The transformation of American public opinion on same-sex marriage is among the most remarkable and rapid shifts in moral consciousness ever recorded. Since the late 1980s, public approval of the practice climbed from 11 per cent to 70 per cent, where it has remained stable since 2021. What explains this?

This is in part a puzzle about democracy. On its face, democracy offers the promise of voice and foment, of revolution without war. And liberal democracies have indeed propelled just about every major social advance over the past 100 years or so: not only gay rights, but also labour rights, women’s rights, animal welfare, environmentalism and racial equality. The latter notably encompasses the dismantling of formalised racial segregation in the United States, another stunning (if highly imperfect) turn in moral history. Democracy isn’t the only factor that explains all this, but it is hard to tell a story about social progress in which it doesn’t play a key role. At the same time, recent events confirm what a large body of research has long established: democratic publics are largely ignorant and irrational, approaching politics in roughly the same spirit as bare-chested soccer fans contesting a foul. Most of us – and particularly those of us with broadly liberal intuitions – carry around these dissonant ideas together: democracy is an open invitation to the ignorant and, at the same time, a vital instrument of social progress.

Social history can help us make better sense of these intuitions. The case of same-sex marriage, in particular, provides an astonishing example of social progress at scale, propelled by democracy, among a public full of spite and misinformation. Here, democracy’s special virtue was its ability to convert minority grievances into ‘experiments in living’: interventions in social life that gradually reshape core social emotions and identities. That, in turn, enables people to respond to the grievances of groups otherwise marginalised under systemic oppression. Democracy thus drives social progress by improving the background conditions of moral cognition.

