‘There is not an animal that lives on the earth, nor a being that flies on its wings, but they form communities like you.’ So states the Quran in ‘The Cattle’, one of many chapters where God praises and even personifies nonhumans. No purer nor worthier than people, animals are also no less precious. Hence why the scholar Sarra Tlili argues that the Quran is theocentric and not anthropocentric; it makes God the core of existence, and not humans, since, as Tlili writes in Animals in the Qu’ran (2012): ‘Any being that worships and obeys God obtains God’s pleasure and is rewarded in the hereafter.’

Here is one of Islam’s first animal texts, but by far not the only one. Pre-Islamic poetry shows desert raiders fast as wolves, or sleek camels with a lover’s grace gone by (‘It were to be wished,’ says the 18th-century linguist Sir William Jones, ‘that he had said more of his mistress, and less of his camel’). Thinkers such as Avicenna credit beasts with humanish insight, like how a sheep senses the danger from a wolf. Islamic legal scholars such as Ibn Abd al-Salam debate human versus animal rights. Legends of Sufi mystics show them strolling with lions and chattering with birds. In the philosophical 12th-century parable by Ibn Tufayl called Hayy ibn Yaqzan – Latinised as Philosophus Autodidactus, and which perhaps inspired Daniel Defoe’s novel Robinson Crusoe (1719) – a boy trapped on an island is saved by a gazelle and becomes a vegan to spare his animal friends.

