In a dark library lit by a single lamp, four men, a young woman and three children crowd around a circular dais. They are staring at a clockwork contraption called an orrery, housed within giant bands of metal that suggest a celestial sphere. Below, tiny planets rotate around the Sun, orbited by pearl moons. Concentric plates allow the planets to move according to their relative speeds. The lecturer in his striking red gown is pointing to Jupiter’s moons, while a younger man in a purple coat and gold striped waistcoat assiduously takes notes. His notetaking implies the event isn’t run-of-the-mill, but something special and worth recording. A small lamp has taken the place of the central sun in the orrery and throws light upon everyone’s faces. We can only see it as a reflection below the elbow of the silhouetted youth in the foreground – a wick burning in a jar of oil. The lamplight adds an eager gleam to the eyes of the inquisitive young children and illuminates the contemplative gaze of the young man on the right. It highlights the edges of the young woman’s frilled bonnet and the cheekbones of the adolescent who leans over the edge of the orrery in front of us. It is his shoulder that we can look over without feeling as if we are intruding. The lamp illuminates all our faces as our minds are enlightened by the science we observe in action.

Today, A Philosopher Giving that Lecture on the Orrery, in which a Lamp is Put in the Place of the Sun (1766) by Joseph Wright of Derby (1734-97) is rightly considered a masterpiece. When it was first exhibited at the annual exhibition of the Society of Artists in Spring Gardens, London, in 1766, reviewers singled it out for particular praise, saying it was ‘exceeding fine’. It attracted more attention than any other work on display, inspiring one reviewer to break out in rhyming couplets: ‘Without a rival let this “Wright” be known,/For this amazing province is his own.’ Wright’s Orrery was a huge statement from a young and ambitious artist. So why, then, was he overlooked when the Royal Academy of Arts was founded by George III just two years later? When Wright had been lauded as a ‘genius’ at that same year’s Society of Artists exhibition? Why was he not a founder member of the new august institution?

The Royal Academy was founded in December 1768 by George III at the behest of a small number of artists and architects. Membership was limited to 40, meaning more than 160 members of the Society of Artists did not make the cut. The Society had formed only eight years earlier, in 1760, as a way for Britain’s leading artists to meet, converse, study and exhibit together in London. It’s hard to imagine but there were no regular public exhibitions of art before this time. Art was shown to discerning patrons in artists’ studios and viewed in private collections in aristocratic homes. The Society changed this and, for a shilling (around £5 today), anyone could scrutinise the finest paintings of the year. At its peak, it had more than 200 members, including the country’s leading landscape painter Richard Wilson, the ‘grand manner’ portraitist Joshua Reynolds and the architect William Chambers, who would later design the Great Room of the Royal Academy. It also included younger artists such as the American painter Benjamin West and the history painter Nathaniel Dance, as well as Wright himself and his friends John Hamilton Mortimer and Ozias Humphry. These young men were finding their feet by exhibiting in this new annual mixed exhibition. Wright was 30 when he was elected a member of the Society in May 1765, the year his first ‘candlelight’ painting, Three Persons Viewing the Gladiator by Candlelight (1765), was exhibited to favourable reviews. While he was known as a portraitist in his home town of Derby, where he lived and worked, it was his ambitious candlelight paintings that significantly raised his profile in the capital.

Three Persons Viewing the Gladiator by Candlelight (1765) by Joseph Wright. Courtesy Derby Museums

Wright’s friends in London were young and opinionated artists, who were members of the Howdalian Society, but his circle in Derby was older and more scientific. John Whitehurst, a horologist and geologist, lived at 22 Iron Gate, a few doors away from Wright at number 28, while Peter Perez Burdett, a cartographer and son of an instrument maker, lived in Full Street. Burdett was so familiar with Wright that he often borrowed money from him (and never seemed to pay him back). Many of Whitehurst’s friends – including the doctor Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles Darwin) and the potter Josiah Wedgwood – were associated with the Lunar Society, a group of industrialists and natural philosophers who met regularly in Birmingham.

