I ask my sister how many years it’s been since the Taliban came. She says four years ago this summer. I say five. She insists on four and, with a laugh, tells me to count the months and then say how much time has passed. I look at the political map of Afghanistan before me, it has become a part of the wall. Sometimes I even forget that I’m staring at it. Tall mountains, blue skies bathed in sunshine and endless pain: that is my homeland.

I wish my arms were as wide as the sky so that I can hold my country and all its suffering in my embrace. Outside my room, doves have begun their afternoon flight. I head out onto the patio to watch them and wonder why I feel as if more time has passed since Kabul fell to the Taliban than actually has. Is it because every day since August 2021 has felt like a year? Or seemed as if it would never end? But even before then, the government was fighting a war with the Taliban that claimed lives every day. The wounds of my homeland are too many to number or to point out which ones have impacted me. They’re like live wires. Whichever one I touch shakes me violently.

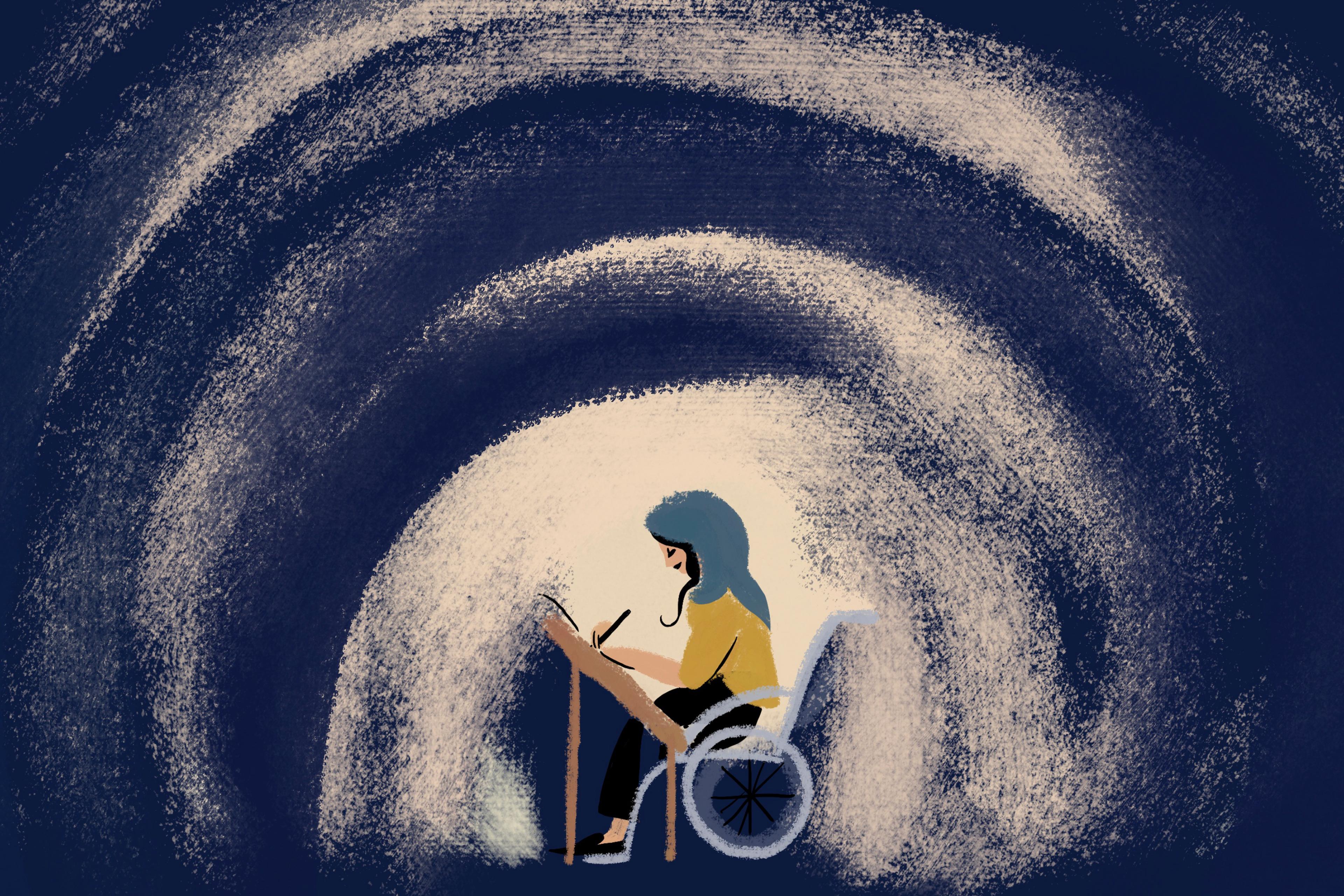

I’m 29 now, and I should have earned my master’s degree, but it remains a distant hope. I listen to the news and, when I get nauseous from the political games, escape into my novels: within their pages I find shelter from the bitterness of life. To keep a small light burning against the swallowing darkness, I also write, sometimes under a pen name and sometimes under my own.

I hold the hand of the writer within me tightly because I believe that more than any politician, it is this writer who will be of more use to my homeland.

So this is my story. This is how I remember the fall of Afghanistan.

