Live in a city long enough and you can complete very substantial journeys on foot, broken into many hundreds of instalments, all out of order. Take the example of the line of main roads through London – including Whitechapel Road, Cheapside and Oxford Street – that runs from Stratford in the east, to Shepherd’s Bush in the west, a distance of just over 10 miles. This is one of London’s most important and ancient axial routes, roughly following the line of a Roman through-road. I’ve spent a great deal of my life living on or near this stretch, and my grandmother and my wife’s family live near it, and have done for decades. It is the spine of everything I know about London – as it must be for thousands of people.

Although I know every yard of that 10 miles, until last year I had never experienced it as a whole. Last year, I was studying for a postgraduate degree in Architecture at the University of East London, a course with a particular focus on the mutations of late-capitalist London. For an end-of-term assignment, we were set an interesting task: to undertake a long walk to serve as the basis of an essay examining the use of the dérive as a tool of urban criticism. I decided to walk from Stratford to Shepherd’s Bush, pleased by an accidental symmetry: I would be walking from one Westfield mega-mall to another, joining two peripheral, centrifugal sites to the city’s centre of gravity.

Urban criticism was the intended purpose of the dérive, as imagined by its inventor, Situationism’s chief founding-father Guy Debord. The dérive, which roughly translates as ‘drift’, was an artistic reaction to post-war capitalism, as it was expressed in urban planning. Its chief target was the modernist planner, personified by the Swiss architect Le Corbusier, and his dreams of comprehensive redevelopment; but it was also aimed against Baron Haussmann’s monumental 19th-century rebuilding of Paris as a series of imperial set-pieces designed for police and artillery action.

What Debord and his followers particularly abhorred was functional zoning. In the 1930s, Le Corbusier and the other modernists who composed the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne imagined the chaotic, dirty Victorian city reconstructed as an orderly machine, with specialised zones for work, habitation and recreation joined by efficient circulation. The Situationists thought this model, embraced by both organised capital and organised labour, repurposed the city as a tool of total control and social conditioning. Instead of existence, there was work: instead of leisure, consumption. ‘Everyday life was cut up and laid out on the site to be put together again like the pieces of a puzzle,’ wrote Henri Lefebvre in 1968.

The dérive acted as a way of thwarting the functionalist vivisection of the city, breaking across the boundaries of those planned zones in an unplanned way, treating the city as a disorderly continuum rather than an orderly series of components. It is an urban walk, performed consciously, and breaking with the normal patterns of daily life. As Debord says in Theory of the Dérive (1956):

One or more persons engaging in dérive give up, for a greater or lesser duration, their familiar reasons for movement and action, their own acquaintances, jobs, and forms of leisure, to release themselves to the solicitations of the site and of the encounters suiting it. The place of the aleatory here is less determinant than is thought: from the point of view of dérive, there is a psychogeographic relief of cities, with constant currents, fixed points, and vortexes that make approaching or exiting certain zones very difficult.

‘Aleatory’ is the role played by chance in the composition of music or poetry. The point is not to wander aimlessly, but to identify the fixed flows and gravity-wells of the city, in particular those imposed from above, and work against them. Instead, you pay attention to the street and listen to what it tells you – an interaction that rarely happens when it is treated as a sluice of pure circulation between functional poles.

The dérive became the basis of ‘psychogeography’, which in recent years has become a literary cottage industry in the UK. My personal introduction to it came in 1999, on precisely the axis I would later walk. I was living in the basement of my grandparents’ house in Holland Park at the time, looking for work in journalism after leaving university. Often, I would go to the Waterstone’s on Notting Hill Gate and browse, usually without buying. But one day I came across a small, cheap, new book by an author whose name dimly rang a bell. This was Iain Sinclair’s Sorry Meniscus (1999), a long essay about trying to walk to the Millennium Dome – first published as two separate essays in the London Review of Books.

