In 1860, Fukuzawa Yukichi, a young Japanese student still learning English himself, accompanied the first ever Japanese diplomatic mission to the United States as its English interpreter. This American encounter, along with a second trip with a Japanese Embassy to Europe in 1862 and a third trip back to the US in 1867, greatly influenced his thinking about Japan and its future. Although Fukuzawa thought that Westerners’ manners were dreadful, he admired their independence of thought and open discourses. On his trips, he focused not on Western philosophy and science, knowledge he thought he could absorb by reading a book on the subject, but on the more practical side of US and European affairs. Who paid for the expenses at a hospital? How was money deposited in a bank and loaned out? It’s an early indication of how Fukuzawa treated Western ideas. He exhibited a pragmatic curiosity about things and notions from the West. They might work for Japan, or they might not; they could be used or tossed away.

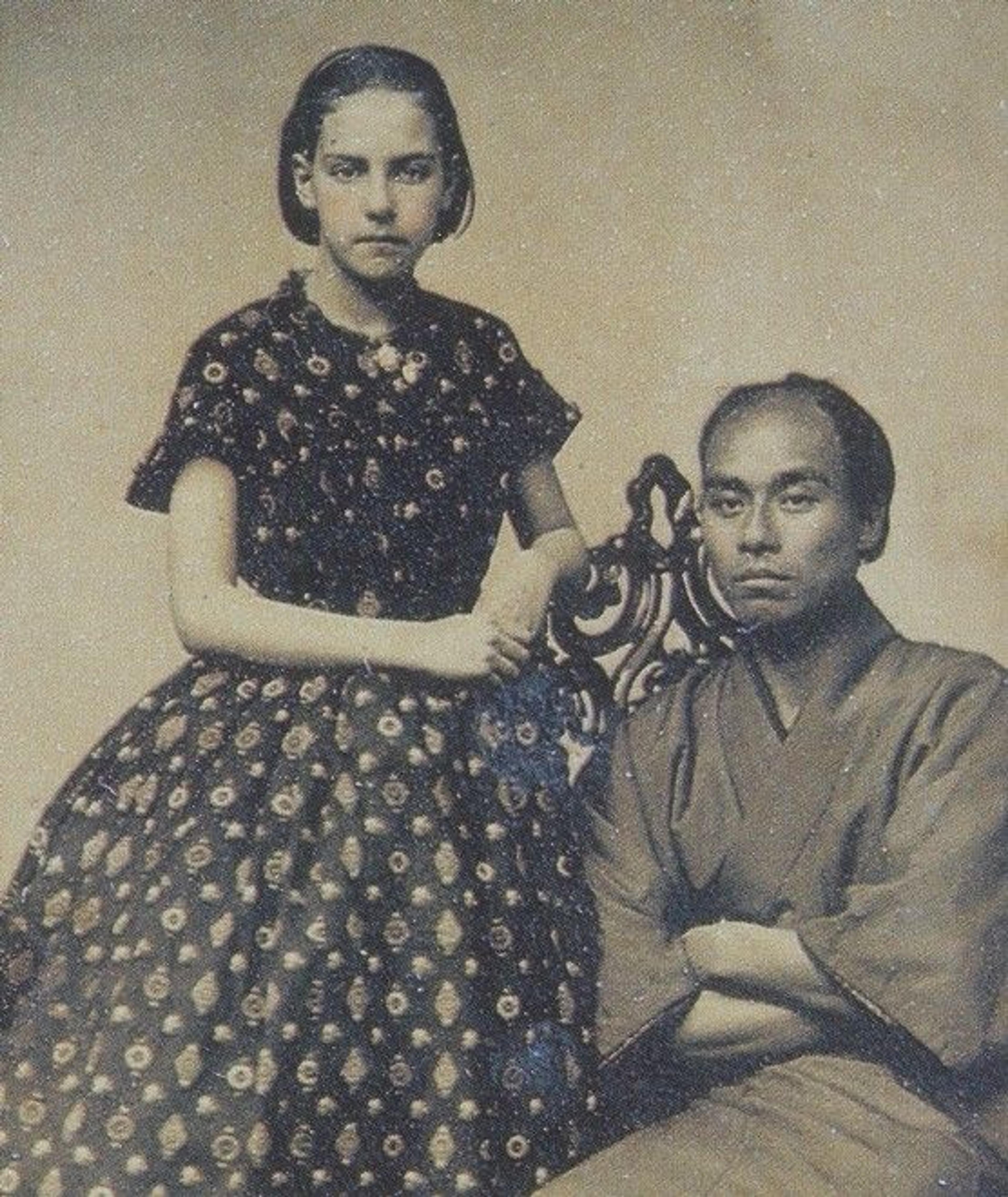

Portrait of Fukuzawa Yukichi by Jacques-Philippe Potteau in April 1862. Courtesy the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford

Fukuzawa’s experiences in the West and his perspective as he eventually became the intellectual founder of modern Japan raise an important question about Westernisation, which was akin to today’s globalisation, but heavily tilted toward Western influence. Did non-Westerners adopt the West’s ways, or did they, like Fukuzawa, question and critique, embrace and reject as they saw fit?

From the viewpoint of Westerners, this was no question at all. The West, especially the US, exerted a defining influence on the world in the 20th century. The immense force of Western institutions – capitalism, democracy, Christianity – stamped itself on other parts of the globe, creating independent democratic nations committed to freedom, end of story. Or is it the end of the story? If 21st-century world trends are any indication, we might have badly overstated Westernisation’s influence and achievement. The success of the non-Western response to COVID-19, especially in East Asia, where countries have remained open while containing the virus, shows the strength of regions outside the West. Along with the appearance of authoritarianism and crony capitalism in some parts of the West, it brings up questions about the dominance and the capability of the region.

