Everyone thinks that they know about Casanova, the legendary lover who proceeded from one romantic conquest to another, but almost no one really does. They believe that he was handsome, distinguished and practised in the arts of love, a virtual Zorro of the boudoir. That he was a wealthy member of the upper class, and celebrated in his lifetime for his exploits. So runs the fable of the great lover.

In reality, Giacomo Girolamo Casanova was a far more complex and intriguing figure, a libertine, to be sure, but so much more. And – in case there is any doubt – he was a real person. Born in Venice on 2 April 1725, he was the obscure son of a somewhat famous actress and courtesan named Zanetta Farussi and a forgotten actor, Gaetano Casanova. If anyone in this modest family qualified as a ‘Casanova’, it was his mother Zanetta with her love affairs and wiles and penchant for abandoning him. At the start of 1726, the New Theatre in the Haymarket in London hired his parents along with an ensemble of Italian comedians; Zanetta and Gaetano left Giacomo in the care of his grandmother Marzia. A little more than a year later, Gaetano and Zanetta’s second child, Francesco Giuseppe, was born, and baptised on 1 June. Rumours described him as the bastard child of King George II.

In Venice, meanwhile, young Giacomo suffered from nosebleeds that he said affected his ability to think. His environment was equally problematic. The Republic of Venice, as it was known, was extremely hierarchical, and ruled by 400 families registered in the Libro d’Oro, or Golden book, a directory of Venetian nobility. This rigid structure was destined to collapse under its own weight but, at the time, Venice thrived on sin; it was the Las Vegas of its day. Tourists came from across Europe to sample its gambling dens and its courtesans, and other illicit pleasures. Some convents functioned as harems for the daughters of wealthy families who did not want the girls to marry or to bear children. Under cover of religious vocation, they entertained well-heeled admirers and staged orgies. In time, a ‘nunnery’ became a synonym for a ‘brothel’, as Hamlet said to Ophelia.

As the son of actors, Casanova had no place at all in Venetian society, decadent or otherwise. Actors were outcasts. They couldn’t even be buried in consecrated ground. For Casanova, a career in the clergy was the approved way up and out of the restricted circumstances of his birth. It was a path to education and a secure status in a society. He himself did not feel a sense of religious calling; quite the opposite. He was cynical about the whole experience and wrote about it in amusing, occasionally caustic terms. He did get a sense of excitement when he began preaching sermons, but for Casanova the most important part of the experience was the impression he made on women.

In time, he found a quicker path to women and status as a successful gambler, and left the priesthood, although throughout his life he benefited from the classical education he had received. So he spent the rest of his life manufacturing identities to overcome the disadvantage of low birth. He styled himself as the Chevalier de Seingalt, appropriating a title to which he had no claim. On this basis, he managed to ingratiate himself with the aristocracy, and to gain access to women of the upper echelons, who were, at least in his account, taken in by his impersonation of an aristocrat. Each time he seduced an upper-class woman, he had a sense of evening the score, of striking a blow for the common man.

Casanova claimed that he bedded 124 women – not a lot, perhaps, by the current yardstick of some celebrity memoirs, but more than enough to qualify for libertine status, so long as he did not marry – and he never did. ‘Marriage is the tomb of love,’ he wrote in his memoirs. Who was his greatest love of all the women in his life? A Freudian would answer: his mother, very possibly present in his subconscious because of her absence in his daily life. We know a few tantalising titbits about Zanetta. Ruthlessly ambitious, she abandoned him when he was a child to pursue her vocation as an actress. Casanova saw her infrequently during the rest of his life. She retired on a pension to Prague, at the time a centre of the arts, after a reasonably distinguished and scandalous career performing in commedia dell’arte.

