With lockdown now as inevitable as death and taxes, our confinements have become as regular as the seasons. Like recidivists in and out of prison, we head through the revolving door, scarcely aware of direction or purpose. Beyond the challenges of provisioning and isolation, glued to our screens, we struggle to make sense of it all. How was it for you? And how will it be? A vacation from life, a foretaste of limbo, or a season in hell? Amid the welter of commentary – medical, political, and psychological – we hanker for a fresh view, an intervention from leftfield that might place things in a different light. In fact or imagination, we wonder, could things be otherwise? An anthropologist usually begins an enquiry by asking a philosophical question – what might it mean? – then, being of an empirical bent, looks abroad for alternative perspectives, different ways of framing or dissolving the problem. Under other skies, other answers.

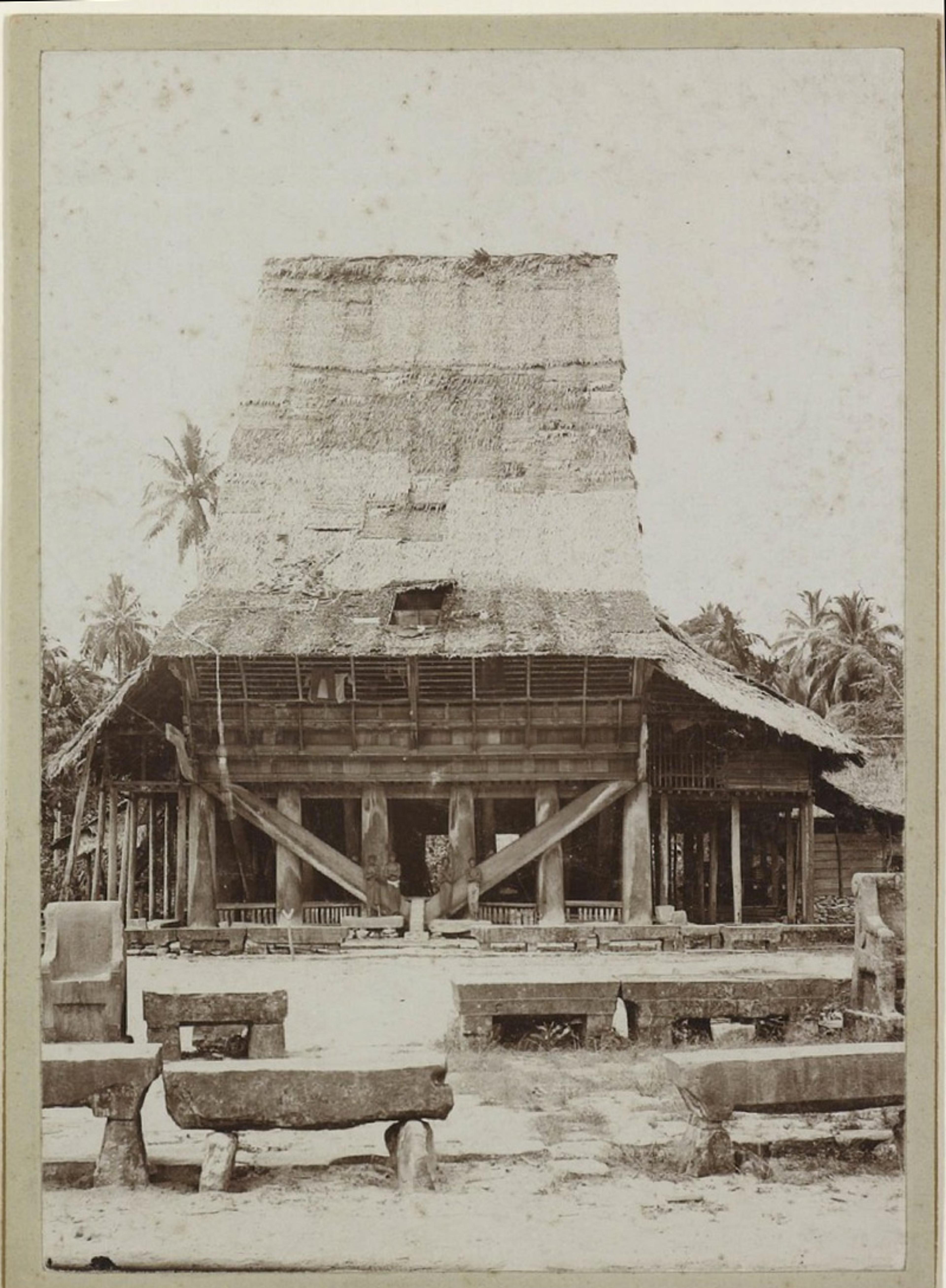

The Chief’s house on Telo Island, c1900, photographer unknown. Photo courtesy Museum Volkenkunde, Leiden, Netherlands

