Just as the thrum of spectators in a Roman amphitheatre must have once climbed a steady crescendo in anticipation of a beloved gladiator; as the noise in the groundlings pit of Shakespeare’s Globe must have risen in advance of the actors taking their places; or as the hordes who thronged New York’s docks begged sailors unloading the latest instalment of Charles Dickens’s novels for spoilers, so does a certain corner of Twitter come alive on Monday evenings.

Every week, as 8pm Eastern Time approaches, up to 10 million women across the United States are gearing up with their best friends and Twitter followers to partake of a cultural ritual so ingrained that it has three spinoffs, countless international versions, and a seasonal spoof on Saturday Night Live. Settling into couches with their Chardonnay and their iPhones, women across the US perch with bated breath until, finally, the weeklong intermission is over and the first images appear on screen. It is ABC’s reality show The Bachelor for which these women have waited all week – and so have I.

My love of reality TV is a seemingly inexhaustible well, as confounding as it is deep. From the charismatic, canny rednecks of Duck Dynasty to the impeccably clad, feuding doyennes of The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills, from the spoiled but sisterly Kardashians to the bullied line chefs of Hell’s Kitchen, from the creative and put-upon designers of Project Runway to the sad sacks of Hoarders, my appetite for humans going on national television to make fools of themselves has yet to be sated.

Part of it has to do with the reality TV of 21st century politics. With Donald Trump – who is, after all, a reality-TV star – seducing millions of Americans in a bid for the presidency that has all the hallmarks of fiction and yet is horrifically real, there is a way in which our reality has become a reality-TV nightmare, full of ersatz trappings and real terror. But there’s something deeper at stake in my love for this post-modern phenomenon.

I’ve always resisted the phrase ‘guilty pleasure’, because that misses the point. It’s not, after all, guilt that’s at stake, but rather shame. We do no wrong by consuming the storylines starring these would-be celebrities, for haven’t they themselves asked to become part of a ridiculous spectacle for our amusement? But the fact that we commit no moral offence by indulging in these franchises fails to explain the greater mystery, which is the pleasure this experience offers, a pleasure that stymies even as it delights. Over and over, I find myself asking, in the manner of an 18th-century professor of rhetoric and Belles Lettres, how could the suffering of others bring me so much joy?

These shows do indeed traffic in suffering and humiliation. Certainly there is a veneer of plot – the pursuit of a husband, the creation of a garment, the opulent lifestyles of the rich and famous, survival on a desert island. And, no doubt, the accomplishments and loves of the characters bring us joy as spectators. And yet, the most cursory glance at any of these franchises will reveal that these weak plot-lines are a red herring, a ruse planted for no other purpose than to catalyse the humiliation of their principals.

Take The Bachelor. For two hours every week, a group of women compete in increasingly humiliating situations for the attentions of a man they have just met, whom they almost instantly begin to believe is their soul mate (at least, this is the conceit of the no doubt partially scripted show). Every episode has the women go on dates with this suitor, either individually or as a group. In addition to the humiliating set-up of one man dating 25 women, the dates themselves involve demeaning ordeals, such as a not-so-friendly game of soccer, the winners of which receive a paltry few moments alone with the eponymous bachelor. There have been dates involving running away from pigs or, alternatively, chasing down pigs.

It’s precisely because of the public shaming that we indulge again and again in shows with no other real purpose than to humiliate their protagonists