An American Carousing (1861) by Utagawa Yoshitori. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The case of Japan, where debates about Westernisation started in the late 19th century, is worth examining for no other reason than it seems to be the perfect example of a country that accepted the Western way of life. One commentator, Henry Field, suggested in the 1890s that Japan’s islands, with their rapid industrialisation and adoption of Western ideas, were like ships being unmoored from Asia, sailed across the Pacific, and attached directly to the western edge of the continent of North America. This geographical metaphor is a bit rich, but it neatly illustrates how deeply myopic Westerners were about Japan’s Westernisation. The problem with this vision is that it was primarily the work of Western intellectuals, journalists, businessmen and policymakers. Henry Luce, a powerful public opinion-shaper as the Time-Life publisher who grew up in China the son of missionaries, encouraged US influence when – in an editorial in Life magazine in February 1941 – he urged Americans to make the 20th century an ‘American Century’.

When one looks beyond Western views, however, we find that almost no Japanese blindly accepted Westernisation. What did the Japanese think about their nation being on the cusp of Western life? They were much less sanguine than Western commentators imagined. Fukuzawa has been widely described as a Westerniser. Even though he resembled a Westerner to some, Fukuzawa’s world, in fact, looked very different from that of the West.

Born into a lower Samurai family in Osaka in 1835, Fukuzawa Yukichi grew up at a time of political disturbances and family disappointment. After a series of crop failures during a famine, a rebellion erupted in 1837, and large parts of Osaka were burned. The uprising failed, but the Tokugawa regime (1602-1868) emerged from the 1830s considerably weakened. Fukuzawa was also profoundly influenced by his father’s experiences in the local clan: he was an accountant but dreamed of becoming a scholar; however, his lord refused to allow him to undertake scholarly studies. Fukuzawa never forgot how the rigid Tokugawa system of rank denied his father. As he later explained in his autobiography: ‘The feudal system is my father’s mortal enemy, which I am honour-bound to destroy.’ Although his father died when Fukuzawa was an infant, the son inherited his father’s commitment to study and improve himself.

After returning to Japan from his trips abroad, Fukuzawa wrote Seiyo Jijo (‘Things Western’), a popular, simple-to-read multivolume compilation of his observations on Western life and institutions. He also wrote two groundbreaking books on learning and civilisation, founded a newspaper Jiji Shimpo (‘Current Events’), a university, Keiō-Gijuku, and even wrote a children’s book on world geography. As a testament to Fukuzawa’s broad influence on Japanese life, today Keio University in Tokyo remains one of Japan’s top schools. Fukuzawa became the most productive and influential intellectual of the modern era. Not only did Japanese elites read his books, but they were also recited out loud to peasants in Japanese villages.