The Lunar Society gathered on the Monday closest to the full moon. Their choice of date is often interpreted as travel related, the full moon offering the best light for journeys home after lengthy meetings. But these inquisitive men (and they were all men) chose the name of their society with care. Most were members of the Royal Society, the prestigious scientific organisation founded in London in 1660, and were fascinated by astronomy, engineering and the latest developments in chemistry and physics. The Moon was linked to Earth’s tides, and the race was on to solve the problem of measuring longitude at sea (not least because there was a £20,000 prize on offer for the first person to do this accurately). Meanwhile, the orbits of Jupiter’s moons were already used to measure longitude on land. Wright would allude to his allegiance to the Lunar Society from 1768 onwards by painting a full moon visible through windows and open doors in many of his paintings, including An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768), The Blacksmith’s Shop (1771) and The Alchymist (1771).

An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768) by Joseph Wright. Courtesy Derby Museums

The Alchymist, in Search of the Philosopher’s Stone, Discovers Phosphorus (1771) by Joseph Wright. Courtesy Derby Museums

Wright drew upon the Lunar Society’s investigations for his candlelight paintings of scientific lectures and experiments. The Orrery is the most masterful of these (matched only by An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump). It is a resolutely modern painting, more than 2 metres wide, on a scale that competed with classical history paintings; one that drew upon the current fascination for scientific learning, and predated West’s revolutionary modern history paintings. Although it was rooted in Wright’s portrait practice, the Orrery was much more besides, because it was simultaneously a manifestation of the sublime in nature, of the insignificance of Man when contemplating the Universe.

Lighting his painting from within also showed a deft understanding of art-historical antecedents. Caravaggio’s theatrical compositions often highlighted faces with a shaft of light, leaving other figures in darkness. His international followers were known as the Caravaggisti, and it is the work of the 17th-century Dutch artist Gerard van Honthorst that inspired Wright to use a centralised light source such as a lamp or candle.

The Supper at Emmaus (1601) by Caravaggio. Courtesy the National Gallery, London

The Procuress (1625) by Gerard van Honthorst. Courtesy the Central Museum, Utrecht

Nothing quite like the Orrery had been seen before in England. Wright’s training in London and subsequent practice as a portrait painter in Derby ensured the faces of those clustered around the planetary machine were credible and nuanced, and he used friends and collectors as models. The painting quickly sold to Washington Shirley, 5th Earl Ferrers, for the impressive sum of £210 (£22,000 today). This was up to eight times the amount he received for his portraits, a price that reflected the painting’s ambitious narrative content and large scale.

The cartographer Peter Perez Burdett, in a detail from the Orrery (1766) by Joseph Wright. Courtesy Derby Museums

Wright’s friend Burdett appears in the Orrery, his tricorne hat under his arm as he ardently takes notes. His own interests were, in fact, not astronomical but terrestrial – he won a £100 prize for his accurate survey of Derbyshire.

Lecturer, based on the horologist John Whitehurst, in a detail from the Orrery (1766) by Joseph Wright. Courtesy Derby Museums

The lecturer discussing the planets was possibly based on Whitehurst, who was researching the formation of Earth at the time, while Ferrers, Burdett’s patron and the purchaser of the Orrery, stands on the far right, admiring his protégé’s diligent notetaking.

Washington Shirley, 5th Earl Ferrers, in a detail from the Orrery (1766) by Joseph Wright. Courtesy Derby Museums