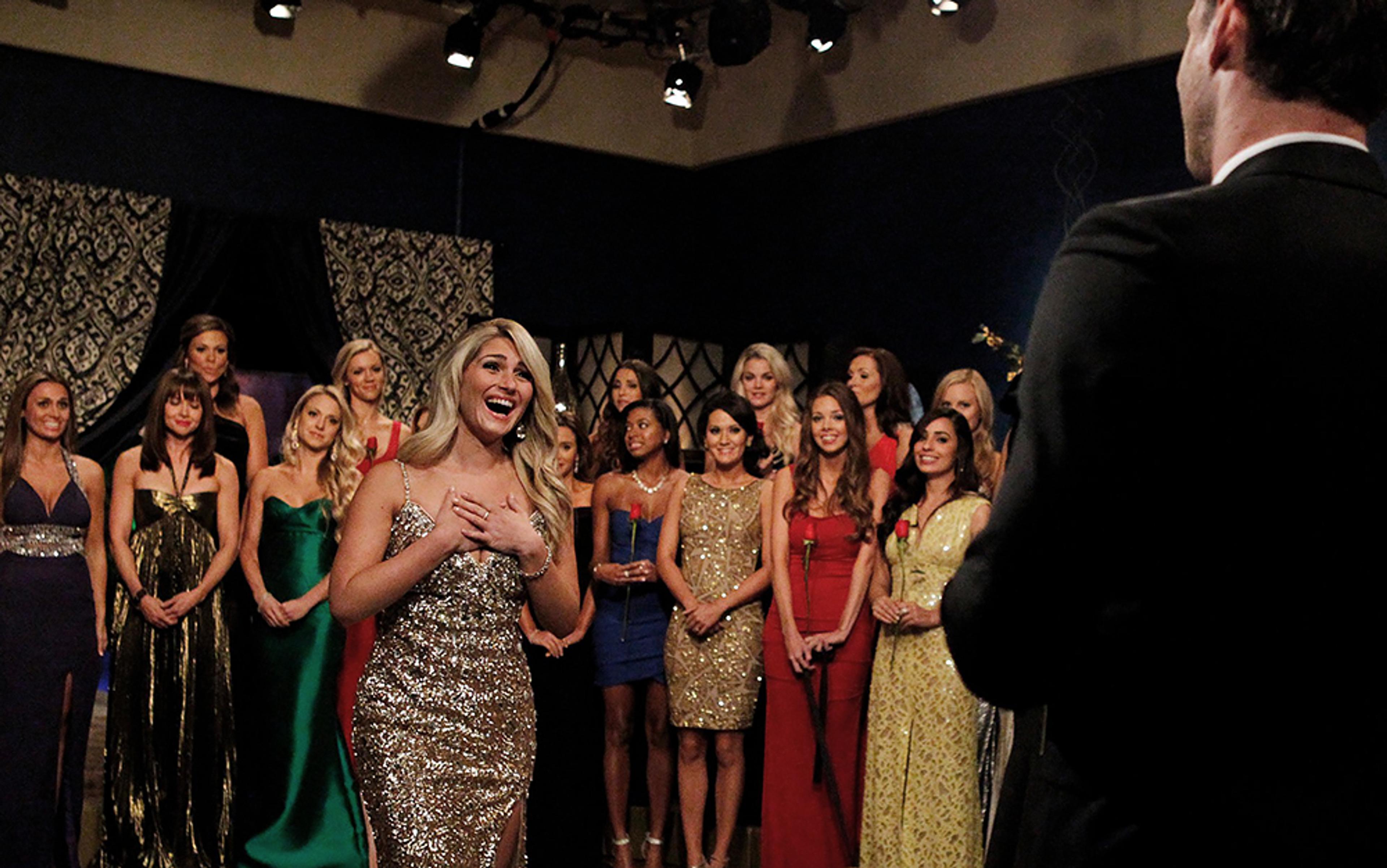

Every episode culminates in a ‘rose ceremony’, a ritual so sadistic that it wouldn’t be out of place in Game of Thrones: the women line up in their cocktail glam, wobbly on four-inch heels and a night of drinking, and wait for the bachelor to call out their names, which he does one by one, in order of their desirability to him. If a woman is lucky enough to hear her name, she is rewarded with a rose and another week in the Bachelor Mansion, where pressure combined with boredom create the ideal conditions for predictably regrettable behaviour. Those whose names are not called are led away to a waiting limousine. With mascara-painted tears streaming down their perfect faces, the spurned young women are interviewed one last time in the limo hurrying them away from the bachelor and back into loveless obscurity. The wheels of the show are greased with the public humiliation of beautiful women, and though I abhor watching people humiliated in real life, somehow, reality TV is not real enough to activate that abhorrence.

The truth is, it’s not simply a lack of abhorrence that I feel towards the humiliations of reality stars. For it is not in spite of these humiliations that we watch – and enjoy – reality TV. It’s not despite the fact that these women are humiliated again and again that we come back every week to find out whom some milquetoast bachelor, indistinguishable from the previous one, will choose. It’s not despite the hoarders’ look of horror as the cameras invade their home, revealing piles and piles of rotting food and 37 broken blenders, that we keep watching.

In fact, by shaming their characters, these shows are trafficking in a very old, very deep aesthetic pleasure. Aristotle called it ‘catharsis’.

Aristotle’s Poetics is the oldest work of literary criticism. In it, the Greek philosopher behind The Physics and Rhetoric outlines the principles at work in great tragedy. Crucially, the plot must be structured so that he who hears the tale will ‘thrill with horror and melt with pity at what takes place’. These emotions – pity and fear – operate like leaven in the audience’s encounter with tragic drama: as the plot unfolds, fear and pity rise and develop within the bosom of the viewer, and a magical transformation takes place. Aristotle called it ‘catharsis’ – which, depending on your interpretation, translates as purification, cleansing or clarification.