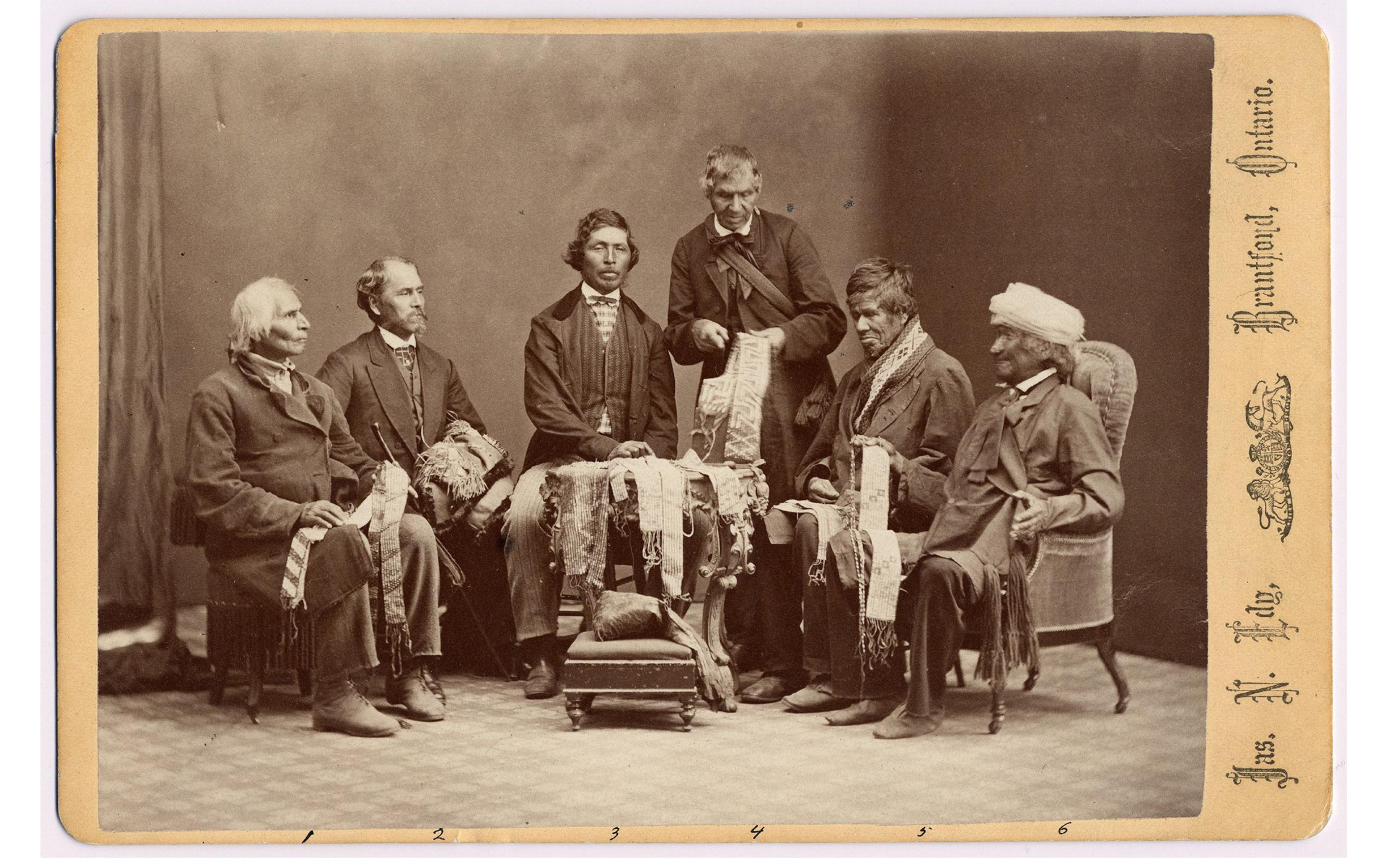

The American gay rights movement first began to take form in the 1950s, when hostility to homosexuality was the default, and a suffocating body of laws and norms forced homosexuals into a life of fear and repression. The earliest gay rights organisations in the US, such as the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis, grew out of homosexuals’ increasing frustration with the status quo and, relatedly, a coalescing sense of homosexual identity itself. The earliest arguments for gay rights centred on the premise of basic equality, and drew on parallels with the movement for racial equality that was taking shape. Through the 1960s and ’70s, the movement grew into a larger and more vocal social force, achieving a progressive series of important cultural and legal changes: the formal revocation of the government’s ban on homosexual employees, the election of the first homosexual representative to the Massachusetts state legislature, and dozens of ordinances barring anti-gay discrimination at the county and municipal level.

The AIDS crisis of the 1980s brought greater attention to the movement and catalysed highly effective activism, and this is when public support for gay rights first begins to tick upward. The 2000s saw continued advances as sympathetic portrayals of homosexuality spread more widely through the culture. Hate-crime protections were extended to homosexuals, anti-sodomy laws were struck down, and same-sex marriage was legalised for the first time in several American states. In 2015, the push for same-sex marriage culminated with the landmark Obergefell v Hodges Supreme Court decision, which secured the right to same-sex marriage as a matter of US federal law. Remarkably, in spite of the Donald Trump administration’s reactionary push against transgender rights, there has been no widespread movement to walk back same-sex marriage rights.

The dominant theoretical accounts of democracy don’t offer a good model of this trajectory. Going back (at least) to the fourth US president James Madison, the traditional liberal account of democracy focuses on the idea that, by distributing power widely, it is difficult for any one group to dominate. Beyond the reduction of domination, this thinking goes, power-sharing also tends to encourage compromise as smaller factions seek coalitions to gain power. But the same-sex marriage case illustrates the limitations of this model. Sometimes the logic of power-sharing favours minority groups, particularly when they provide a ‘tipping point’ vote. But often – as in the case of midcentury homosexuals or African Americans – it entails structural marginalisation from power. Majorities thereby become tyrannies, systematically ignoring the concerns of groups perceived to be unnecessary or harmful to the winning coalition.