Picture 1

It is 14 August 2021. I’m wearing black pants, a burgundy blouse with black stripes, and a thin crimson headscarf with my hair sticking out. I’m waiting for the elevator in my wheelchair and smiling at my reflection in the polished door frame. All around me, crowds of men and women are walking in great haste. I don’t remember ever seeing the campus so busy in my four years of studying at this university. Last night, one of the girls from the WhatsApp group of women activists I belong to messaged: ‘I have heard the president has resigned.’ When quizzed about it, she wouldn’t be drawn. However, social media is filled with lists showing the order in which the provinces will be handed over and reports on how the process is going. There seems to be an agreement to divide the provinces equally between the government and the Taliban.

That morning, on my way to university, I told my older brother Ali, who accompanies me wherever I need to go, that an interim government would be formed, a transitional government, similar to the six-month-long government formed in 2001, which preceded the US-backed Hamid Karzai winning the election. Like everyone else these days, I follow such things.

In the university hallway, I wait for two classmates whom I haven’t seen since our graduation last year. One of them turns up holding her purse and a book, the other clutches her mobile. Together we eat sweet summer fruits with Mr A, our former professor. Mr A spends the academic year here in Kabul, and the summer and winter breaks abroad with his wife and two children. Mr A introduces us to a young man called Saleh, who has up-to-date information about the political situation.

Both my friends are fervent about taking up arms to fight. I remain silent

‘The soldiers are surrendering territory after territory, there hasn’t been any fighting anywhere,’ says Saleh.

Mr A reacts angrily. ‘What idiots! Why are they listening to their chain of command? They must continue to resist! They have weapons and ammunition, don’t they? They mustn’t allow the Taliban to advance.’

Saleh says: ‘They hardly receive any weapons or ammunition in remote areas. The order for everyone is to surrender.’

When Saleh leaves, Mr A asks us what we plan to do if the Taliban come. Both my friends are fervent about taking up arms to fight. I remain silent. Peering at me over his reading glasses, Mr A says that I can fight the Taliban with the power of the pen – implying that I can’t fight with a gun because I am in a wheelchair. I still don’t answer and instead swallow the bite of honeydew melon in my mouth. I think, but I do not say: why should we take up arms in the country while Mr A’s daughter is busy playing the piano abroad? I think: what is the army for? Then: there’s no point talking about it because it’s already too late.

A few days earlier, another friend confidently told me there will be no armed confrontation in Kabul. ‘That’s what’s been agreed,’ he said. But people don’t trust the Taliban. They remember the harsh life ushered in under their previous rule, from 1996 to 2001, characterised by torture, humiliation and poverty. After being ousted by US-led forces in 2001, the Taliban fought to regain power and, every now and then, they carried out terrorist attacks on civilians. They claimed they were targeting foreign forces but, in reality, before every terrorist action, employees of foreign institutions received a message on their cell phones informing them of an impending attack. Both Afghan and foreign employees of these institutions had this advantage. But foreign forces aren’t present in universities or in marketplaces. Nor are they present in schools – especially girls’ schools, which were set on fire, while suicide bombers targeted the vehicles of civil servants on their way home from work.

Views differ as to what, if any agreement has been reached with the Taliban. Some say the government has been working on a peace process for years and that, as a result, the Taliban will no longer oppose women’s education and work. Others believe the United States and the Taliban have reached an agreement in Doha, whereby the Taliban takes over Afghanistan, while US and NATO forces withdraw. They say that to preserve its influence in Afghanistan, the US favours the Taliban over the Republican government.

The political realm is a place for jihadi leaders, drug traffickers and mafias

Knowing all this, I feel as if the whole country is slipping away, like sand held in my palm. As a former communist, Mr A opposes the Taliban and, sometimes, Muslims in general. He says the Taliban are few in number but organised, and this is their key to success. During my time as a student, whenever we discussed politics, Mr A would abandon caution and reveal his true beliefs to me. He encouraged all his students to join political parties, vote, and engage in social and political struggle.

Mr A is the kindest person ever to walk through the university’s doors. But he was not here in the mid-1990s, when civil war raged in Kabul, or for the five years following, when the Taliban took power. He does not understand that young people are barred from active participation in politics, and that the political realm is instead a place for jihadi leaders, drug traffickers and mafias. Mr A believes that a new generation must fight to take control of its destiny. Though I agreed with his views, I knew that the warlords and wealthy traffickers dominating parliament had to be removed before young people had any chance of taking control of their destiny. Unlike us, Mr A never had to get used to the repeated sound of bombs and artillery while hanging out with friends. Blam, blam! Boom, boom! Wham wham! Thoom thoom! Like a jingle. That’s why he didn’t understand us.

Picture 2

I’m wearing a pistachio-green flowy cotton dress. I have my hair tied up. I’m facing the trees outside the window and I have started my day. On the small table of my wheelchair are a few books and a mobile phone. I pick up my phone and read a message from my friend in our group chat. ‘The Taliban have reached the city gates.’

With my eyes wide with shock, I read this sentence out loud to my sister Meena several times. I still can’t believe it. It all seemed like rumours before.

Picture 3

People gather at our house. All my family members are present. Relatives we wouldn’t see even during the Eids arrive. A young girl in charge of the Daeshi women’s prison in Kabul comes straight from work to our house. We have many guests for lunch. The young girl says: ‘Whenever I go near the Daeshi women, some of whom are from European countries, they criticise the way I dress, saying my clothes are not like those of a Muslim woman; that my hair shouldn’t stick out from under my headscarf, and that I shouldn’t be wearing a blazer or pants. They think they’re going to save the world from oppression.’ Then she talks about which country will be the next superpower.