What exactly did Aristotle mean by ‘catharsis’? Since the Renaissance, scholars have struggled to uncover the meaning of this elliptical text. Perhaps as a clue, Aristotle insists that only a very specific kind of character can elicit the feelings of fear and pity in us. A virtuous man who goes from good circumstances to bad ones will not do the trick, ‘for this moves neither pity nor fear; it merely shocks us’, Aristotle rather cannily observes. Nor can the hero of a tragedy be a villain whose star is rising, which satisfies neither our moral sensibilities nor calls forth any pity or fear. ‘Nor, again, should the downfall of the utter villain be exhibited,’ Aristotle warns. A plotline involving a villain punished would no doubt satisfy our moral sensibilities, but it would inspire neither pity nor fear precisely because we are so sated on virtue.

Fear and pity, the flint and steel that together ignite cathartic pleasure, require a very specific condition, namely, that the tragedy portray a man like ourselves – neither eminently good nor filled with depravity, but rather, someone whose misfortune is brought about ‘by some error or frailty’. The perfect conduit for catharsis is a character with our own foibles – someone who is otherwise a rather decent sort, but in possession of a fatal flaw that we recognise as our own.

The drama concludes when the character is publicly humiliated for that very flaw, exposing our own shameful desire and its destructive power. We watch with horror as our onstage avatar gives form to our own most shameful wishes, and is subsequently horribly punished and shamed for these desires. The fear we feel of suffering a similar fate expunges – purges – those shameful desires, leaving us with the pleasurable sensation of being conflict-free. Fully repressed, we can return safely to our fantasy of virtue, knowing that, at the very least, no one knows that we, too, are guilty of the very sins for which the character was punished. Man’s goodness is restored, and the world is returned to order. As Jonathan Lear put it in ‘Katharsis’ (1988): ‘There is consolation in realising that one has experienced the worst, there is nothing further to fear, and yet the world remains a rational, meaningful place in which a person can conduct himself with dignity.’

I am able to glean immense pleasure from the humiliation of these vainglorious strivers, these self-important celebutantes, these modern-day Quixotes

My favourite understanding of catharsis is this one. We enjoy tragedy because through it, we are able to purge those aspects of ourselves with which we are most uncomfortable. Our onstage avatar embodies all those thoughts and feelings, desires and fears, ambitions and delusions with which we are most unfortunately cursed. And when fate (or the playwright) punishes her for them, we are purged of those parts of ourselves, at least in the public eye. We become one with the punishers, and the character, Christ-like, suffers for our sins, sacrificed on the altar of our own self-loathing. Thus, we enjoy the suffering, and in particular, the publicness of the suffering. Their shame is our saviour, their humiliation our salvation.

As millions of women – I among them – watch the face of yet another young woman realising that, despite believing herself to be the frontrunner, she has been rejected by her ‘soul mate’, our mouths hang open in dread and delight. There is only one way to describe the immense pleasure I am able to glean from the humiliation of these vainglorious strivers, these self-important overly made-up celebutantes, these modern-day Quixotes convinced that they are the heroes and heroines when all along we know better, we know that the axe was about to fall. There is only one word capacious enough to encapsulate the cringing joy that surges through me as my own deepest, most disavowed fantasies come to light, only to be mercilessly shot down. That word is catharsis.

For we humans are a punitive, self-loathing lot.

Reality TV is no great Greek tragedy. For one thing, it’s not fictional; though no doubt large swathes are secretly scripted, the characters go by their own names, and they are at least supposed to be acting like themselves. But I wish to hazard that reality-TV shows are – like the mini-pizzas you might consume with your squad of besties during a weekly Bachelor viewing party – small, bite-size tragedies. And though the stakes might be low and the plotlines quotidian, the level of catharsis is as deep as it is in the greatest tragedy.

Like mini-pizzas, the catharsis delivered by reality TV is also quite personal. In my own viewing, only certain shows deliver on the tragic function. Some are pure pleasure, like the delightful Duck Dynasty, which might as well be a sitcom for its timing and its cleverness. Some are pure misery, like Gordon Ramsay screaming at those pitiful chefs in Hell’s Kitchen. The Biggest Loser, in which a skinny rich man demands that working-class fat Americans choose between thinness and large sums of money makes me literally sick to my stomach. Others leave me cold, like the rather too polite Great British Bake Off.

