The year 2023 marks the tercentenary of the birth of the Welsh polymath Richard Price – dissenting minister, mathematician, moral philosopher, and author of influential tracts on the American War of Independence and the French Revolution. Yet he is all but forgotten. This cultural amnesia is all the more striking when you consider that his obituary in 1791 predicted that this so-called ‘Liberty’s Apostle’ would be remembered alongside Thomas Jefferson, Lafayette and George Washington.

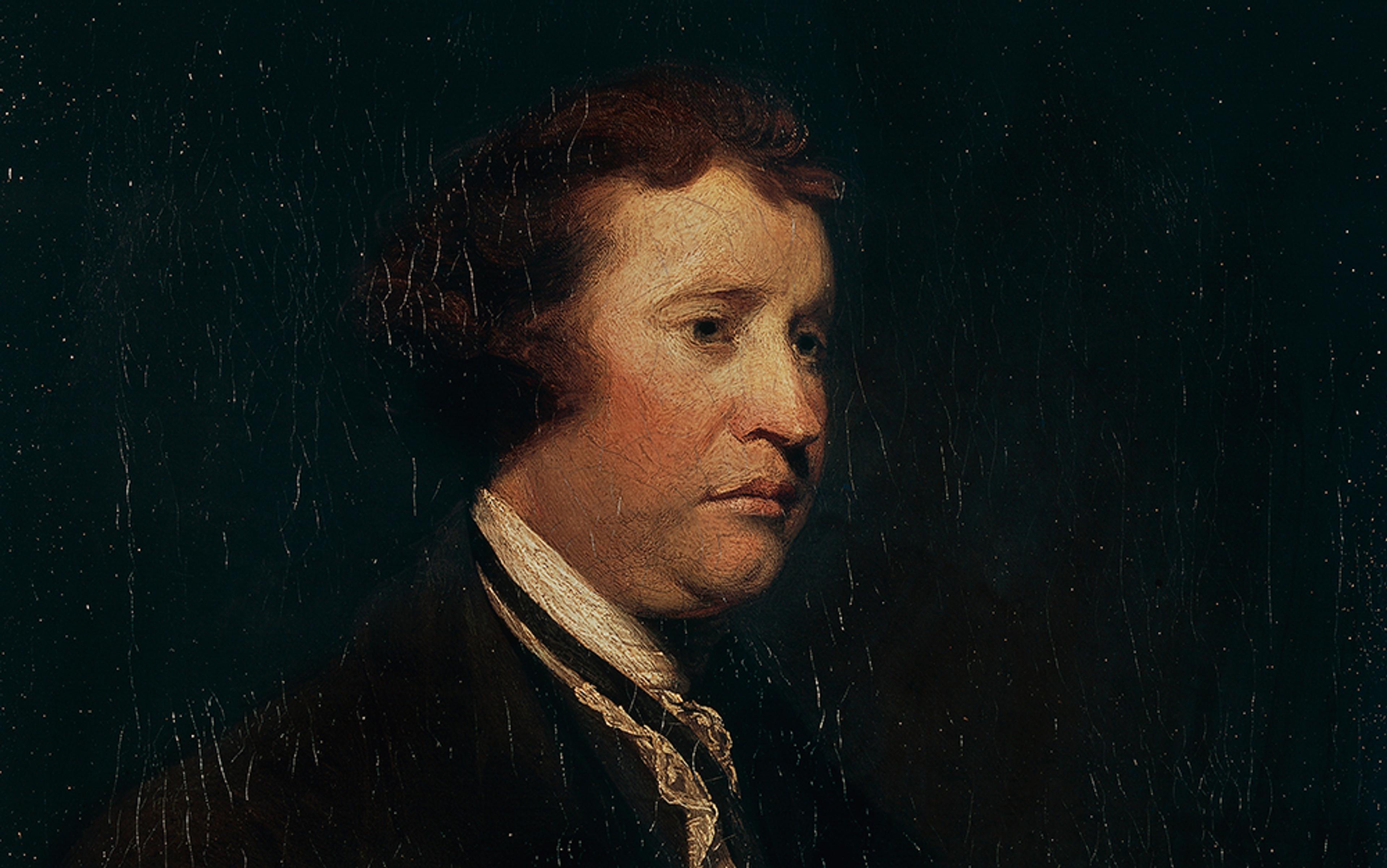

Portrait of Dr Richard Price (1784) by Benjamin West. Courtesy the National Library of Wales

