I became interested in studying first impressions after my research group discovered that such impressions can predict the outcomes of important political elections. First impressions mattered.

I was in my first few years as an assistant professor at Princeton with a tiny lab consisting of one half-time research assistant and two graduate students. There was no easy way to collect data online at the time, so we participated in one of the ‘questionnaire days’ organised by the department of psychology. These Q days were advertised among students on campus, and those willing to trade an hour of their time for $10 or so were handed a thick bundle of different questionnaires to fill out.

Buried among those were some of our questionnaires presenting pairs of images of the winner and the runner-up from all the United States Senate races for 2000 and 2002, excluding races with highly recognisable politicians such as Hillary Clinton and John Kerry. Different students were assigned to different questions, for example ‘Who looks more competent?’ and ‘Who looks more honest?’ We were hoping that some of these questions would predict who won the elections. When we analysed the data, our hopes were surpassed. Judgments of who appeared more competent predicted about 70 per cent of the elections.

A general rule of science is that results should be replicated, especially if these results are surprising. So we put everything else on hold and started preparing new questionnaires.

We ultimately replicated our initial results and eventually wrote up the findings. The paper was published in Science. This spurred a number of replications by different research groups and in different countries. This was not just a US election phenomenon.

Unexpected findings are typically met with skepticism. Before our findings were published, I applied for funding for this research. The way funding applications work is that you write a research proposal and that proposal is reviewed by anonymous reviewers. The reviews covered the whole range, from the very positive to the very negative. One of the reviewers basically wrote that the kinds of effects we had documented – naive judgments from facial appearance predicting political elections – must occur only in my lab. In their words: ‘Before I would find these proposed studies at all compelling, I would like to see some evidence that this situation occurs anywhere outside of the PI’s laboratory.’ The PI stands for me, the principal investigator. Needless to say, I did not get the funding.

After the findings were published, I received my first hate email. I still don’t understand what instigated it, but its author was pissed off with our ‘trivial’ results. Buried among the profanities, he actually had a plausible alternative explanation of our findings. According to him, it was patently obvious that the observed effects were due to media exposure. Although our participants did not explicitly recognise the faces of the politicians, they must have been exposed to these faces before, and this exposure made them rate more familiar politicians as more competent. If more familiar politicians are more likely to be the winners, this could explain our results. Though plausible, this hypothesis turned out to be false.

The right way to question unexpected findings is to conduct replication studies and test alternative explanations. Political scientists were the first to test trivial explanations, such as differences in the pictures’ image quality or in campaign spending. But such differences could not explain the appearance effects on election outcomes, nor could differences in gender and race. In fact, we obtained our best results when the prediction was limited to elections in which the candidates were matched on race and gender. Familiarity with the candidates’ faces could not explain the effects either.

My favourite replication was a study conducted by John Antonakis and Olaf Dalgas of the University of Lausanne, in which Swiss children’s judgments predicted the outcomes of French parliamentary elections. Some of the kids in the study were not even born when these elections were conducted. In other replications in Europe, judgments of US and Swedish participants predicted the outcomes of Finnish elections. With one of my students and a Bulgarian colleague, we used judgments of Americans to predict the 2011 presidential elections in Bulgaria, the country where I grew up. These elections are interesting because there is a very low threshold for entering the race and, as a result, there are many candidates: 18 in this particular year. It was sad to see one of my professors from Sofia University doing very poorly in terms of both appearance judgments and electoral votes. What makes you a good professor does not necessarily make you a good politician.

In a final twist, Gabriel Lenz and Chappell Lawson, political scientists at Berkeley and MIT respectively, had American and Indian participants rate the faces of Mexican and Brazilian politicians. Although the cultures of the raters and the politicians were deliberately chosen to be very different, the raters agreed in their judgments of the politicians, and these judgments predicted the outcomes of the elections.