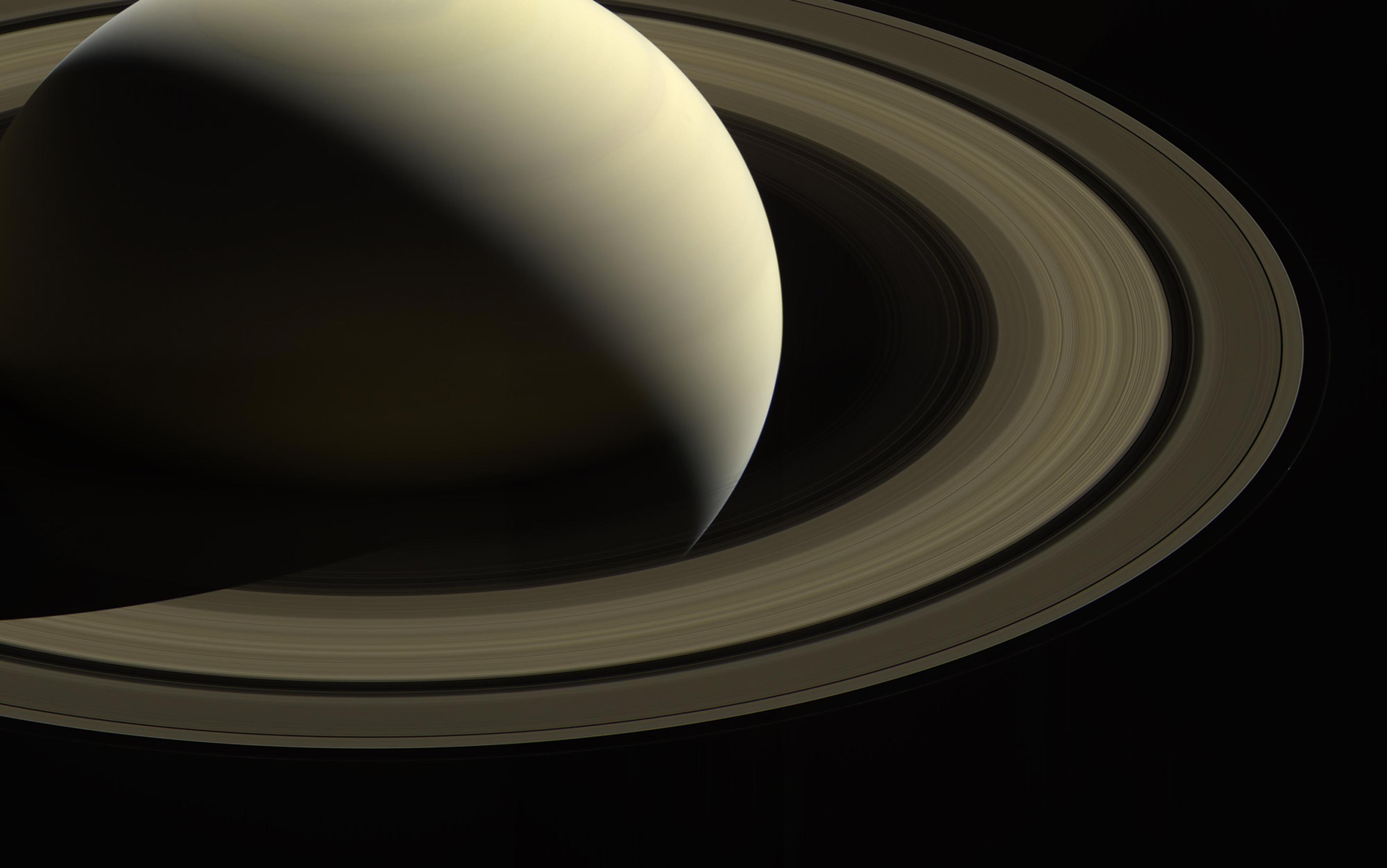

Ferrers may, in fact, have commissioned this painting – his nephew, Lawrence Rowland Ferrers, is the young boy contemplating Saturn. Ferrers owned an orrery, but Wright may have first seen one in action at public lectures given in Derby by James Ferguson (a friend of Whitehurst’s) in 1762. It was designed as an astronomical teaching tool for naval academies, with a brass ball representing the Sun in the centre.

Antique orrery displaying brass planets and orbits on a metal base used to model the solar system. Courtesy British Museum

In some models, the brass ball representing the Sun could be replaced by a lamp to allow the fundamentals of eclipses to be demonstrated. Ferrers, a former naval officer, had been elected to the Royal Society in 1761 following his observations of the transit of Venus, and the ability of Wright’s orrery to show eclipses (of great interest to Ferrers) suggests that Wright chose both the equipment and his sitters with great care.

We can see Wright was well connected in London and Derby, and reviews show that he was well respected, both for his portraiture and his new candlelight paintings. So why was he overlooked by the founders of the Royal Academy? Was it his depiction of science that didn’t chime with their aspirations, or were there other factors at play?