The Japanese needed to mediate the influence of the West carefully

As crucial as his early experience with the West was to Fukuzawa’s thought, he doesn’t deserve the label of Westerniser that many scholars and commentators have given him. While he insisted that the Japanese should learn everything they could about the West, he never endorsed Westernisation. Instead, he scoffed at the idea, arguing that it wasn’t even possible, given the profound differences between Asia and the West:

Even the nations of the West, though they border on one another, are not uniform in manners and customs. Much less can the countries of Asia, so different from the West, imitate Western ways in its entirety. And even if they did imitate the West, that could not be called civilisation.

In other words, the Japanese needed to mediate the influence of the West carefully. Superficial mimicking didn’t equal the spirit of Japanese civilisation and certainly wasn’t a good idea. Fukuzawa’s other point, that there were many Wests, is essential to keep in mind. It significantly complicates the assumed uniformity of the West.

Fukuzawa’s breakthrough work, An Encouragement of Learning, a treatise on education, was published from 1872-76 as 16 different pamphlets. In it, he strongly criticised the old Confucian ways of learning for their uselessness:

In essence, learning does not consist in such impractical pursuits as the study of obscure Chinese Characters, reading ancient texts which are difficult to make out, or enjoying and writing poetry.

These forms of learning were ‘without practical value’ in Fukuzawa’s words. Instead, one should learn so that one can search for ‘the truth of things and make them serve his present purposes’. What did Fukuzawa mean by present purposes? And what ideas had practical value in his view?

Paramount in Fukuzawa’s mind was preserving the sovereignty of Japan:

[T]o protect our country from foreign nations, we must establish a spirit of freedom and independence throughout the entire country.

He argued that the Japanese could create a national spirit of independence only by installing a sense of autonomy among individual Japanese. But this could happen only after the Japanese destroyed the inflexible system of loyalty to one’s lord leftover from the Tokugawa period.

Fukuzawa Yukichi (posing with the photographer William Shew’s twelve-year-old daughter, Theodora Alice Shew), in San Francisco, 1860. Photo courtesy Wikipedia

Fukuzawa’s ideas resonated with political leaders confronting Japan’s extreme challenges in the same period. After the Meiji Restoration – a short civil war that overthrew the Tokugawa regime in 1868 – the new government revamped the political, economic and educational systems, and the military, while reducing Samurai power. They succeeded in all these domestic endeavours, centralising their political control and military power in Tokyo, instituting mandatory education for all Japanese subjects, ending the special status of the Samurai class, and banning the wearing of Samurai swords in public. However, the resulting backlash included several rebellions, of which the most serious, the Satsuma Rebellion (1877), was sensationalised in a US movie, The Last Samurai (2003), featuring Tom Cruise.

Similarly, in foreign policy, the leadership encountered a hostile environment. After Saigō Takamori – the military genius of the Meiji Restoration and the eventual leader of the Satsuma Rebellion – proposed an invasion of Korea in 1873 to sate the restive Samurai, Ōkubo Toshimichi, a fellow leader of the Restoration, argued vociferously against the plan. If the attack failed, Ōkubo pointed out, the Japanese left themselves vulnerable to a Western military incursion that could result in the loss of their sovereignty. He noted that the British held a Japanese debt of £5 million. If the Japanese ran into financial problems and could no longer make payments on the loan, the British had several warships in Hong Kong harbour that would easily outgun Japanese coastal defences. The threat of Western invasion was palpable.