My family prefers to remain at home, not add to the sea of people behind the airport gates

Picture 4

Friends and relatives who are planning to leave the country stop by our house. They want us to go to the airport with them and get ourselves onto one of the planes bound for America, Germany or London. My uncle’s teenage daughter and son put on their backpacks and bid us farewell. They put water bottles and some biscuits in their backpacks and set off to join the multitudes of people outside the airport. They will try their luck. After several attempts, they manage to leave the country.

A distant female relative who is equally desperate to leave, forces her husband and five children to go to the airport with her. Under the Taliban’s previous rule, she couldn’t attend school or realise her dream of becoming a filmmaker. Memories from 20 years ago are etched in everyone’s memory: floggings, public executions, the repression of women, imprisonment for making trivial personal choices, and worse than that: the image of Syria and the calamity that Daesh brought upon it is in front of everyone’s eyes when they say Kabul is no longer a place to live.

My family prefers to remain at home, not add to the sea of people behind the airport gates. We will leave the country once things have calmed down. It’s a difficult moment for us, when everyone is leaving and we feel the urge to follow. But it’s not clear who is making the right choice.

Picture 5

At night, seeing videos of people getting trampled and screaming at the airport gates affects me so deeply that I get nauseous and stay that way for weeks.

Picture 6

Moonlit summer nights and the sound of gunfire.

Picture 7

The sound of military planes. Practically falling out of bed, thinking that a plane has crashed in our yard. Sleeping with the sound of bullets being fired at civilians.

We are all sitting together under the grapevine when we hear an intense explosion

Picture 8

After foreign forces withdrew and the crowds of people behind the airport gates melted away, flights out of the country ground to a halt. Everything fell silent. One could hear the flapping of birds’ wings, and sadness was the dominant colour of those days. I felt as if the whole world was like Kabul; that no one was happy, and no planes could fly to other countries. It was strange for me to see on social media that people around the world went about their days as usual. How could people carry on with their lives while all this was happening? All of this was exploding in my head because Kabul was in my heart. Its grief hurt me deeply. The silence of those lonely days was unfamiliar. A cold and sunless place.

Picture 9

Sunday, 29 August 2021. It’s late afternoon, and my older sister, two brothers and I head over to our grandfather’s house, which is one street away from ours. We are all sitting together under the grapevine when we hear an intense explosion. Its crack and shudder terrify us. Later, we find out that the sound, so unlike the sound of the usual rockets, was a US drone strike on a residential area nearby. It turns out that the drone operators thought a house in the area belonged to the people who organised the 26 August attack on the airport, but they are wrong. What if this mistake had been made about our house? The thought makes me feel unsafe, even in my own bedroom.

Picture 10

One summer’s night in 1998, my grandmother wakes in the middle of the night. She drinks a glass of water. Notes the sound of an approaching car coming from the street below. It stops. She draws the curtain and peers down from the second floor to see armed men looking for someone or someplace. The men notice the drawn curtain and realise that someone is secretly watching them from the window of the residential house in front of them. They get near their Datsun. Look up at the window again. The woman stands her ground behind the slightly drawn curtain and stays there for so long that the armed men become anxious and leave.

In October 2021, my friend Zahra, a storywriter, posted a video on a WhatsApp group that showed the Taliban searching houses on her street. Zahra looked like someone on the run. She had her backpack on and was ready to abscond before the Taliban reached her house. I wrote to tell her that she was like my grandmother, a woman who stared at Taliban fighters from behind the window in another time. Why is history repeating itself? How much longer must the women of my country experience this fear?

Perhaps the resistance of women will make the Taliban change their mind

This is what I wrote to Zahra via WhatsApp:

On a summer night in 1998, my grandmother wakes up in the middle of the night. She drinks a glass of water. Notes the sound of an approaching car coming from the street below. It stops. She draws the curtain and peers down from the second floor to see armed men looking for someone or someplace. The men notice the drawn curtain and realise that someone is secretly watching them from the window of the residential house in front of them. They hover near their Datsun, uncertain. Look up at the window again. The woman stands her ground behind the slightly drawn curtain and stays there for so long that the armed men become anxious and leave.

At the end of my message, I added:

Perhaps the resistance of women will make the Taliban change their mind and force them to stop imposing their restrictions on women.

Picture 11

Kabul is shrouded in November darkness and at 8 pm nobody can be seen outside. At this hour, my family and I are returning from a dinner party at my uncle’s house – even our dinners have to end earlier, because the streets are so dangerous at night. There is no official curfew, but after years of living with insecurity, people have learned how to protect themselves. Since the Taliban fighters wear the same clothes as ordinary people, any rogue can pretend to be a member of the Taliban and kidnap or rob someone.

Before the Taliban took power, people enjoyed the city’s nightlife; they’d frequent restaurants, shops and entertainment spots, staying long after midnight. But in the three months since the government changed hands, no one dares keep their shop or restaurant open late. Everyone turns off the lights and goes home. When the city is enveloped in darkness, anyone in a car can be stopped and searched. The Taliban are primarily searching for soldiers of the former government and anyone with ties to the National Resistance Front. It is not immediately clear whether the man in civilian clothing, standing in the middle of the road and pointing his flashlight at us and ordering us to stop, is a Taliban member, a passerby or a bandit. He shines his torch into our car, blinding us. If we had met him or people like him before the transition in August, we would have expected nothing but a bullet and death. These Taliban faithful were the ones who would cut off your head if you were travelling from one province to another and they found out that you worked for the government or a foreign institution, or sometimes simply if you were Hazara.

