The year I graduated from the university, I married a man, J, whom I had known for two years. Some of my friends thought it was too soon, especially as he was not ‘from here’. My father wondered if I had thought it through, marrying a foreigner. I said I had. When J wanted to go home to Belgium not long after we got married, it did not devastate me. I did not spend days trying to convince him to change his mind, or negotiating how often we would have to return to Nigeria on holiday. I did not once doubt that I would go with him.

I had never been to Belgium and I remember asking him when we first got together if he did not miss Bulgaria. I kept getting the two countries mixed up, not only because I was bad at geography, but because neither was on my radar of places to move to after graduation. My older siblings were in the US and in the UK. And I had never thought that if I left Nigeria it would be to any place other than these. Yet when he said he was going ‘home’, I did not hesitate to pack up and go with him.

I did not care whether it was Bulgaria or Belgium. I was certain that I would love it and make it mine too, for the simple reason that it was his. Moreover, I did not mind veering off the beaten path. Armed with a brand-new degree from one of the top universities in Nigeria then, and an arsenal of phrases from a Teach Yourself Dutch book, I was confident that the only way to go was up. I was eager to begin writing this new chapter of my life.

A new country. New friends. I did not think then of my leaving as leaving ‘home’ but as a going ‘home’ for, already in my mind, I had replaced Nigeria with Belgium as home. When well-meaning friends asked me if I would not miss ‘home’, I assured them that my ‘home’ was wherever J was and so what was there to miss? Besides, apart from being born with a peripatetic itch that needed scratching, I wanted to see where he was from, meet his people, start a family.

J’s family lived in Turnhout, Flanders, a little town shaped like a dog standing on its hind legs, where he was born and raised. And so it was only logical to move to Turnhout and begin our new life there. At first, we lived with his parents while we settled in and he looked for a job. I discovered quickly that migration goes hand in hand with a peculiar kind of loneliness that not even fresh love can dispel. I also discovered that my upper second-class BA from a Nigerian university was not impressive enough to get me a job.

Nothing I knew before seemed to be of consequence. Not language. Not social etiquette

Four years later, with a postgraduate degree from a Belgian university, I went to an employment office to register for work. Without asking for my qualifications, the lady at the counter smiled brightly and offered me a job on the spot. ‘We need cleaners, you can start today.’ Her smile slipped when I assured her that I needed a cleaner more than she did. ‘If you do find one, please send them to me,’ I told her.

But that was in the future, after I had regained my voice.

In that first month of my migration, I was busy losing my voice in small imperceptible ways. I was finding out that nothing I knew before seemed to be of consequence. Not language. Not social etiquette. The first morning at his parents’ house, J woke me up to have breakfast. I was not hungry and I told him as much. ‘No, darling,’ he said. ‘Everybody is at the table. They are waiting for you.’ ‘Why?’ I found it baffling that I would be required to come down to breakfast — whether I was hungry or not — and certainly did not understand why anyone would wait for me before eating.

Back home in Enugu in southeastern Nigeria, I ate whenever I was hungry. We had a gigantic dining table in the living room but we rarely used it and certainly not all nine of us at the same time. The last time I remember the entire family sitting around it together (minus my dad who had escaped to Osumenyi, our ancestral home) was when my mother made us all sit there for a lunch for my ninth birthday — for the benefit of the video camera recording the events of the day. I still have the video and when I watch it, it strikes me how unnatural it looked, all of us around the table, eating at the same time, trying to pretend that the camera was not fixed on us. For sure, I had a few friends in Nigeria who used their dining table more often than we did, but I do not recollect that they made a compulsory occasion of it, every single day. ‘Besides,’ I said, ‘I still have to take a bath.’ We could never eat at home without first taking a bath. It was considered impolite. ‘You don’t need to bath. Here, take a bath robe. It’d be impolite for you to be late.’ That was my first lesson in re-defining the parameters of politeness.

The time staying with my in-laws was a lesson on how to navigate the social waters of my new home. Everything was regimented: breakfast at 8am, dinner at 12pm and supper at 6pm. If one planned to miss any meal, one was expected to give notice. You could not sit in front of the TV with your dinner. No TV when there were visitors. Dinner was a ritual. Table set. Soup. Main dish. Dessert. Polite conversation running through the meal. I found it rather tedious, all the rules to abide by, teaching my palate to appreciate an alien cuisine, trying to follow a conversation I had no chance of understanding. Everything was strange. Not even the hot chocolate tasted like the one I was used to. Coffee: Black. No milk. No sugar. More bitter than the instant coffee I drank during exams at university to keep from sleeping when I ought to be studying. The bananas: perfect-looking, like plastic fruit but lacking the rich, sweet taste of the mottled bananas I bought in huge quantities back in Nigeria.