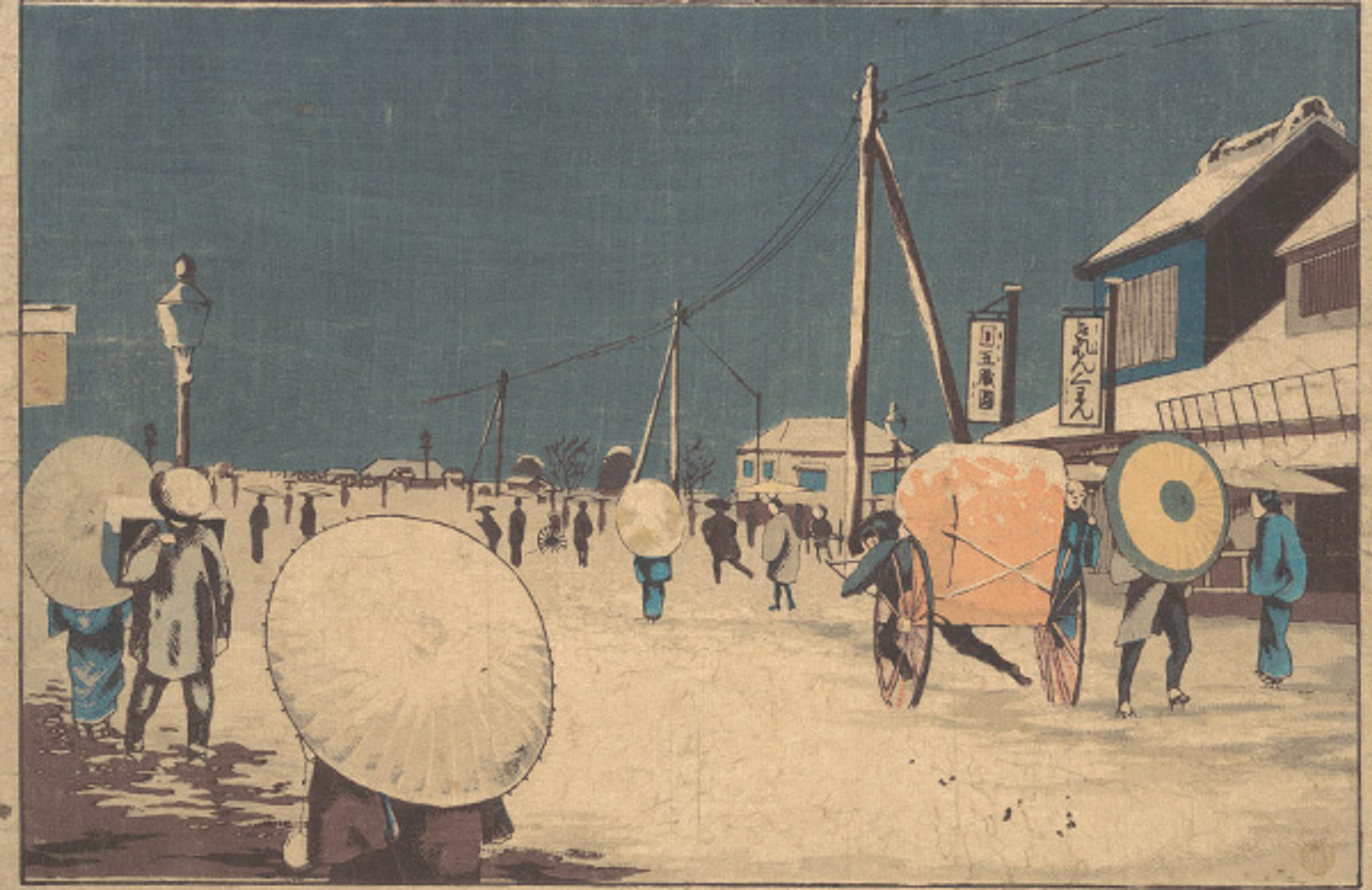

Street Scene in the Outskirts of Edo on an Evening in Winter c1878 by Kobayashi Kiyochika. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fukuzawa addressed the immediate concern about Japan’s independence in a second book, An Outline of a Theory of Civilization (1875). This book, like his first, is considered one of the most important in Japan’s history. It reads as a narrative building to the ultimate goal of a strong, independent Japanese nation. One scholar in 2014 stated that it could have been called An Outline of a Theory of National Strength instead of An Outline of the Theory of Civilization. Fortunately for Japan, its political and intellectual leaders were on the same page; instead of a foreign adventure in Korea, Japan industrialised its textiles manufacturing and built a strong military. As to Fukuzawa’s legacy, far from being a Westerniser, his writings show him to be an independent nationalist. He was mostly concerned not with conversion to Western ways but with building national strength to ward off Western imperialism. It illustrates the chasm between Western thinking about Japan and the Japanese themselves.

