

This is not a paradigm shift at all, Richardson suggests, but reflects continuity in habits of thinking. Epigenetics leads to mother-blaming, but not only because of essentialism, which brackets the many salient contextual factors in order to underscore fervent individualism. The environment or ‘landscape’ that gains attention, she points out, is the uterine environment, where mothers are cast as overly influential, especially for the development and ontogeny of their foetuses. This idea, Richardson concludes in a comment piece for the journal Nature in 2014, risks reinstating the pseudoscience of race: racialised women are more likely to receive surveillance, and the policies emerging from epigenetics disproportionately affect nonwhite communities – and women who are mothers, too.

While I need to choose my own birth, existentially and evolutionarily, my birth is not a solo story. This choice brings me to my own mother’s birth, and far beyond, inviting the question of how far, temporally, we extend. What’s the crucial turning point, developmentally, in the emergence of us as ‘us’? Is it the emergence of art, or language, or bipedalism – or something we have not yet intuited at all?

There are only points of departure, Beauvoir wrote. Each individual is a fresh start. And there is a difference between considering who and what we are from the outside (‘a herd of intelligent animals’) and considering who I am as a human in continuity with evolution, not replaceable by anyone else. Choosing my birth means reckoning with how time comes to matter – as ghosts, haunting the present, but also as the very conditions that let me explore what it means to exist.

This Essay was made possible through the support of a grant to Aeon from the John Templeton Foundation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation. Funders to Aeon Magazine are not involved in editorial decision-making.