Some months ago I witnessed a scene from a revolution, though I didn’t recognise it at the time. I was in rural Lithuania, sitting in the dining room of a sprawling conference centre-cum-spa, a cavernous anodyne cube of mud-brown colours imbued with the vague fug of cigarette smoke. Not the likeliest setting for insurrection.

The revolutionaries were a cheerful assortment of writers, dancers, and other artistic types bent on nothing more daring than having a few drinks after a good day’s work. Most other patrons had finished their meals. It was late, and the cavernous room was otherwise empty save for a group of diners who sat two tables away. There were five of them: sharp-suited, stony-faced. Silent.

Russians.

Glances were exchanged within our group; sly smiles emerged, and there followed a noticeable increase in boisterousness, a slight notching up of the laughter; a subtly more frequent and assertive clinking of glasses in toast to our collective glory.

It quickly became too much for one Russian, who pointedly flung his soiled napkin onto the table in irritation. Our group quietened for a beat or two, precisely long enough for our rowdiest member, a bear-clown of a man called Petras, to give us all a healthy panto-sized wink… at which point it was all singing, all laughing, the bonhomie cranked up well past 11, until that inevitable moment when our Russian diners-in-arms glared at us in unison, stood up as one, and left the room altogether.

All revolutions have their peculiar recipes. Many require grievances and guns, while others hinge on the tipping of an historic weight over a seemingly ordinary moment: think Rosa Parks and a bus ride home from work. Some are won at the ballot box, others on the battlefield, while still more are driven between one and the other and back again.

The revolution now at play in Lithuania is like none of these: there are no bullets, no tanks, no secret police. The streets don’t seethe with unrest. The Lithuanian word that might best frame the heart of things is pasitikėjimas, which translates very roughly as ‘self-belief’ or ‘self-confidence’. This, I later understood, was part of what was happening in our dining-room standoff with the Russians: a simple assertion of place, presence and intention. We were having a good time, was the message. Who’s going to stop us?

But pasitikėjimas, like so much in the Lithuanian language — beloved of linguists for its uniquely close ties to Indo-European — has deeper layers. Its root, tikėjimas, is also used to convey passionate religious belief, or a connection to universal human feeling. Modern Lithuania is seeking not only to speak for itself as a unique culture — grumpy diners be damned — but to create a cultural opening for ideas, points of view and ways of ‘being’ not possible under Soviet rule. What’s happening in Lithuania, then, is a revolution of the soul.