In writing Casanova’s biography, it seemed to me that his guiding passion throughout his life was finding women whose love and attention could fill the void left by Zanetta. He met striking, brilliant, desirable women, never spending much time with them, but often devoting years of thought to them after the fact. Among the most prominent was the well-born woman Casanova called ‘Henriette’. Other affairs, with courtesans, prostitutes and scam artists, were more sordid. Some of his affairs were adolescent and shallow; others exploitative and selfish, and some, especially in England, seemed doomed to fail and painful to hear or read about. A select few were exquisite. At least he was willing to learn from most of them, claiming: ‘I don’t conquer, I submit.’ Or so he said. And at times he did just that. At other times, he was quite calculating and predatory. Yet many women eluded his grasp, and he regretted coupling with others, especially those who imparted sexually transmitted diseases. By his own count, Casanova suffered no less than 11 outbreaks of venereal disease during his lifetime, an affliction that was the bane of a libertine’s existence.

The real-life Casanova bore scant resemblance to the popular image of the fabled seducer. He was tall, at least 6ft 1in (185cm), swarthy, sturdy, with a large forehead and prominent nose that gave him an awkward appearance. He wore a powdered wig, in the fashion of the time; silk breeches; a satin coat; lace trim; a black cloak or tabarro; a three-cornered black hat; and, in true Venetian fashion, a rigid white mask or bauta that the wearer could keep in place while eating and drinking. Only male citizens of the Republic could wear the bauta. Women generally wore the eerie black moretta, a mask held in place with a button between the front teeth, preventing them from talking. Aside from masks, men and women dressed almost identically, as if at a perpetual costume ball. Legend has it that the original invaders of the Venetian lagoon wore masks for protection and disguise, and they continued the practice by law. In Casanova’s day, masks gave Venetians licence to seduce, steal and commit all manner of crimes, including murder.

It might seem that Casanova’s uninhibited existence marked him as a man ahead of his time, but was a man of his time, a libertine

Men found the real Casanova off-putting and pompous. ‘I thought him a blockhead,’ wrote the biographer James Boswell after they met. ‘He is a dandy, full of himself, blown up with vanity like a balloon and fussing about like a watermill,’ said the Venetian playwright Pietro Chiari, a bitter rival. On the other hand, women were attracted by his charm, attentiveness and agile cunning. Although he was reluctant to admit it, Casanova was not completely heterosexual; one of his chief early loves was a young man, or so he believed. He later discovered that the object of his adoration was really a well-disguised woman.

His feelings about women, and experiences with them, were so complicated and varied that it took Casanova 12 lengthy volumes of memoirs to sum them all up. For him, women were the focus of his life. It might seem that his uninhibited existence marked him as a man ahead of his time, but he was not. He was a man of his time, a libertine. He associated with other libertines in Venice, and later in Rome, Paris, Prague and London. Courtesans, prostitutes, gamblers and cardsharps populated his world, and the libertine lifestyle was everywhere – in the French court, where Madame de Pompadour ruled over Louis XV’s large harem; in Rome, where orgies were commonplace (and too wild even for Casanova); and in Venice, where the convents doubled as bordellos.

Nor was the libertine existence confined to the margins of society. Priests and popes participated in the merrymaking, oblivious to the hypocrisy of siring children or keeping young mistresses and catamites. Some libertines wrote about the lifestyle, notably Denis Diderot, the co-founder of the renowned French Encyclopédie (1751), whose sombre erotic novel, La Religieuse (written c1780; published 1796), detailed the illicit affairs of a cloistered nun, but no one did it better than Casanova. For his readers, there is much to learn about love in the pages of his memoirs, its splendours and follies and tragedies. He ennobled women, in general; they weren’t the ‘lesser sex’. But there’s no question that on occasion he exploited them, and vice versa.

Casanova had a large repertoire of seduction techniques – gifts, flattery, persistence, deception, new-fangled birth-control devices such as condoms, and eloquence – and he never lost his sense of excitement whenever the penny dropped. One could always confess one’s sins in church on Sunday. Actual guilt or shame played no part in his daily life. He was a trickster, narcissistic but also generous. He was highly attuned to the amount of pleasure he gave to a woman, or that she experienced with him. Female sensual pleasure and orgasm – la jouissance, as it was called – was of paramount importance. His emphasis on giving the woman sexual pleasure was the secret of his success as a lover. The more pleasure he gave, the more he received.