The single most important social change was the (open) social presence of homosexuals themselves

In part because of this concern, ‘deliberative democracy’ has been the more influential model for contemporary theorists. This approach envisions democracy, in the ideal, as an inclusive conversation among equals, in which decision-making proceeds based on ‘the unforced force of the better argument’, as Jürgen Habermas put it, rather than power alone. Here, democracy aspires to an ideal in which the arguments of all are heard and guide the public use of power. Political decisions thereby show respect for the will of everyone (even minorities) and resort to coercion only as a necessary fallback.

As the same-sex marriage case reveals, however, democracy functions through a variety of mechanisms that don’t easily fit the model of ‘deliberation’: voting, protesting, activism, the arts and so on. This wider spectrum of cultural factors influences moral reasoning, not directly, but instead by reshaping the psychological background of emotions and identities against which reasoning takes place. A large body of social psychology confirms that our attitudes towards other social groups are guided by our tendencies toward in/out-group sorting and, relatedly, a repertoire of identity-linked emotions that determine how we respond to their concerns. The same-sex marriage case nicely illustrates the fact that, if we want to understand changes of moral mind, we need to attend to this wider psychological context as it shifted over a period of decades.

The single most important social change wrought by the gay rights movement was the (open) social presence of homosexuals themselves, both in mass culture and in day-to-day personal interactions. The first step occurred in the 1960s and ’70s, as homosexuals gradually made the shift from invisibly to visibly oppressed. Several openly gay candidates ran for local public office, and a number of major protest events – such as the landmark Stonewall uprising in New York in 1969 – drew media coverage and wide public attention. Popular films and fiction, such as James Baldwin’s Another Country (1962), began to bring homosexual characters and their interior lives into public view. The AIDS crisis of the 1980s provided a turning point, when images of the sick, dying and grieving helped to transform homosexuals from an imagined radical fringe to real human beings with relatable vulnerabilities. The AIDS crisis also organised a highly visible and effective activist campaign by groups such as ACT UP. That, in turn, helped inspire increasing numbers of homosexuals to come out of the closet, a trend that continued steadily upwards for decades. In the mid-1980s, polls show that only 5-20 per cent of Americans had a personal acquaintance who they knew to be gay. By the end of the 2000s, that number was about 70 per cent. Survey research confirms that the single most important factor in causing people to change their mind about same-sex marriage was personal contact.

This rise in personal contact was matched by increasingly sympathetic exposure to homosexuality through mass media. Through the 1990s and 2000s, network television showed growing numbers of sympathetic and/or normalised gay characters. By 2010, the network sitcom Modern Family, whose main characters included a gay couple with an adopted child, was among Republicans’ most popular shows. In 1994, IKEA ran a television ad featuring two men buying a dining table together, marking a new and normalising acceptance of homosexuality among the corporate mainstream. This trend was matched among elites, as increasing numbers of gay politicians and celebrities made their identity known. By the time Pete Buttigieg ran for US president in 2020, his sexuality attracted little attention in major press outlets.

Overall, we can observe a virtuous feedback loop here: social progress arises through interventions in social norms that, over time, transform the emotions and identities that govern the reception of moral arguments. In turn, this sets the stage for further interventions in practice, which further transforms social experience, which further reshapes the evaluation of arguments for equality, and so forth. The process begins with a small vanguard of the exceptionally prescient and courageous, who are willing to voice their grievances, or their support, at great personal risk. As greater numbers add their voice, the costs of joining the movement decline, and previously radical ideas gradually take on a more moderate valence.

The key ingredient in this story is the role of lived experience in moral cognition. This idea was central to the political thought of the American philosopher John Dewey. In The Public and Its Problems (1927), Dewey argued that we should think of democracy not just as a framework for decision-making or deliberation but as a way of life centred on a particular ideal of community:

Wherever there is conjoint activity whose consequences are appreciated as good by all singular persons who take part in it, and where the realisation of the good is such as to effect an energetic desire and effort to sustain it in being just because it is a good shared by all, there is in so far a community. The clear consciousness of a communal life, in all its implications, constitutes the idea of democracy.