I don’t know how to tell him that this might not be the end of their friendship

Picture 12

In September 2021, when normal life returned, schools, businesses and banks all reopened. But not everyone resumed their lives. Teenage girls were still barred from attending school, and women who worked in government and non-government offices were told to stay home. On 17 September, an official order issued to girls in years 7 to 12 informed them that their schools would close until ‘further notice’. Many girls went to school nonetheless, but they weren’t allowed to sit in their classrooms, and their teachers told them to go home. The autumn days went by without the girls of our near and far-off neighbours passing by the trees at the back of our street on their way to school. When winter came, these girls went to school to get their long-awaited exam results, but they returned home empty handed, without the new books they were supposed to get for the next grade.

Picture 13

My brother Ali leans with his shoulder against the window, staring at the elm tree. He tells me: ‘Bilal is gone too, he left with his parents to join his older brother and sisters in America. But for now, until their American visas arrive, they went to Iran.’ Bilal and Ali were childhood friends. They were the same age and met when my family first moved to this street. Bilal was the son of the neighbours across from us. Outside the window, the wind is blowing and several leaves fall from the tree. I ask: ‘Really? They left today?’ He says: ‘They left two days ago: Bilal messaged me this morning to say they’d reached Tehran and rented a house there.’ Ali looks at the tree with perplexed eyes. His feeling of loneliness spreads to me. I don’t know how to tell him that they might still see each other again and that this might not be the end of their friendship. Ali says: ‘How nice it would have been to grow old with our friends in our homeland.’

Picture 14

After the restrictions on women’s dress were imposed, my sister Sara, who is three years younger than me, went to university dressed from head to toe in black. My grandmother always forbade us from wearing black because all grandmothers believe that black is the colour of misfortune. They’d say that no happy person should wear black, as the person’s luck changes depending on the colour they pay the most attention to, or wear. But I, who have read the renowned debate between night and day written hundreds of years ago by the Sufi mystic Khwaja Abdullah, am not too pessimistic about the colour black. In that debate, the night defends its darkness and says to the day: ‘If I’m black, so is the Kaaba, so are the eyes of the lover that makes everyone fall in love with them.’ I’m only sad that everyone has to wear a certain colour at the behest of others.

Picture 15

Since I couldn’t enrol for a master’s degree, I pulled all my law books about the penal code and principles of litigation off the shelves, put them in a box, and took them down to the basement. All my plans were ruined.

Picture 16

A sunny winter day, 7 February 2021. At the invitation of a civil society organisation, I attend a conference at the Kabul Serena Hotel. Several young girls are tasked with asking all the guests which NGO or government institution invited them, telling them to write their names on a list and sign it. In the main hall, I see guests both young and old, Afghan and European. All the European women are wearing headscarves. On every table there are fresh roses and programme booklets with the conference title: ‘Women’s Initiative for Peace and Security’. I flip through the programme. Two middle-aged women next to me are having a conversation about sending their children abroad. The young girl across the table from me looks familiar; she has a big smile on her face and her earrings are swaying. Locks of hair peek out from under her beautiful headscarf. There are several people here whom I’ve seen only on television.

With my eyes, I ask her if she has written the novel she promised to write

I am not interested in any of the speakers, or even the most popular female members of the House of Representatives (Wolesi Jirga). The only person I’d like to meet when I spy her across the room is Najiba Ayubi, the head of the Killid media group. I spent my childhood years reading weekly stories in her magazine. I call one of the waiters to help me and take me to her, but another online guest starts their speech. Headphones are handed out to those who can’t understand English. I take a pair. Ayubi looks at me from afar. I think to myself that my wheelchair probably caught her attention. With my eyes, I ask her if she has written the novel she promised to write. Of course, she did not promise me personally; she’d simply said so in the introduction to her collection of short stories. Maybe she has forgotten her promise. She’s giving me sincere smiles from afar. As a writer and activist, she too gives a speech. The conference ends with the promise that in their peace talks with the Taliban, civil society organisations and EU member states will advocate for the preservation of achievements women have made over the past 20 years.

Picture 17

NATO forces and foreign organisations are given just 16 days to leave the country, along with Afghans in their employ who could apply for asylum in the West. After the US Air Force C-17 Globemaster boarded 823 Afghan women, men and children into the cargo section of the transport plane and took off for Doha, others began demanding flights out, swarming the airport gates and climbing onto the wings of aeroplanes. People had lost the will to live and the hope of staying alive. Everyone figured that, if people were being evacuated this way, then very bad things were going to happen, and that it was imperative to save their lives and those of their families. Everyone was rushing towards the airport, and Daesh used the opportunity to send a suicide bomber who detonated himself among the crowds. A few days later, on 30 August 2021, Daesh fired several rockets at the airport. The sound of the rockets piercing the air was clear and sharp. They were intercepted by US air defence systems. The sound of them exploding was terrifying.

I feel as if, at any moment, a rocket will be launched from an unknown place and end my life. Even watching the sunset and the flight of the doves can’t rid me of this fear.