I found it a remarkable piece of prose, and read it two or three times back to back. It described a city I knew, but with a clarity I had rarely seen, all through the medium of Sinclair’s long, futile, footsore expedition. It crackled with energy, metaphors going off like fireworks. How perfect to call the Dome ‘a blob of congealed correction fluid, a flick of Tipp-Ex to revise the mistakes of 19th-century industrialists’. It fitted well into a genre of experiential writing that I had sought out since my teens: Tom Wolfe, Hunter S Thompson, PJ O’Rourke’s Holidays in Hell (1988), William Gibson’s unmatched essay about Singapore for Wired, ‘Disneyland with the Death Penalty’ (1993). I wanted to write like that, and Sorry Meniscus showed that you didn’t have to go to Singapore or Las Vegas or Moscow – you could do it on your doorstep, and serve a sharp journalistic purpose along the way.

You read Sinclair, Sebald and Self, and wanted to do the same? Get in line with the others, Mr Original

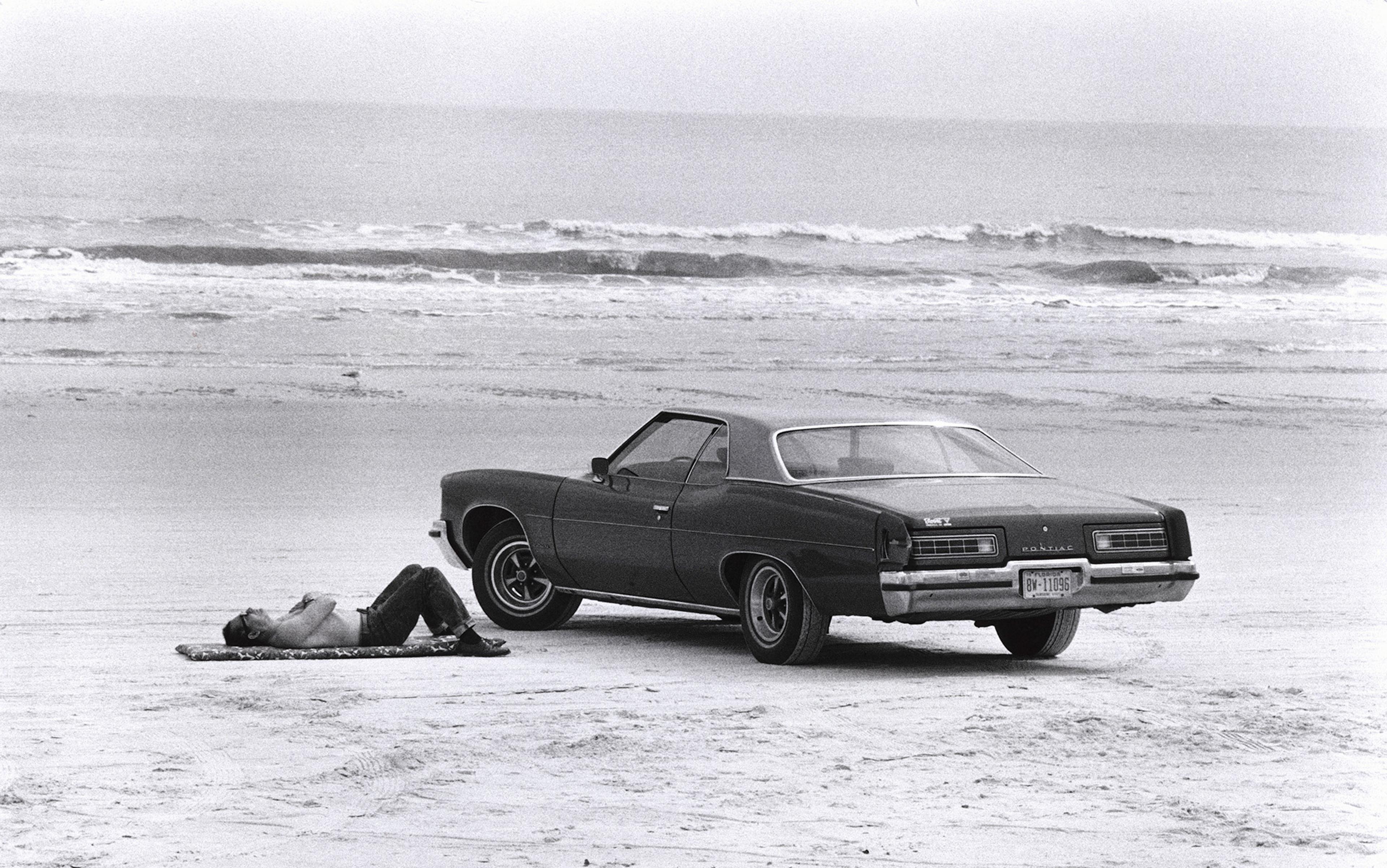

It was a fortuitous time to come across Sinclair. He would, shortly, experience considerable mainstream success with London Orbital (2002), an account of an effort to walk around the M25 motorway that encircles the capital. As psychogeography prospered in the present, I read and watched back into its past, back to Patrick Keiller and Chris Petit’s elegiac films of the early 1990s, to W G Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn (1995), to Jonathan Raban’s celebration of the broken London and New York of the 1970s, and to a number of novelists, notably J G Ballard and Michael Moorcock, whose mystical novel Mother London (1988) I quickly found and devoured.

Meanwhile, walking was being rediscovered as a tool useful to journalists writing about architecture and the city. There’s a similarly long tradition of this, in which the presiding saint of urban studies, Jane Jacobs, plays a prominent role. Her descriptions of pavement life in ‘unslumming’ parts of New York and Boston have become a ubiquitous model. Michael Sorkin’s Twenty Minutes in Manhattan (2009) and Sharon Zukin’s Naked City (2010) are both bound in shoe-leather. On this side