My parents-in-law spoke very little English and my Dutch was limited to the phrases the Teach Yourself book had assured me I needed to survive the country. ‘What time is it?’ ‘When does the train leave?’ ‘Where is the post office?’ Phrases so useless in company that I felt for the first time what it must be like to be deaf and dumb, but without the privilege of knowing sign language. Sometimes, J’s siblings or aunts and uncles joined us for dinner, and J tried to drag me into the conversation by translating for me, but it was not enough. It could never be enough. Often, caught up in the excitement of the conversation, he forgot midway that he had been translating, that I could not follow without his help, and threw himself into the dialogue. I did not want him to worry about me and so I learnt to make myself so small that I became invisible. I hid my face in the soup bowl and polished off my plate. I learnt to smile whenever anyone looked at me. It was a wide, brittle smile. A smile of straw, and I had to pay attention that it did not break.

The sixth of seven children, I was ill-equipped to deal with solitude. Our house in Enugu was always full of people

Unable to make J’s home mine, I missed home more than ever, even the things that had irritated me back in Enugu. I missed the noise of traffic outside my bedroom window; the early morning bell-ringing, itinerant preachers by whom I set my clock; the heat which often sent me scampering for an air-conditioned room. I found this place too quiet, too cold. It often felt as if I had walked into a freezer. Or into a mortuary for the living. I missed being among the familiar. Being where I was not conscious of making a cultural faux pas; where I was not pretending to enjoy the meal. Where I could hold a conversation. Argue. Debate. I had always found consolation in writing poetry, and wrote a lot as a boarder 1,000km away from home. As an undergraduate, I had published a collection of poems, Tear Drops (1993). Yet now, I found it impossible to write. The Muse abandoned me to face this future on my own. I felt betrayed.

Two months later, we moved into our own home, a rather charming small house near the chest of the dog. I was certain, now I could make my own rules, that I would be happier and the Muse would be enticed to return. I looked forward to abandoning my smile of straw, to making forays into the city centre, window shopping, meeting new people, eating out, writing a new collection of poems inspired by all the new experiences. I had visions of making friends as good as the ones I left behind. Women with whom I could talk about books and clothes and life and poetry. In the first week at the new house, I went out once on my own. I smiled at every black face I saw. I entered shops and touched clothes I had no intention of buying.

When I was ready to return home, I realised I could not find my way back. I have always had a terrible sense of orientation but on that day, it appeared to have been magnified. I took one wrong turn after another, and when I decided that I needed help, no one spoke English. Finally, after what seemed like hours of aimlessly walking around narrow streets, sheer luck delivered me to a bakery I recognised. It was the bakery at the beginning of the street where I lived. I was grateful to be home but my gratitude at making it home, in hindsight, was exaggerated. My sense of direction, poor to the point of being ridiculous, had always been a source of mirth, and I had thought this could make a funny anecdote to share at the dinner table. But this time, I found that I could not share it with J. I was more shaken by the experience than I thought I would be. The tightness that had grabbed hold of my chest when I was lost did not ease with my getting home. I became too frightened to leave the house on my own.