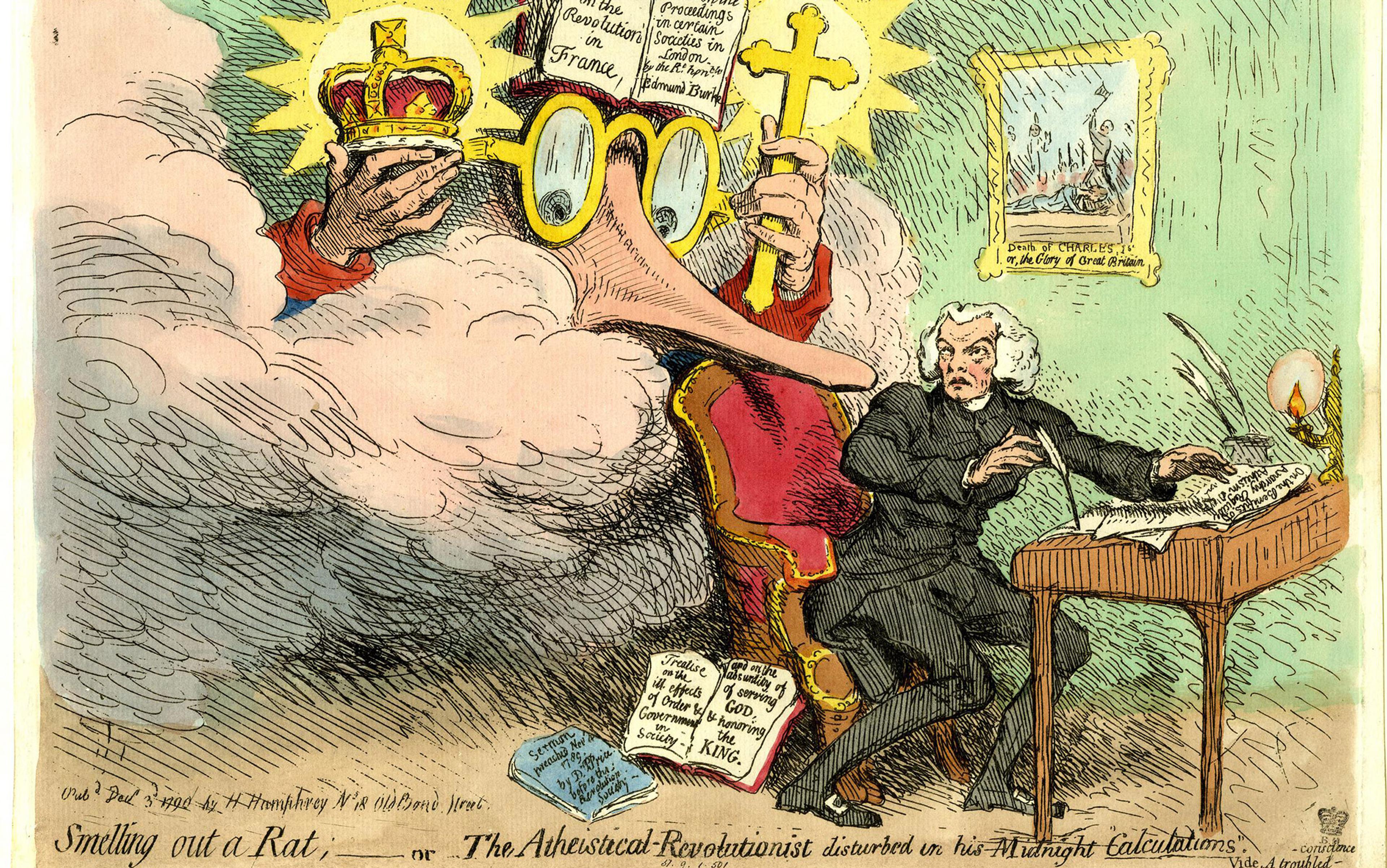

Price may be familiar to those with an interest in the 18th century and English Dissent in particular, and perhaps to those with an interest in the history of moral philosophy of that period, but beyond these circles little is known of someone who, in his lifetime, was held in equal standing with Edmund Burke. Indeed, the fact that Burke felt compelled to respond forcefully to Price’s sermon ‘A Discourse on the Love of Our Country’ (1789) is indicative of his reputation. Contrary to the oft-recited history, it was Price’s text and not Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790) that began the Revolution Controversy, a seminal debate in modern political thought.

In terms of his ethics, Price was notable as a figure who challenged the prevailing moral sentimentalism (the view that our emotions ground our ethical judgments) of those such as Francis Hutcheson and David Hume. Together with his political ideals, which captured much of the radical worldview in the late 18th century, Price’s body of work is representative of a richness in our intellectual heritage that is often overlooked in Britain and beyond – by a mainstream narrative that cleaves to the predominance of empiricism and liberal utilitarianism.

Price, and his remarkable contributions across a range of areas, can be fully appreciated only in light of the religious and social milieu that he occupied, one that is embodied by the term ‘English Dissent’. It reflects both the standing of the Protestant denominations that stood outside the Anglican Church, and their positioning in terms of the reformist agenda that issued from their peripherality, and of which Price would become a leading exponent as a Unitarian minister at Newington Green in north London, where he took up residence in his mid-30s.

Born in 1723, Price was brought up in his native Wales in a dissenting community of a very different kind, at Tynton farm in the Garw Valley (the village of Llangeinor stands there today). His family had close ties with Samuel Jones, who was part of an emerging Puritan movement in Wales during the English Civil War, but who was forced to sequester with the Restoration. With the support of Price’s grandfather and others, Jones was able to establish a meeting house in the Garw Valley that would continue the tradition in the spirit of an orthodox Calvinism that Price himself would come to thoroughly reject. Indeed, this became a familial theological conflict, captured most symbolically in the story of the father, Rhys Price, happening upon his son Richard reading the work of the Anglican cleric Bishop Samuel Clarke, and throwing the offending book into the fire.