of the Atlantic, Will Self, Owen Hatherley and Jonathan Meades have made the go-and-see-for-yourself ethos of Ian Nairn the basis of a new school of urban writing. The descriptive stroll has become a de rigueur part of all urban-architectural critique: Rowan Moore’s book about London, Slow Burn City (2016), opens with a mini perambulation from the zoo to Primrose Hill.

This mode of writing is, indisputably, dominated by white males, with a few hardy exceptions: Sukhdev Sandhu, Laura Oldfield Ford and Lauren Elkin, whose magical book Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice and London (2016) does much valiant work to redress the imbalance. Also, being necessarily introspective and subjective, the genre is equally prone to accusations of pretension. Assuming you are still reading (you are, aren’t you?) you might well have spent the last couple of paragraphs rolling your eyes at the conformist quality of my young non-conformism. Oh, you read Sinclair and it changed your life, did it? You read Sebald and Self’s essays and wanted to do the same? Ballard fan, are we? Get in line with the others, Mr Original. Conscious of all this, while I continued to enjoy reading autobiographical urban criticism, I mostly avoided doing it myself, even as I became an architecture writer. I appreciated my end-of-term assignment, then, as an excuse to freely indulge myself at last in this kind of writing.

Stratford is a place that seems to invite Sinclairian reflection. My starting point was Meridian Square, a busy triangle between the ziggurat steps leading to Westfield, the station, and the older shopping mall, Stratford Centre. It’s an ugly location, overshadowed by glass eruptions of capital (promising ‘Living on a Higher Level’) as well as some of the most offensive public art to be found anywhere, and in 2013 it was named the worst crime hotspot in London. But I come here regularly, and it always seems more successful than anyone would admit. The constant pulse of people – buskers, evangelicals, Londoners lounging on the steps – makes it more than a simple plane of circulation, a leftover shape between station, mall and mega-mall, three grinding glaciers of urban form.