Westernisation itself remained the lodestar by which Westerners judged Japan

The influence of Fukuzawa was not limited to Japan. Intellectuals in many parts of Asia read his work and admired his call to build national power. The Japanese nation also became a model for how to cope with the threat of Western power. Intellectuals across Asia, from French Indochina to the Ottoman Empire and many places in between, pointed to Japan’s success as a template for maintaining sovereignty in the face of the Western threat. Rather than imitating the West, they recommended emulating Japan.

If Fukuzawa and others didn’t endorse Westernisation, how did we get the distinct impression that it provided the pathway to modernity for Japan? The answer is simple: Western commentators themselves created the Westernisation paradigm by misinterpreting what they saw in Japan. In his book The White Peril in the Far East (1905), Sidney Lewis Gulick, an American missionary to Japan, clearly argued that the Japanese had already converted to a Westernised system, blithely stating: ‘[W]e count her [Japan] as belonging to the occidental rather than the oriental system of civilisation.’ However, as a progressive, Gulick also critiqued Western notions of superiority and racism toward East Asians in his book.

Americans became less optimistic about Japan’s move to the West in the 1930s as the military took political power, but Westernisation itself remained the lodestar by which Westerners judged Japan. Among these, the political scientist Harold Quigley was sceptical of Japan’s Western credentials, writing the article ‘Feudalism Reappears in Japan’ (1936) in the Christian Science Monitor Magazine. The piece was published immediately after Right-wing military officers from the Imperial Way faction of the Army attempted to overthrow the government and replace the emperor with his brother. The coup failed, the ringleaders were executed, and the Imperial Way faction was purged from the Japanese Army. Quigley saw the coup not as an innovation but as Japan’s return to the past. In fact, just the opposite was true. The coup plotters embraced the new ideas of the Japanese philosopher Kita Ikki, who combined fascism and communism and was executed alongside them. Quigley and many others began to see Japan’s Westernisation as a façade behind which a feudal military stood ready to pull Japan back into history.

Nonetheless, Quigley’s dismissal of Japan’s Westernisation became a commonplace assumption in the Second World War. How else to explain the rise of Japanese militarism out of what Americans had seen as Japan’s thriving Western-style democracy? It had to be from some other time; according to Quigley, the militarists came directly from the Tokugawa period dressed up in the kimono of the Samurai. Some Japanese soldiers did indeed own ceremonial Samurai swords, and the Army trained its troops in Samurai Bushido ideas – they used a pamphlet derived from the Hagakure, a 17th-century text on Samurai ethics. But this internal propaganda was intended to build up their fighting morale, not return them to a past where they would actually use Samurai swords in battle.

The US victory in the Pacific War and its occupation of Japan opened up a tremendous opportunity to Americanise the country, thereby pushing the narrative of Westernisation to its logical conclusion. The US occupiers’ plans included reshaping the Japanese political system, eliminating their military threat, opening up Japanese society to allow for more political participation, decentralising the economic system by getting rid of the Zaibatsu (big companies), regionalising the educational system, and even simplifying the Japanese language.

An ambitious programme by any measure, the reform effort fell far short of its goals. It turns out that converting an entire country to the American way of life was an impossibility, and even incremental change was incredibly tricky. The Americans instituted a new constitution – it might have been their most significant achievement – with the approval of Japan’s National Diet, or bicameral legislature. It remade the emperor into a figurehead, banned offensive military capabilities, and gave women equal rights (something even the US Constitution didn’t do). For a short time, they dismantled the Zaibatsu and supported worker’s rights. But then, confronted with the new reality of the Cold War, the Americans reversed course, reconstituting corporations, arresting union leaders, and shutting down a general strike. The educational system remained under the control of bureaucrats in Tokyo, and language reform was a dismal failure. Thus, to assert that the occupation Americanised Japan is a badly flawed view and a major concession to American hubris.