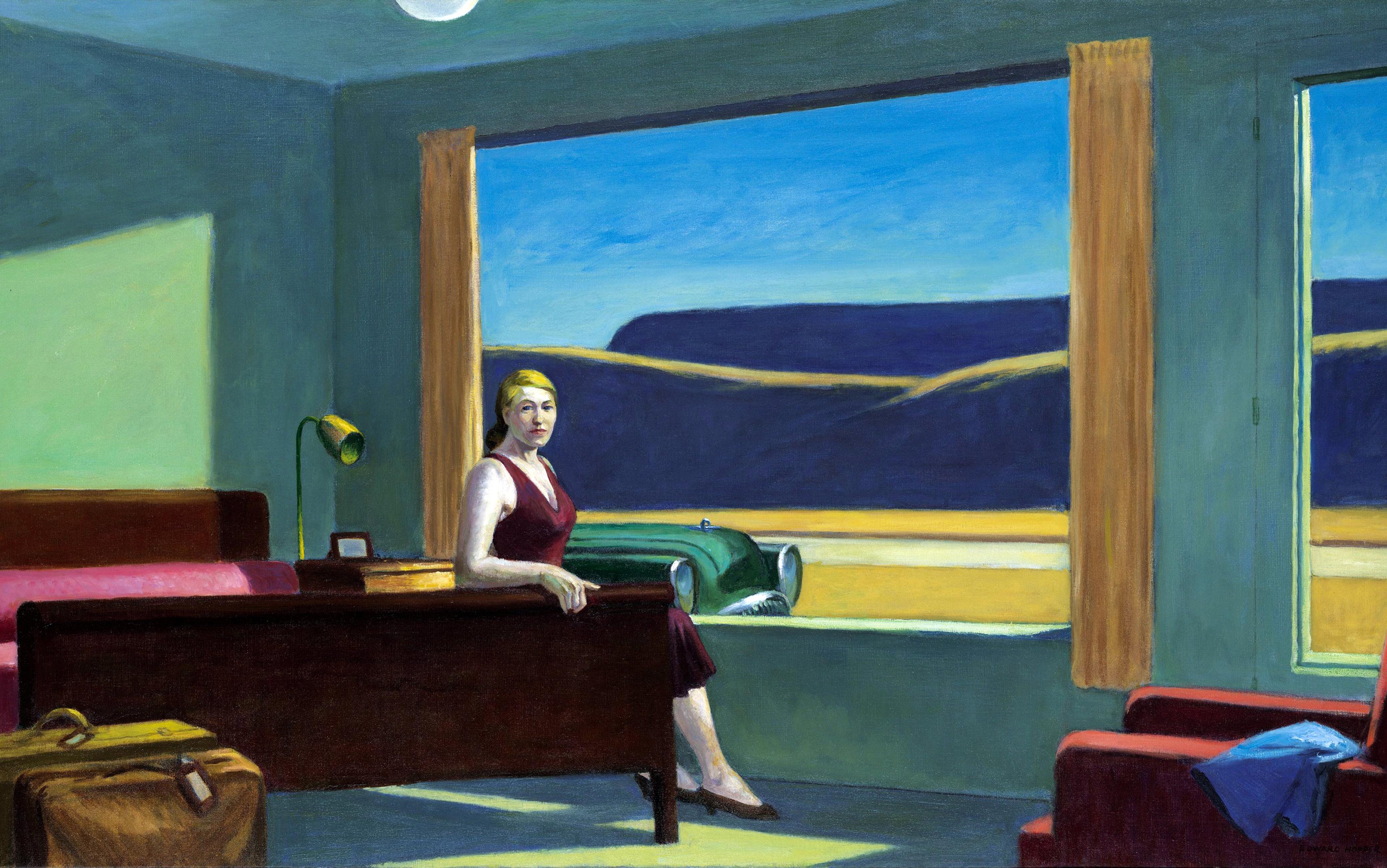

In this state of partial immobility, my homesickness deepened. I could feel it lodged deep inside my stomach. It was like a huge stone weighing me down. I had nightmares of this stone pulverising me. Now that I needed it more than ever, my Muse refused to come. By this time, J had a job he was excited about and was away working until 6pm. I woke up with him, but went back to bed as soon as he drove out of the house. I stayed in bed all day refusing to get the door or answer the phone if it rang. I suffered panic attacks and imagined that I was dying. It was the darkest period of my life, and I could not convert it into art no matter how hard I tried.

‘Yes! Excellent idea.’ My voice felt garroted but my wide smile was easy to summon

I became adept at putting on a happy face around the time J came in from work. The smile of straw stayed. I listened to him talk about his colleagues, his day, and I envied him enormously. I envied him almost to the point of resentment. He had a life. I had none. It seemed like I was sealed in a box with no way of getting either light or air. I came up for air only when J came back from work and brought in a bit of the outside world with him. But whenever he was gone, I wondered if love was enough. I asked myself if I had the courage to admit that this had failed and that I wanted to go home. But when he asked how my day had been, if I had been anywhere nice, I lied. He thought I was having tea in town. Going window shopping. I do not know why I lied. Sometimes, I think I did it to protect him from the darkness that was engulfing me. At other times, I am convinced I did it out of vanity. I did not want him to see how vulnerable I was, to see how the confident, young woman he had married was failing to hold it together in a new country.