Dewey’s key insight was that a democratic public needed, not just an intellectual endorsement of shared principles or formal institutional equality, but a sense of common good and an ‘energetic desire’ to sustain it. That depended on the development of pro-social ‘habits’ – routine patterns of thought often embedded beneath conscious reflection – that would activate genuine care and concern across social differences. And this, in turn, required the cumulative impact of our day-to-day experience – our way of life – encountering diverse social groups.

Gay voices were often unwelcome but they became increasingly difficult to dismiss

When minorities experience profound frustrations that do not arouse the ‘desire and effort’ of others, societies need to experiment with new ways of living together in order to deepen the reservoir of community. Because there are always new problems and frustrations down the road, Dewey argued that democracy itself required continual experimentation. In the mid-20th century, the systematic marginalisation of homosexuals made it impossible for the average American to generate the kind of sympathy and identification required to address oppression. The gay rights movement effected an intervention in social life that enabled Americans to develop new habits of moral cognition, thereby repairing (though still imperfectly) the democratic community. We learned from an experiment in living: the experience of acting on a novel ideal.

How exactly should we think about the role of democracy in all this? The definitive feature of democracy is its radical egalitarianism about power. In particular, democracy involves the (nearly) universal distribution of fundamental decision-making powers without regard to merit. That architecture means that the authority for political power lies with all those subject to it (‘the people’) and should serve ‘the people’ considered as equals. Egalitarian elections are the most readily identifiable marker of the democratic approach, and this is perhaps why empirical research on democracy so often centres on the inputs, outputs and procedures of elections. But the formal distribution of basic electoral and civil rights is insufficient.