The day of my walk coincided with a strike by junior doctors, and some had gathered at Meridian Square to give passersby lessons in CPR. I stopped and volunteered, figuring that it would be a useful skill to learn, and that such chance interactions were in the spirit of the exercise. For a few minutes, I knelt on the flagstones and massaged the chest of a limbless dummy, before learning how to use a defibrillator machine. I tried to think of ways this diversion could be drawn into the fabric of the exercise, perhaps by drawing parallels with the evangelicals, of revival and life and rebirth, but could not. It was an isolated bubble of urban incident – something that could happen only on the street, but also something that remains there. It was in the spirit of the dérive – ‘between the useful and the gratuitous’, in the words of the writer and critic McKenzie Wark, who I shall return to. But to drag it into the realm of prose and metaphor felt only gratuitous, nothing else.

From that point, I found that a cityscape I regarded as familiar was not what I expected. The land under my feet did not match the land in my head. The interzone between Stratford and Mile End stations, a one-stop half-inch on the Tube map, a flash on the bus, a place I lived in for seven years and know inch by inch, becomes an exhausting 30-minute trek when consumed all at once on foot. And I did not even have the compensation of imagining that I might be doing something original. The stretch from Stratford High Street to Bow Church is Peak Sinclair: the Lea Valley, the Northern Outfall Sewer, a hanging flap of the Olympic Park, roadworks, contaminated land, and bus stops where the buses no longer stop. This is geographic and literary terrain he has returned to time and again.

Only once along the way – in Aldgate – did I feel myself in a realm where description and reflection might have value. There, the city has been thoroughly remade in recent years, with a cluster of silky glass and razor-edge brick towers. The scraping drone of machines boring holes for pilings blended with the dance music from a Vietnamese restaurant and the cry of a busker’s bagpipes into an authentically eerie banshee moan. But even committing these words to screen, I felt, feel, myself following the literary model of others. There were personal – if not unique – associations, of course, from childhood, late-1990s unemployment, and later life in a succession of rented flats. But it had all been pre-filtered through literature. Any value I might have as a witness had been foreclosed by my decades as a reader. This was my depressing conclusion as I passed the Waterstones where I had bought Sorry Meniscus – look, there’s where I purchased some words. Bayswater, Notting Hill and Holland Park – places I know intimately through family – promised more original reflection. But even there I found myself wanting to quote as much as to remember, associate or critique. London’s West is as saturated in psychogeography as the East, by Moorcock and Ballard, Raban and Amis.

What troubled me was more than the fear that my dérive might turn out a little, well, derivative. My meanderings – literal and figurative both – were at odds with the Situationists’ original vision of the thinking-walk: they were not attempting to revive a leisurely past, but confronting a leisurely future. Constant Nieuwenhuys, the Dutch artist who did more than anyone to spell out the urban alternative proposed by Situationism in his utopian megastructural proposals, said in 1960 that Situationist practice had two goals: ‘A transformation of our habits, or rather of our way of life or lifestyle, and, connected with this, a profound change in the way our material environment is produced, a dynamic urbanism.’ The change to the fabric of the city itself is secondary to the change to the individual. He continues:

Life is activity. The freedom won as a result of the disappearance of routine work is a freedom to act. Obviously, it will be creative activity that replaces work.

The disappearance of routine work, described here, was widely assumed to be an inevitable product of automation in industry and the rise of information technology. As is so often the case in the prediction business, this did indeed happen, but not in the expected fashion, and certainly not with the expected results. Fifty years on, routine work has disappeared for hundreds of thousands in the workforce, including for me. I have been a freelance journalist and author for five years, by choice; many thousands of others have had non-routine work inflicted on them, in the form of obligatory zero-hours contracts, or finding the ‘gig economy’ pioneered by Uber and Deliveroo preferable to pursuing non-existent or abusive welfare in an economy where full-time work at a living wage is harder to come by.