But how does this really work in the real world? For one thing, participants in psychology experiments, and certainly kids, are not representative of those who actually vote. For another, it is hard to imagine that political partisans are voting based on the appearance of candidates. What they care about is the political affiliation of these candidates, not their looks.

Lawson and Lenz have done great research to figure out how it might work in the real world. Studying real voters, they found that appearance affects only those who know next to nothing about politics. Being glued to the TV most of the time makes the effect of appearance even stronger. In other words, appearance has its biggest effects on politics-ignorant couch potatoes. Some of them are the swing or undecided voters.

Lenz and Lawson’s findings make perfect sense to psychologists. One of the successful metaphors describing the mind is a ‘cognitive miser’. When we need to make a decision, particularly when we have little knowledge, we rely on shortcuts: hunches, ‘gut’ responses, stereotypes. We use shortcuts because it is easy. We are ready to leap to conclusions, especially when we are too lazy or busy to look for hard evidence. And most of us are cognitively lazy or busy some of the time. When it comes to decisions about strangers, the easiest, most accessible shortcut is our first impression. Unknowledgeable voters go for this shortcut.

Do the effects obtained in contrived lab demonstrations make a difference in the real world? In close races, unknowledgeable or ‘appearance-based’ voters can sway the outcome of the races. Lenz and Lawson estimated that candidates who appear slightly more competent than their opponents can get as much as 5 per cent more votes from unknowledgeable, TV-loving voters. Recently, Lenz and his students conducted experiments with voters in California and 18 other states. In the two weeks before an election day, voters were shown the ballots either with pictures of the candidates or without pictures, and asked to express their intention to vote. Depending on the race – primary or general – when the voters saw the pictures, the best-looking candidates got a boost between 10 per cent and 20 per cent over the appearance-disadvantaged candidates. Lenz estimated that the looks of the candidates could have changed the outcomes of 29 per cent of the races in primary elections and in 14 per cent of the general elections. These results are quite remarkable, because the experimental design rules out the possibility that factors such as candidate effort and spending can explain the effects of appearance. The only difference between the voters in the two experimental conditions was the presence or absence of pictures on the ballot.

One uninteresting explanation of these results is that, once presented with the candidates’ pictures, the voters find their influence irresistible, and this irresistible, immediate influence inflates the effect of appearance on votes. We should be grateful that ballots in the US, unlike in Brazil, Belgium, Greece and Ireland, do not include pictures of the candidates. But, for all we know, the effect of appearance might have been underestimated. Many of the voters in the no-picture ballot condition knew how the candidates look, and this should have minimised the difference between their choices and the choices of voters in the picture-ballot condition. This is testable. Lenz and colleagues reasoned that as the campaign gets closer to election day, the effect of appearance should increase in the control group, which did not have pictures on the ballots. The reason is that voters should be increasingly likely to be exposed to images of the candidates. This is what Lenz and colleagues found. If anything, the effect of appearance seemed to decrease in the experimental group, which had pictures on the ballot, presumably because voters were finding other information about the candidates that influenced their choices. These secondary analyses suggest that the effects of appearance on votes cannot be completely explained by the fact that the voters in the experimental group saw the candidates’ pictures; and that the actual effects can be even larger than the estimated effects. Another depressing finding was that political knowledge did not inoculate voters against appearance in congressional primaries where multiple candidates from the same party were competing against each other.

Appearance-influenced voters are looking for the right information in the wrong place, because it is easy

Occasionally, Abraham Lincoln is described as ‘appearance-disadvantaged’, with the implication that he would not have been a successful politician in modern times. This is a debatable point. Lincoln was the first US presidential candidate to use pictures in an electoral campaign, and he paid attention to the potential effects of his looks. He grew a beard to improve his appearance, possibly on the advice of a group of fellow Republicans who ‘have come to the candid determination that these medals would be much improved in appearance, provided you would cultivate whiskers and wear standing collars’.