Picture 18

Reading various social, cultural and political histories of Afghanistan and the world always encouraged me to take part in political and social activities. Taking to the streets to protest and call for greater justice and security was important to me. I thought that we were slowly making progress, which meant kindling a light that would never fade.

I vowed to save this writer self so that she could document everything she witnessed

I was a supporter of the National Congress Party, a federalist party that discussed everything that was forbidden, from the US occupation of Afghanistan to questioning the monopoly of power held by certain groups. I thought about formally joining the Party. At university, I would debate with my professors and classmates whether federalism was good for Afghanistan or if it would only increase chaos and ethnic and linguistic discrimination. Federalism was and is an important cause for me. Still, I worried that the warlords, who were already ruling for themselves, could declare absolute monarchies in their states if a federal government was formed.

When the Taliban arrived, I realised that, in truth, the fate of my homeland lay in the hands of America and its puppet politicians. I abandoned any thought of joining the Party because all its leaders and members had left the country. Instead, I became more familiar with the writer in me. I vowed to save this writer self so that she could document everything she witnessed.

Picture 19

Before the Taliban banned women from attending university in December 2022, I went looking for Mr A. One of the janitors told me: ‘He left Kabul the same day the Taliban entered the city,’ adding, ‘Mr B, Mr S, and several others who had second passports also left that day.’ He laughed, adjusted his pakol hat slightly to the side, and walked toward the garden. Then he turned to me, and said: ‘They still haven’t paid us these past few months’ salaries.’ All the professors who’d taught us about social and political struggle and encouraged young people to rise up against social inequalities had hastily left the country. I felt like a person in the middle of a fleeing crowd, with everyone’s shoulders slamming into mine.

Picture 20

The day the Taliban entered the city, I gave up reading books and started following the news instead. I’d sit all day and think about why my country had never experienced prosperity and never would. It felt as though Afghanistan was handicapped and wheelchair-bound like me – unable to stand on its own two feet.

I would listen to the political analysts, waiting to hear something positive about my country’s situation, but none said what I needed to hear. I wanted them to say that Afghanistan is the most resilient country in the world; that it can overcome its political and social challenges; that Afghanistan has gone through many crises and will overcome this one as well. I wanted to hear them say that Afghanistan is important to the world and cannot be ignored.

I found in its pages someone just like me, their homeland destroyed and their compatriots exhausted by war

When I looked at my bookshelf, I searched for books that understood me – that were as hopeless and grieving as I was. But I couldn’t find one. I regretted lending Margaret Mitchell’s novel Gone with the Wind (1936) to a friend. I longed to read it again and remind myself that war had existed elsewhere in the world as well. I didn’t care about where, or at what juncture in history the book was set, I just wanted to find someone whose life was destroyed and whose country was in ruins, so I would know I was not alone.

I remembered that the Kurdish writer Bachtyar Ali, whose country was also engulfed in war, had written a novel called The Last Pomegranate Tree (2002). Perhaps this book would comfort my heart and ease my mind. And so, after 20 days, I finally opened a book and found in its pages someone just like me, whose life was full of suffering, war, disability and loneliness, their homeland destroyed and their compatriots exhausted by war.

Picture 21

My younger sister Sara was engaged. She’d wanted to put off her wedding until after her graduation. She was still studying when the Taliban returned to power. Her final year was 2022 and, after she sat her final exam on 18 December, they banned girls from attending university. Sara was unable to get her diploma or any other document proving that she had finished her studies.

That same winter, her wedding took place in a large wedding venue, attended by all our near and distant relatives. Women danced in a separate hall that no man was permitted to enter. Some guests we’d invited didn’t come, and those who did brought their anxieties with them: they wanted to forget their hardships by participating in a joyous occasion. Sara glowed in her white wedding dress, stepping into her new life in the depth of winter’s darkness.

Picture 22

Headlines in the local news filtered into local gossip; the stories we heard from friends and relatives all said the same thing: the Taliban were forcibly marrying young girls, and if anyone resisted they were imprisoned or killed. A friend of mine called me with concern after her neighbour’s daughter was married in this way. The girl had been taken to the Gulbahar Centre, a residential and commercial complex in Kabul, where she lived alongside other girls who shared a similar fate, and their Taliban husbands.

I am so overwhelmed by the chaos that I’d forgotten that girls and boys are still in love with each other

Political developments in Afghanistan have always been like this. When power changes hands, so does the fate of the people. No government cares about the wellbeing of the population, only to consolidate its power, even if it comes at the cost of thousands of lives. Many people have lost their jobs and fled the country. Others have stayed, knowing the Taliban was not going to harm them: they only had to give up their government posts to Taliban members.

Under these conditions, I am surprised to see my younger brother post a poem for his girlfriend on a WhatsApp story. I am so overwhelmed by the chaos that I’d forgotten that young girls and boys are still in love with each other, and that the hardships the girls are going through worry their lovers the most.

Picture 23

I opened a WhatsApp story posted by my friend, who wrote: ‘How good do these Taliban commanders look in Afghan clothes [the perahan tunban and the lungi]. They are very formidable.’ I thought to myself that whoever holds the power becomes attractive to the public.

Picture 24

A bookshop in my neighbourhood, Zaryab Press, is one of the best in Kabul. A small yet beautiful and useful shop. I can forget all my worldly worries there. It is filled floor to ceiling with books. There, I not only lose my wheelchair but I even grow wings.