Many of the artists who were founder members of the Royal Academy had formerly been directors of the Society of Artists, including West, Dance and Wilson. They had resigned en masse after a group of young members, including Wright’s friend Mortimer, demanded reform. These young members were sick of the monopoly the old guard held on the director posts, and voted to change the election procedure, wanting those who ran the Society to be the artists who were deemed best on merit, not on seniority or the number of artists they could cajole or even bribe to vote for them.

So, from its very inception, the Royal Academy was a partisan place, founded in retaliation to changes forced through at the Society. Those directors who resigned were appointed to executive posts at the new, rival Academy, and a line in the sand was drawn – to be an Academician, you had to withdraw from all other British art societies. There were grand appointments of overseas artists, including the Swiss painter Angelica Kauffman (one of only two women on the initial roster), and Reynolds was persuaded to become the first president.

Design (1778-80) by Angelica Kauffman. Courtesy the Royal Academy, London

But the founder member places were largely taken up by second-rate painters and jobbing artists – Reynolds’s loyal drapery painter Peter Toms, for example. Samuel Wale, another member, was described by a contemporary as ‘not one of the first artists of the age’. By contrast, none of the agitators for change at the Society of Artists were offered membership, not even Wright. Wright had never stood against the old guard, but his outspoken friends in the Howdalian Society ensured the entire group and its associates were barred from joining the Academy.

If the reason for Wright’s exclusion was largely political, there may have been other factors at play too. The Academy was fashioned on academies on the Continent, in Florence, Milan, Paris and Rome. They followed a classical model, championing ancient history paintings, and religious and mythological scenes over portraits, landscapes and still lifes. The latter were deemed lower down the pecking order when it came to being assigned the best spots in annual exhibitions. There was no provision at all for artists who painted contemporary scenes that aspired to rise above genre painting and domestic conversation pieces. West cannily waited until he became an Academician before he switched from ancient to contemporary historic scenes and, even then, he was seen as a radical. Wright, by comparison, was painting fashionable science lectures that grappled with giant subjects such as our place in the Universe, with life and death from a scientific perspective. There was no pigeonhole for him; no clear place in the hierarchy. His focus on science might well have seemed threatening to traditional religious painting, where only God could play dice.

Wright had made mechanical contraptions as a boy and, in later years, created his own version of the camera obscura to study light and shadow. He painted solar systems and chemical reactions, and experimented with unusual light sources. Two fellow artists who similarly pursued scientific routes were also excluded from the Academy: the equestrian painter George Stubbs and the botanical collagist Mary Delany.

Stubbs had spent 18 months holed up in a barn in Lincolnshire, in the mid-1750s, dissecting an embalmed horse to better understand its anatomical structure. (His painting of the racehorse Whistlejacket is now one of the most iconic works in the National Gallery in London.) Delany painstakingly reproduced the botanical likenesses of nearly a thousand flowers, creating intricate collages that the naturalist Joseph Banks claimed were the only ones he would trust to ‘describe botanically any plant without the least fear of committing an error’. In contrast to the classical idealisation of nature advocated by the Academy, Wright, Stubbs and Delany studied nature for themselves, using the latest scientific discoveries to further their work.

Whistlejacket (c1762) by George Stubbs. Courtesy the National Gallery, London

Passiflora Laurifolia (1777) by Mary Delany. Courtesy the British Museum, London

Wright’s choice of subject matter was not only contemporary, but bordered on the heretical. In his candlelight paintings of the orrery, the air pump and the alchemist at work, he not only employed dramatic lighting and plunging shadows to heighten the drama, but the scenes themselves dealt in mortality and the insignificance of man in relation to the natural world, as well as suggesting that the scientist was now usurping the divine creator.

In the Orrery, a mixed assembly of people, representing the various ages of man, contemplate the solar system from above. Earth is a tiny sphere, barely visible on the right side of the clockwork machine, orbited by one desultory moon. When considered next to the larger spheres of Jupiter and Saturn, with their generous dusting of orbiting bodies, it looks small and insignificant. Man is inconsequential from this perspective, invisible from space. Immanuel Kant, in his Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens (1755) compared the ‘infinite multitude of worlds and systems which fill the extension of the Milky Way’ to ‘the Earth, as a grain of sand, [that] is scarcely perceived’. The Anglo-Irish philosopher Edmund Burke concluded that the starry heaven ‘never fails to excite an idea of grandeur’.