One of the most surprising findings in our studies was the specificity of the appearance effect. One particular judgment, competence, was by far the best predictor of the election outcomes. Before our work, there was some research suggesting that more attractive politicians are more likely to be elected. But more competent-looking candidates on average tend to be more attractive too. When you pit these two against each other, perceived competence is a much stronger predictor of electoral success than attractiveness. As it turned out, we were not the first to discover that competence judgments predict elections better than other judgments. When we were describing our findings, we conducted a thorough search of the literature to make sure that we did not miss relevant studies.

In a 1978 paper in the Australian Journal of Psychology, Donald Martin at the University of New England in New South Wales reported that judgments of competence, but not of pleasantness, from faces were a strong predictor of the outcomes of a local Australian election. Our ‘original’ findings were not that original after all.

About 30 years ago, another pioneering study was conducted by Shawn Rosenberg and his colleagues from the University of California, Irvine. After showing that people easily rank photographs of middle-aged men on their suitability for congressional office – ‘the kind of person you would want to represent you in the United States Congress’ – they constructed voting flyers with photographs of ‘highly suitable’ and ‘less suitable’ candidates. Incidentally, attractiveness was not part of the package of Congress suitability: the ‘highly suitable’ were no more attractive than the ‘less suitable’ candidates. Although the flyers presented information about the party affiliation and policy positions of the candidates, the appearance-advantaged candidates garnered about 60 per cent of the votes in the experiment.

But why is perceived competence so important? Voting choices even by unknowledgeable voters are not completely blind. When you ask people about the most important characteristic of their ideal political representative, competence is at the top of the list. How well these perceived characteristics predict elections depends on the importance assigned to them. Voters don’t care one way or another whether their representative is extroverted, and judgments of extroversion do not predict who is going to win the election. But voters do care about whether their representative is competent, and judgments of competence predict the winner. What appearance-influenced voters are doing is substituting a hard decision with an easy one. Finding out whether a politician is truly competent is an effortful and time-demanding task. Deciding whether a politician looks competent is an extremely easy task. Appearance-influenced voters are looking for the right information in the wrong place, because it is easy.

Dominance was bad news for women candidates, whether conservative or liberal

In psychology, we make a distinction between relatively automatic, effortless processes and relatively deliberate, controlled processes. The Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman describes the many ways in which these processes differ in his wonderful book Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011). As he describes it, the system that comprises controlled processes is like an inefficient, busy editor who works with whatever is provided by the system that comprises automatic processes. There are many ways to demonstrate the influence of automatic processes or ‘gut’ responses on decisions. One is to present stimuli for a very brief time; another is to force participants to respond much faster than they would ordinarily respond. In both cases, we make the life of the editor even more hectic.

From the work of Janine Willis, a student at Princeton, we already knew that people could form impressions after extremely brief presentations of faces. A couple of years later, Charles Ballew, another talented undergraduate student, continued this line of work. For his thesis, we revisited our earlier political election studies. We flashed pairs of pictures of the winners and runners-up in gubernatorial elections – the most important elections in the US next to the presidential election – for 100 milliseconds, 250 milliseconds, or an unlimited time until the participant responded. Just as in Willis’s work, a 10th of a second was enough for participants to make competence judgments; and these judgments predicted the election outcomes.

In fact, predictions did not get better with longer presentation of the images. When given unlimited time to look at the images, participants took 3.5 seconds on average to decide which of the two politicians looked more competent. In our second study, we made them respond within a two-second window. Their judgments predicted the outcomes of the elections just as well as when they had unlimited time to respond. There was only one condition in which judgments were particularly poor in predicting the outcomes: asking participants to deliberate and make a good judgment. This might seem surprising at first sight, but there was nothing to deliberate about. These instructions simply added noise to participants’ judgments. We don’t form first impressions by deliberating; they come to us spontaneously.