In Nias, an island in Indonesia, memories of the unrecorded past are inexact. The early 20th century, when the Dutch took power, is as hazy as myth. But once every couple of years, after the rice harvest, villagers would withdraw from society, out of the sun and the rain, the beat of field, forest and hamlet, for seclusion and idleness in the clan house: a ritual disinfection against the evils of the world. The crumbling, stone-paved square would fall silent; so, too, the facing rows of sturdy dwellings: longhouses raised on smooth boles with beetling, sago-thatched roofs and jutting, stepped facades like the sterns of ancient ships drawn up to a quay. When the curfew sounded, at a drum’s command, young and old climbed the creaking staircases, ducking through narrow doorways into gleaming, echoey halls empty of furniture, a communal airy space with dingy, cabin-like cells at the rear. As roof hatches were lowered and doors bolted, the trim, receding dwellings became arks, the outside world dropping away. With the house sealed against contagion and curse, and constituent families – half a dozen per lineage – quarantined between earth and sky six feet above the ground, the isolation was total. Each lineage, with its 40-odd crew, was cut off from its neighbours, afloat on a hilltop, deep in the forest. Such was lockdown in Tanö Niha, the Land of People (from niha meaning ‘person’, ‘human’, ‘Niasan’).

I’ve waited many years to make what would have once been a far-fetched comparison, a flight of fancy. Fieldwork in the 1980s, and again in 2011, couldn’t have suggested it. But reality has caught up. And midway through a third lockdown in the UK, the parallels are inescapable. As, of course, are the differences – though I begin to wonder about those too. Anthropology holds up a mirror to ourselves by considering forms of life alien to our beliefs and practices. Yet strangeness conceals deeper affinities. In the play of reflections and family resemblances, we glimpse ourselves in others, others in ourselves – a double-take as disturbing as it is illuminating. In the field – the anthropologist’s lab – our treasured verities get stretched and inverted, our shibboleths are shaken, our sense of human possibility enlarged. Distortion reveals the habitual in a new light. The effect is akin to what the Russian formalist critic Viktor Shklovsky in 1919 called ostranenie or ‘estrangement’, a literary technique of defamiliarisation exemplified in the work of Leo Tolstoy. Anthropology turns ostranenie into a vocation. As an ethnographer, immersed in another world, you shuttle between two conflicting ways of acting, thinking and feeling – torn, struggling, but living to tell the tale. From radical displacement, dépaysement, you construct a view of the world that’s true to your hosts, but born from yourself. The alien and familiar emerge as transformations of each other, variations on a theme. The Other is accepted, stranger and friend.

Here’s the challenge. That enigmatic sanctuary, high and dry in Tanö Niha, that home-bound exile, might tell us something general about the power of ritual, about purity and danger, the handling of risk, the bonds of community, or perhaps something vital about our common humanity. For we too, as fellow niha, connect to that faraway place.

At this distance, lockdown in Old Nias seems almost as remote to modern Niha as it does to us. Old-timers look back on their pre-Christian past, a time of raiding, headhunting and feasting that ended in the 1920s, with a mix of amusement and awe. Could we have done such peculiar, even terrible, things, they wonder, with a shake of the head?

Daily life, then as now, was a round of slash-and-burn clearing, the planting and harvesting of steep, rain-fed swiddens, and pig-herding in secretive backwood enclosures: an arduous rhythm punctuated by bouts of speechmaking and spectacular, reckless feasts attended by multitudes. This pendulum of plenty and poverty, scraping and splurge, stopped at a stroke when a village entered lockdown.