But this is precisely what the opportunistic professor of Japanese history at Harvard, Edwin O Reischauer, claimed in his books. Reischauer had considerable street knowledge of Japan, having grown up as a missionary kid in Tokyo. He later became so politically adept that in 1961 the John F Kennedy administration appointed him ambassador to Japan, an almost unheard-of plum for a college professor. Immediately following the Second World War, Reischauer wrote two books, Japan: Past and Present (1946) and The United States and Japan (1950); they both became bestsellers, profoundly shaping our ideas about Japan’s Westernisation.

The story of Christianity in Japan reads more like Japanisation than Americanisation

Ironically, Reischauer was a historian of ancient Japan – he wrote his dissertation on the travelogues of the 9th-century Japanese monk Ennin on his journeys to China – and knew little about modern Japan before the Pacific War. But he saw an opening, refashioned himself as a modern Japanologist, and soon became the reigning American expert on Japan. In his books, Reischauer expressed the hope that the US occupation would boost Japan over the finish line of Westernisation. Instead of arguing, like Quigley, that Japan had abandoned Westernisation in the wartime, Reischauer characterised the 1930s-40s as a ‘dark valley’ after which Japan would reemerge into the bright sunshine of American tutelage during the occupation.

Reischauer’s ambitions were immense; not only did he see Americanisation in Japan’s future, but he also saw Westernisation writ large in its past. His writings projected the Westernisation narrative back into the late 19th century and placed the US at its centre; as such, they became some of the most successful pieces of Westernisation propaganda in the 20th century. The fact that the US had negligible influence on Japan in the late 19th century didn’t discourage Reischauer in the least. First, he placed a big bet on our friend Fukuzawa. He argued that the trips Fukuzawa took to the US and his interest in the West amounted to a fait accompli of early American influence. But Reischauer misconstrued Fukuzawa’s interest in the West as a commitment to Westernisation; our examination has demonstrated the wrong-headedness of this argument. Reischauer also misunderstood Fukuzawa’s perspective; what Reischauer saw as progress in Japan’s opening to the West in the 1850s, Fukuzawa perceived as the existential threat of Western imperialism.