Rhys Price in fact removed his son from the Dissenting Academy he attended in Pentwyn, west Wales, because of his concerns about the ideas he was being exposed to by another, more radical non-conformist Samuel Jones. The young Price was sent to Talgarth under the tutelage of the renowned Vavasour Griffiths, but it seems the student’s head had already been turned. When his father died, and his mother soon after, Price saw to it that his sisters were well looked after, and then – as so many Welsh before and after – he followed other members of his family to London to seek, if not his fortune, then a flourishing future in the metropolis. There he was soon fortunate enough to be appointed chaplain for George Streatfield and his family, and became assistant to Samuel Chandler (an important figure in the history of English Dissent) at the Old Jewry Meeting House.

While ‘dissent’ in its earlier form was a term used to designate the whole gamut of Protestant denominations and sects that rejected the authority of the Church in England – from Puritans to Quakers to Levellers – the English, or Rational, Dissenters were a specific group that emerged during the 18th century, and whose core values tended to coalesce around a particular set of ideas and principles that were, in the broadest term, progressive in nature. This was in no small part a reflection of their material situation, marginalised as they were by the Test Acts that effectively rendered them second-class citizens, and that made political reform an obvious priority. Their ideals also emerged from a form of rational religion that aligned their Christian faith and belief with the scientific revolution of the time, rather than with the orthodoxy of the Church of England.

A striking example of this is to be found in the hypothesis that Bayes’s probability theorem (which should perhaps be called ‘Bayes and Price’s theorem’) was inspired in part by a desire to establish mathematical proof for the existence of miracles, in response to Hume’s sceptical arguments in his notorious essay ‘Of Miracles’ (1748). Price was Thomas Bayes’s literary executor, and he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society for his work in amending, expanding and bringing the theorem to light. Bayes’s work in probability has had an immense influence on areas involving statistical inference, including in the development of the internet and of artificial intelligence.