Occasionally, appearance is explicitly evoked as a reason for a candidate endorsement. As Bob Dole – a runner-up against Bill Clinton in the 1996 presidential election – said of the 2012 Republican presidential nomination: ‘So it looked to me like it would be either [Mitt] Romney or Newt [Gingrich] for the nomination, but … Romney looks like a president.’ Our findings suggest that the influence of appearance might be less explicit and not easily recognised by voters. Character judgments from faces occur remarkably quickly and operate with minimal input from controlled processes. And they matter most under conditions that lead to greater reliance on shortcuts in decisions. In the case of elections, these include lack of knowledge, low stakes, high costs of obtaining information when there are many candidates rather than two, and candidate-centred rather than party-centred elections. All these conditions increase the effect of appearance on voters’ choices.

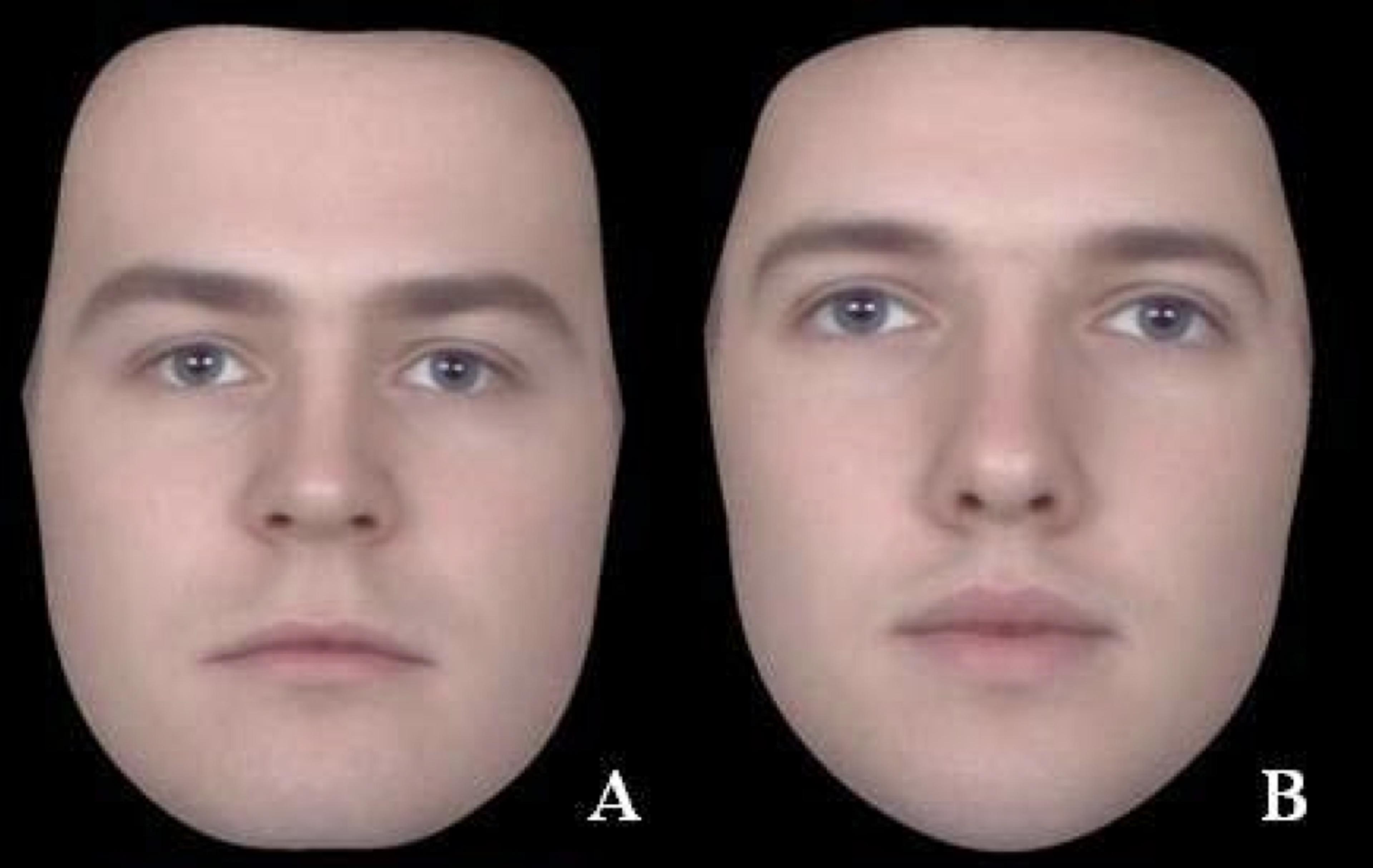

Competence is perceived as the most important characteristic of a good politician. But what people perceive as an important characteristic can change in different situations. Imagine that it is wartime, and you must cast your presidential vote today. Would you vote for face A or face B in Figure 1 below? Most people quickly go with A. What if it is peacetime? Most people now go with B. This preference reversal is so easy to obtain that I often use it in class demonstrations.

Fig 1. Who do you trust in wartime? In peacetime? Courtesy Anthony Little.

These images were created by the psychologist Anthony Little at the University of Bath and his colleagues in the UK. Face A is perceived as more dominant, more masculine, and a stronger leader – attributes that matter in wartime. Face B is perceived as more intelligent, forgiving, and likeable – attributes that matter more in peacetime. Now look at the images in Figure 2 below.