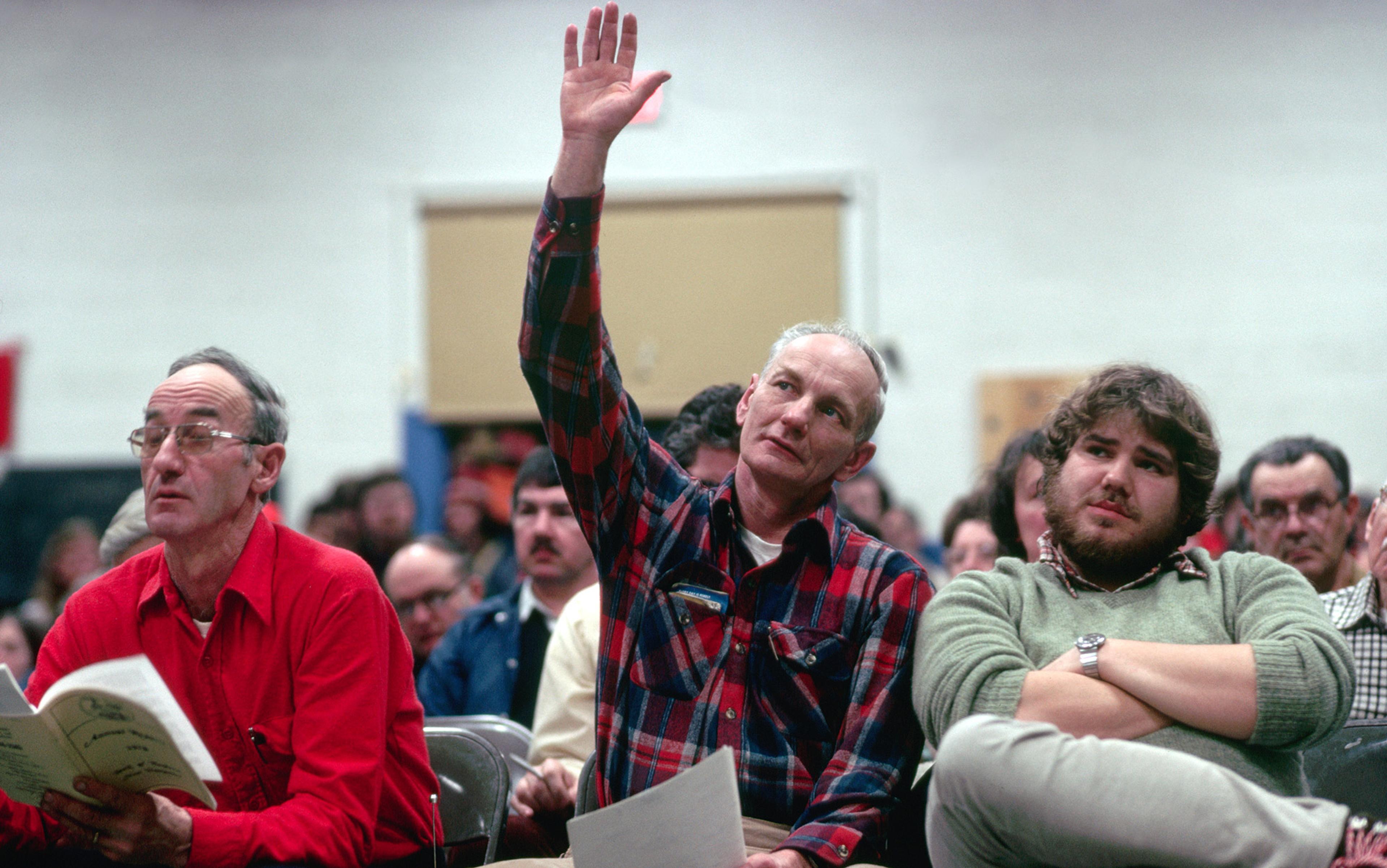

Democracy thus depends on a wider range of norms and institutions. One of these is a wider presumption against hierarchy as a justification for public action and, likewise, the idea that the spaces in which the use of power is being debated, decided and framed should be open and inclusive. A second and related norm is the presumption in favour of open and reasoned deliberative processes, which provide a critical check on existing hierarchies. The battle for gay rights was fought in the public square, in newspaper columns, in scholarly societies, arts institutions and town halls. Gay voices were often unwelcome but, without a principled basis for excluding them, they became increasingly difficult to dismiss. One notable example was the debate about homosexuality within the American Psychiatric Association. In the early 1970s, gay psychiatrists joined activists to argue for removing homosexuality from the profession’s list of disorders. Many dismissed this out of hand, but the opponents struggled to rationalise the existing state of affairs without resorting to brute dogma. The debate spilled over into a series of exchanges in The New York Times, where the old guard was forced into increasingly awkward contortions. Though it was succeeded by ‘sexual orientation disturbance [homosexuality]’, the term itself as a disorder was dropped from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (the profession’s official handbook) in 1974, a key turning point in the cultural change underway. Dogma gradually sank under the combined weight of open public scrutiny and the presumptive obligation to defend power with reasons.

For the liberal, the appeal of egalitarianism is so deeply ingrained that it can be easy at times to forget its costs. In settings where expertise is important, difficult to acquire and relatively straightforward to identify, there are considerable advantages to hierarchy. The community of policy researchers – economists, political scientists, ecologists, urban planners and so on – is to some degree internally democratic. But the threshold for joining this community is extremely high and, without the requisite credentials, there is no prospect of participating in the conversation. The policy world is an elitist institution. This is a highly effective strategy so long as (a) insight is highly unlikely from those without expertise and (b) the typical markers of expertise – a PhD and publications in the subject – are reliable and easy to identify. Meanwhile, the inefficiency of radical egalitarianism – welcoming everyone into the conversation without regard for any markers of expertise – would be enormously costly.

Conditions (a) and (b) are reasonable assumptions so long as we stick to technical scientific matters. But morality is epistemologically different. Two things stand out in this respect. The first is that, historically, the individuals and groups who have offered the greatest moral insights have been distributed unpredictably across social categories. This makes sense given that our moral outlook is to a large degree shaped by the particularities of our identity and experience. Since moral problems are complex and heterogeneous, moral insights emerge across diverse social strata, and typically only in partial, imperfect ways. Immanuel Kant was a white man who authored both the foundational ideas of modern liberty and equality, and, at the same time, some of the earliest ideas in scientific racism. Margaret Sanger was a pioneering feminist voice but also, at the same time, harboured crude inclinations towards eugenics.