It was in this dissenting milieu that Price found himself at home and began to exert influence. He became a focal point for the dissenting community when he took up his role as minister in the Newington Green Meeting House. By that time, both Streatfield and Price’s uncle, who had welcomed his nephew to London, had died. So Price was making his way as an independent man in the world, having married Sarah Blundell, who was, somewhat surprisingly, a lifelong member of the Anglican Church. Also during this time, Price’s defining work in ethics, A Review of the Principal Questions in Morals (1757), was published.

Wollstonecraft had a great affection for Price who had taken her under his wing and promoted her cause

A further defining relationship for him was with Joseph Priestley, another of the key figures in the dissenting movement. The Welsh historian Iwan Rhys Morus has recently discussed Price and Priestley in the context of their ties with another important contemporary, Benjamin Franklin. Morus elucidates how the three sought to bring science into the service of their wider dissenting agenda, and interestingly struck upon the theme of the three as thinkers from the periphery who brought innovation, if not revolution, from their respective origins beyond the imperial capital. Morus explains how this disrupts typical assumptions about the flow of knowledge from the metropolitan core.

.jpg?width=3840&quality=75&format=auto)

Mary Wollstonecraft (c1797) by John Opie. Courtesy Wikipedia

The idea of science deployed in the service of a progressive political agenda reflects a wider culture that had a broader impact on contemporary culture, as well as an appeal beyond its context of religious dissent. We can see this in the way that Mary Wollstonecraft, who was not herself a dissenter, made connections with key figures in the movement and found an affinity in their manners, their progressive ideas and their treatment of women. At Newington Green, she established her school for girls and began to develop her social critique that would eventually find expression in the Revolution Controversy and her book A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). Before that publication, however, came A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790), which was in part a defence of Price against Burke’s attacks, though it is usually portrayed as solely directed at Burke. Wollstonecraft had a great affection for Price who had taken her under his wing and promoted her cause both financially and practically by introducing her to the publisher Joseph Johnson.

Despite Price’s secular influence, it is important not to lose sight of his religious core, not only because it informed his ideas in politics and ethics, but also because of the way in which it inspired his relentless activity. In particular, his tireless work in the field of insurance – he worked as an actuary, and published important papers on the mathematics of life assurance and annuities – is an example of how his concern for the welfare of others was driven by his religiosity.

Given Price’s deep Christian faith and his religious values, the ethical perspective conveyed in his Principal Questions is somewhat unexpected. Price rejects the idea that what is good issues directly from God’s will, and instead develops what the Welsh philosopher Walford Gealy regarded as an early version of the ‘autonomy of ethics’ associated with the influential 20th-century philosopher G E Moore. Broadly speaking, this is the idea that there exists a self-sustaining moral order that informs what is good or bad, independent of God or nature. This makes Price’s ethical outlook closer to his rationalist contemporaries from the Continent than to that of the British empiricists, for he argued that we are able to perceive the moral quality of any action on the basis of our understanding. That is to say, the mind is an independent source of knowledge: we are endowed with a moral understanding that allows us to perceive directly the moral quality of human action. The empiricists, broadly speaking, regarded good and bad as secondary qualities that do not signify anything in the objects themselves, but rather their effects upon us, particularly their emotional affects. In contrast, Price adopted a form of moral objectivism, believing that the moral quality resides in the action itself and that we perceive this through use of our understanding.

Price’s moral philosophy can be seen as a critical response to the sentimentalism of empiricists such as Hume and Hutcheson. As far as Price was concerned, their approach, which foregrounded emotional reactions, rendered morality a subjective and psychological matter, subject to individual whim, whereas Price believed that moral judgments occupied the same realm as mathematical truths, and are universal, permanent and unconditional. In this way, the good is not a quality that can be accounted for or described in relation to, or through reference to, other objects or perceivers.