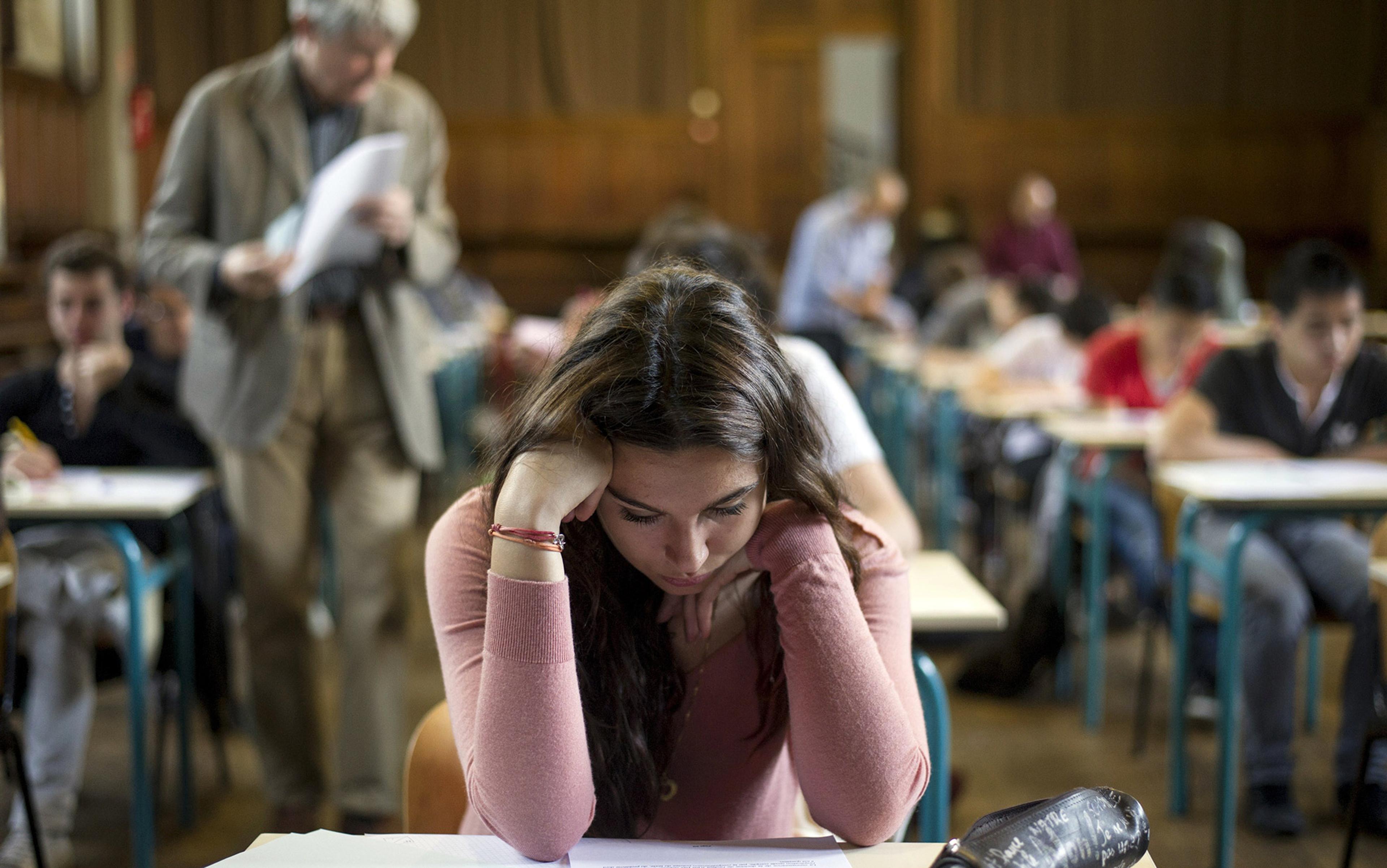

More surprising is the revolution’s weapon of choice: creative education. From 2012 through 2014, the Lithuanian government is backing a nationwide schools project designed to shake up the relationship between teachers and pupils, and between traditional and modern methods of teaching and learning. Lithuania does not do badly when it comes to basic educational indicators: its overall literacy rate, for instance, is higher than the UK’s. But most observers say that its schools merely emphasise rote memorisation over proper knowledge, and are primarily concerned with ensuring that children know their place. In class, questions are discouraged, noise is not allowed, and challenging the wisdom and authority of the teacher is unheard of.

The project intending to change all of that is an import, deriving from an ambitious UK schools reform programme called Creative Partnerships. Over the course of a decade, Creative Partnerships UK worked directly with more than 2,000 schools of every conceivable stripe — it was probably the largest single schools programme anywhere in the world focused directly on making learning more creative, both for teachers and pupils.

Schools are where a society is laid bare: its values, its aspirations and its cultural and political codes are visibly at work for all to see

Creative Partnerships matches schools with artists, scientists, designers, engineers and other ‘creative’ professionals. They work alongside teachers and with children, not so much to solve problems as to challenge assumptions. If boys aren’t interested in physics, for instance, what does interest them? Football, perhaps? Then why not devise a creative lesson exploring the physics of how a football moves around a pitch? (Through which one can explore the Magnus effect, velocity, gravity, drag, and any number of other essential concepts.) Dancers helping with maths; biologists animating the arts… Creative Partnerships revels in actively mixing together subjects, skills and ideas as a way of injecting more meaning, and enjoyment, into education.

In 2010, the incoming Tory-led government announced that it would terminate all funding for Creative Partnerships in Britain. Despite being widely praised across the political spectrum, Creative Partnerships was considered a Labour brainchild; no one was particularly surprised that it fell when the government changed. By that time, the programme’s director, Paul Collard, was speaking regularly to international audiences about the programme’s successes, often at the invitation of countries eager to infuse their schools with more creative practices. One such presentation, in March 2009, was in Prague.

At the time of the Prague conference, Milda Laužikaitė was a programme officer working in Vilnius for an organisation called Cultural Contact Point, a European Union-funded operation tasked with sleuthing out external ideas about culture and creativity and bringing them into Lithuania. Laužikaitė is tall and elegant, with sparkling blue eyes and a kind smile; much of the time, she has the air of a bright, well-organised graduate student. When she heard Collard’s speech in Prague, she knew she had found her calling.