By means of rope and sheets, Casanova lowered himself to the ground, boarded a waiting gondola, and fled Venice

Casanova’s other great ambition concerned letters. He occasionally published anonymous poems and stories in the Venetian newspapers; there were many to choose from. In today’s culture, he would almost certainly have been a blogger; the anonymity and ubiquity of the internet would have suited him and his risqué inclinations. On one occasion, he carelessly read one of his transgressive poems to an agent of the omnipresent Venetian Inquisition, Giovanni Manuzzi, who reported: ‘He claims its subject will surprise without equal because it deals with intercourse in the direct and indirect way, mixing fables, sacred and profane writings, and the birth of Jesus Christ.’ That was blasphemy, a worse sin in Venice than infidelity or other sexual irregularities. In a subsequent communiqué, the same agent warned: ‘In order to gain fame for his satires, he circulates them among the noblemen, thinking in this way to gain merit in their eyes, and they dismiss him as an impostor and a good for nothing.’ It was time for the agents of the Inquisition to pounce.

On 26 July 1755 at daybreak, 40 armed men burst into his small suite of rooms and arrested Casanova in the name of the Venetian Inquisition. They searched his bookshelves, noting questionable volumes such as the Kabbala and erotica. ‘Those who knew I had those books thought I was a magician, and it rather pleased me.’ They hauled him away once he had dressed in a crisp shirt with ruffles, a lightweight silk cloak, and a stylish cap decorated with lace and a feather. What better way to meet his fate in the drama of his life? He was led across the Bridge of Sighs to the dreaded Piombi (the Leads), beneath the lead roof of the Doge’s Palace. Prisoners in the Piombi never left alive, and no one had ever escaped. Casanova found himself in a state of shock as the Inquisitors formally charged him with possessing forbidden literary works. He was shoved into his cramped cell. Not since his earliest boyhood had he known such deprivation, helplessness, and claustrophobia. ‘I succumbed to something very like madness,’ Casanova recalled, ‘howling, stamping my feet, cursing, and accompanying all this useless noise that my strange situation drove me to make with loud cries.’

During his confinement, he plotted his escape. After months of digging, and with the help of a defrocked priest in the adjoining windowless cell, he managed to flee late on 31 October 1756. By means of rope and sheets, he lowered himself to the ground, boarded a waiting gondola, and fled Venice. Casanova is believed to be the only person ever to have escaped from the Leads. The feat made him briefly famous, and he later wrote – in French – an entertaining and dramatic bestseller about his dramatic exploit, Ma Fuite (‘My Flight’).

After his escape, Casanova arrived in Paris virtually penniless, and eventually talked the powers that be into establishing a lottery that would sustain the École militaire and the French monarchy – that is, until 1789. He became rich from his proceeds, but soon lost his fortune in ill-considered business ventures. And there were unintended consequences. Casanova would inadvertently bring about the fall of the Venetian Republic. One of the first students at the École militaire happened to be a young Corsican named Napoleon Bonaparte. In 1797, Napoleon conquered Venice, bringing about the end of a fiercely independent, millennium-old Republic.

Casanova himself was engaged in a different sort of conquest. He travelled extensively, usually by stagecoach, occasionally on foot. He spent a considerable amount of time in Russia advising but not seducing the young Catherine the Great (still, the thought must have crossed his mind) and in Spain, which he found too severe and pious for his libertine taste, and he was able to make few conquests.