In the period of taboos, their healing touch was poison, their love a curse

Time-out had its own rules – not just an inversion of time-in, but a rigid protocol of Thou shalts and Thou shalt nots supervised and enforced by the ancestors, a ghostly mafia whose presence, not entirely beneficent, emanated from gaunt, sharp-faced figurines, ranged shoulder-to-shoulder along the roofbeams like shaggy crows roosting. The period of ritual separation, known as the Placing of Taboos (famongi), also had its own peculiar affects: an air of holiday jollity, a spirit of solidarity (‘one-heartedness’) that opposed the resentment and spite (‘painful heart’) believed to underlie everyday life. (An ethnographic trouvaille: feelings define spaces and mark boundaries.) Anyone outside the lineage was formally taboo, the object of suspicion and fear. Contact with unrelated folk, named ‘other people’, meant contamination and death, an insidious decline with a paradoxical, peppy prodromal phase (‘I feel fine!’) before the fatal symptoms appeared and you began to think back on whom you had seen, what you had touched. Was it that titbit passed on by a thoughtful neighbour? Or that night-time dash to the river for glutton’s relief? Was it something done or not done?

The interior of a typical Nias house. Photo supplied by the author

If ‘other people’ were polluting, in-laws – ‘those who are not other’ – were especially dangerous, precisely because, in the real world, they were regarded as the source of life and fertility. At the best of times, they required careful handling, a graded social distancing, a respectful flow of gifts. In the period of taboos, their healing touch was poison, their love a curse. For now, at least, they were safely holed up in their own clan houses. But no protective regime is watertight. As lockdown wore on and surveillance eased, lapses occurred, new threats emerged: matters for expert analysis, specialist jargon, tests (scrutiny of hens’ entrails), the incantation of formal admonitions to a docile, bewildered public.

So the ancestors had ordained it; and the ancestors, watchful embodiment of tradition, were still firmly in charge.

Sigmund Freud indelibly linked obsessive actions and religious practices, grounding ritualism in unspeakable anxiety. But the lockdown regimen in Nias had nothing of neurotic compulsiveness or the fact-mongering hypochondria of a public health briefing. Violence, disease and natural disaster were the order of things, not something you could hide from, still less repress. In the late 1980s when, with my wife, Mercedes Garcia de Oteyza, I carried out two years’ fieldwork in the central hills, it was still the case that half of all children died in infancy. Old people were few. Only the Indonesian region of Western New Guinea was poorer. And the sparsely populated interior had always been lawless, a human hunting ground. Until its gradual incorporation into the Dutch East Indies from 1908, the island was intermittently troubled by raiding and slaving. From headhunters, there was no immunity.

Yet aside from the steady risk of injury, disease and death – which went without saying – fears were limited and definite. German missionary letters at the turn of the century to reluctant donors in the Rhineland paint a picture of pillage and massacre. But outside of plagues and pest-induced famines, death counts were in single figures. Losses were mourned, revenge sworn, and gains totted up in a tight circle of tit-for-tat. The graph of grief was never exponential, the terror of total war and the savagery of the modern state unimaginable. Nias also had its unfair share of what we’d call natural adversities: earthquakes and tremors, epidemics, floods, crop blights, a panoply of tropical diseases (who nowadays remembers yaws?): some a gift of the gods, others the effect of sorcery, curses (those in-laws again) or ancestral displeasure. Tristes tropiques.

The bigger-scale afflictions were beyond human control, though some could be evaded, mitigated, or at least ‘understood’ because their causes were not, in Niha eyes, purely natural or material. Nothing is. The wrath of the gods, the angst of the ancestors, the malevolence of neighbours and rivals, could be blunted or assuaged. Lockdown was only a ramping up of ordinary ritual recourses, the top tier of graded interventions. An earlier generation of anthropologists, fearful of imputing irrational thinking to ‘the natives’, would have called the periodic withdrawal symbolic – without designs or efficacy, like modern prayers. But the symbolism of ritual can be more than an aesthetic frill; it’s a powerful tool, a technique of persuasion.

Which is why the Niha’s mania for numbers is illuminating. Whether in anecdote or swaggering oratory, Niha love to quote figures – so many heads, so many deaths, so many pigs slaughtered, so many ounces of gold. The recital of numbers is neither purely instrumental, geared to a utilitarian world, nor purely symbolic. It comprises a ledger of life, a sanguinary expense account that references a dense social history. This is true of any biometrics. Within a month of settling in the village of Orahua, I’d learned that our chief’s greatest feast involved the slaughter of 336 pigs over a period of nine days, distributed among hundreds of followers and rivals. I know it because he could – and occasionally did – account for every single one of them: who donated, who received, who still owed. I generally stopped him after Day One.