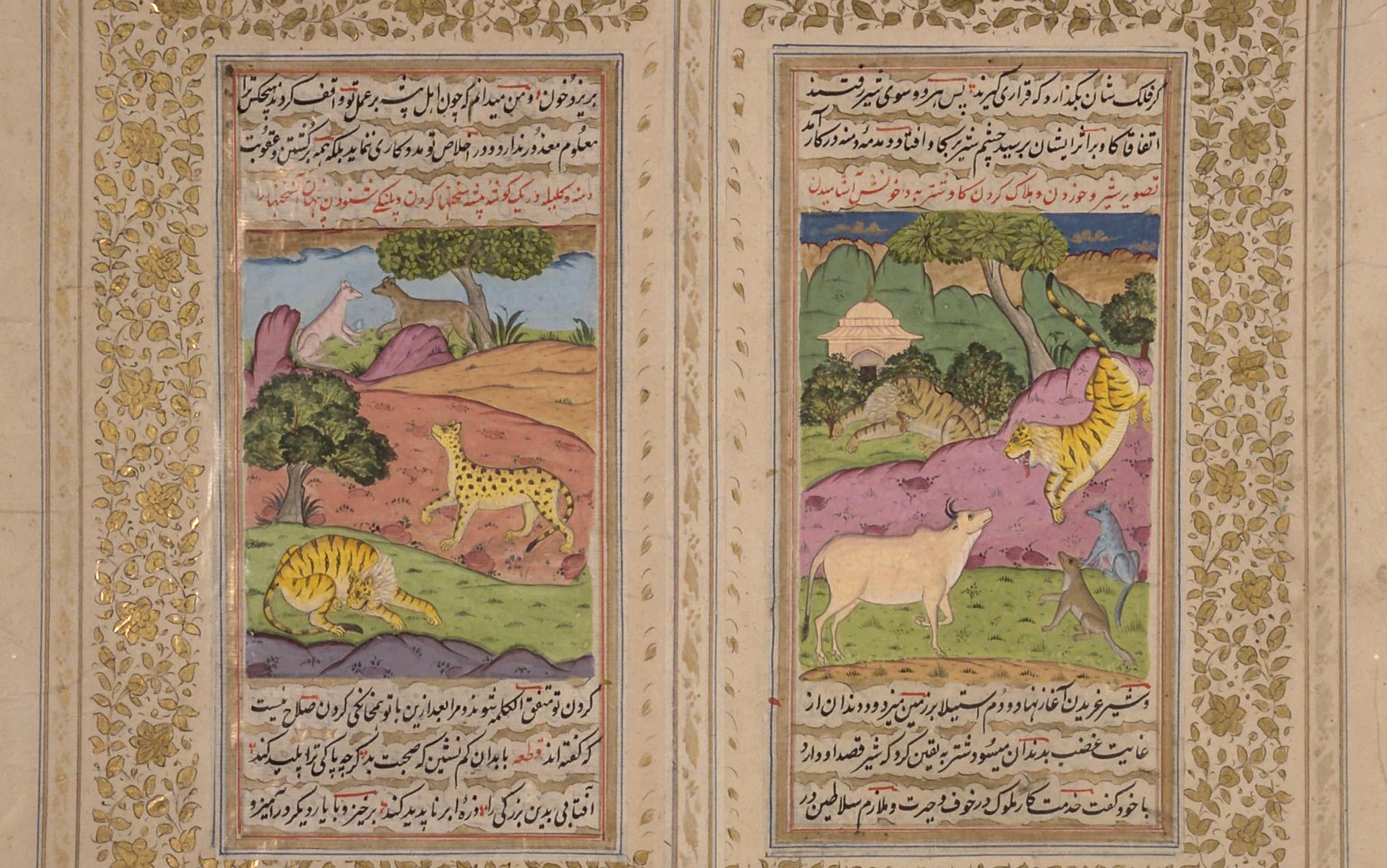

Some of the best-travelled works are moral fables from an Indian guidebook for rulers, a nitisastra, called the Panchatantra or ‘Five Treatises’, dating to c300 BCE. What remains of them, likely joined to parts of the Mahabharata, goes by the title Kalila and Dimna, after the names of two jackals who serve a brave but thoughtless lion king. The stories were translated into Arabic from Pahlavi (Middle Persian) by Abdallah ibn al-Muqaffa’, an 8th-century Zoroastrian convert to Islam. They have witty animal characters who stand for ministers advising kings, friends cautioning friends or wives scolding husbands, all to inspire virtue and judgment in rulers. No wonder readers first took Kalila and Dimna to be a ‘mirror for princes’. As a field guide to wielding power, its tracts suddenly and forever steeped Arab regimes in the brew of Persian courtly culture, thus sealing a legacy for Ibn al-Muqaffa’.

Readers can enjoy these Sanskrit Aesop’s Fables in a new translation by Michael Fishbein and James Montgomery from the Library of Arabic Literature. Kalila and Dimna has for centuries gathered bits of context and personal interest unto itself like briars on a pair of jeans, growing from a single book into a whole written tradition. ‘The statement has been made,’ wrote the Sanskrit scholar Franklin Edgerton in 1924, ‘that no book except the Bible has enjoyed such an extensive circulation.’ To call it world literature barely does it justice.

Long ago in India, the young King Dabshalim was in trouble. He had no experience and was prone to lash out at his subjects, angering them and grinding down their support. One day while in despair, he spied an old scroll with 13 guidelines for leadership. At first, he felt only dejection: the rules were buried in riddle-like beast fables, and unlucky Dabshalim had no way to decode them. But the scroll also named a sage, Baydaba (often written Bidpai), as the right man to explain the tales. Dabshalim sent for him at once.

The brash young ruler soon mourned his choice. ‘Forbearance is the best quality of a ruler,’ Baydaba told him, hinting that Dabshalim lacked this quality. The insinuation outraged the king and landed the old teacher in jail. But, after licking his wounds, Dabshalim took fresh curiosity and released Baydaba, ready to hear and understand the lessons he drew from the stories.

This is the frame story of Kalila and Dimna. Its tone and themes set up the rest of the work. Dabshalim’s rashness, and the animal stories meant to tame it, echo Alexander Hamilton’s opening question in The Federalist Papers (1788), namely, ‘whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.’ This formula favours the wisdom of age over the vigour of youth but, in case one gets stuck with the latter, the trick for any advisor is to instruct the ruler and still keep one’s head.

Getting too close to rulers is like climbing a mountain full of tasty fruit, yet swarming with predators

Kalila and Dimna does this with a timeworn strategy: to delight as much as instruct. ‘One device was to put eloquent and elegant language in the mouths of animals and birds,’ explains Ibn al-Muqaffa’ in Fishbein and Montgomery’s English translation. Such a device lets the stories imply, instead of tell outright. Missing are the wonders of holy men rambling around in Sufi lore. The language is honest and plain next to Avicenna’s philosophic jargon or the verbal feats of al-Jahiz and al-Tawhidi, two medieval stylists who also wrote about animals. Still, the tales from Kalila and Dimna count as literature. Anyone who memorises them in days of youth will unlock their treasures with age, explains Ibn al-Muqaffa’, like parents who leave an unexpected trust fund, ‘freeing their child from the need to toil’.