Burke explored the grandeur of the Universe in his treatise A Philosophical Enquiry into our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful (1757) and, long before Caspar David Friedrich and J M W Turner popularised the sublime in art, Wright explored its visual power.

Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (c1817) by Caspar David Friedrich. Courtesy the Hamburg Museum of Art

Snow Storm: Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps (1812) by J M W Turner. Courtesy Tate Gallery, London

The sublime is the sensation we feel when looking at a thundering waterfall or sheer cliff face, or when we contemplate the Universe – a fear, an awe so overwhelming that it affects us in a bodily way. For Burke, not only could natural phenomena on Earth be sublime, but so could the properties of light and dark. He wrote:

Mere light is too common a thing to make a strong impression on the mind, and without a strong impression nothing can be sublime. But such a light as that of the sun, immediately exerted on the eye, as it overpowers the sense, is a very great idea.

Burke’s theory may have informed viewers who contemplated the rotating brass orreries, which taught navigation by day and the sublime contemplation of Man’s insignificance by night. Wright intensifies the viewing experience in his painting, using a small central lamp to transform the library into a sea of shadows, a dark nothingness in which the brass wheels turn and planets rotate. The scale of the painting and the silhouetted figure over whose shoulder we can peer both contribute to the sensation that we are experiencing this phenomenon for ourselves.

In the Orrery, Wright paints a manmade model of the solar system. Increasingly, in his candlelight paintings, he shows the mastery of mankind over nature. In the Air Pump, the lecturer places a live cockatoo – an exotic pet – in a glass sphere, and removes the air to show that nothing can live in a vacuum.

Detail from the Air Pump (1768) by Joseph Wright. Courtesy Derby Museums

Travelling lecturers in fact used something called a ‘lungs-glass’ that replicated this without the need for animal sacrifice. That would be too cruel, ‘too shocking’, acknowledged Ferguson. Wright goes for the dramatic approach, forcing the young girls to hug each other for support as the older one turns away in horror.

Detail from the Air Pump (1768) by Joseph Wright. Courtesy Derby Museums

This isn’t the natural world, but man’s domination of it – nature is imprisoned in the glass and banished beyond the windowpane, where a young boy fiddles with the blind, about to shut out the natural light source of the Moon (full, of course) to maximise the drama. The cockatoo resembles the white dove of the Holy Spirit, and the lecturer, by extension, appears to play God.

Detail from the Air Pump (1768) by Joseph Wright. Courtesy Derby Museums

In 1773, Wright journeyed to Rome, where he stayed for two years. He bathed in its warm, diffused light, and sketched classical ruins akin to those that had formed the setting for The Blacksmith’s Shop.

The Blacksmith’s Shop (1771) by Joseph Wright. Courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery

He never returned to his candlelight scenes, to scientific or industrial subjects, preferring to paint figures in Italianate landscapes and portraits in his studios in Bath and Derby. Wright’s early patron, Ferrers, died in 1778, and the 6th earl (Ferrers’s younger brother) did not care for the Orrery, despite his own son Lawrence Rowland featuring in it.

Lawrence Rowland Ferrers contemplates Saturn, in a detail from the Orrery (1766) by Joseph Wright. Courtesy of Derby Museums

The Orrery was offered for sale at Christie and Ansell, but didn’t attract enough interest to sell, and was bought in by the auction house for £84, a fraction of the original sale price. Subsequent sales saw it changing hands for just £50 before it was bought by public subscription in 1884 for the newly opened Derby Museum and Art Gallery. This was to be a turning point in the fortunes of the Orrery. Today it is greatly admired (alongside the Air Pump), and is Wright’s most celebrated painting. While the paintings of the founder Academicians Toms and Wale have been lost to history, Wright has a suite of galleries dedicated to his work at the Derby Museum and Art Gallery, and is regularly the subject of major exhibitions. So, while the Orrery may not have led to early success at the Royal Academy, it ensured that Wright is now seen as one of the 18th century’s most assured and celebrated British artists.

Photograph of the Orrery (1766) by Joseph Wright on display at the Derby Museum and Art Gallery