He generally had better luck in Paris, where he began a peculiar relationship with one of the wealthiest women in France, the 63-year-old Marquise d’Urfé, who hosted a salon devoted to exploring the occult. Professing to share the Marquise’s fascination, he flimflammed her into believing that she could become reincarnated as herself. All that was needed was for him to impregnate her with three ejaculations, for which he expected her to pay handsomely. Arranging for a naked dancing girl to set the mood for their ceremonial lovemaking, he claimed to achieve three orgasms, although he simulated two of them. The Marquise d’Urfé failed to give birth to herself or to anyone else, and Casanova, dropping all pretence, abandoned her and in June 1763 fled to England. Although London was nearly as licentious as Paris, Casanova found it difficult to make a name for himself. It was as though he had progressed from Les Liaisons Dangereuses to The Beggar’s Opera.

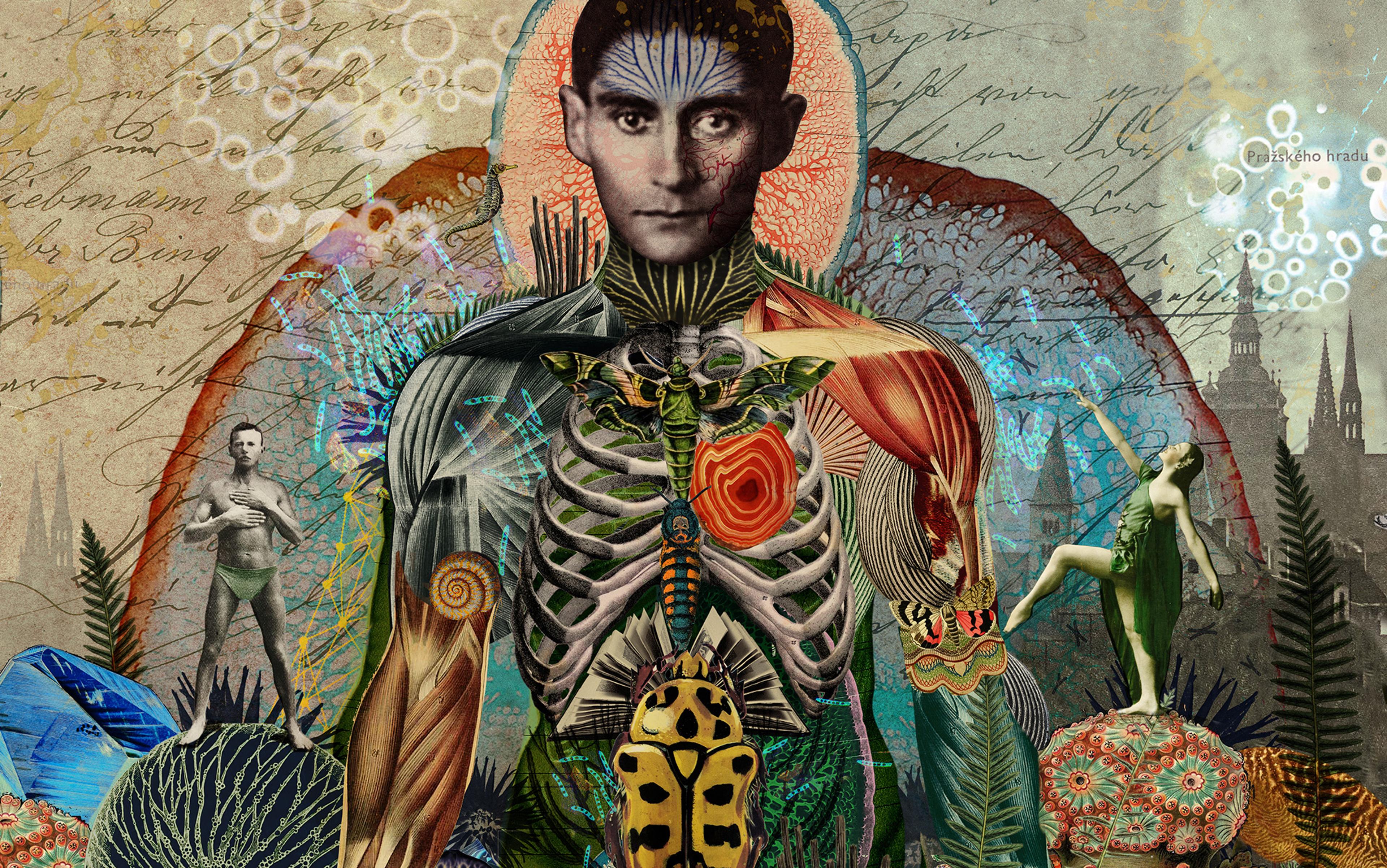

In his later years, Casanova drifted into Prague, where his mother lived in retirement, and where he became the boon companion of another well-known, louche Venetian, Lorenzo da Ponte, Mozart’s librettist. At the time, Mozart and da Ponte were working on a ‘Don Giovanni’ opera – it was a popular genre – and da Ponte regarded Casanova as a real-life example. There is evidence that Casanova contributed some of his impressions and experiences to the libretto and might even have written a bit of it himself.

‘I always willingly acknowledge my own self as the principal cause of every good and of every evil which may befall me’

However, when Casanova attended the premiere in Prague, he was not at all pleased with the ending. Why would Don Giovanni go to hell? (That was the point of Mozart’s operatic masterpiece, for Don Giovanni to be damned to pay for his sins.) But in Casanova’s view, Don Giovanni – and by extension Casanova himself – had done nothing wrong and did not deserve such a terrible fate. Seducing women, giving them a little pleasure and getting some in return was no crime, according to Casanova. The opera remained unchanged, fortunately, and da Ponte later emigrated to the United States, where he started the music department at Columbia University in New York. He hoped Casanova would accompany him. Nothing doing. The lifelong monarchist was opposed to the American Revolution no less than the French Revolution, and so he remained in Europe, living in the past.