From here the tale opens in earnest. ‘Tell me a parable,’ King Dabshalim says to Baydaba – in the surviving text, Dabshalim is no tyrant but rather suggests the topics himself – ‘about two friends driven apart by a treacherous liar who incited them to enmity and hatred.’ The old sage warmly obliges him. One day, an ox gets stuck in the mud and brays in anger, startling a nearby lion king. The king asks his retinue for counsel, since it’s unclear if he can overpower the source of this awful sound. The king’s two guard jackals, the titular Kalila and Dimna, argue whether to get involved.

Kalila vetoes the idea. Getting too close to rulers, he says, is like climbing a mountain full of tasty fruit but which is swarming with predators; ‘the ascent may be difficult, but staying there is harder yet.’ Here is another key theme of Kalila and Dimna, namely, the bitter conflicts that so often gush through the halls of power. No doubt Ibn al-Muqaffa’ brought his own struggles to bear. Having ducked persecution as secretary to the Umayyad governors of Shapur and Kirman, and even after the Abbasids overthrew those governors, he finally met the chopping block at age 36 for supporting a rival faction. To him and others who worked on Kalila and Dimna, such intrigues, murders and machinations were all too real.

But for the cunning, ambitious Dimna, meddling in kingly affairs is one temptation too many. ‘Without risk there is no reward,’ he says. Dimna flatters the lion, joins his inner circle, and convinces him to hate the ox without cause, triggering a scuffle that kills the ox and upsets the lion. For committing fraud and pointless carnage, Dimna is tried and executed. ‘Better someone who turns away from his sin, admits it, and confesses,’ declares the judge over Dimna’s not-guilty plea, ‘than someone who persists in his sin or denies it.’

Other fables flow from this fountainhead, letting characters make more than one ethical argument or wise saying at once. In a story about a crow who befriends a rat, the rat describes how he used to sneak food from a holy man, whose neighbour tells him: ‘There must be a reason for this.’ To make the point, the neighbour then unspools his own yarn: once there was a husband who wanted to throw a dinner party but his wife balked since their stores were low. Warning against excessive thrift, the husband reminded her of the greedy wolf who stashed away the body of a hunter, only to step on the hunter’s bow, snapping the string and mortally slashing the wolf’s throat. ‘People who hoard often suffer the same unsavoury fate,’ concluded the husband.

We’re two stories in, and already have several moral maxims. Such nested ‘Russian doll’ narratives can trigger real vertigo, unrolling story after story sometimes in the same paragraph, with uncanny echoes of The 1,001 Nights even though not twirling along for so long or getting so snarled up that readers bumble and drop the thread. Keeping track is all part of the fun.

The wife, chastened by the idea that scrimping has its drawbacks, agrees to the dinner party and starts husking seeds. But then her dog walks by and soils them. She takes the ruined kernels to market and swaps them for cheaper unhusked ones, as some wonder: ‘There must be a reason why this woman traded husked for unhusked sesame!’ – a vivid if abrupt way to show that all things have their cause. Often the secondary stories of Kalila and Dimna halt on such a punch, hanging proudly in the air but with the smell of anticlimax. The point is not to arrive at resolution but at a maxim – ‘There must be a reason for this,’ ‘People who hoard often suffer the same unsavoury fate,’ and so on – that lets the main story roll forward.

Realising from his neighbour’s sermon that everything has its cause, the first man – the one beset by rats – renews his quest to know why. He digs up the rodents’ burrow and finds a heap of money. This, he reasons, must have inspired the rat to purloin his food, or as the rat itself declares: ‘Only money can guarantee intelligence and strength.’ But when the rat comes to steal once more, the man’s neighbour trounces it on the head, helpfully persuading it of a different view: ‘People’s troubles in this world, I saw, stem from inordinate desire incited by greed!’

The rat story shows why it’s good to forsake principle, especially since it saves the rat’s life

Here’s another curious ending. When faced with hunger, the rat puts its faith in money but, when destruction comes, it drops that faith like bits of rotten food. The switch shows why Kalila and Dimna can be ethically murky. Virtue plays second fiddle to pragmatism, or at least it seems so. It doesn’t help that there is much swaying and tottering content, where characters sit on opposite sides of a problem and debate, like Kalila and Dimna agonising over the king, or the husband and wife arguing charity versus thrift. The resulting lessons fall short of the high-minded.

The lion-ox episode, for instance, teaches that friendships sour quickly from scheming rivalry. The rat story shows why it’s good to forsake principle, especially since it saves the rat’s life. In a story called ‘The Turtle and the Monkey’, the turtle must choose between his friend, the monkey, and his ailing wife, who’s tricked her husband into thinking that the only cure for her disease is a monkey’s heart. In the end, the turtle admits its plan to kill the monkey and take its vital organ. ‘I would have brought my heart along if you’d mentioned this to me,’ says the monkey, claiming to have left it at home. Cheered by the news, the turtle lets the monkey go home, where it hides until the turtle calls to it. I know you, says the monkey. ‘You tricked me with deceit and cunning, and now I’ve paid you back in kind.’