The second factor that makes morality epistemologically distinct is that there are no reliable credentials available. If there were PhDs in moral insight, then its wide and unpredictable distribution would be a surmountable problem. But there is no recognisable form of training, education or experience that reliably marks those with most moral insight. So moral insight is both (i) widely distributed across the public in a way that (ii) is not linked to any reliable marker of its presence. These two factors reveal the special advantages of democracy. Under such circumstances, any practices we might use to filter contributions to public discourse would run too-great a risk of excluding critical insights. That risk is further heightened by what a number of philosophers have called the ‘epistemology of ignorance’: the perception of credibility on morality and other matters tends to favour the interests of the dominant group, thereby laundering oppression through the operation of ‘reason’. Under such conditions, we are therefore stuck with the inefficient logic of radical egalitarianism: wilfully ignore presuppositions about merit and hand out decision-making power indiscriminately.

Democracy may have brought us same-sex marriage, but it also brought us Trump

If we rewind to the oppressive environment in which the gay rights movement arose, it is easy to appreciate the importance of democracy’s radical egalitarianism. Social power was tightly consolidated among a white male elite that was thoroughly hostile to homosexuality, and the concept of moral merit was, indeed, explicitly framed so as to exclude homosexuals. In a peculiar synthesis of bogeymen, the idea of homosexuality as a psychological ‘perversion’ was often closely associated with communism. In the McCarthyite fever of the 1950s, homosexuals in the government were seen as ‘moral weaklings’ whose sexual identity made them ‘easy prey for blackmail’ by anti-American elements. Democratic norms and institutions thus could not prevent the marginalisation of homosexuals’ pleas in the national debate. But they did provide enough of an opening to effectively press for social changes that accumulated over time.

The success of the gay rights movement depended on a public deliberative culture that would enable its arguments to be heard and received, both on a small scale (within particular businesses and institutions) and by a wider public. It depended on a series of electoral victories. It depended on ballot initiatives across multiple jurisdictions. It depended on the power of radical protest and civil disobedience, both of which gain their force, not only from formal rights guarantees, but also from the implicit threat of electoral consequences for officials sitting ‘on the wrong side of history’. And it depended on a variety of court battles that culminated with the landmark Obergefell Supreme Court ruling. Though the US Supreme Court itself is a highly elitist institution, the Obergefell decision was made possible only by a decades-long democratic transformation in which arguments for gay rights could be heard, taken seriously, and ultimately enacted without public revolt.

So there is a close link between the virtue of experiments in living, and the radically egalitarian architecture of democracy. Experiments in living play a necessary role in transforming our moral sensibilities so that we are able to respond to the moral concerns of a diverse public. But this requires a social technology that gives voice to the most aggrieved, and gives them a basis for making interventions in social practices. Democracy is that technology. It sacrifices the efficiency of a more merit-based system in order to maximise the odds that, over time, the complaints of the most aggrieved may get some traction.

The sense of doom that many of us feel right now reflects the unpredictable consequences of a system that refuses to gatekeep decision power. Democracy may have brought us same-sex marriage, but it also brought us Trump. Democracy is a vital source of progress, yes, but also, as Plato observed, a potential amplifier of division and ignorance. There can be no purely philosophical solution to authoritarian populism. But philosophy can help us to diagnose our current predicament. The lesson of the history of same-sex marriage is not that democracy somehow makes progress inevitable but, instead, to illustrate how it is that democracy might help us to protect and promote it. We are living through a moment when Americans seem particularly incomprehensible to one another, when our capacity for sympathy, empathy, mutual care and a sense of common fate across social differences is depleted. The path forward requires understanding that this is not a narrow problem that can be repaired through policymaking or education. It requires interventions in social life that allow us to experience one another’s concerns in a new light.