Lockdown was at once an ethical retreat and an opportunity to recalibrate the economy

What doesn’t show through Niha body counts and mortality rates is the spiritual-moral aspect, the affective penumbra that surrounds any reckoning of vital statistics and that clings, in our world, to what politicians trustingly call ‘the science’. In the daily updates of lives lost and saved, the league tables of death rates compiled by statisticians and pored over by pundits, every figure is freighted with hope, blame, fear, anger, shame, sometimes pride: a register of emotional investment. So it was in Nias, where, in the traditional calculus, heads taken and women stolen counted for spiritual merit as well as plunder. The taking of life was also an infusion of life, a cause for joy and matching grief. A raider’s trophies, of skulls and loot, burnished his warrior lustre. Life and death were finely balanced, and not merely as contraries, for each borrowed something from the other. In a culture preoccupied with just reckoning, measure for measure, things evened out; at least, that was the idea. In a wicked world, the interludes of house arrest helped restore the balance, calming the ship of state.

Lockdown was less a flight from reality than a stocktaking, at once an ethical retreat and an opportunity to recalibrate the economy. No less than in Calvinism (a soft option by Niha standards), ethics and exchange were logically linked, though the governing principle was reciprocity, not accumulation. After the lifting of taboos, with the slate wiped clean, weights and measures would be checked against standards kept by the chief or incised on his housepost, and rates of exchange between gold and pigs revised, with a lowering of interest on loans, from a ruinous 100 per cent (‘doubling’, the quickest route to slavery) down to a cautious 10 per cent. Between these times, through greed and ‘cheating at the mouth of the rice measure, fornicating in the fields’ (offences against fair dealing), equivalences between valuables would slide, causing imbalance and strife. Afflictions, heaven-sent or man-made, inevitably followed. Lockdown stopped all the clocks, setting off quarantine. Like any such suspension of normality, whether Passover, Lent or our current state of emergency, exit from quarantine was conditional on a comprehensive reset: in this case, a spiritual-cum-economic budget that would establish a new normal.

The last such reset I know about was in the early 1960s, when lockdown was no longer practised. Following a smallpox epidemic in which the chief of Orahua lost his wife and all six children, the elders convened an intervillage feast. Pigs were sacrificed, interest lowered, gold devalued. (In the days of full accounting, heads would have rolled – the heads of scapegoats, not offenders.) Chiefs from across the valley brought their bronze weights, had their gold-scales checked and their curly-handled measuring sticks reinscribed. On sunbleached flagstones, in the shadow of the chief’s house, an elder sang the Japanese imperial anthem – a memory of wartime occupation – as something suitably alien and authoritative. Locked out, snubbed by the new converts, the ancestors could no longer be invoked. Now Jehovah, if not Hirohito, was calling the shots.

After conversion to Christianity – not the religion of compassion, but a grim, deviant Lutheranism spread by wildhaired Niha prophets – what had formerly counted as sins against the ancestors became debts to God, to be redeemed in church donations or in frantic auctions that were almost bloodily competitive. On Sundays, each penitent brought a little quiver of leaves to church, a clutch of sins to be ‘paid off’ leaf by leaf. With the ancestors suppressed, the meaning of repentance was different but the metrics persisted. Numbers counted for everything because everything – life, sin, death, salvation – had a price. Not a market price, to be sure, but a reckoning of guilt, indebtedness for nurture, wifely labour or fertility, to be redeemed in gold and pigs at feasts – or, in the case of murder, weighed out in blood debt.