One of the things that had drawn him to me, he told me soon after we met, was my ‘stunning confidence’. He said he had never met anyone quite as confident as I was. Having lost that confidence, I was unwilling to let him see it. And so I persisted in my lie. When an aunt of his who lived not too far asked him why I never came to the door when she rang during the day, J repeated my lie of me being out and about, enjoying the sights Turnhout had to offer. He made jokes about me never being home, said how happy he was that I was adjusting well to Turnhout. It was impossible to let him in on my secret, for both our sakes.

I have never been good with solitude. The sixth of seven children, I was ill-equipped to deal with it. Our house in Enugu was always full of people. Even after my oldest siblings left home, there were cousins and friends who stayed for any length of time. I am not one of those writers who work better behind closed doors with not a soul anywhere near them. Place Obioma (what I call my dependable laptop) and me in a café with customers chatting in a background and I thrive. The more alone I felt, the more lethargic I became. It was a vicious circle. I did not eat because I had no appetite. The stone in my stomach had grown to take up all the space in me so that no food could get in. It took most of my voice so I spoke very little. J had always enjoyed cooking, and would cook once he got in from work. I pretended that I had made something huge for myself during the day, or invented something I had eaten in town. I would eat a little to please him, finding no pleasure in it.

At the weekend, we took drives into other parts of Belgium. Brugge. Gent. Antwerp. Cities with a lot to recommend them. It was the only time I left the house. Like a needy two-year-old, I would not venture away from him. We took carriage rides like tourists at my insistence. Determined to show him I was having a good time, I insisted on having pictures taken with every monument he pointed out to me. The son of a history teacher, he had inherited his father’s love of history, and so would give me historical facts about every building he pointed out. I feigned interest but barely heard him. The stone took all of my attention. In all the pictures from those days, my smile is too wide, my eyes alarmed. In some of the pictures, I am clutching my stomach. To anyone looking at me, I might have been clutching it from too much laughter. Pain is easy to hide if you try hard enough. I learnt that in those months.