By 1783, as Casanova approached his 60th year, his vigour began to diminish. His hair turned grey, and his bravado vied with uncertainty. The shadows of approaching extinction seemed to chase him during his travels; his sense of loneliness was so profound that the sudden appearance of a highwayman intent on robbery came as a relief.

Receiving an appointment as the librarian to Count Josef Karl Emmanuel von Waldstein, Casanova took up residence at the enormous Castle of Dux in Bohemia. He devoted his last years to writing – in French – about his adventures, surveying a lifetime of debauchery and social climbing with equanimity and candour. ‘I always willingly acknowledge my own self as the principal cause of every good and of every evil which may befall me; therefore, I have always found myself capable of being my own pupil, and ready to love my teacher,’ he explained in his memoirs. In writing this exhaustive, exuberant chronicle, he finally found the freedom he had sought throughout his tumultuous life. In revealing all, he achieved a measure of redemption. ‘Worthy or not, my life is my subject, and my subject is my life,’ he remarked.

He had already written numerous other works – plays, poems, translations, polemics, and a five-volume science-fiction novel titled Icosameron (1788), but he put his heart into his intimate memoirs. In his hands, they become not only a record of his personal experience, but also a grand tapestry of the private lives of the 18th century, a complete universe of concrete experiences and transient feeling. It is on these memoirs that his legacy rests, and in time gave rise to his colourful posthumous reputation.

In Casanova’s day, his name meant little to those outside his social circle. To the extent that anyone thought about Giacomo Casanova, it was as a scapegrace, gambler and libertine – one of many gallivanting around the Continent. Decades after his death in 1798, when sections of his memoirs began to be published and translated from French into German and English, the name ‘Casanova’ took on special significance. He gradually acquired legions of devoted readers, and achieved full respectability only recently when in 2010 the Bibliothèque National in Paris acquired his entire handwritten manuscript for almost €10 million, and put portions of it online. At the same time, reference versions of his complete memoirs appeared in print. In his lifetime, Casanova aspired to join the company of Voltaire (who dismissed him as a parvenu) and other renowned writers. Two centuries after his death, his fondest wish is starting to come true.