In that now-distant tribal society, on the eve of missionisation, Nias was still its own world, with its own manageable dangers, its known unknowns. Lockdown could still be meaningful, its goals – contain, mitigate, rebalance – were entirely achievable. Only in today’s runaway world is danger limitless and universal, the threat existential. Which makes the parallels both intriguing and deceptive. Like Niha, we scan proximate causes for ultimate reasons. We rely, helplessly, on expert advice. And like Niha we are conscious of having overstepped the bounds of what’s permissible. For them, the source of misfortune lay in a breach of reciprocity that disturbed the cosmic balance; for us, a different form of transgression, an aggravated exploitation, with what now seems an irreversible outcome. On the heels of the climate crisis – downgraded but not averted by lockdown, a dark cloud on the horizon – we sense we’re complicit in a great and ramifying crime against nature, a crime that our ancestors wouldn’t have understood and that cannot be redeemed. With a logic that Niha would understand, the pandemic seems like payback. We trust in science to deliver us from evil – as it surely will, until the next time. But our inconsistent efforts at ‘suppression, containment and mitigation’ often seem less utilitarian than performative; an affirmation that we’re doing (or not doing) something. That, also, Niha would understand. Indeed, when trouble looms, the technical quickly shades into the ritual: streets sprayed to gleaming sterility; coloured graphs endlessly retweeted; banks of tilting pipettes. Science fetishised.

A group of Nias warriors photographed in Orahili, Nias in 1875. Photographer unknown. Photo courtesy Museum Volkenkunde, Leiden.

Here parallel descends into parody, or perhaps bathos, the undertow of ostranenie. In the warrior culture that lingered in central Nias into the 1920s – within the living memory of my interlocutors – the prime threat, terrible but finite, was the raider. Men clad in crocodile-hide jackets, visors and half-masks with tusk-prostheses – a headhunter’s PPE – would attack at night, leaving footprints and a trail of blood. You couldn’t catch them, but you could follow them back to the source, scope their hamlet for moonlit reprisal. Track and trace. The shock of the raid, its horror-film staging, was in the advent: the flash of a sword in the dark, the tusked grin by firelight. Before you knew, it was over – and so, probably, were you. But revenge could be had. Risks were calculable. In contrast, the menace of spirits and sorcery, of contagion carried on the wind, was unquantifiable and implacable: the invisible worm that flies in the night. From that you could only withdraw.

Like any furlough, confinement had its upside. During our fieldwork in the 1980s, the few Niha who still remembered lockdown thought of it as a time of joy, of excess in the midst of austerity: ‘We were happy. It was all about prohibitions, but you had to be happy, that also was the rule.’ Provisions were stockpiled, firewood stacked around hearths, pigs corralled beneath the floor, their grunts and their sweetish stink rising through the boards. Here, in squalid isolation, life was simplified, kinship rekindled. Not just the nuclear family, but the larger lineage of like-minded and like-bodied: people like you, whom you took for granted in ordinary times.

Night and day, the carousing went on, as though the world outside no longer existed. Gongs swung from the rafters, men and women in gold regalia chanted to a drumbeat, girls danced hand in hand. At night, frolicking in the back rooms, laughter in the dark. Night work, they called it. But no proper work was permitted – nor ‘working from home’ – which meant most food had to be cooked beforehand. Sides of meat dangled from beams, a live-in larder, and anyone hungry just cut themselves a chunk. ‘You didn’t sweat for your meal; just ate your fill.’ By the end of confinement, the meat was green, rife with maggots, the smell unbearable, but there was nothing else to eat.

In its phasing and in its social expression, the COVID-19 crisis has many ritual aspects

Lockdown turned a bad world upside down. How else to set it right? Play replaced work, song speech, the home the field, days nights. You hardly knew when one day ran into the next, or where you ended and your fellows began. Distinctions of rank fell away, as did anger, spite and striving. Equality reigned. In lockdown, you entered the elemental human condition that Victor Turner, master of ritual theory, called communitas: a mode of relation characteristic of liminal zones and phases – boot camps, carnivals, initiation, the hajj – in which bonds are forged on the basis of unadorned humanity and in which feelings of mutuality prevail. There is no single word for this deeply felt connectedness, or the cluster of transformative emotions it engenders, but the anthropologist Alan Fiske, who has written extensively on the subject, uses the Sanskrit-derived formula kama muta for its myriad instances. Typically, kama muta is an intensification of what Fiske calls a ‘communal sharing relationship’. It’s a complex response unnamed in the lexicon (hence the neologism) and outside daily interaction, but that most people have known at some time in their lives. Many of us have experienced it under confinement, or witnessed it, and felt it empathetically, in the extraordinary medical dramas of salvation and self-sacrifice, devotion and gratitude centred on COVID-19 wards.