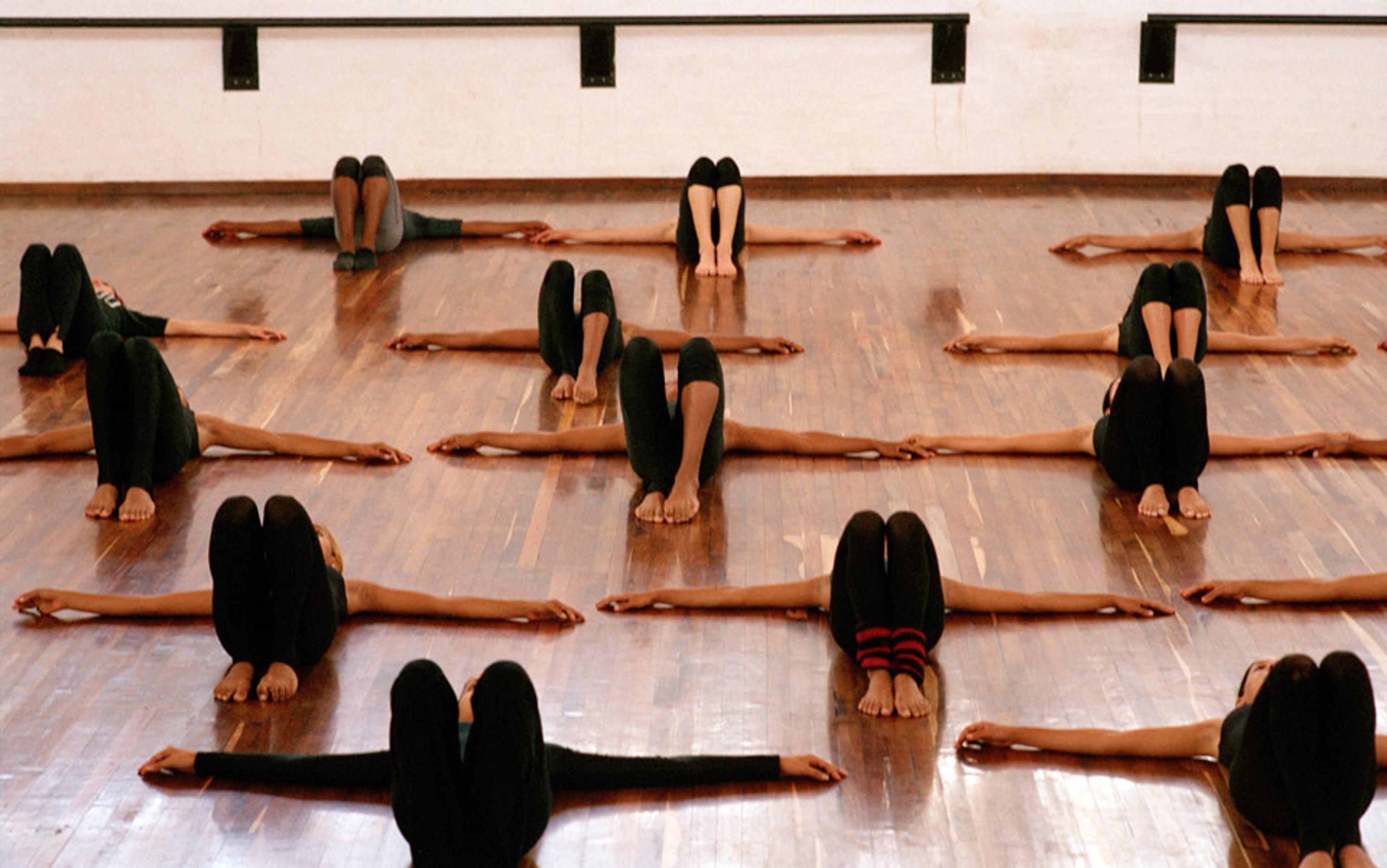

That summer, four months after my migration, J suggested that I start intensive Dutch lessons at the university. They had a really good programme, he said. He had learnt Italian there in his second year before going as an Erasmus student to Milan for a year. ‘You’ll learn Dutch there in a short time.’ I had heard enough Dutch to know that that was an impossibility. It seemed to me to be a language with no rules and with completely unpronounceable words. I was also apprehensive about leaving my safety net. I did not know if I could muster the strength to get up in the morning and catch the train to the University of Leuven. But I had no choice. I could not tell J that I would not go. What reason would I give? I did not want to raise his suspicions and so I feigned enthusiasm. ‘Yes! Excellent idea.’ My voice felt garroted but my wide smile was easy to summon. I allowed J to accompany me to the school to register at the language centre.

That became my saving grace. The seven hours I spent in class each day, with other newcomers, trying to come to grips with this guttural language, which sometimes sounded deceptively like English but that made no sense at all, began to pay off. I learnt the proper way to pronounce huis (house) and ga (go), my biggest challenges. One day at a time, my vocabulary expanded. Dutch was no longer a great intimidating unknown. When we visited J’s family, I could decipher the words. I could say how my day had been. The more familiar the language became, the more the stone shrank, a little at a time, until I no longer felt the weight of it. Until forays into town were no longer the stuff of my imagination. And I began to make the kind of friends I had always imagined I would. And my smile of straw disappeared. And only then was I free to write again. Not poetry. The Muse, alas, never returned, but fiction came in its stead.

When I began to write again, I discovered that I was not writing the kind of fiction I would have written back home. Certainly not at first. I wrote about displacement and sorrow. The voices of immigrants filled my head and spilled out on several pages of short stories and then a novel, The Phoenix. My characters were mostly melancholic women unable to return home but lacking the tools (or perhaps the temperament) to fit into their new home. They were victims browbeaten into silence by an alien culture and an alien climate. Perhaps it was me wanting to pass on what I had suffered to someone else. Maybe it is human nature to seek revenge even when there is none to be sought.

A few years later, the Muse allowed me progress to the stories of ‘comfortable’ immigrants: characters who have learnt to efficiently carve a place of comfort for themselves abroad, even if they dream of returning home at some point. The women of On Black Sisters Street have a certain joie de vivre which my earlier characters lacked. By the time I started work on my third novel, I had served as a city councillor, I had taught in a school, I was sufficiently at home in Belgium for my imagination to be given the freedom to return home to Nigeria. I like to think of Night Dancer as symptomatic of me completely regaining my voice. The Muse may lead where it will, but I am no longer just putty in her hands.