Even at the more fortunate end of this scale, I don’t feel particularly free. It had all seemed very appealing, when viewed by my younger self, this strolling and essayism. But it has become a more-or-less ruthless monetisation of creative instincts. Walking from Westfield to Westfield, at one with my thoughts, I found that my thoughts regularly turned to: where might I sell this? And here we are! Work had colonised my creative instinct.

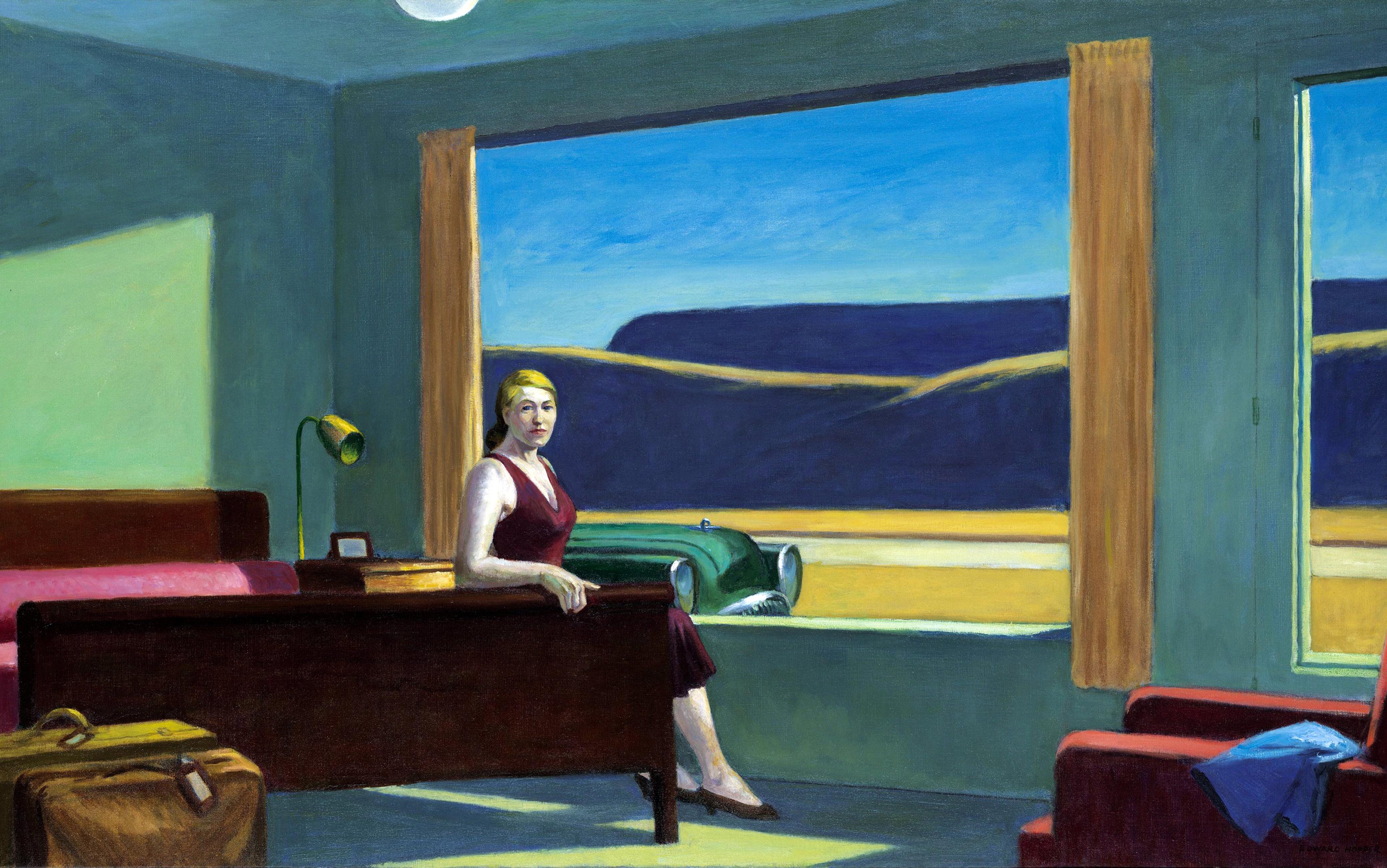

‘Rather than reduce the working hour, avoid it as much as possible,’ writes Wark, paraphrasing Debord, in The Beach Beneath the Street (2011), his luminous history of the Situationists. ‘But if there is no work, then there is no leisure either. … The dérive then becomes the practice of lived time, time not divided and accorded a function in advance; a time inhabited by neither workers nor consumers.’

The crashing of those boundaries between work, culture and leisure has not made my life or practice one glorious subversion, but a slick of low-level creative anxiety, punctuated by eruptions of deadline and financial stress.

The psychogeography of the past 20 years, in its focus on the shortcomings of the urban fabric under capitalism, has led to the neglect of one of the most important aspects of the dérive. Debord, Constant and the others were as much concerned with the regimentation of time and space. It was not just the city that the planners were dividing into strict, functional zones, it was the day, and they were leaving little time for culture.

Wark brings all this into focus:

By wandering about in the space of the city according to their own sense of time, those undertaking a dérive find other uses for space besides the functional. The time of the dérive is no longer divided between productive time and leisure time. It is a time that plays in between the useful and the gratuitous. Leisure time is often called free time, but it is free only in the negative, free from work. But what would it mean to construct a positive freedom within time? That is the challenge of the dérive. … [it is] a new way of being in the world.

Psychogeographical writers have been instrumental in painting an inviting picture of the leisurely writing life, in which the fortunate scribe could step forth from his (generally his) home and weave what he saw around him into words, and those words into gold. This has given way to a wearying reality in which work has seeped into every crack, every excursion must be scanned for pitch possibilities, and one seldom leaves the house anyway. And that seems to have seeped back into the psychogeographical mainstream.