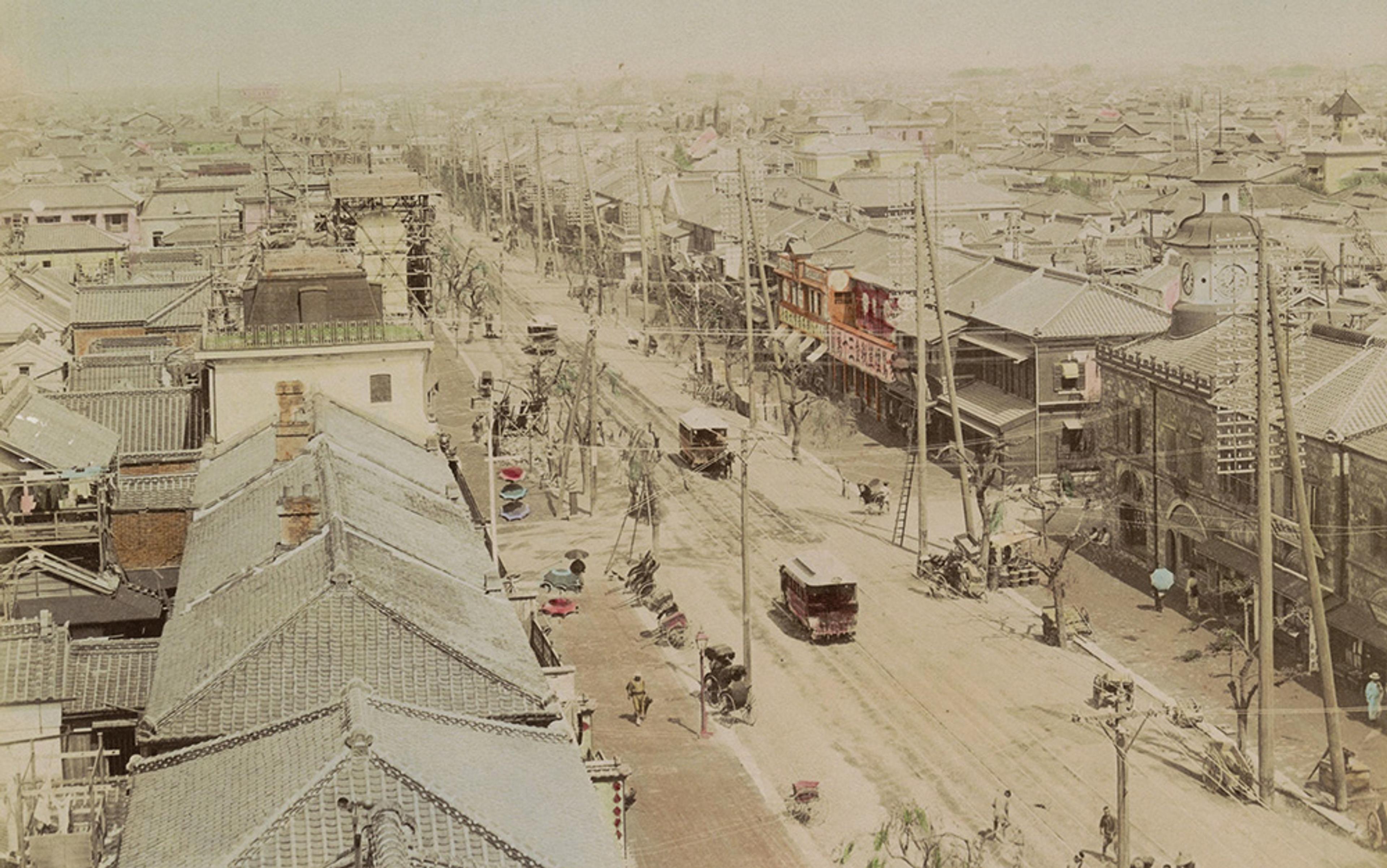

View of Ginza Street, Tokyo c1870-1900. Anonymous. Courtesy the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

So too, with Reischauer’s second example of Americanisation: American missionaries in Japan. He believed that American missionaries shaped Japan’s destiny as a modern Christian nation. In fact, the story of Christianity in Japan reads more like Japanisation than Americanisation. Small numbers of elite Samurai converted to Christianity in the late 19th century, and then they turned the tables on the missionaries and relentlessly pursued a campaign of indigenisation. They took over the YMCA’s governing boards and executive positions, the YWCA, the major churches, and the missionary-run Doshisha University in Kyoto. They also argued that Japanised Christianity, now controlled by Japanese Christians, not by missionaries, should become the central religious pillar of Japanese nationalism. In retrospect, they were less successful in persuading the Japanese to accept Christianity than in kicking out foreign missionaries. Today, Japanese Christians comprise less than 1 per cent of Japan’s population.

Nevertheless, Reischauer took the raw putty of Westernisation and sculpted it into a master narrative of Americanisation. His influence was so powerful, along with his student Albert Craig, who also wrote on Fukuzawa, that even today, Reischauer’s interpretation of Fukuzawa has considerable staying power. It can be found in mainstream textbooks and in Reischauer’s own books, which are still widely read.

Reischauer’s work raises another question that has lurked behind debates about Westernisation. Who gets to judge whether a nation has followed Western ways sufficiently to warrant the label of Westernised: Westerners or non-Westerners? Reischauer’s answer to this question is apparent; in his view, Westernisation was not a choice at all but either national progress into a Western-oriented future or ‘oriental’ decay if non-Westerners refused to join the path of Westernisation.

The Japanese and many other non-Westerners, however, saw their options as not nearly so binary. Western capitalism proffered by businessmen, for instance, offered riches to the winners and promised to accelerate their development, a promise that in the Japanese case worked; but rarely did development on the Western model go so well in other non-Western countries. As attractive as economic growth was, other parts of Westernisation were equally repellent. Foremost among them was a pervasive fear that Western values abetted by Western imperialism would destroy non-Western national cultures, themselves mythic but extremely powerful.