With such pragmatism, some have asked whether Kalila and Dimna prefigures the stern, cold-blooded realpolitik of Niccolò Machiavelli. But the question is misguided. Apart from exaggerating the cruelty of Machiavelli’s 16th-century political treatise The Prince, it forgets that Kalila and Dimna does side with virtue, as Fishbein and Montgomery say in their introduction. Qualities such as loyalty, fairness and trust bring good fortune, while errors of reckless judgment turn to rot. Hence the need for rulers to pick trusted friends and advisors, another main theme. Even after the monkey tricks the turtle and runs home, the turtle admits its mistake. ‘This pain has been brought upon me by my own soul, and I have lost a friend because of my own evil inclination.’ Hence the theme that prompted the story: ‘A parable about someone who works hard to acquire a thing, but having acquired it, doesn’t know how to hold on to it.’

It didn’t take long for Kalila and Dimna to sprout wings and fly. This is clear from the giant AnonymClassic database at Freie Universität Berlin, which tracks the book’s peregrinations better than any effort so far. The Sanskrit Panchatantra went into Syriac in the 6th century under the name Kalīlag wa-Dimnag, then into Middle Persian in the 6th century and into Arabic in the 8th century. From there, it fanned out across Greek, Persian and Hebrew, shedding its Hindu garb via Zoroastrianism for Islam and Christianity. John of Capua’s Latin Directorium Humanae Vitae carried the fables deep into Europe, although it seems that the Old Castilian rendering by the Toledo School of Translators in 1251 did come from Ibn al-Muqaffa’s Arabic. Its frame story gave weight to El Conde Lucanor (1335), one of the first works of Castilian prose.

Such avatars are classics in their own right. The 15th-century Persian Anvar-i Suhayli and the 16th-century Humayun-namah both became stock reading for princes. Nationalism borrowed Kalila and Dimna’s talking beasts in the 11th-century Persian national epic Shahnameh and, in the 20th century, when the Lebanese Marxist critic Husayn Muruwwa called them a yardstick of cultural unity. Kalila and Dimna made a handsome diplomatic gift for rulers across the Mediterranean, dittoed in lavish copies that still exist today. The stories wound up as a bedside book and teaching text so popular that the 18th-century Dutch orientalist Hendrik Albert Schultens dismissed them as schoolboy exercises. The poet and playwright Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was more charitable when he called them ‘writings of worldly wisdom’.

Scanning the landscape of Kalila and Dimna’s circulation, one wonders if Edgerton wasn’t on to something when he said only the Bible got more airtime. Baydaba’s fables appear as if out of nowhere and bob to the surface of history’s waters. The ‘Brahmin and the Mongoose’ story about the rash killing of a loyal animal ended up as a Welsh folk tale called ‘Llewellyn and his Dog Gelert’. The tales of ‘The Crow and the Snake’ and ‘The Heron and the Crab’ adorn Giuliano da Sangallo’s opulent staircase in the 15th-century Palazzo Gondi in Florence. The entire Kalilan corpus inspired Theodor Benfey’s 1859 theory of the Indian origins of all folktales, with the subcontinent as a kind of primordial soup from which all culture crawled to humanity’s shores.

‘Pondering on these facts,’ wrote the novelist Doris Lessing in her introduction to Ramsay Wood’s Kalila and Dimna: Fables of Friendship and Betrayal (1980), ‘leads to reflection on the fate of books, as chancy and unpredictable as that of people or nations.’ A strange quip about a work that seems practical and non-fatalistic. Then again, Lessing perfectly describes the reversal of fortune, the passing back and forth of glory, the ‘vexation of spirit’ in the words of Ecclesiastes. It’s one of the key themes that drive Kalila and Dimna.

Early on, we read about a whorehouse in which an ascetic, having nowhere else to go, lodges for the night. One of the prostitutes had fallen in love with a client and refused anyone else. Alarmed that this might cost her revenue, the establishment’s procuress tries to kill the client by getting him drunk and blowing poison into his anus with a reed. But at the moment of truth, the client farts in his sleep and drives the poison back into the procuress’ throat, killing her instantly. ‘The ascetic saw everything,’ states the narrative.