Childcare’s unshiftable commitments feel like a kind of liberation, time when I must be in that time and nothing else

Twenty years after Sorry Meniscus, Sinclair produced his masterpiece, Hackney, That Rose-Red Empire (2009), at last the Hackney book that he had been sallying towards for years. But then, in 2011, in the patchy and confounding Ghost Milk, he developed a tendency for the freelance writer’s back-brain to intrude on the page – there were moans about late payment, grumbles about being interviewed on the Greenway as the voice of London miserablism, arm’s-length corporate hackwork, fretting about what it all adds up to. ‘If you fancy building a mystique, bury your archive,’ he had written in Hackney, That Rose-Red Empire. In Ghost Milk, the mystique cracks amid the quotidian grumbles, and the archive is unburied and sold to the Harry Ransom Center in Texas, the retirement plan of many writers.

‘Life’s chief emotional drama, after the never-ending conflict between desire and reality hostile to that desire, certainly appears to be the sensation of time’s passage,’ Debord wrote in 1957. But time is no longer regimented, and neither is work, not for a growing army of precarious creators in the content industries. It slides by horribly, as technology and precarity have bled work across life.

I wonder if perhaps the dérive was better suited to a world with less appetite for ‘content’ and firmer contractual arrangements? Walking is an aid to thought and will always be an aid to writing – all three happen at the same time. But in London, the dérive has come adrift. A form of writing that I once aspired to has expired. My own new plan is to counter the dreary elision of work across personal space-time with a bit of sanitary zoning. I have two young children, and they come with immutable routines of transport, feeding and bedtime. Far from being onerous, these unshiftable commitments feel like a kind of liberation, the time when I must be in that time and nothing else. I wonder what else can be achieved by setting firm and fixed windows in the day, where the electronic overseers are muted, and a single focus is found?