I wait for the elevator on the ground floor with my younger brother Poya, who is still in high school. I think that maybe the repairman has fixed the lift this time and I will be able to use it. But the lift isn’t working and there’s no one to help us up the stairs. A few people pass us by with studied indifference. Finally, my brother goes to seek out the owner and ask for help. The bookseller knows that his regular customer is in a wheelchair and, together with my brother, he lifts my wheelchair up the stairs. I look at the books, thumb through their pages. I show the bookseller screenshots of several book covers I’ve seen on Instagram, and my heart sinks with every book he tells me has sold out. Still, I buy so many other books that it is hard for me to hold them. Every few seconds, I tell my brother to push the wheelchair slowly so they won’t fall out of my hands. I pay a lot of money for them and feel ashamed that other people don’t have food to eat and yet I buy books.

The Taliban dictates every aspect of our lives, even if we can meet friends or what relationships we maintain

Picture 25

I’m meeting two of my friends: a girl around my age (I was then 25), who still wore trousers and a blouse with her usual headscarf, and a boy from Panjshir, dressed in black from head to toe. His face is clean-shaven. When I tell him that the Panjshir front has collapsed, he puts his hands in his pockets, lowers his head, and whispers: ‘Some people among the Panjshiris were of the same mind as the Taliban. They worked with them and passed on information.’ The three of us sit in the university garden. The gardener who used to smile at us whenever he saw us there as students, seeing a boy and girl sitting and talking together approaches us and says: ‘Go and sit somewhere, out of sight of the Taliban post so that they won’t bother you or make trouble for us.’ He keeps on apologising. It’s troubling that the Taliban dictates every aspect of our lives, even deciding if we can meet friends or what relationships we maintain.

Picture 26

The smoke rising from our neighbour’s chimney, and I, suffering from coronavirus.

Picture 27

The café where I used to drink lemon and honey tea with my brother Ali closes down. Ali would always order a bitter coffee, while I would stare at the lemonade seller next to the big elm tree as he filled the summer days with the fresh scent of lemon.

Picture 28

It was a sunny Friday in Kabul, 30 September 2022. The sky was clear and a light breeze was blowing, the weather as kind as it could be. I was sitting in my room, writing on my laptop. At one point, I took a selfie and posted it on my WhatsApp status. My friends showered me with heart emojis. I had many texts, and among them, in a WhatsApp group of writers, someone mentioned that the Kaaj educational centre had been attacked. I Googled the chilling news. Fridays are holidays in Kabul and no one goes to work or educational centres. Instead, families visit parks, throw parties or take trips to the outskirts of the city. But the young girls and boys at the Kaaj centre were preparing for their Kankor exam (a national university entrance exam) and had gone to study on their only day off. Since hearing of the attack at 11 am, I have been rooted to the spot.

People were invited to fill the library’s shelves in honour of the murdered students

This wasn’t the first time I’d heard of a suicide bombing or explosion targeting civilians; it wasn’t even the first time I’d heard about students being killed, but death is not something you get used to and it shocks me every time. I removed my story from WhatsApp because I didn’t feel like being merry with my friends anymore. Though sunlight flooded my eyes, everything looked grey. In the evening, my mother asked me why I hadn’t finished my dinner. I told her I had no appetite. I’d read the death toll from the Kaaj bombing had reached 45. My younger brother who was also preparing for the Kankor exam, said: ‘Our educational centre has also been threatened.’ Days like this remind us that living in Kabul is like being on the front line.

A library was later built in memory of the fallen students. People were invited to fill the library’s shelves in honour of the murdered, most of whom were from poor Hazara families. My sister and I pulled together 60 of our best books: War and Peace, Anna Karenina, Rousseau’s Confessions, The Brothers Karamazov, a collection of poems by Qahar Asi, a poet who was himself killed 30 years back in the civil war. The library manager, a mere youth, came to our house and collected the books. Kaaj, which means pine tree, an evergreen and a symbol of steadfastness, had become a bitter memory piercing our souls.

Picture 29

As if obsessed, I read Qahar Asi’s poem ‘How Wound Upon Wound Are You, Kabul’ all day long. Asi was a young poet who emigrated to Iran during the civil war of 1992-96. He was welcomed there warmly as a Persian poet but he couldn’t bear to be away from Kabul and returned. He lived only a few months after his return. At the beginning of autumn, the same season in which he was born, he was killed by a rocket.

Picture 30

It is the summer of 1973. My grandfather and his friend go to a restaurant to celebrate fixing his friend’s car. The waiter puts their food on the table. They listen to live music. Outside, a handful of cars are moving on the street. At the sound of the explosion, all the windows shatter. My grandfather and his friend flee the restaurant. The car that they’d just had repaired is sprayed with bullets before their eyes and so they leave it there with its broken windows and take a taxi home. Neither of them knows what happened. Afterwards, they learn that a cousin of Mohammad Zahir Shah, the last king of Afghanistan, staged a coup to end Zahir Shah’s 40-year reign and formed a new government, calling it a republic and naming himself its ‘leader’.

Picture 31

I purchase a 10-volume collection of Anton Chekhov’s stories and letters and start to read it. It helps me begin to feel better. It is as if Chekhov is talking to me directly, telling me his tales and silencing the devastation around me. I laugh at the things he wrote to his brother or friends, and admire how subtly he used humour.

Picture 32

The quinces hanging from the tree branch.