A characteristic of kama muta, like most emotions, is its transience. The feeling passes, the tendency to act – to step in and save, to embrace – fulfilled or resisted as circumstances change. But something persists. This was the great insight of the sociologist Émile Durkheim, who saw the ‘effervescence’ generated in collective ritual as fundamental to social solidarity and, ultimately, to the durability of formal social structures. In its phasing and in its social expression, the COVID-19 crisis has many ritual aspects: the shutdown of normality, the time-out for recreating family affection, the special garb and rules of engagement (social distancing, quarantine), the affirmation of central institutions as sacred, the moral triumph of ‘priestly’ doctors over secular leaders (note the contrast in demeanour, the medics stoical and upright, the politicians brazen or defensive), the revitalisation of ultimate values, the element of ordeal, and the assumption that we’ll come out of it different.

In the Niha version, kama muta had a memorable face. ‘My God, how we laughed! Our faces ached from it,’ as one veteran reminisced. ‘You were forced to smile, bound to love your kin.’ The laughs were long, but how long the quarantine lasted, nobody could quite remember. Suspended between earth and sky, life and death – longhouse limbo – that was also, somehow, the point. At the end – and, all agreed, it seemed endless – you were exhausted, partied out, sick of being happy. When the priests confirmed it was safe to go out – cautious checks, prognostications, scholarly disagreements, pompous formulae – you’d stumble into the daylight, filthy, slack-bodied, riddled with sores. Then it was down to the river to bathe and cast away all that was bad in a grand purification. The last laugh. A scape-pig tied to a banana trunk floated away, a white chicken’s neck was cut. And priests implored the ancestors: ‘Take your hands from our throats, fathers; let us live!’

In the early days of our our time in Nias – now our own prehistory – we heard much about a man called Amonita (‘Taboo’). Born during lockdown, around 1910, he belonged to the last generation to observe the prohibitions in full. That awe-inspiring moniker, a glorious stigma inflicted at birth, did him no harm. Like the ‘Boy named Sue’, he grew up to be a fearsome hard man, a valiant elder with numerous progeny, grand titles – Lord of the Masses, Feared by the Sun – and a feasting record to die for (which, in fact, he did, as the object of a sorcerer’s envy). But after conversion, with Amonita still hardly fledged, the old restrictions governing lockdown were banned. Taboos were taboo. As Christians, New People, Niha entered upon a strange kind of freedom entangled with new forms of restraint that were psychological, theological, vaguely oppressive. The old ritual solutions no longer applied. Anxiety never went away.

Amonita’s son, middle-aged when I knew him, became a close friend. Restless in his unbelief, sceptical of heaven, he struggled with the past and the undeclared pact of forgetting, a collective refusal of the past that was also a form of self-denial. In the attic of his modern Malay-style house (where I was billeted until my wife’s arrival) he kept a stone statue, a three-headed Cerberus, relic of the pagan era. He could neither throw it away nor accept it, so it lurked in the semi-darkness like a bad conscience, a dormant curse. Banished by missionaries, the ancestors and their absurd paraphernalia were an embarrassment, but they’d never really gone. You felt their influence in the sprouting of the crops, in the shivers of your fever, the bite of remorse. And that was his worry. The intricate mechanism of cause and effect, good and evil, prosperity and illness, was no longer comprehensible. The deep forest with its giant trees and shady solitudes had been stripped and the land half-ruined by new, pointless export crops such as patchouli (‘What is it for?) that left the soil barren. Pig plagues were a regular occurrence. So too were floods. What had caused the plight of modern Niha? Was it neglect of the ancestors, the lack of measure, the influx of wild spirits loosed by the retreating forest, or the ineradicable evil in men’s hearts? There had always been a way, a reckoning, a remedy. But for ‘we New People’, he agonised, ‘there is nothing. We here at the end of the earth are God’s stepchildren.’

When I returned in 2011, the village was greatly changed; in an expanded world, the island had shrunk. Even the leaping river, with its mantle of dawn mist, its deep pools and eddies, had shifted course, like much else after the earthquake and tsunami of 2004. Young people had fled the village for plantations in Sumatra. Orahua, half-empty, was as poor as ever, still without a light bulb, piped water or a road out. The chief’s great house, our former home, was now a skeletal hulk. Amonita’s son, God’s stepchild, had died, and links with the past, the Time of Joy, were almost broken. But when I played back a recording of chants made 23 years before, the old-timers joined in and the children danced.