The Japanese responded to this fear with a campaign to protect their own values, beginning in the 1910s-20s with the intellectual Yoshino Sakuzō’s Democracy Movement (Minponshugi). Yoshino’s case illustrates how different groups in Japan, liberal intellectuals and conservative military supporters, clashed over Westernisation. Mislabelled a Westerniser, Yoshino wanted to adapt (not imitate) Western-style democracy to the Japanese monarchy’s requirements, replacing popular sovereignty with the emperor’s benevolent rule. The militarists and their allies who favoured absolute monarchy held him in visceral contempt for his efforts. When he left his post at Tokyo Imperial University for a better-paying position as a newspaper editor at The Asahi Shimbun, their allies at the paper sacked him. His career destroyed, Yoshino’s health declined, and he died scorned and penniless.

US military leaders still naively equate military bases in Japan and elsewhere with Western values

Anti-Westernisation fever increased with the rise of militarism in the 1930s, enforced by strict censorship and repression by the thought police, the Kempeitai. During the Pacific War, academics, now converted to anti-Westernisation, held a Tokyo conference called ‘Overcoming Modernity’ (it could have been called ‘Overcoming Westernisation’ since they conflated the two together) to obliterate Westernisation completely from Japan. Not everyone agreed that Western influence and connections should cut so abruptly, however. A public opinion poll in 1940 showed Japanese businessmen against conflict with the West. Similar results came from the polling of American businessmen. Notwithstanding the attitudes of businessmen, Japan-watchers in the US (former missionaries, Japanologists, journalists) felt betrayed by Japan’s abandonment of Westernisation, itself a misunderstanding of Japan’s selective approach.

The challenge of maintaining one’s own identity in the swirl of rapid changes continues today, especially amid rampant globalisation, which has fostered its own opposition to the globalising of culture. The experience of East Asians in threading the needle of Westernisation, compromising and assimilating where they need to while keeping their cultural core intact, has today allowed them to prosper and move to the head of a transforming global order.

With a clearer understanding of Fukuzawa’s focus and Reischauer’s failures, we can unwind the assumptions behind the idea of Westernisation. Even though it existed on one level – for example, Western money paid for institutions such as hospitals and universities in Japan and elsewhere – it’s an open question of how Western these institutions remained. In some cases, they were indigenised like the missions in Japan. At the level of ideas, we can see that Westernisation was mainly a Western-produced fiction.

However, the fallaciousness of Westernisation has not damaged its popularity, especially among US military leaders who still naively equate military bases in Japan and elsewhere with Western institutions and values. Only with recent scholarship, such as my book The Limits of Westernization (2019), have cracks begun to appear in this narrative. I suspect that the current decline of American preeminence in East Asia, which accelerated under the mismanagement of the Donald Trump administration, will push experts to reexamine the Westernisation creed further. It seems an unsupportable ideology in the face of American weakness in the 21st century, a time that looks like it increasingly belongs to Asia, not to the United States.

From the author: Our attachment to the West and westernisation as the dominant narrative of modernity has a strong linguistic element in the capitalization of words like westernisation, which have no consistent parallel capitalisation in words like easternisation. But like the idea of westernisation itself, capitalisation of these words has undergone much greater scrutiny recently. The finding of the essay that the idea of westernisation is a fiction produced by groups of westerners at times in the service of western domination places a demand upon critical thinkers not to recapitulate western hegemony and replicate mythology by using capitals for all things western.

From Aeon’s editorial director: To capitalise terms like ‘West/west’, ‘Westernise/westernise’ is to reify them, there is no question, and our author’s point is well-taken. Currently our house style is to capitalise ‘West’ (and its derivatives) when it refers to the idea of ‘the West’, as opposed to that which is simply to the geographical west. Equally we refer to ‘the East’ when it is used as a kind of unifying idea, or indeed orientalist trope. Needless to say our capitalisation of West ought to underscore the artificiality of any simple thing called ‘Westernisation’ as much as it is to give it weight and gravitas, however language evolves, as it should, and we continue to debate and discuss such matters and to be open to our authors’ and readers’ views.