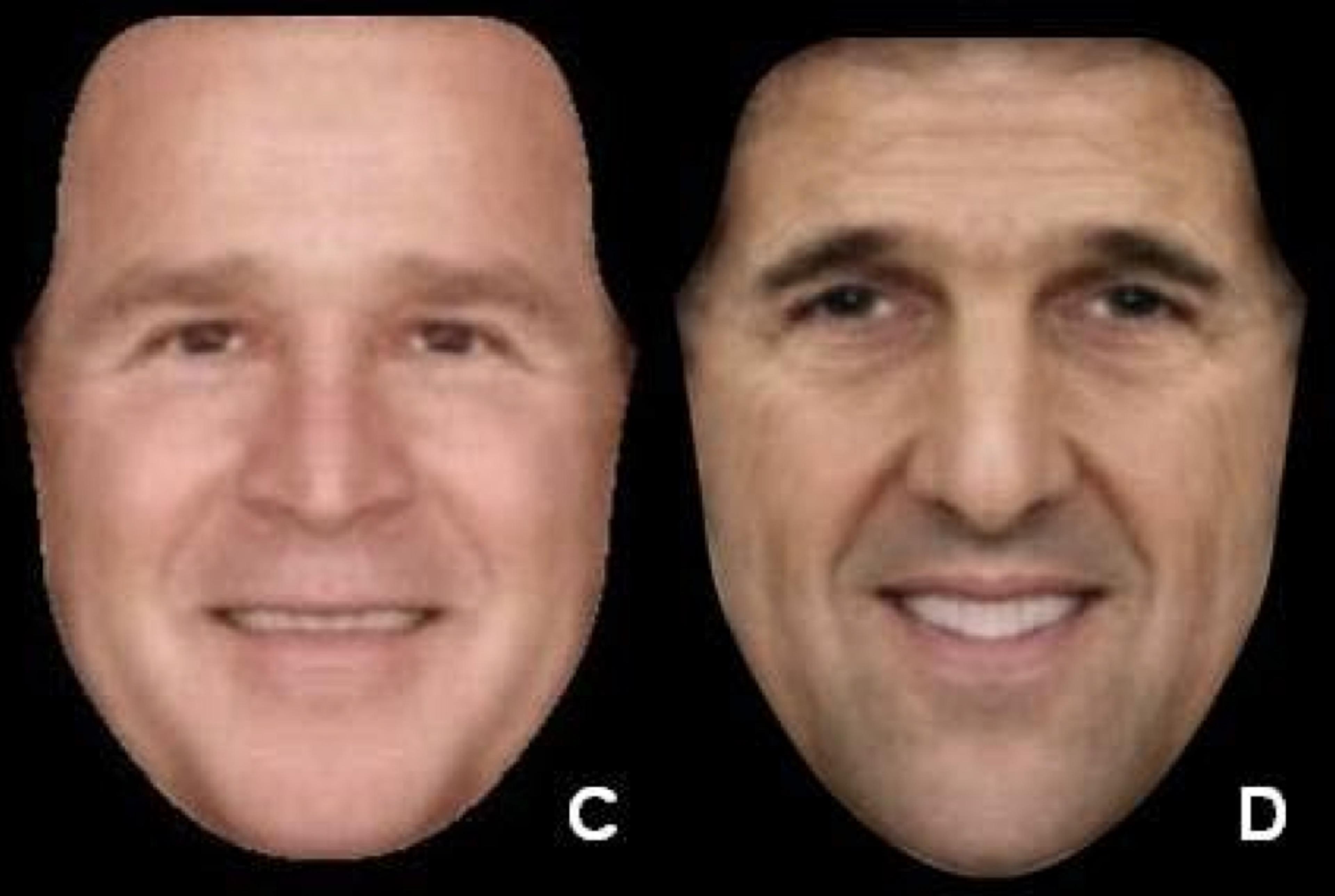

Fig 2. President George W. Bush and Secretary of State John Kerry.

You should be able to recognise the former president George W Bush and the former secretary of state John Kerry. Back when the study was done, Kerry was the Democratic candidate running against Bush for the US presidency. Can you see some similarities between images A (Figure 1) and C (Figure 2), and between images B (Figure 1) and D (Figure 2)? The teaser is that the images in Figure 1 show what makes the faces of Bush and Kerry distinctive. To obtain the distinctiveness of a face, you need only find out what makes it different from an average face – in this case, a morph of about 30 male faces. The faces in Figure 1 were created by accentuating the differences between the shapes of Bush’s and Kerry’s faces and the average face shape. At the time of the election in 2004, the US was at war with Iraq. I will leave the rest to your imagination.

What we consider an important characteristic also depends on our ideological inclinations. Take a look at Figure 3 below. Who would make a better leader?

Fig 3. Visualizing impressions of dominance. Based on the work of Oosterhof & Todorov (2008).

Two Danish researchers, Lasse Laustsen and Michael Petersen, used faces generated by the computer model of impressions of dominance that I and my colleague Nikolaas Oosterhof developed in 2008. Laustsen and Petersen showed that, whereas liberal voters tend to choose the face on the left, conservative voters tend to choose the face on the right. These preferences reflect our ideological stereotypes of Right-wing, masculine, dominant-looking leaders, and Left-wing, feminine, non-dominant-looking leaders. Turning to real elections in Denmark, Laustsen and Petersen replicated the competence effect: an appearance of competence benefited political candidates across the ideological spectrum. But the benefit of dominant appearance depended on the ideological orientation of the candidates. While dominant-looking conservative candidates gained in votes, dominant-looking liberal candidates lost in votes, but only when they were men. Dominance was bad news for women candidates, whether conservative or liberal. Gender stereotypes are hard to beat.

Fig. 4 A Danish politician (original image in the middle) whose face is manipulated to look less (image on the left) or more dominant (image on the right). Courtesy Lasse Lautsen

Laustsen and Petersen also manipulated the faces of actual politicians to look less or more dominant (Figure 4, above). When the politicians were not well-known, this manipulation made a difference. Liberal participants were more receptive to the policy position of the candidate when he was made to look less dominant. In contrast, conservative participants were more receptive when he was made to look more dominant. The situation or our ideological inclinations can change what we consider important, but they don’t change our propensity to form impressions and act on these impressions.

On such impressions elections might turn.

Excerpted from ‘Face Value: The Irresistible Influence of First Impressions’ by Alexander Todorov. Copyright © 2017 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.