My head spins and my heart beats fast. This is yet another case of suicide that I hear about following recent changes

Picture 33

After the Taliban seized power, many people who had left Afghanistan came back to visit their families once the bombings and suicide attacks had abated. One of them was my uncle. My father’s family, like most Afghan families, was large; my grandfather had seven sons and a daughter, and this was my youngest uncle. He was my good friend. Before going to America, he would always come and check on me. If I needed help getting from my wheelchair to my bed or into the car, he’d jump to. He used to take me outside and put my legs in the sunlight, hoping that I would get better. He’d brew green tea with cardamom, make us burgers, and tell me stories from his childhood. He read my fortune through Hafiz’s Book of Divination and, on the day he left for America, I gave him that book to remember me by. We’d endured five years of separation before he returned.

Picture 34

Poya, who is 16, enters my room, his face drained of colour. He says: ‘This morning, on the street above ours, in a building under construction opposite the school, a young worker who had come from Samangan province hanged himself.’ My head spins and my heart beats fast. This is yet another case of suicide that I hear about following recent changes. The entire place is deserted. The streets are empty. Many people have lost their jobs, and many of those still working have not received their salaries. Four months have passed since the government changed, and winter is upon us. Perhaps that young worker who took his life had been suffering for a long time, and this was the final blow to his shattered hopes. Is this the end of all hope?

Picture 35

My mother wants me to go inside so I don’t catch a cold. But I am sitting outside so that the cold winter winds will blow away my troubles and the pearly clouds and flying doves will fill my heart.

Picture 36

Ali is once again staring at the trees that are now leafless as he tells me about another close friend who is leaving the country. This friend was his classmate at university and, in all their gatherings, his presence would complete the group. His family went to Uganda and planned to travel to America from there. I didn’t have any words to comfort Ali. Let him face this reality and this loneliness and not be afraid. What can I say? That he can make new and better friends? All the friends with whom he drank tea and coffee every evening or on Fridays have left Kabul. The coloured paper kite that’s stuck on the branch of the quince tree is shaking in the wind.

Picture 37

Meena, who is two years older than me and studied economics, is teaching Hafiz’s poems at the madrasa. She barely managed to convince the principal to let her do this, as it’s not allowed. The students have been told not to talk about it outside of the madrasa.

If we spend Nowruz happy and surrounded by family, we will be happy and with our family until the end of the year

Picture 38

In February 2022, the Taliban began conducting house-to-house searches in Kabul. They were looking for weapons and documents that proved that a person had worked for the previous government or a foreign institution. They made exceptions for UN staff, but that was it. Anyone who had a contract, a photograph or any other document showing they’d once worked in the government or for an NGO had to destroy it. I did the same. Before the search came to our door, I threw the printed contracts for my stories into the flames of our heater. At that moment, I felt like I was destroying my past, my memories and everything that was dear to me.

Picture 39

The Solar New Year arrives on 21 March, and every year we celebrate Nowruz – the first day of the year that also falls on the first day of spring. We prepare an offering called samanak, which is made from sprouted wheat paste, flour and water, and haft mewa, a combination of seven dried fruits like oleaster and raisins, and nuts like almonds and pistachios, which are put in water to become sweetened. My grandmother always says that, whatever we do on this day, we will do for the rest of the year. So if we spend Nowruz happy and surrounded by family, we will be happy and with our family until the end of the year. This is why my mother always makes sabzi (spinach) with rice and all kinds of special food on the eve of Nowruz, and none of us are allowed to be outside or go to parties. But on 21 March 2022, after the Taliban cancelled public celebrations of Nowruz, my younger brother took his books and went to school.

Picture 40

After one year of Taliban rule, the street lights are on again at 1 am and the streets are once more full of cars. Even my family, who have forgotten this face of the city, feel the situation has improved. The people of Kabul, though still afraid, have become somewhat used to seeing the Taliban in the city. I get a message on WhatsApp from my friend, a public school teacher. ‘Why are you still awake?’ she asks. ‘The fear of my salary decreasing has kept me awake. It will be winter again, what should I do?’ The Taliban have allowed some women to return to their government jobs on the condition that they do the same amount of work for lower salaries. Others have been told to say home. They receive paltry salaries to do nothing.

Picture 41

Before the fall of Kabul, our neighbours’ daughters used to blast happy music at full volume and dance to it. In Kabul, no neighbour tells another that the sound of their radio is too loud or that the sound of children playing, screaming and shouting is annoying. When women laugh, talk to each other or speak loudly on the phone, the sounds go from one courtyard to another, and this is normal. But when the Taliban arrived, they made playing all types of music illegal. The girls stopped dancing. Only once in a while would a song get loud before being quickly shut off, indicating that someone’s father or mother had put a stop to it so that it wouldn’t cause trouble for them.

What hasn’t changed are the killings, explosions and clashes by various groups who oppose the Taliban

Picture 42

Ever since the Taliban arrived, emigration has been on the rise. Many people who’ve lost jobs have to sell all their household belongings to avoid facing poverty, or else they’re selling up before leaving the country. Every day, scrap dealers roam the streets of Kabul, shouting that they will buy household items if anyone wants to sell them. My mobile’s contact list is full of numbers that no longer work because their owners have left.