‘We had been talking a lot about how so much of the dialogue around change in Lithuania is isolated,’ said Laužikaitė, now the Creative Partnerships programme director in Lithuania. ‘So many issues in the cultural sector, the arts sector, education, government, they have commonalities. But there is no synergy, which is something leftover from Soviet times.’

The phrase ‘Soviet times’ crops up again and again in conversations between foreigners and Lithuanians. This isn’t as inevitable as it might seem. Yes, Lithuania spent half a century under Soviet rule, but it was also the first Soviet republic to declare its independence, in March 1990, more than a year before the collapse of the USSR. Russians comprise only about five per cent of the population, compared with 25 per cent or more in neighbouring Estonia and Latvia, the two other Baltic states.

Yet, among these countries, it is Lithuania that most keenly feels the burden of its ‘Soviet times’. Part of this is structural: unlike neighbouring Estonia, which instituted radical free-market reforms upon independence — and in the process tipped the old Soviet system into the rubbish — Lithuania largely let its Soviet-style hierarchies drift forward unchanged into the 21st century. As a result, much of its society — not least its schools — retains a strong authoritarian flavour that many, including Laužikaitė, feel is a barrier to Lithuania’s attempts to fully establish itself as a modern, free-thinking, innovative country.

Laužikaitė is emblematic of a new and generally youthful generation of well-travelled, internationally focused Lithuanians: the first fully post-Soviet generation to reach influential adulthood. Despite their iPhones and smart clothes, this generation is not so much wanting to be Western as looking to find ways to use the best of the West to build a stronger, more purposeful sense of Lithuanian identity.

It is a sour experience of school, rather than a glowing memory, that seems to be a distinguishing characteristic for many Lithuanians

‘It’s difficult to make change because it’s a big system, one that is very set in its ways,’ she told me. ‘But when it comes to children, who doesn’t want to find ways to provide more quality, better ideas? Maybe, in that sense, it was the only place we could start.’

The Prague conference led to a pilot project in early 2011 to test whether a creativity-in-schools agenda might work in Lithuania. The pilot was brokered by Artūras Vasiliauskas, director of the British Council in Lithuania, which also provided funding. In the UK, Creative Partnerships proved particularly effective in re-engaging lost or nearly lost children: the ones for whom school becomes, very early, a drudgery rather than a springboard. Vasiliauskas sees himself in this description all too easily.

‘I attended school in deep Soviet times,’ he told me. ‘I was a very bad pupil, very unruly. I could not learn in that quiet, rote way. But there was one teacher; she always allowed us to make noise and to ask endless questions, which you never were allowed to do. I remember one lesson she said, “Go, all of you, walk into the forest and count how many steps there are to the lake, then come back and tell us.” It was at once a maths problem, a nature challenge and a social challenge. It was shockingly unusual, and of course I’ve never forgotten it.’

In many ways, special teacher stories like this are universal, at least in the West: think of a film such as Dead Poets Society or a novel such as To Sir, With Love. Yet it is a sour experience of school, rather than a glowing memory, that seems to be a distinguishing characteristic for many of the Lithuanians I’ve worked with. For some, participating in Creative Partnerships is a way to right a wrong. This can make for a bumpy ride. One practitioner, upon learning she was being assigned to work in her own elementary school, visibly paled at the prospect. ‘Oh no,’ she said weakly. ‘How I can go back in there?’

Having worked for many years as a practitioner and trainer in Creative Partnerships UK, I was asked, along with another colleague, to lead training for the Lithuanian programme. It isn’t uncommon for outside ‘creatives’ to work with children in schools, but Creative Partnerships asks artists — as well as scientists, engineers, and designers — to think of themselves as ‘creative practitioners’ rather than as professional specialists. The distinction is subtle yet critical.

A painter working in Creative Partnerships is not there to create great art or even to teach children basic artistic skills. Instead, painters are asked to apply their artistic intuition — those habits and skills that allow them to ‘see’ creatively — to deeper challenges such as absenteeism, poor academic performance, and behavioural problems. In this sense, practitioners are more like creative consultants: individuals with an outside eye who aren’t afraid to ruffle feathers or take on ossified tradition.

Philosophically, Creative Partnerships begins with the straightforward idea that teachers want to teach and children want to learn, but that too often other things interfere, the most common culprit being fixed ideas — among teachers, parents, even students — about how ‘learning’ happens. Experienced Creative Partnerships practitioners start small. Simply conducting a lesson outside of the classroom — in the sports hall, under a tree on the playground — can produce remarkably positive changes in student focus, just because it introduces novelty and curiosity. One looks for the slightest opening of a window through which new ideas might flow. It might be a throwaway comment by a teacher saying she’d found some new ways to talk to her students; it could be a single pupil who starts showing up in class rather than skipping school altogether.