Price’s politics are built on his ethics with an emphasis on freedom, virtue and knowledge

The emphasis here on our innate ability to perceive the good in and for itself anticipates not only Moore but the moral intuitionists of the 20th century such as the Scottish philosopher W D Ross. It, in some ways, also anticipated aspects of Immanuel Kant’s philosophy, in particular his argument that moral duties arise directly from our ability to perceive the good and the bad.

The comparison with Kant is interesting and intriguing. He and Price were contemporaries born only a year apart, and similarities in their moral perspectives – particularly their rejection of consequentialist and utilitarian approaches – are striking. While Price never came close to Kant’s detailed and painstaking treatment of the various aspects of philosophy – he was too busy involving himself in the practical debates and activities of the day – his political tracts are his best known, and provide the outlines of a republican cosmopolitanism that is in line with the cosmopolitanism that Kant developed. In Kantian fashion (to put it anachronistically), Price’s politics are built on his ethics with an emphasis on freedom, virtue and knowledge.

In Price’s pamphlets, which supported the American War of Independence and the revolution in France (he died in 1791 before the outbreak of the Terror), a radical republican view emerges. The best known of these is ‘A Discourse on the Love of Our Country’ (1789), published at the outbreak of the French Revolution. In it, Price expresses support for the revolution on the grounds that it represents the spirit of England’s Glorious Revolution of 1688, when James II was deposed and replaced by William of Orange. Price’s sermon was also a mature statement of the most important aspects of his political philosophy, presenting arguments and themes that still resonate today.

The first of those, one that often goes unrecognised, is that Price arguably provided one of the earliest statements of civic nationalism, in declaring that by ‘our country’ we mean ‘that body of companions and friends and kindred who are associated with us under the same constitution of government, protected by the same laws, and bound together by the same civil polity.’ As a member of a community marginalised by the Test Acts, and as a Welshman, and very likely Welsh-speaking, hailing from the Celtic fringe, Price articulated a capacious idea of nationality that could offer a fuller sense of membership for those outside the established elite. His ideal of civic nationalism was part of a wider set of ideas around nationalism that embodied two key principles: first, that love for our country should not mean that we regard ourselves as superior to others; and, secondly, that all nation states should conduct themselves in the spirit of cooperation and not competition. Nationalism can be valid and legitimate only when it is held in check by reason and by sympathy for our fellow human beings.

It’s striking how sceptical Price was about the effects of power on those who possess it

These admirable principles lay the basis for Price’s cosmopolitanism. He was among those Enlightenment thinkers who believed in a peaceful worldwide federation, a model for which in his view was offered by the new emerging federation in America. Price’s belief in virtue and freedom as the basis for politics would also lead him to advocate for the abolition of slavery and hold the Americans to account on these matters.

The republicanism of Price is another defining aspect of his politics, and as the political scientist Nicole Whalen recently argued, this laid the basis for a proto-anticapitalism that advocated a distributive equality in contrast with the sort of society envisaged by Adam Smith. Moreover, what is particularly striking is how sceptical Price was about the effects of power on those who possess it, calling to mind the basic anarchist critique – that power corrupts. Connected with this, Price emphasises that we as citizens must be active and not passive, and that it is our duty to challenge our leaders and to hold them to account. This is not only because that is the only way to ensure good governance, but also because this kind of participation in our community is what it means to be human. We are social beings. It is both our privilege and our duty as humans to contribute in this way.

Despite his move to London, Price never lost his Welshness. He was a religiously driven nonconformist with energy and intelligence of a type that would come to dominate his homeland, and lay the political basis for what is often referred to as the ‘rebirth of a nation’ in the latter half of the 19th century. In the wider context of the United Kingdom, however, the dissent Price embodied would remain just that – an intellectual and political spirit that was a counterpoint to a dominant culture entrenched in privilege and conservatism. The British establishment worked hard to demonise and marginalise Price and his form of politics in his lifetime. The widespread ignorance today of Price both as a thinker and as a public intellectual is a mark of their success.