What hasn’t changed are the killings, explosions and clashes unleashed by various groups who oppose the Taliban and that take place in different parts of the city. My family, having chosen to stay, has also faced more financial problems than before. We had to let go of our housekeeper as we couldn’t pay her monthly salary. My mother does all the housework by herself and I am sad to see her work so hard. While I read a book in my wheelchair, I keep looking at the clock but, without really seeing the time, I take my eyes off it. Then I remember once again that I want to know what time it is, so I look at the wall clock again, and once more I forget what time it is.

Picture 43

My mother made an offering so that all her children would be blessed and healthy. She put wheat seeds on metal trays and watered them for 15 days until they grew green. Then she cut the wheatgrass with scissors and squeezed the paste from the sprouted wheat using a juicer. She cooked it with flour and water in a large pot over the fire for 12 hours. At last, the samanak is ready. If my grandmother hadn’t migrated to Pakistan with my aunt, she would have been singing around the samanak pot and playing the dayereh – a traditional frame drum. She plays it so beautifully that last year all the women in the neighbourhood climbed up onto the rooftops to listen to her sing. This year, we sit alone by the samanak pot, without anyone to sing for us.

Picture 44

The first time I went to the nearby hospital, after August 2021, there was a Taliban Ford Ranger parked outside its gate. I am not a member of the basketball team because I can’t move my hands well enough, but I have friends there and I go to watch their matches. My friends believed that the car was there to keep an eye on the hospital, so that they didn’t contravene any Taliban rulings. My friend, who’s able to move around deftly in a sports wheelchair, threw the ball towards the net then came to me. She said: ‘We come here every day and practise in the name of physiotherapy; if the Taliban found out, they wouldn’t allow us to come.’

Picture 45

I am tired of sitting at home and miss going out with my brothers. Since parks and gardens are no longer open to families, we go to a restaurant. Many families are there; the women and girls wearing black chapan coats, in a way that hides their colourful blouses and jeans. And all the women are accompanied by their husbands or fathers, or, like me, by their brothers. Most women glance at me as I sit in my wheelchair, and when our eyes meet, they smile. The men keep stealing curious looks, too. Stories flow loudly from every table. At one time, you’d hear music instead. Indian, Iranian and modern Afghan songs. Sometimes a customer would connect their phone to the restaurant’s loudspeaker and everyone would listen to their song.

Returning home, we spot the white-clothed inspectors of the Taliban’s Vice and Virtue squad standing on the side of the road and stopping any car with a woman inside. They warn the women – and their menfolk – to pay attention to the way they dress: their clothes should not be short, tight or Western in style, like pants. They ask passengers how they are related to each other. And tell them to turn off any music playing in the car. They stop our car too. Ali gets out and explains to the Taliban member that I am his sister. The agent looks at me again and admonishes me for sitting in the front seat. From now on, I must sit in the back.

Looking back on the last few years, it saddens me to report that life under Taliban rule is fraught with hardship and injustice. From the type of clothes women are permitted to wear to the back seats we take in the car and elsewhere – everything is dictated by a government that denies us even the smallest bit of personal freedom. Every effort at self-improvement made by women and the younger generation has come to a stop. I have witnessed countless women drift into the depths of depression or become immobilised by anxiety, and this is something I experience myself, too; the only difference between us is that I write secretly, and have continued to do so throughout these years of Taliban rule. My dream of pursuing a master’s degree still burns in my heart, pulling in both joy and despair.

I don’t mind the bedsores; for a while, I might even forget the wounds that I endure from sitting in my wheelchair. It troubles me more that my life no longer has direction and I don’t see a future before me. Who isn’t afraid of walking in the dark? The young generation and the women of Afghanistan pursue their dreams by every possible means, even in secret. Girls go to madrasas to study; they learn mathematics and literature, poetry and painting, and some manage to leave the country to continue their education. Yet there are still women, too young or too defeated to face the hardships imposed on them, who surrender and become exactly what the government wants them to be: young, illiterate mothers who don’t know how to take care of themselves and their children.

I wanted to see women walking in the city and feeling safe. I wanted the sounds of explosions to be only of joy

It no longer matters whether a woman is physically healthy or disabled; Taliban laws have kept everyone from participating in society. These days, the women and children of my homeland risk their lives crossing mountains and rivers with their families – the women handing over money they’ve earned through long years of hard work to human traffickers who promise to take them to lands free of darkness. The hope is that they will end up in a place where their fate may be certain, but so often they are either killed or thrown into border prisons or drowned in the rivers.

I wished none of this for myself or the people of my homeland. I wanted Afghanistan to be a place with the best welfare system in the region for citizens with disabilities, because long wars have demanded sacrifices from people’s very bodies. I wanted to see women walking in the city and feeling safe. I wanted Hindus and Muslims to live peacefully alongside each other once again. I wanted the sounds of explosions to be only of joy.

The sun has set and the doves have now returned to their homes after being released for a few hours to fly around in the sky above our neighbourhood. Night has fallen, and with a heavy sense of failure, despair, fear, desire and exhaustion, I return to my room. Moths fly in the courtyard and fill the air. I look at the distant houses on top of the Badam Bagh hill and along the Khair Khana Pass. Their lights are still on. I think to myself: beneath the suffocating darkness of the night, it is hard to believe that tomorrow the sun will rise again from behind these mountains.

This piece was made possible by the Bagri Creative Writing Award, a partnership between Untold Narratives and the Bagri Foundation to support Afghan women writers in the Paranda group.