Practitioners must tread deftly. Perhaps more than any other institution, schools are where a society is laid bare: its values, its aspirations and its cultural and political codes are visibly at work for all to see, for better or worse. Nonetheless, having worked with teachers, artists and students in six countries, I’ve found that some things are universal. Schools are places of constant change, yet can be deeply conservative — not least because they are the most regulated, structured, and procedural public spaces in any society. Even the tiniest change can have unpredictable ripple effects in terms of workload, curriculum, resources and the always-delicate relationship between teachers, pupils and parents.

Once you travel outside the vibrant, modern cities of Vilnius and Kaunas, it becomes starkly apparent just how delicate the balance of change and stability is in Lithuanian society. Scoured by glaciers, most of the countryside is pancake-flat and freckled with small lakes enveloped by oak-dominated forests. The country’s three million inhabitants are scattered across an area about the size of West Virginia, easily traversable between its furthest points in three hours or less. Many Creative Partnerships practitioners travel more than 100 miles to work in single-room schools in tiny hamlets where the internet is still a novelty. Some practitioners stay overnight in teachers’ homes or, in one case, in a tent at the school itself. Lingering prejudices and stereotypes — particularly around disability, sexual preference, and ethnic and racial difference — can be deeply confronting for modern urban professionals.

The Creative Partnerships programme in Lithuania will reach about 10 per cent of the nation’s schools, which makes it more of an experiment than a movement. The training has been emotionally charged, but usually in the best possible way: more than one practitioner has said that they feel a new power to make things change — by challenging assumptions, encouraging teachers and children to trust their creative intuition, and by helping to dismantle rigid structures within schools that are, after all, relics of a bygone era. New connections are being made, and there are the stirrings of new cultural enterprises with an eye towards applying the risk-taking, freethinking Creative Partnerships approach into other industries and to other environments.

Creative learning is often harder to grasp than the raw meat of test scores

‘Too often in Lithuania we think that change is not possible, or that it is up to someone else,’ said Vasiliauskas. ‘Most of the bottlenecks come from the communist period, especially the disbelief in change. It’s not so much the cultural character, but the social character. It’s how we’ve learned to behave and now we need to unlearn it.’

In July this year, Lithuania will assume the presidency of the European Union, a position that rotates every six months among the 27 EU member states. This is Lithuania’s first turn at the presidency, and also the first of any of the Baltic states. Though largely ceremonial, the EU presidency is a chance for the world to look anew at whichever state is holding the mantle. Lithuania will feel itself to be visibly on the world stage. Creative Partnerships is a good fit with an image that young Lithuanians want to project: forward-looking, proactive, modern.

When I last caught up with my friends who had driven our Russian dining companions out of the room, we gathered to watch a documentary photographic presentation from one of the school projects that had happened over the year. Creative learning is often harder to grasp than the raw meat of test scores, so it’s important to document what actually happens in the form of audio recordings, Q&As, scraps of drawing and writing, photos, videos… anything to try to encapsulate and make sense of creativity in action.

The project was elegantly simple: an elementary school class with literacy challenges was taken on a field trip into the local community, where a sound artist led them on a ‘listening journey’. After recording sounds and writing about them, the pupils wove them into a story that they told to teachers, other pupils and parents.

The benefit of exhaustive documentation is that, sometimes, you capture something wonderfully unexpected. The practitioners and teachers took hundreds of random photos of the listening project, and began to notice a particular pattern of activity involving one boy. In the first few photographs, the boy sits isolated at the side of the room while all other children engage enthusiastically with the project: making ‘listening devices’, mapping out their listening journey, creating their narrative. As the photos clicked on, the boy was gradually getting physically closer to other students; first observing, then assisting, then finally, participating. By the project’s end, he was standing in front of the class reading part of his group’s story aloud.

The boy was a native Russian-speaker, the only one in his class. He could not read or write Lithuanian and had been very withdrawn; the school was beginning to worry that it could not cater for him, and he was failing most of his studies. Subsequent to the project, his Lithuanian language skills improved markedly and he had become, by all accounts, a cheerful participant in the class.

There was silence among our group after seeing the photo series… and then, explosive applause and cheering. The pasitikėjimas revolution had taken another modest step forward.