In order for that hit of cathartic pleasure to land, the characters must embody a conflict that the viewer, too, struggles with, as Aristotle says. The contestants in the show must be avatars for our own secret flaws. They must possess weaknesses that the viewers secretly share, as well as ambitions and hopes, fears and miseries, with which we are more familiar than we care to admit. In those characters, we see our own secret, shameful attachments portrayed and punished. And through the punishment of our onscreen avatar, we as a society are cleansed of a conflict that modern life has forced upon us, one we have successfully kept secret. Our secret desires remain just so, and as Jonathan Lear says, the world remains a rational, meaningful place in which we can be viewed by our peers with dignity.

For every modern conflict, there is a reality show. Whatever your secret nugget of shame – your inner conflict that even you might not know about – there is a reality-TV programme waiting to grant you the orgasmic relief of catharsis. Do you have a big personality that you sometimes enjoy and sometimes loathe? Jersey Shore will be cathartic bliss for you. Millions of Americans successfully struggle with the desire to let go and eat whatever they want and, for them, those ‘losers’ on The Biggest Loser must be punished for what the contestants self-identify as their lack of control. Many people are conflicted about throwing things away, and shameful piles of junk occupy corners of their homes, making friendly invitations to neighbours an impossibility. For these people, the shame of the hoarder must be purged. Indeed, isn’t the fear of being a loser, and the secret desire of finally being proven the winner, the nugget of pleasure in The Apprentice (and possibly also the pleasure so many Americans are feeling watching Trump make fools of Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz)?

For me – and I would venture, for millions of women watching The Bachelor – there is a central conflict at the heart of being a woman in the 21st century. As the US cultural critic Laura Kipnis put it, many women today are straddling two incompatible desires: feminism and femininity. These two forces are ‘in a big catfight, nowhere more than within each individual female psyche’, Kipnis writes in The Female Thing: Dirt, Envy, Sex, Vulnerability (2006). Furthermore, Kipnis goes on, ‘the femininity adherents aren’t giving up their social rights, while even most diehard feminists aren’t about to surrender the advantages that can be secured through deploying femininity when possible’.

those whose desire is too naked are most viciously targeted by the other contestants, the producers and Twitter for the most abject humiliation

Despite all the gains of the women’s movement, and despite being thrilled that we no longer have to rely on being chosen by a man to thrive, let alone survive, there remains a dark little corner of our Bachelor-lovin’ hearts in which we still want to be chosen by a man – and chosen over other women. Despite our intellectual confidence and pedigrees, and any gains we might have made in this world by the sheer force of our minds, there is a primordial vestige within many of us that wants the competition against other women for a man to be an arena – or really the arena in which we excel. ‘For every bodily advance wrested from nature or society or men, another form of submission magically appears to take its place,’ Kipnis writes. ‘For every inch of progress, a newfangled subjugation. And now, most of them self-inflicted!’ Instead of being forced to bear children, ‘women have chained themselves to the gym’. Instead of foot-binding – ‘Manolo Blahniks, surgery optional to reshape recalcitrant feet for a better fit’. Instead of far less popular The Bachelorette – which someone finally thought to launch, perhaps as an afterthought – it is mostly, regrettably, The Bachelor.

And that is what The Bachelor is purging – modern-day female ambition as it is processed through extremely traditional gender norms; the outsized desire of a 21st-century woman, but relegated to the marriage market, make-up and stilettos, success only at the expense of other women rather than writ large. With its cheeky back-and-forth between infantilising princess-themes and sexy hot-tubs, its erasure of class and race, and its mixing up of love with a competition that no one is allowed to actually compete for, The Bachelor stages the female conflict of the 21st century as a gladiatorial struggle to the death over one man. It is those contestants who are most visibly competing who are most horrendously humiliated in the Bachelor-verse. ‘I just feel like she is the kind of girl who always gets what she wants,’ one contestant on The Bachelor always says just prior to another contestant’s humiliation. Those who want to win, those who strive, rather than passively letting love find them, those whose desire is too naked – these are the women who are most viciously targeted by the other contestants, the producers of the show and Twitter for the most abject humiliation.

Aristotle also had another requirement for great tragedy: the Scene of Suffering, ‘a destructive or painful action, such as death on the stage, bodily agony, wounds, and the like’. Surely no modern-day equivalent exists for this like the final interview of the excised contestant of a reality-TV show, weeping in a limousine ride to nowhere. Or perhaps that’s the sound of my soul emitting a sigh of deepest satisfaction.